I’m a graduate of oriental studies. I work as a teacher and an education-administrator.

Before the war, I worked at the Real School, and I went back to work there after the war.

After I returned from the army, I decided that I want to dance and teach our national dances.

I am a linguist by profession. I have a masters in ethnography. I wanted to continue my education, but I went to the Real School as an education-administrator.

I met Stepan in 2013. We had seen each other during the “Dance in Armenian” events at the Cascade [in Yerevan]. A close friend of mine invited me to their dance group one day. At that time, Stepan had founded the “US” dance group; I started attending.

We dated for three years. After a month, he said, “Let’s get married,” but it dragged on for three years. We were both working. Our school had moved to a new building, there were new challenges, new courses, it was a hectic work process.

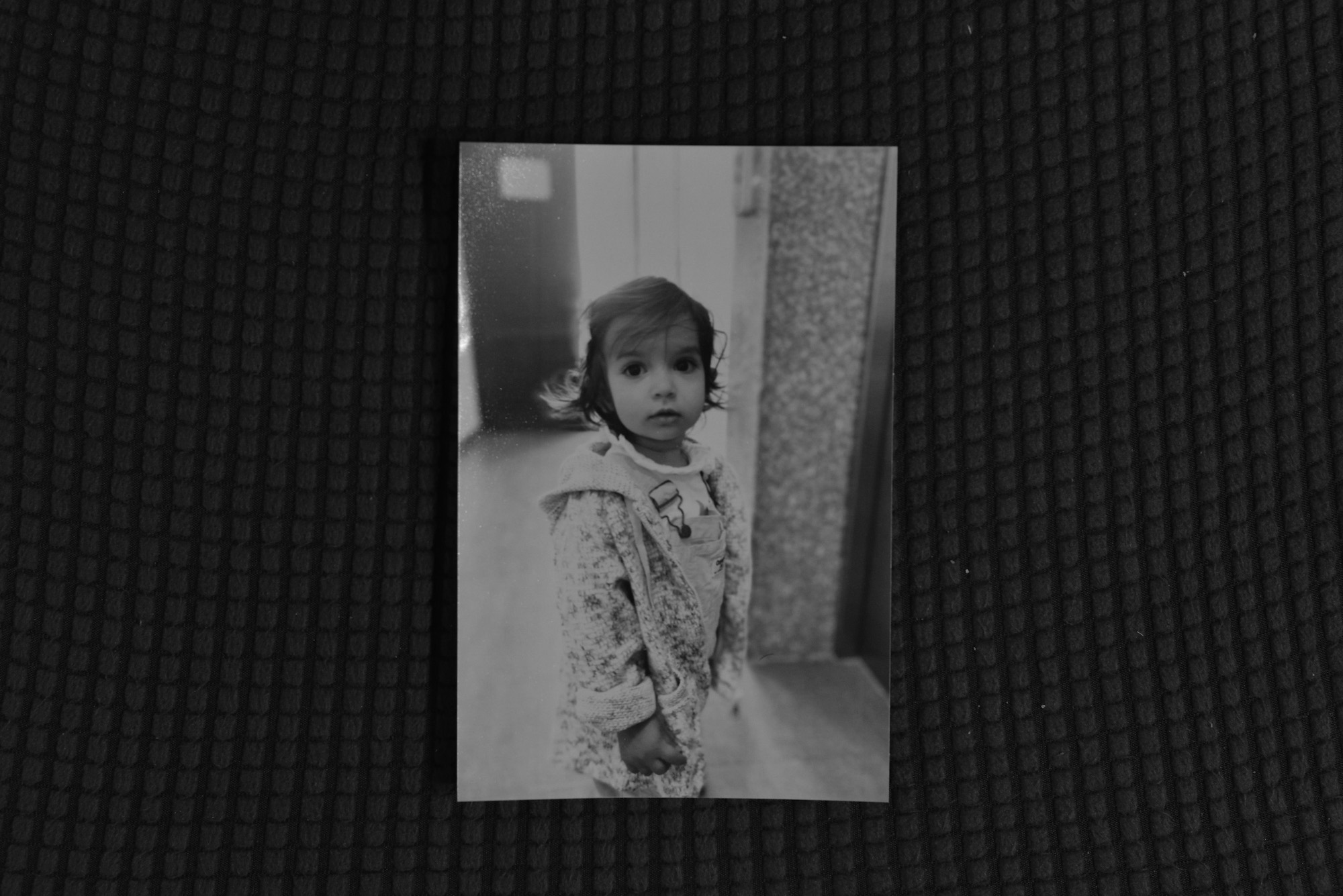

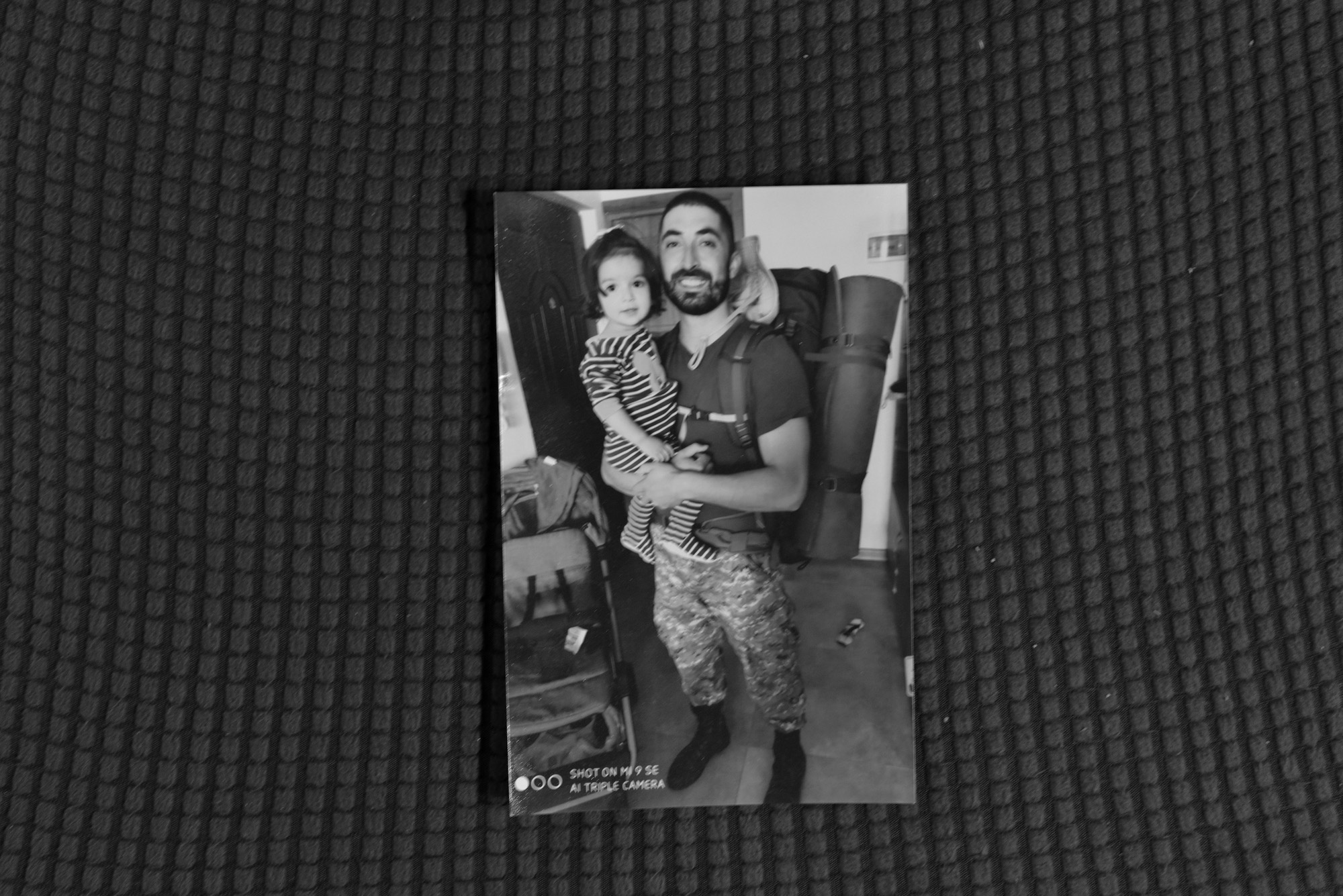

Our daughter was a year old, she used to wake up early, she used to wake me up too. That day a headline in the news, “All along the Contact Line…” caught my eye. I didn’t realize it was a war, I thought it was yet another border clash. After a few hours, Stepan came home and started to pack his suitcase, perhaps that was the cruelest moment.

That evening he came back unexpectedly, the next goodbye was easier. I knew that he could go and never return, but the first goodbye was much harder.

He left, and our one year-old daughter and I were left alone.

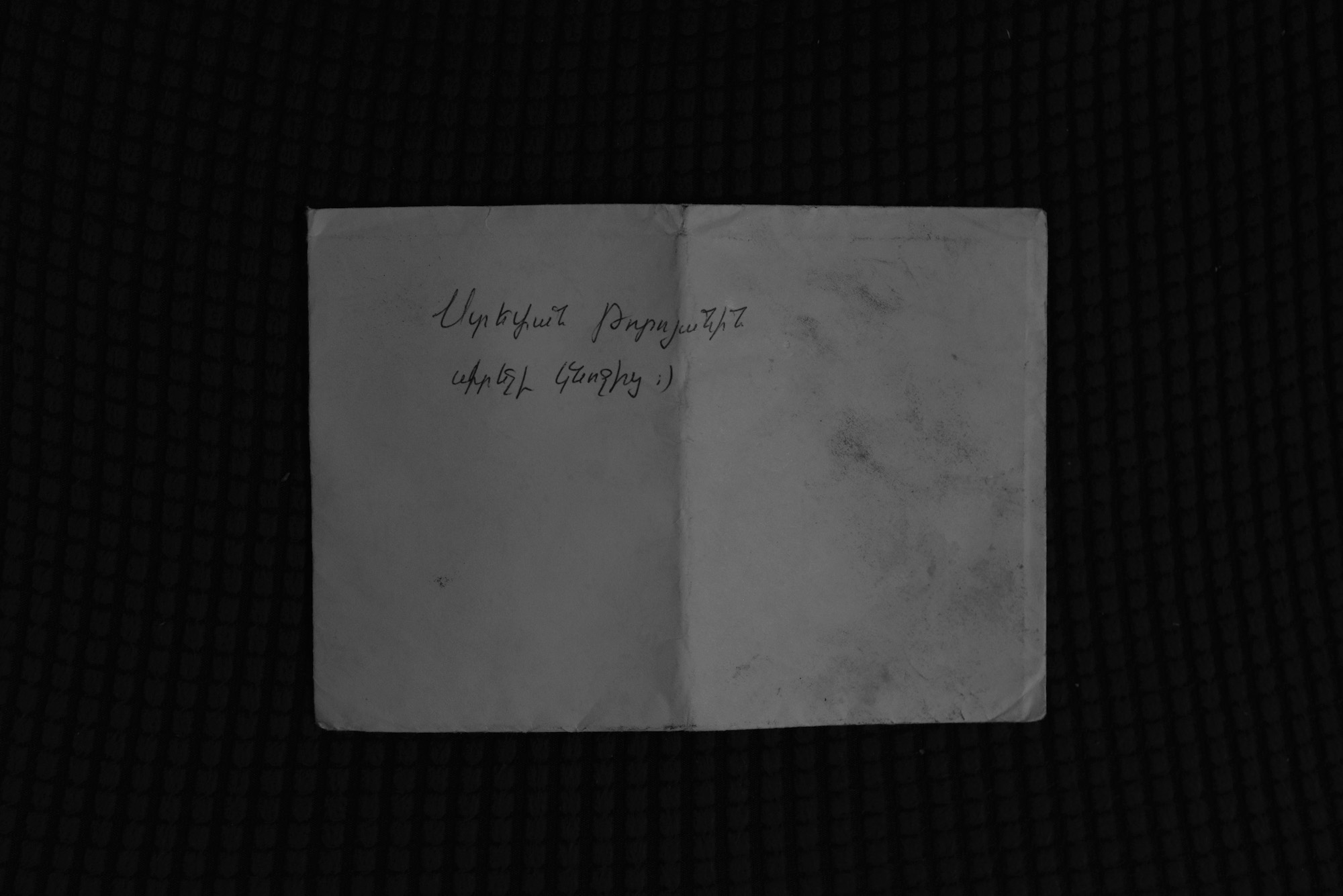

Our daughter’s socks would constantly keep falling off her feet and Stepan used to find them and put them in his pockets. I don’t know how it happened exactly, but before going to war, one of her socks ended up in Stepan’s clothes and he found it once he was there. He said he used to take it out of his pocket and smell her sock.

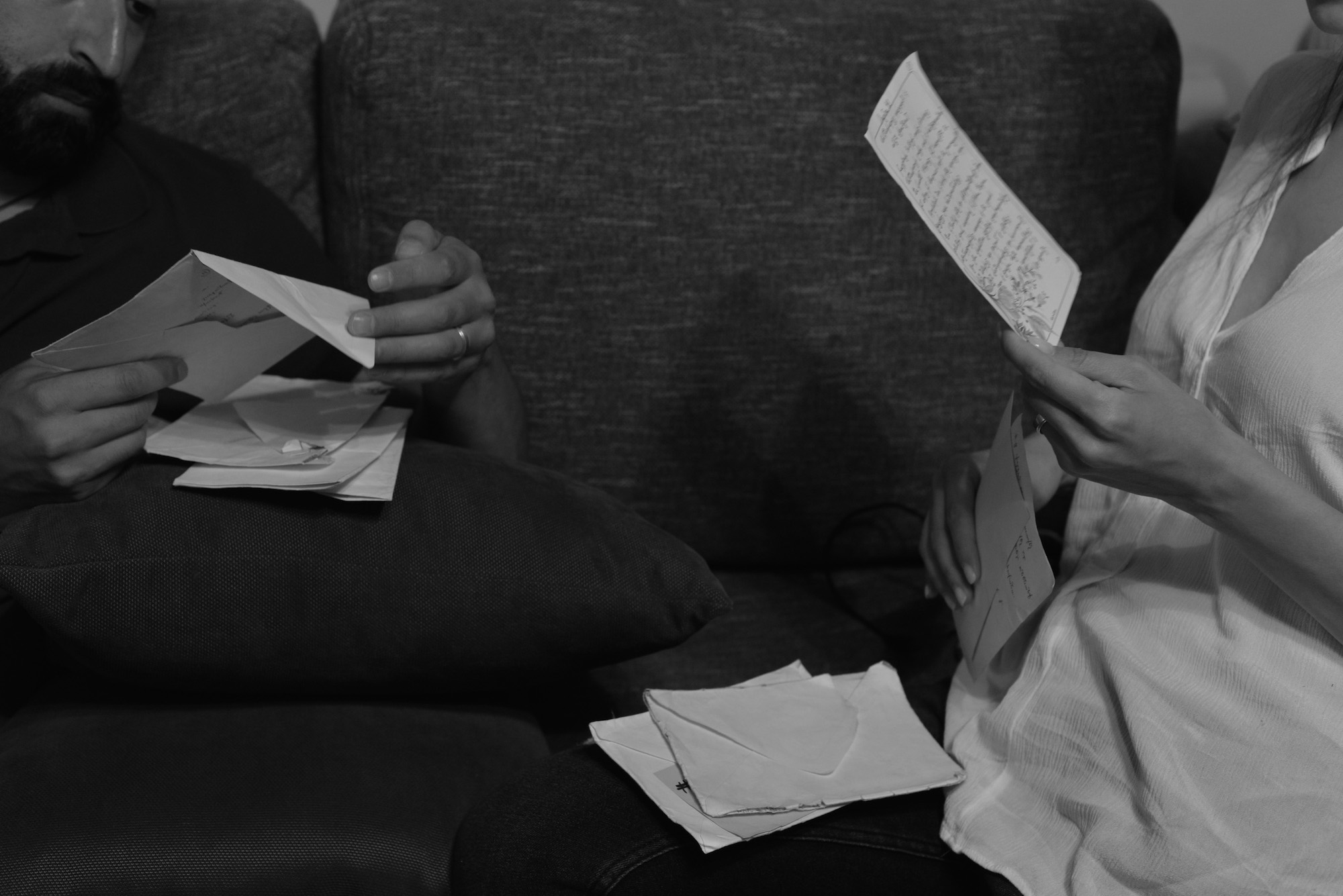

It is difficult to say how we coped with these emotions. We stayed strong, because when Stepan called, I had to be able to speak with a clear head. He would call, I would worry about asking unnecessary questions. I would tell him about all the positive things that I knew had happened, I would say, “No, we will win.” During war you have to believe in good.

Then one of our friends died, people around us were dying.

Some of our students died. We went to funerals. At first it was difficult, we thought that the next funeral could be ours, but then I said, wait, how am I better than them? If my husband dies too, I have to be strong enough to keep standing.

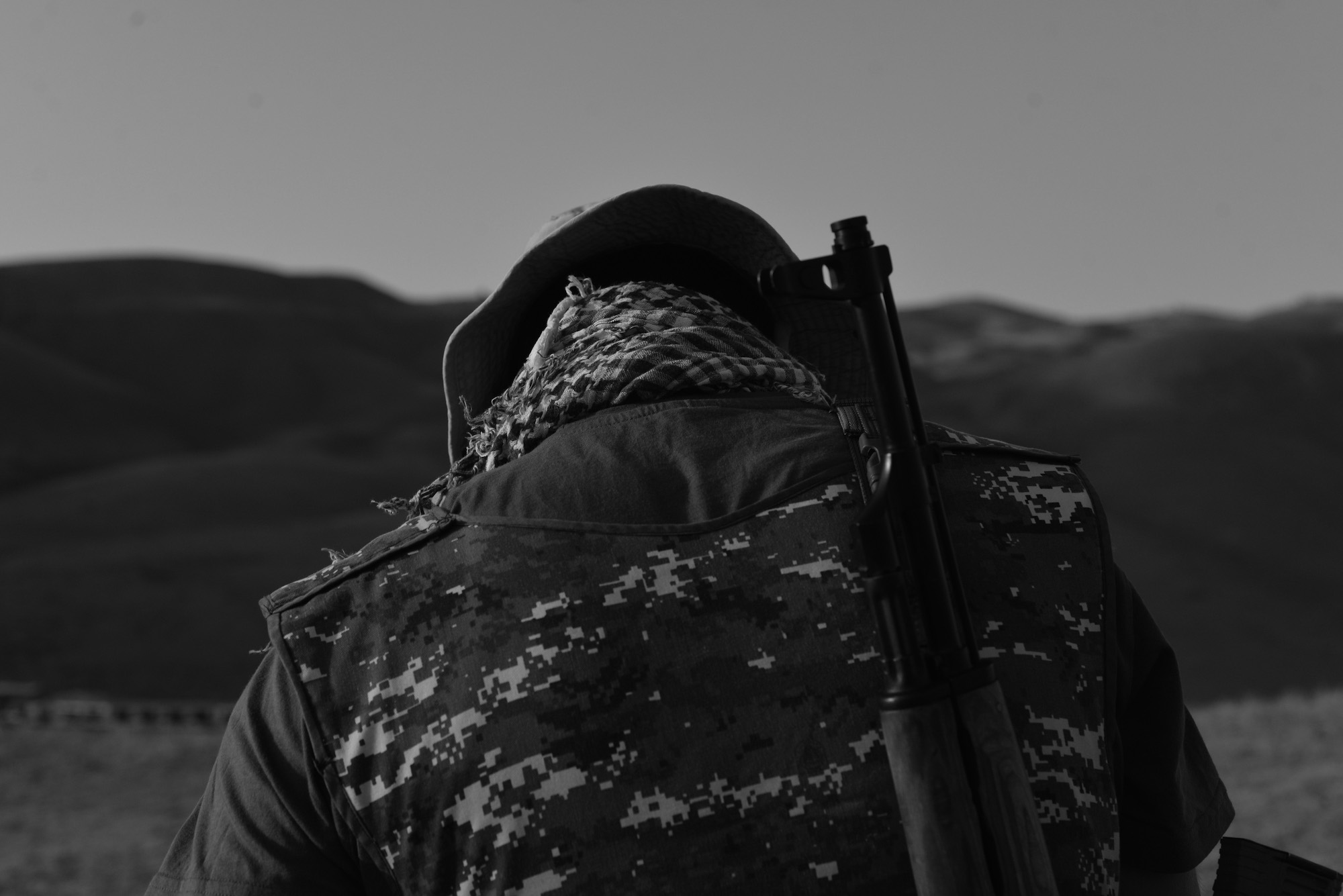

Most of all, I missed my child and my wife. We collected all the telephones of the battalion, only the platoon commanders had phones. I also had a small phone with buttons.

We agreed that everyone should call home once every three days. We used to go 100 meters away from our location, turn on the phone so that if they located it and hit it, the phone would be far away from the location of the unit.

We brought the only surviving phone from our unit back with us to put in a museum.

When war starts, you have to go. The most effective way to protect your family is to go to war. If you do not want the war to reach Yerevan, you have to go and fight there.

After being in the war for a long time, you gradually lose your sense of ownership or individualism. It no longer matters whose house, whose garden, whose flowers it is that you are protecting… Fear also disappears. Overcoming fear is a strong feeling but on the other hand, fear only imposes itself on you when someone else’s life depends on you.

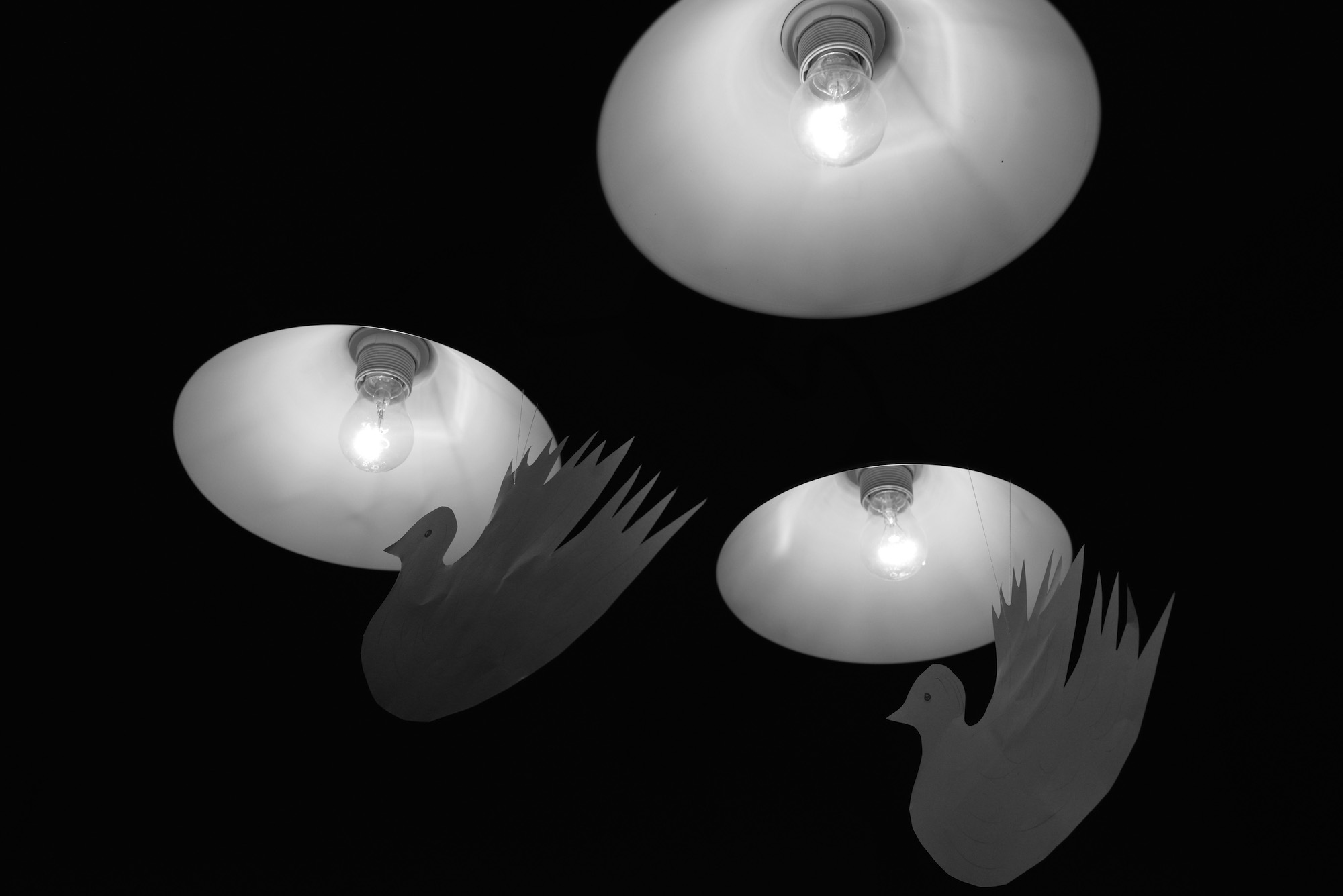

Spiritually, every nation is structured differently; this spirit is often manifested through dance. It seems to me that our national characteristics are most vividly expressed in our dances. I can describe a person by the way they dance.

The national feature in Armenian war dances is meant to toughen the warrior, make him resistant to pain. Shatakhi, Sassoon war dances are danced with hand strikes. And the strong beats of the palms are manifestations of struggle in these dances. Dancing awakens your will.

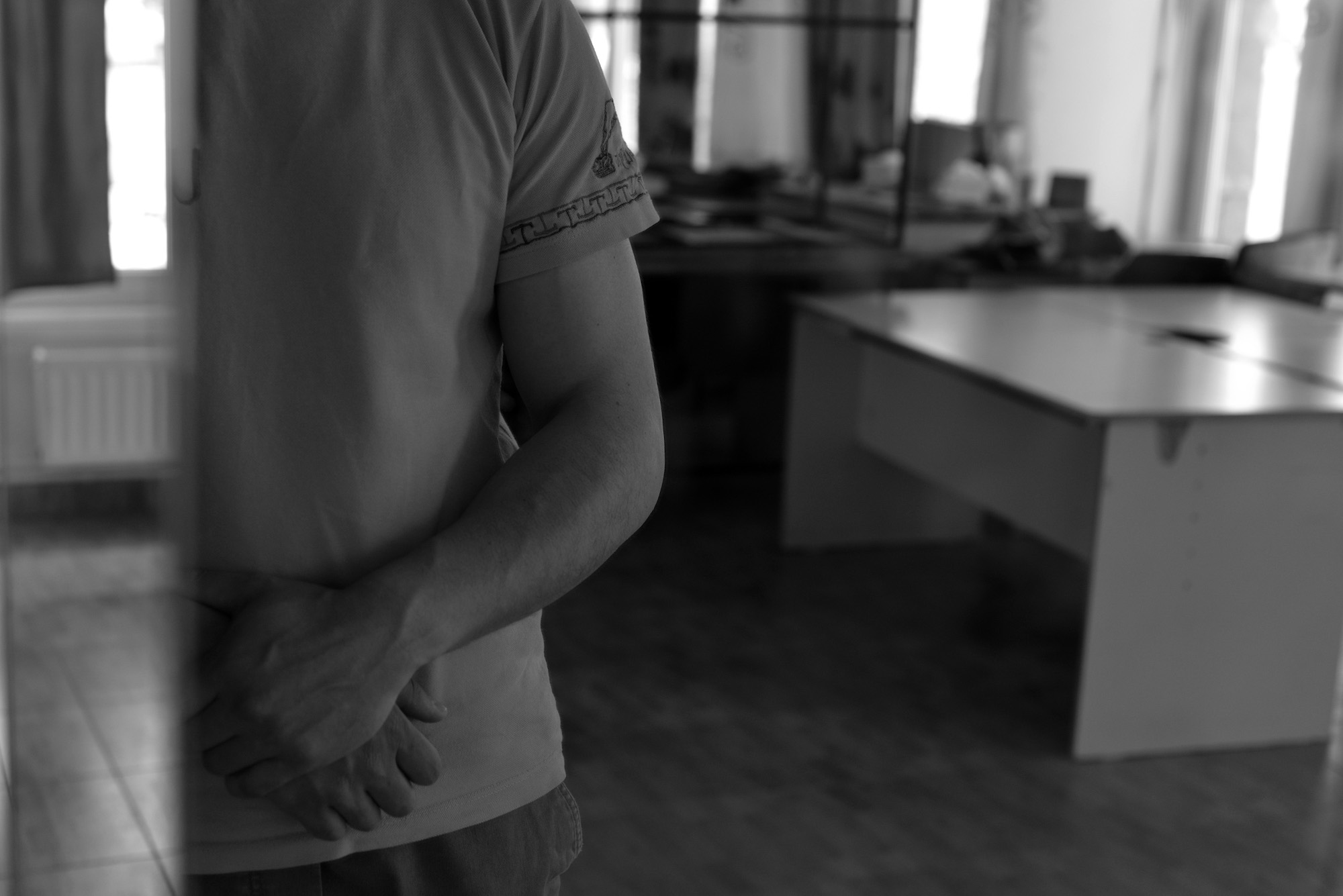

After the war, on the first day, you want to bathe and sleep, stay away from people, from all the questions.

As soon as you get tense, you reach out to your friends who have fought with you. It is hard to communicate with those who have not fought, there is not much to talk about.

It feels like I have become more pragmatic after the war, I approach things more cold heartedly, more strictly. Perhaps it helps in my work, as a leader. Now the school, where I work, includes about 150 people. Rigor helps in this matter.

Now I have a clearer idea of what war is. The war provided an opportunity to overcome fears, to work seriously in a team. It should not feel discharged, weakened.

We talk and talk and talk about the impossible situation that we are in. Yes, we lost in 2020, but the same enemy is still in front of us and there is work to be done. People take it so hard that they think of running away, instead of drawing conclusions and trying to fix something. And when you work to act, to change the situation, the feeling of desperation lifts. Just do the work expected of you.

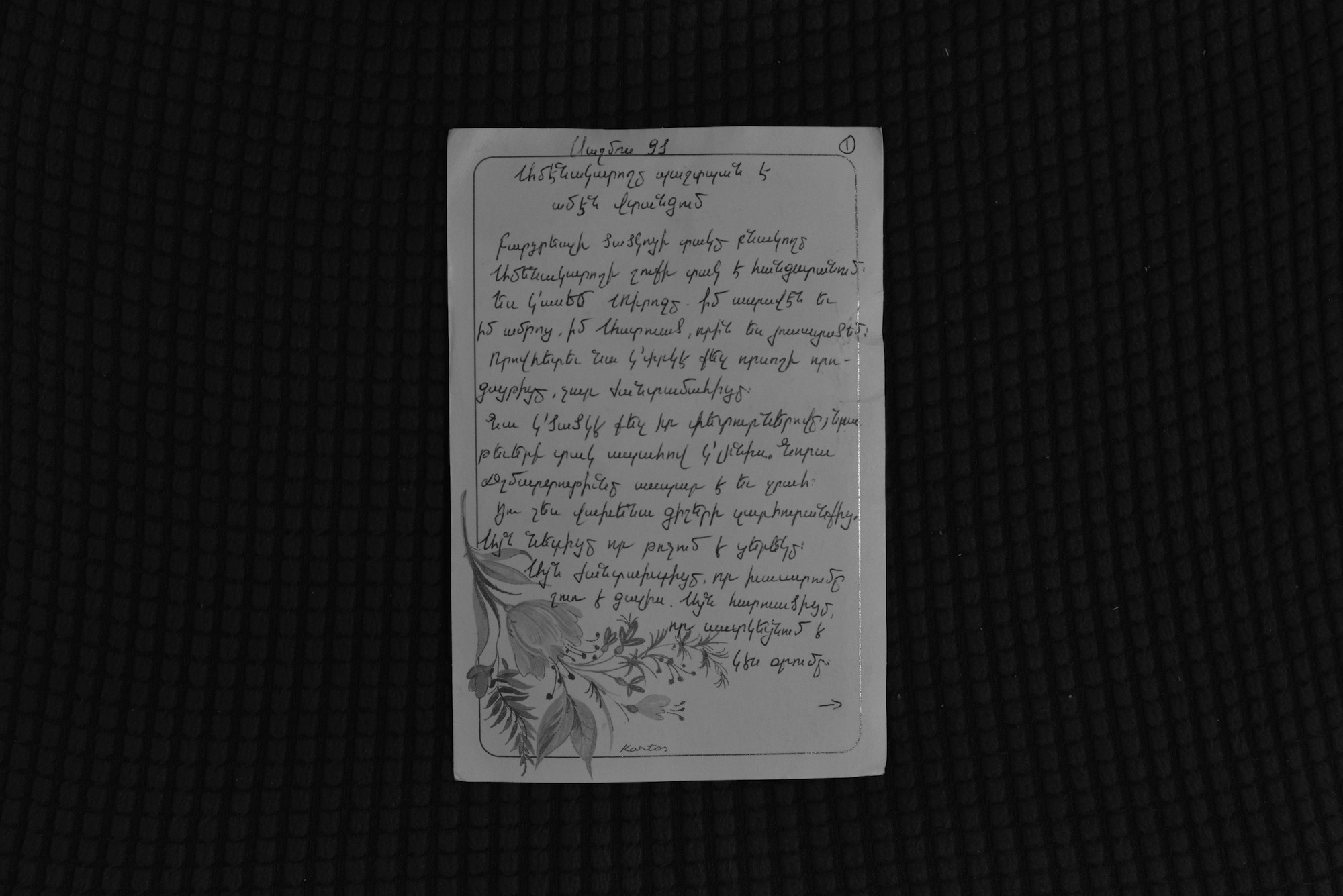

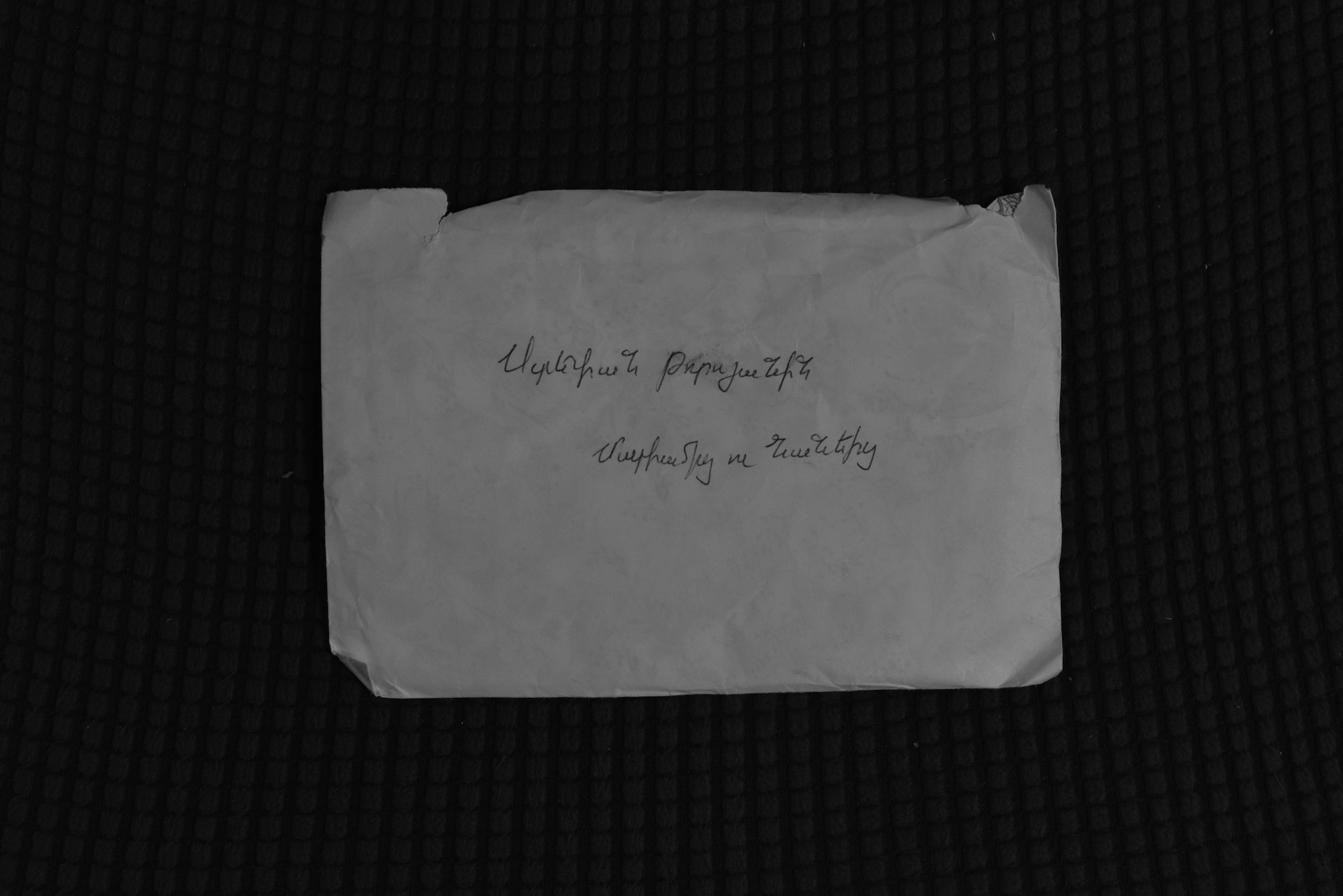

Vaghinak Ghazaryan’s photo essay about Stepan and Mariam was done before the large-scale Azerbaijani attack on Armenia on September 13. Stepan has since gone to the frontlines.