Over the past decade, we’ve seen growing concern for the fate of Yerevan’s architectural heritage, from the 2014 demonstrations to save the historic Afrikyan House to the recent discontent regarding the future of Firdus. While there have always been people who stood up for the preservation of the capital’s historic and cultural landmarks, collective activism seems to be novel. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many buildings of cultural importance were privatized and then later demolished. One of those sites was the Youth Palace, which fell victim to the neoliberal policies of the government at the time. Demolished in 2006, the Youth Palace was considered one of the best examples of modernist Soviet architecture and its memory still wanders in the streets of Yerevan as the generations of the 70s and 80s recall fragments of their youth.

The Birth of the Youth Palace

In the mid-1970s, Soviet authorities decided to build youth centers in the capitals of all the Soviet republics. The aim of these centers, known as Youth Palaces, was to create a platform that would bring together young people to socialize, make connections and have their own space for entertainment and cultural development. The important task of creating Yerevan’s Youth Palace, also known as Kukuruznik,[1] was entrusted to architects Artur Tarkhanyan, Hrach Poghosyan and Spartak Khachikyan. This wasn’t their first collaborative project. The trio had worked on numerous projects together before and would embark on more afterward, composing Yerevan’s architectural soundscape with buildings like the Zvartnots International Airport, Rossiya Cinema (Ayrarat) and many more.

“At that time, there were no means to show the sketch size of the Youth Palace, so we lined up the caps of food cans and built the other halls out of paper, and showed the photo to the people who were supposed to approve it. These were happy days. Artur Tarkhanyan and Spartak Khachikyan were among our greatest architects. We lived like a family, like brothers. That [architecture] was our whole life,” recalls Hrach Poghosyan.

The initial plan of the complex included a hotel, night club, restaurant and swimming pool. Later, they built a sports area, a registrar for civil marriages (known as the Chamber of Solemn Registration of Marriage) and two concert halls with 1000 and 300 seats each. The restaurant on the top floor was one of the main attractions of the Palace, as its floor rotated allowing people to enjoy a 360 degree view of the city. The construction budget was provided by Moscow and all spending was carefully monitored. According to Poghosyan, the final budget was 9.5 million rubles (approximately $5 million today).

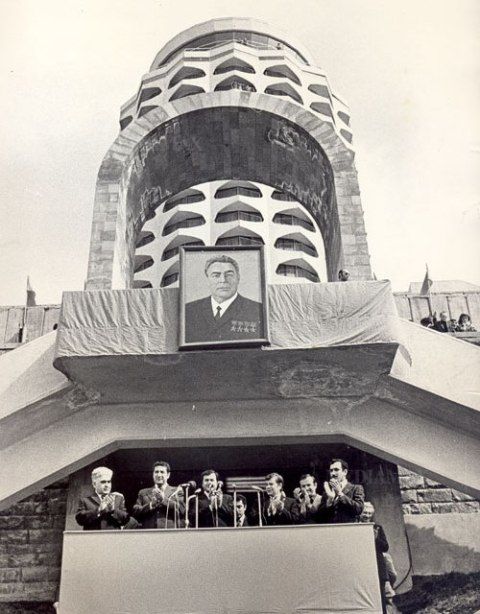

The official opening of the Youth Palace in April 1979.

The Youth Palace opened its doors in 1979 and had all its amenities functioning by the mid-1980s. There were long lines of people at the entrance. Some would be dancing in the night club, some would be on their first date, while a couple would be getting married at the chamber of marriage. For almost a decade, the Youth Palace was the epicenter, the beating heart of Yerevan.

Following the Spitak earthquake of 1988 and Baku pogroms of 1990, for several years, the Youth Palace also served as a shelter for the victims of the earthquake as well as the Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan. What was once a hub for cultural activities and entertainment came to be associated with abandonment and loss. Eventually, in 2004, the Youth Palace was sold to Eduard Avetisyan, the head of Avangard Motors LLC. Despite Poghosyan’s attempts to preserve the building, Yerevan City Hall gave permission to demolish it on the grounds that the building wasn’t safe or functional anymore. Avetisyan justified the decision by claiming that the quality of the building wasn’t adequate and “the hotel rooms couldn’t meet modern standards.” He added, “If it was a historic building built 600 years ago, I would definitely keep it, but we are talking about a building built in the 70s.”

The Memory of the Place

“The remembering of a place may have less to do with the place per se, and more to do with the yearning for the emotion or mood it once evoked.”[2] Indeed, people’s memories of the Youth Palace reveal that its significance didn’t lay in itself, but rather in the sense of excitement, independence and novelty the place brought into their lives – whether it was the novelty of its architectural form or the possibility of new experiences it provided. And while it still remains unclear who and what will fill the void left by the Youth Palace, its spirit continues to live in the memories of those whose youth was in a way interwoven with its existence.

“The Youth Palace was a dream of a new Armenia, a new life,” noted architect Anahit Tarkhanyan, Artur Tarkhanyan’s daughter. “The aura of restraint and fear [of the early Soviet years] was still present. The Youth Palace, with its stretched forms, gave off a feeling that looked toward a new life, toward freedom, toward the sky, toward the universe. You would pass through those main gates, beneath the arch, and leave behind the life that was before… and you would find yourself in a completely new environment of freedom.”

Fragments of Memories

“You could find everything there: a hotel, a swimming pool, a night club, a marriage chamber. There was everything. On the top floor, there was a bar. For those years, it was a landmark building. Some people called it Kukuruznik, but we knew it as Molodyozhni.[3] It was a really stunning building. You could see everything from there.

It shouldn’t have been demolished. It was the symbol of Yerevan. You know, what is Yerevan? That was Yerevan. It’s like demolishing the opera building then justifying it by saying ‘we’ll build something better.’ It’s like destroying the [original Zvartnots] airport terminal. That’s also Yerevan. Look, they demolished the Dvin hotel, right? And then they built a ‘better’ one, but every time I remember the old one, my heart aches. Everyone was complaining, but back then, who cared [about the complaints]? We are such a foolish, destructive nation, so destructive. We destroy everything we have built. Each person only cares about things like extending their roofs or balconies for just a meter, which, they don’t realize, only makes the buildings look grotesque.”

Andranik Jagharyan, 43

“My family was too strict to let me go to the parties there. But I remember how my classmates and I would sneak out from school and hang out there. When I was in the 10th grade, we were getting ready for our graduation ceremony and the dance training was at the Jazz College, which was part of the Youth Center back then. Every time, before our dance class, we all would take an elevator ride in the tower, going up to the top floor and back, just for fun. It was a speedy elevator and you couldn’t find those anywhere else. It felt like an attraction from amusement parks.”

Lusine Babayan, 42

“When it had just opened, I was probably in the 7th grade, too young for anyone to let me go there. But I remember that all the adults, literally all of them, found it obligatory to visit. And then they would say [in a boasting tone], ‘I have already been there.’ There were lines of people. You had to reserve your seat beforehand. It was a special place, like a museum, and people of different social backgrounds would gather together.

I was 17 when I first visited Kukuruznik. I was a university freshman. We went there with my girlfriends to see what it looked like from the inside because we had heard so many interesting things from others. There was a Green bar, a Red bar and a night club. The entrance fee was two rubles for the evening disco. After classes, at about 3 p.m., we would go straight there, drink coffee and stay until the cafe closed and the night club opened. We would hide behind the columns and then, when the crowd came in, they no longer could figure out who had come from outside and who hadn’t. This way, we didn’t have to pay for the disco. But sometimes we would get caught and kicked out.

Back then, the building was considered the most beautiful one in the city. But in my opinion, it wasn’t the best. For instance, I think some old buildings, the Polytechnic, for example, are more beautiful. It was just modern. It was new. It was fashionable. It was the first youth palace, the first place young people could gather, sit down for a cup of coffee, dance. In other places, you could only drink coffee. There was no dancing, nothing like that. There were no discos, not that I can recall. There were only cafes where you could just sit and drink coffee. They had good music [at the Youth Palace]. Very good music for that time, like Boney M. They would play the music of all our favorite artists. Moreover, some young people would help the DJs, bringing in new tapes to renew the repertoire. They didn’t check the music anymore [it was no longer controversial to play Western music].

I felt pity [when they demolished it]. But I didn’t know anyone to hold protests. It was actually the symbol of the 80s, but after serving its purpose for a decade, it had turned into a shelter for the homeless in the 90s. There was no electricity, no heating. It was emptied out.”

Nune Aghazaryan, 56

It was a new type of architecture for the Soviet period, not a traditional one. It was a novelty in architecture, and stood out from other buildings. I used to go to the swimming pool with my friend. Maybe it wouldn’t compete with today’s swimming pools, but for the Soviet times, it was a very good one. They had excellent showers as well.

There was a marriage registry office and in 1998 I got married there. The ceremony was quite solemn. They had a wonderful hall, a huge one. There were beautiful carpets, all those Soviet red carpets. We broke a champagne bottle. There was a wall with portraits of the couples who got married there. [For the people of my generation] it was very common to have your wedding ceremony there.

I don’t remember when exactly they demolished the building, but I don’t have pleasant feelings about it. First of all, why? It wasn’t a very old building. A lot of money had been spent on it. Why did they have to destroy it? Couldn’t they somehow restore it? It really was unclear why. The building is gone, but the sense of it still lingers.”

Anna Gevorgyan, 48

Footnotes:

1. Kukuruza (кукуруза) means corn in Russian. The building got its nickname because of its visual similarity to a corn cob.

2. Marcus, C. C. (1992). Chapter 5: Environmental Memories. In I. Altman & S. M. Low (Eds.), Place Attachment (p. 111).

3. From the Russian word молодёжь (molodyozh), which means youth.