“Where’s the ‘tall’ one?” Using the corresponding gesture for “tall,” Mariam waits for her classmate’s response.

“The ‘tall one’ is in her office. ‘Eye’ is also there,” replies her classmate with a hand gesture and escorts us to the right door.

Almost all the children in this special school for those with hearing loss* have sign names. In this unique language, each word has its own gesture, and normally each name must be signed letter by letter. In order not to have to spell out the names of those close to them each time, those who communicate using sign language, give them specific sign names, so they can point out who they are talking about with a single gesture. The “tall one” for example is the deputy head of the school, Nvard Tananyan, and “Eye” is Gevorg, a former pupil.

In 2020, a kindergarten for children with hearing loss was opened in a separate building within the school campus; however, as refugee families from Artsakh are currently being accommodated here, the six pupils from the kindergarten have been moved to one of the large rooms in the expansive school. The kindergarteners are day pupils unlike the school age pupils who only go home on weekends. Most of the children with hearing loss used to frequent various rehabilitation centers instead of going to kindergarten, or just stayed at home until they were six years old and could start Grade 1 at the school. Now, they have the opportunity to get a headstart at the special kindergarten.

“Knock-knock. May I?” Nvard Tananyan knocks on the door and points out that the children are taking their mid-day nap, and we will have to be patient. “Just look at what my angels are drawing.”

Alen, 5, shows us a number one, which he has painted with the help of his special education teacher, Gohar. He waits eagerly for a compliment, which quickly follows.

Sounds and Rhythm

“The children are not fluent in sign language yet because the study of the language is planned for later, according to the curriculum,” clarifies the educator. “They attend rhythmic classes where they learn to listen and respond to sounds.”

Alen, holding his friend’s hand, takes us to the rhythmics room where the teacher, Anahit Andryan, has already started the exercise. The room is filled with loud music and dance movements. However, Andryan explains that she is not a dance teacher, but a rhythmics teacher.

“We perform general developmental movements, study sonic rhythmics, do hearing exercises,” Andryan says. “Children with hearing loss can perceive sound through vibrations they feel through the floor. We merely help them to develop and strengthen that. Tigran, come. I will beat the drum and you try to copy me.” The teacher begins the exercise and clarifies that hearing issues are not an impediment to understanding rhythm.

“Turn around so you do not see what I am doing. Ready…” The teacher beats the drum and waits for the pupil’s response.

Tigran copies the teacher perfectly.

Andryan says that they also have children who have partial hearing, yet they cannot copy rhythms they hear with the same accuracy. It depends on the individual as the perception of rhythm is not linked to hearing issues.

It is time for Armenian Language in one of the classrooms. Vanuhi, who has partial hearing, is reading Hamo Sahyan: “After all, how can I get up and go? After all, how can I stay somewhere else?”

The English Language and Literature teacher, Anna Poghosyan, notes that the students have problems with the written word as there are no auxiliary verbs, conjugations, grammatical person or number in sign language grammar. For example, in Armenian “I am staying home,” in sign language is expressed as “I… to stay… home.”

Sign language expert Gohar Melikyan says that you don’t need to be hearing impaired to learn sign language, it is like learning any foreign language. She points out that, although education institutions specialized in the study of sign language for those with normal hearing do not exist in Armenia as yet, this practice has been established in various countries around the world for a long time now.

“Sign language consists of hand gestures, lip-reading, facial expression and fingerspelling,” explains Melikyan. “It does not have specific grammar and is simpler than the spoken word. For example, there are no auxiliary verbs, cases, suffixes and so on in sign language. Consequently, it is very difficult for the deaf to write, as they do not have [these concepts] in their [in-person] language.”

Melikyan says that deaf people face difficulties when moving from sign language to the written word and must rely on rote memory, as opposed to those who are able to hear and whose linguistic thought and written word are balanced with each other.

The Armenian language teacher asserts the same, and notes that it is not easy to think in one language, and write in another.

“Varduhi, who has partial hearing – you saw how she was reading Sahyan – has no difficulty in transitioning from sign language to written language, while we still have a lot of work to do with the others,” she says. “This is an issue, not only in Armenia, but also in Russia. We have a pupil now who has come to us from there and, once again, there is the problem of transitioning from sign language to written language.”

Adapting the Curriculum

The teaching staff at the special school all agree that the curriculum – which is approved by the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport – needs to be changed, but for years they have been told by the ministry that it is not possible to deviate from the curriculum. Of course, the methodology and approaches are different, and have been adapted for children with hearing loss, but the curriculum remains the same.

“There are subjects which are not crucial for them. They will not give them anything. But we touch on them because it is required,” says Poghosyan, displaying the blackboard. “See, I am now trying to explain the complex subordinate clause, which, in my opinion, is of no use to them; however, we study complex subordinate clauses for the whole of the ninth academic year.”

“The children’s spelling is faultless because they perceive words using visual memory. They see it written this way, so they never forget.” she adds.

The teacher also notes that the children can study and analyze the works of Armenian authors with great love and skill, but here again they face the same problem – although the youngster can complete the task brilliantly in sign language, difficulties once again arise in writing.

“Sign language helps whatever subject you are explaining, because you cannot do without it,” says Poghosyan. “Signs, the movement of the lips, and facial expressions – all of these complement each other. However, the curriculum is difficult, and we find ourselves in the same place. Our activities must be interconnected – family, school and individual teacher. Only through the joint efforts of these three groups can we expect to raise the level of Armenian language.”

The educational complex, which has a dormitory and buildings for classes, is quite expansive. Tananyan knows every nook and cranny like the back of her hand. In this unique school where hands speak louder than words, there are clubs for carpet-making, shoemaking, sewing and design, sports, mime and so on. Photographs of former pupils who have had athletic success hang on a wall of fame; the years of work poured into such victories by the school community makes them collective accomplishments.

The Hearing Room

There are many classrooms that pique the interest of visitors who step into the school for the first time, the hearing room for example. I was standing in front of it, trying to guess what they taught in that classroom, when Mrs. Tananyan came to enlighten me: “This room is one of the most important classrooms in the school. Individual developmental pedagogical teaching is carried out here. Pupils from preschool to ninth grade try to comprehend the environment, differentiate sounds and so on through hearing exercises. This is the only room where gestures are not used.”

Tananyan has a lesson with the eleventh graders. “Eye” is also there. As a former pupil of the school, he is completely at home entertaining the pupils. He also teaches mime in this classroom. He initially got accepted into the pantomime program at the Yerevan State Institute of Theater and Cinematography. Then, wanting to combine study and work, he transferred to the Department of Directing at Yerevan State Pedagogical University. While the eleventh graders were getting used to my presence, Gevorg (although his sign name is “Eye”, I would definitely have called him “Chatterbox”) told me about himself.

“I was travelling to Ukraine, and there was no translator at Yerevan airport who could help me understand when my flight was, where I should go, or what questions the airport staff were asking,” Gevorg recalls. “As soon as I arrived in Ukraine, they provided me with a translator at the airport and, since I know international sign language, we had no problems communicating.”

Gevorg says that the issues at the airport are the least of his problems. People with hearing loss come across obstacles everywhere: in banks, hospitals, entertainment centers and shops.

“You go to the polyclinic and don’t know how to explain anything. If everyone at home is deaf, who should accompany me to explain what I want?” asks Gevorg. “No medical establishment provides deaf translators. The deaf person must pay whoever is accompanying them, and we frequently ask our teachers to explain to the doctors what we are feeling, where we ache and what we need, via video calls.”

Each of the eleventh graders has their own dream. Mary wants to become an accountant; and George a dress designer. Over the summer, Davit realized his long-held dream and visited the Ministry of Emergency Situations, getting to know the ministry’s work. Mariam is obsessed with pantomime and wants to learn to play the guitar. Sevak, who is from Artsakh, hopes to become an agriculturalist. But they are aware that the journey will not be smooth.

“We go to the bank and only with great difficulty manage to explain that we want a bank card,” remarks George.

“We have no difficulties in cafes. There, we can point to what we want on the menu. They try to help politely; but, for example, problems arise at the polyclinic,” Mariam adds.

Gevorg, as a man who has passed through the tribulations of university, advises his younger friends and pupils. He tells them not to get discouraged when communicating with those who hear. It was not easy for him at first either, when he was studying at the Yerevan State Institute of Theater and Cinematography. He thought that he would never be able to communicate with friends.

“The hearers drew me into their environment. My peers took the initiative and spared no effort in making sure that hearing would not become an obstacle or wall between us,” says Gevorg and professes that he quickly overcame the problems. “After a few months, I already felt like an insider. I had even forgotten which language we were speaking in: they – in sign language; or I – with words.”

A World of Dreams

George, who dreams of creating an Armenian clothing brand for the global market, says he has never had any problems with people who hear. One summer when he attended a camp, he struggled for two weeks, and started to think he had gone in vain, but then everything quickly fell into place.

“It’s not that they welcome you with open arms from the first moment, but I know that there may be problems for everyone,” says George. “It is also difficult for a person who hears to approach, and try to make contact. It has to be from both sides. After two weeks, we were communicating with each other so easily and telling each other our dreams – as if there had never been any problems.”

Mary says that mutual respect and understanding is often absent. People frequently look at them strangely. Instead, she asks that others accept them as they are.

“Sign language has indescribable beauty. We all use gestures; it’s just that deaf people use it to communicate. They also try to lip-read,” says Mary.

The eleventh graders hurry to the hall and prepare to show their pantomime presentation. The school is surprisingly noisy, but this is not actually uncommon. In the sewing room, they will soon be finishing the blouse that they have been making for one of the teachers; they are learning new patterns in the carpet-making room; the children in the rhythmic classroom are preparing for their next presentation. It is 4 p.m. and the children in the kindergarten are already napping. A strict timetable makes sure there will be time for playing in the schoolyard, for learning and for acquiring new skills.

Greta, a former student, is preparing to go home but, before doing so, she wants to tell us about herself and her dreams.

“I was born in the village of Shinuhayr. When I was 11 months old, my parents noticed that I didn’t respond to their voices. It turned out that I had a hearing problem,” Greta explains. “I went to the village school up to the fifth grade but I refused to go after that, realizing how many problems I was coming up against; I didn’t understand the subjects.”

Greta, who wanted to learn everything but didn’t know how, told her parents that she would not go to school anymore, so they looked for solutions and moved to Yerevan. Unlike many youngsters whose written Armenian is not that well developed, she writes very well and loves the Armenian language.

“The education here was in two languages and I picked things up very quickly,” Greta says. “I would like sign language to be taught in all schools in Armenia, regardless of whether the school has hearing impaired pupils or not. This will help people understand us in life and give us a chance to integrate quickly into the world of those who hear.”

After graduating from school, Greta attended the Armenian State Pedagogical University’s Faculty of Special and Inclusive Education, hoping to become a surdo-pedagogue [deaf teacher]. She worked for a while but is now looking for a job again. It is not easy to find work when your hearing is impaired.

“Society needs to be open and realize that a deaf person doesn’t hear, and that’s all. A deaf person should also be given the opportunity to learn in an education system where, when deciding on a profession, they can choose on the basis of not just ‘what is suitable,’ but ‘what I want.’”

“If the infant doesn’t understand your teaching, the fault is yours, because you haven’t been able to understand their soul,” she says “You have to get down to their soul’s level and lift them up with you. Society only wins when it begins to look at the deaf as equals.”

Sign language expert Gohar Melikyan is convinced that, if the government has really decided on developing a policy of inclusion and making it an inseparable part of everyday life, then textbooks must be changed to become more accessible to youngsters with hearing impairments. According to her, when we speak of inclusive education, many people understand only physical inclusiveness.

“The Pedagogical University’s Faculty of Surdology does not provide its students with sufficient knowledge. Are they not going to be inclusive school teachers in the near future? But a student cannot teach the coming generation after graduating without completely mastering sign language,” insists Melikyan. “There are not enough sign language class hours, and they are not conducted professionally. This in turn is going to make the complete inclusion of deaf students in the classroom unrealistic.”

The expert says the university education given to people with hearing impairments is a striking example of inadequate education. The only advantage that deaf people have is that their education is free, but free education doesn’t have to mean poor quality.

“At universities abroad, the establishment is obliged to provide a translator for deaf people. This does not exist in Armenia. On the whole, people are accepted into the Pedagogical University, the Physical Culture Institute or the Yerevan State Institute of Theater and Cinematography, but they do not provide a single translator, or video material with sign language interpreters,” says the expert. “I personally know students and graduates who unanimously point out the same problem – that education is inaccessible without translators.”

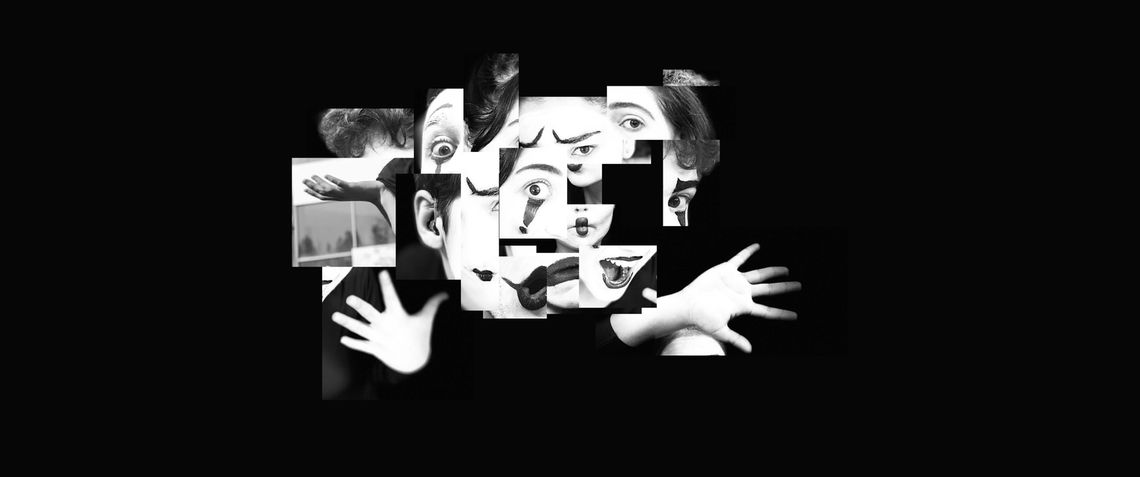

The mime group is waiting for us on the third floor, with Hayk Hobosyan, its choreographer. Pantomime is the youngsters’ favorite class, where they are in their element and they dictate the rules to others. Here, they are like fish in water. The presentation is interactive and I, as an audience member, quickly get included in the game. They have been able to amaze both parents and pupils, and visitors to the school with their presentations.

It is time for me to leave and the eleventh graders start to whisper among themselves.

“They are thinking about a sign name for you.” Once again, the deputy head comes to my assistance.

They show me my name. It doesn’t need to be translated because everyone in the world signs a smile in the same way.

***

The Special School for the Hearing Impaired is located in Nork orchards, one of Yerevan’s greenest neighborhoods. On the way there, asking around, you hear different responses.

“Yes, I think it’s around here. I’ve seen youngsters like that, I think.”

“You mean the school for the deaf and mute?”

Deaf people are not mute. They speak with an indescribably beautiful language: with gestures. The word mute frequently places a perception on our attitude, becomes a barricade between the different layers in our society and we cannot comprehend the true voice, words and mind inside those we consider silent.

The city continues to live with the same rhythm – the noise of the traffic, the chatter of children squealing at the sight of a single ray of the sun, the grumbling of people, drenched from the rain, walking through puddles. This may all be unfamiliar to those who have their own world. And yes, they cannot hear those sounds, but every member of society is responsible for ensuring that the problem of hearing disorders doesn’t become a problem for communicating with each other, making friends with each other, and loving each other.

*Special Educational Complex for Children With Hearing Impairments