Historical Context

The status of women’s rights and societal role is a telling indicator of the level of freedom and peace throughout history. Modern achievements in women’s rights are the culmination of centuries of ongoing processes, transformation and struggle.

Armenian history remembers many famous women who played influential roles in the development of Armenian statehood. As far back as the 1st century AD, Queen Erato of the Artashesyan (Artaxiad) Dynasty was Queen Regnant of the Kingdom of Greater Armenia, a unique development not only for the Armenian state, but also for its neighbors at that time. Historians have taken note of this fact, but have rarely analyzed its impact on women’s societal position; a woman could not have become the sole monarch if the population, or at least the noble class, of the state did not have a flexible understanding of inheritance and succession. In turn, the milestone is likely to have contributed further to societal acceptance of women in political leadership positions.

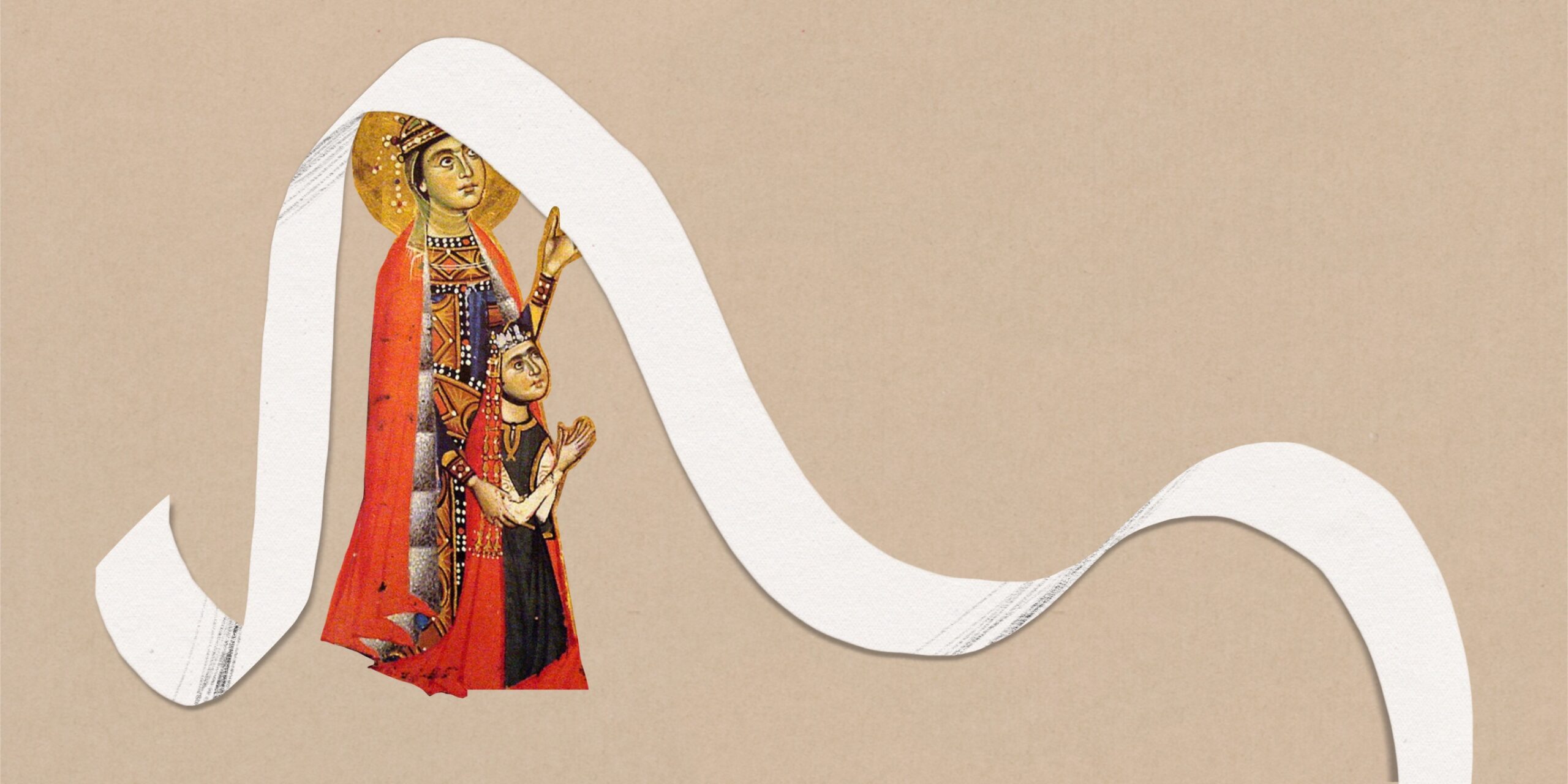

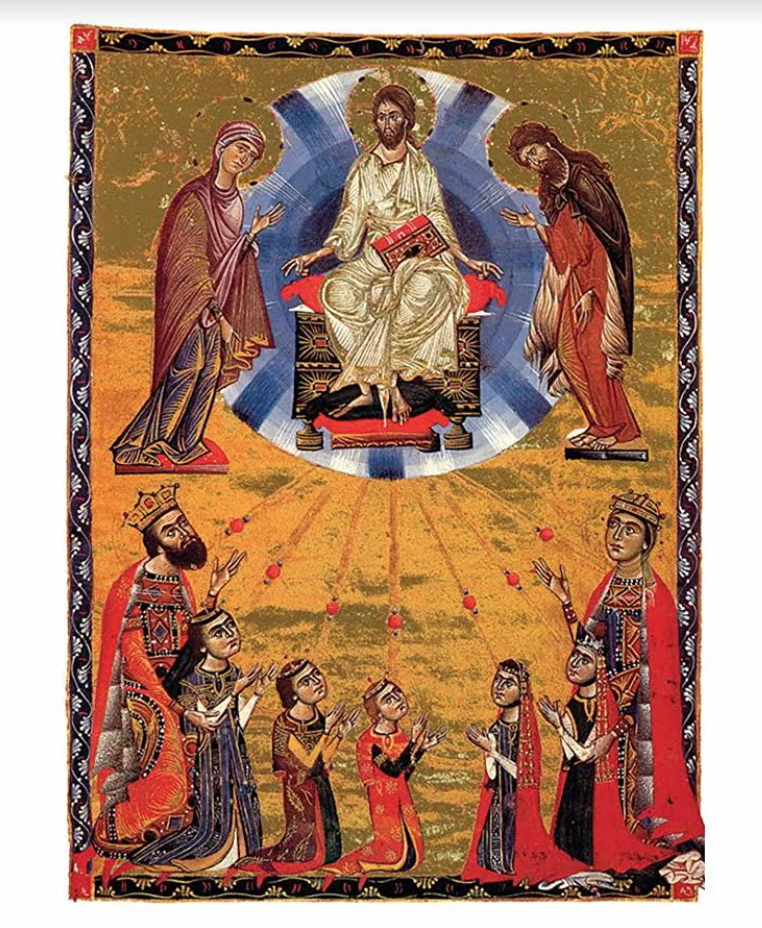

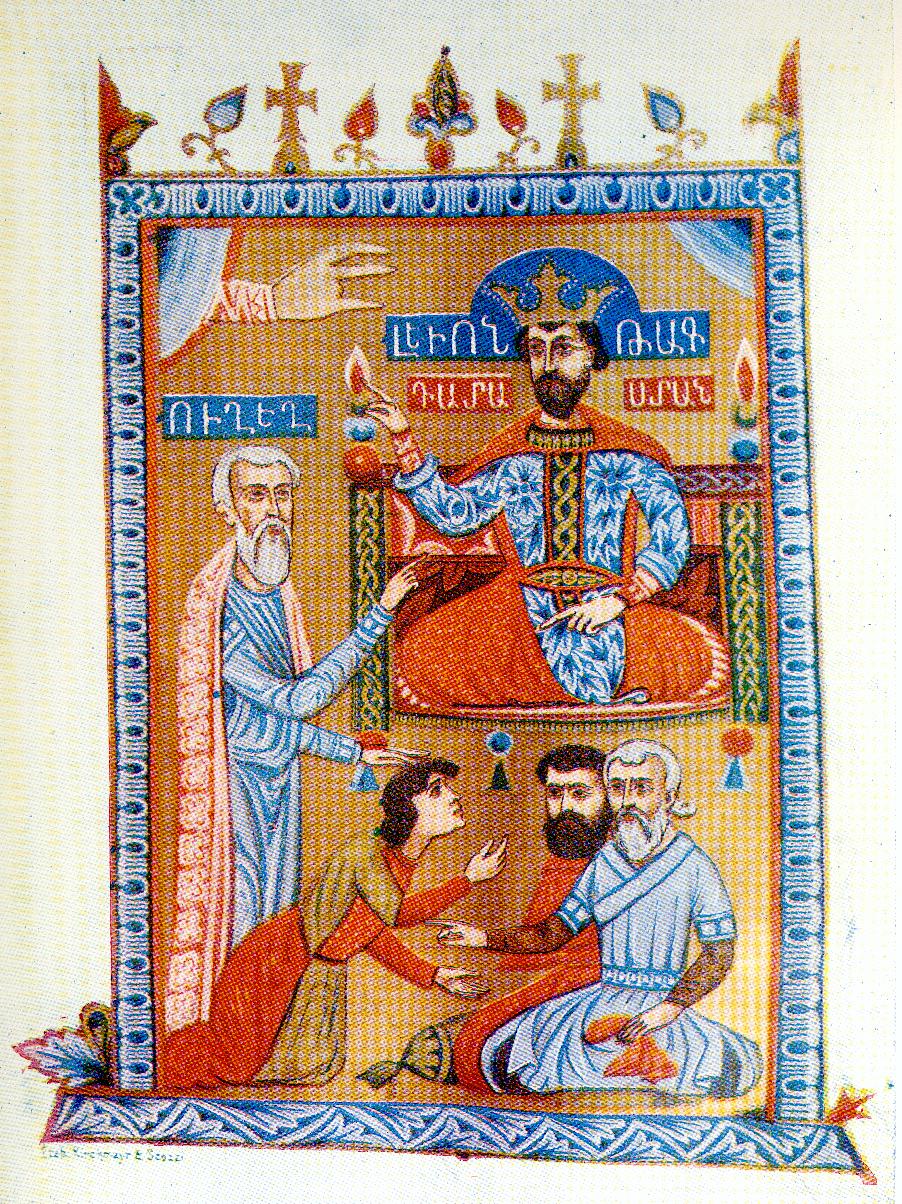

During the Bagratid dynasty (c. 885-1045) and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (c. 1080-1375), Armenian queens and other noble women also played an active role in various spheres of the state’s public and social life through the financing the construction of churches and hospitals, the publication of books, and so on. Queen Katranide, wife of Gagik I Shahnshah (989-1020), and Queen Zabel, whose proclamation as sole heir to the throne by her father Levon I the Great (1187-1198 as prince, 1198-1219 as king) testify to the high legal status and public position of women in the state at that time. Queen Keran, the wife of Zabel’s son Levon II (1269-1289), followed in her mother-in-law’s footsteps and was extensively involved in the social and cultural life of Cilicia during her reign.

It should be noted that, during the same time period, the participation of women in governance also became more dynamic in European countries. For example, Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204) was the queen consort of King Louis VII of France (1137-1152) and then King Henry II of England (1152-1204). She was the mother of King Richard I (Richard the Lionheart) of England (1189-1199). Her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were kings, queens and powerful princes throughout Europe. Eleanor is often regarded as the most powerful woman in Europe in her time.

This article will focus on the social realities and perceptions of the legal status of women in the Middle Ages, specifically in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. It will cover women from different social strata and not just the noble class.

Cilician Armenia in the 13th-14th Centuries

In 1201, Levon I granted trade licenses to the ambassadors of the Republics of Venice and Genoa—a step that brought the Armenian state of Cilicia to a new, higher level of international relations. Merchants arriving in Cilicia from dozens of Italian, Spanish and southern French cities, as well as people from diverse professions had settled in the cities of Ayas, Sis, Korikos, Mamestia and Tarson, where areas were allocated for the construction of their churches, houses, hotels and courts.

For example, in 1215, Levon I reaffirmed the previous agreement allowing the Genoese to have an entire street in the city of Tarson. Newcomers could build baths, gardens, parks, shops and other facilities in their neighborhoods. Cilician Armenia was becoming a multinational, cosmopolitan nexus, where merchants and craftsmen from Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Florence and other Italian cities, Catalans, French, Greeks, Jews and Arabs lived alongside the Armenians. Their numbers started increasing at the start of the 13th century and continued into the 1330s.[1] The Mediterranean Sea and the multinational milieu made Cilician Armenia an exotic locale, where Armenian cultural traditions were synthesizing with various other cultural currents of the world to form a new reality, which was reflected in the form and content of human relations and coexistence.

Paper and Medieval Society

The invention of paper traces to China, but its widespread use in the Middle East and then in Europe began after the battle of Talas in 751, between the Abbasid Caliphate and the Chinese Tang Dynasty; the spies of the caliphate were able to obtain the secrets of making paper from China. Within a short time, paper mills spread throughout the Middle East and Europe.[2] The Middle and High Middle Ages was the period when other types of capital appeared, which gradually transformed the form and content of social relations, coexistence and social classes. The new forms of capital became more accessible and circulated among the general population through paper. Paper was more accessible to various social strata than parchment, and more people could document their wealth and enter into and sign various contracts using it. Documents asserting rights over real estate and personal property became an important guarantee for social standing and facilitated legal structures. Paper became the main catalyst for the formation of new types of capital in the Middle Ages, which ultimately changed the economic relations of Western Europe in particular. The clearest evidence of this development was the emergence of banking houses (Bardi, Peruzzi and later Medici),[3] established in the Italian cities of Siena and Florence from the 12th century.

A silver coin of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia depicting Queen Zabel and King Hethum (13th century).

Miniature from the Gospel of the Queen Keran (1270s), which depicts King Levon II (III), Queen Keran and their children.

The widespread use of paper is evidenced by the thousands of documents compiled by Genoese and Venetian notaries in Cilician Armenia, which range from the purchase and sale of small quantities of spices to legal wills.[4] The significance of documentation was so important that these documents were transported from Cilician Armenia and the Italian trading communities of the Mediterranean and Black Seas, and are still kept in the archives of Italian and other European cities.

Genoese notarial cartularies were large paper notebooks in which notaries kept their commercial and legal records.[5] In the 13th-14th centuries, various advancements were implemented to help regulate Mediterranean trade, the “Commenda” contract being the most popular. Thanks to the Commenda, a merchant could travel from Cilicia to, for example, Venice with a document drawn up by a notary on paper and use it there to receive a delivery of goods as part of transaction. Thus, instead of transporting gold currency back and forth, which could be stolen en route, the merchant only needed to bring the contract, which made for a safer and faster trip.[6]

Paper and Women’s Rights

Paper facilitated documentation, and documentation supported legal rights, rights that could also be held by women. Mkhitar Gosh’s Lawcode (Datastanagirk) and that of Smbat Sparapet (Constable), the brother of King Hetoum I (1226-1269) and the Minister of War,[7] among other things, regulated marital relations and clearly stipulated that women could hold property. The property could have been in the form of a dowry or property acquired during the marriage. The article on the marital rights of spouses in Smbat Sparapet’s Lawcode mentions clothes, linen and different kinds of animals divided between spouses. Furthermore, if the wife had brought the animals into the household as part of her dowry, she could take them back in the event of a divorce; however, the offspring of those animals—born during the marriage—were to be divided equally.[8]

Divorce or annulment of a marriage, and the procedure with which it is implemented, are important indicators of secularism in the legal field in both Cilician Armenia and medieval Western Europe. In parallel with Cilician Armenia, a trend of secularizing laws can be noted in England and France during the same period; divorces were realized based on both ecclesiastical and secular rules, in which the division of property was of key importance.[9]

The English Magna Carta, issued in the early 13th century, was one of the first codes in Europe to protect proprietary rights of women. For example, according to the Magna Carta, a widow was entitled to a share of all the property that her husband had acquired after their marriage.[10]

Smbat Sparapet’s Lawcode was also based on the Assizes of Antioch and Assizes of Jerusalem, which were the main legal codes applied in the Crusader States. There are obvious similarities in structure and format between the Lawcodes of Mkhitar Gosh and Smbat Sparapet on the one hand, and the Magna Carta and the Assizes of Jerusalem on the other.[11]

A will prepared for Januino de Domo of Genoa on September 27, 1277, contains remarkable details of a marriage between an Armenian woman and an Italian man in Cilician Armenia. In the will, de Domo requests the notary to stipulate that his wife Alice (whose Armenian ethnicity is confirmed by the fact that her dowry document was written in Armenian) has all the rights to the dowry and property she receives. However, de Domo appoints his and Alice’s daughter as heir to all his movable and immovable property.[13]

A comparative analysis of legal points in the Lawcodes of Mkhitar Gosh and Smbat Sparapet can clarify the significance of property in marital legal arrangements, and in the case of divorce, its division- depending on the circumstances of the divorce. The law states that, if a wife’s disobedience (not infidelity) is causing trouble between the spouses, it is grounds for divorce, if the two cannot be reconciled. The husband must return all that the wife has brought into the household so that she can take another husband. It is noteworthy that the word “dowry” is not used here; instead, the wording “everything that the woman has brought into the household” is stipulated. That is, this property is not limited to the dowry, but includes all the property acquired by a woman during her marriage. In other parts of the law, the term “dowry” (“prug, proika”, which means dowry in Greek) is used, and apparently borrowed from Byzantine law.[15]

The division of property in the event of a divorce due to family disputes is similar between Smbat Sparapet and Mkhitar Gosh, but is presented in more detail in Smbat’s Lawcode. For example, if both spouses present legitimate grievances against each other, then a woman can take her dowry and wedding gifts, including those given to her by her husband; however, if the wife is the guilty party, then her husband does not need to leave her anything, not even her dowry. In cases where the husband was the only guilty party, he had to pay a fine in the amount of one third of the dowry, if he had married a virgin—if not, he was not obliged to pay a fine.[16]

There is a notable article in Smbat Sparapet’s Lawcode on barren women that is essentially a unique type of alimony. It states that, if the wife is barren and the husband wants a divorce, if the wife does not want to remarry, then the husband is obligated to provide the woman with food and clothing throughout her life. Moreover, the woman takes her dowry with her.[17]

These laws extended to the state’s entire population, not just the noble class. These regulations naturally required documentation, which necessitated a more affordable material than parchment (leather). It is unlikely that a peasant or a member of a lower social class would slaughter their only cow or goat in order to obtain parchment to record their dowry or other possessions, especially if the individual had no domestic animals at all. The wide circulation and accessibility of paper created an opportunity for the broader masses, particularly women, to document and capitalize private property and, as a result, also establish and secure their social status. Of course, backing up these rights has its difficulties (as it still does, even in the 21st century), but the lawcodes of Cilician Armenia at least testify to the aspirations of the state.

Miniature of Sargis Pitsak painted in 1331. A scene of a trial, where King Levon IV (V) of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia is represented.

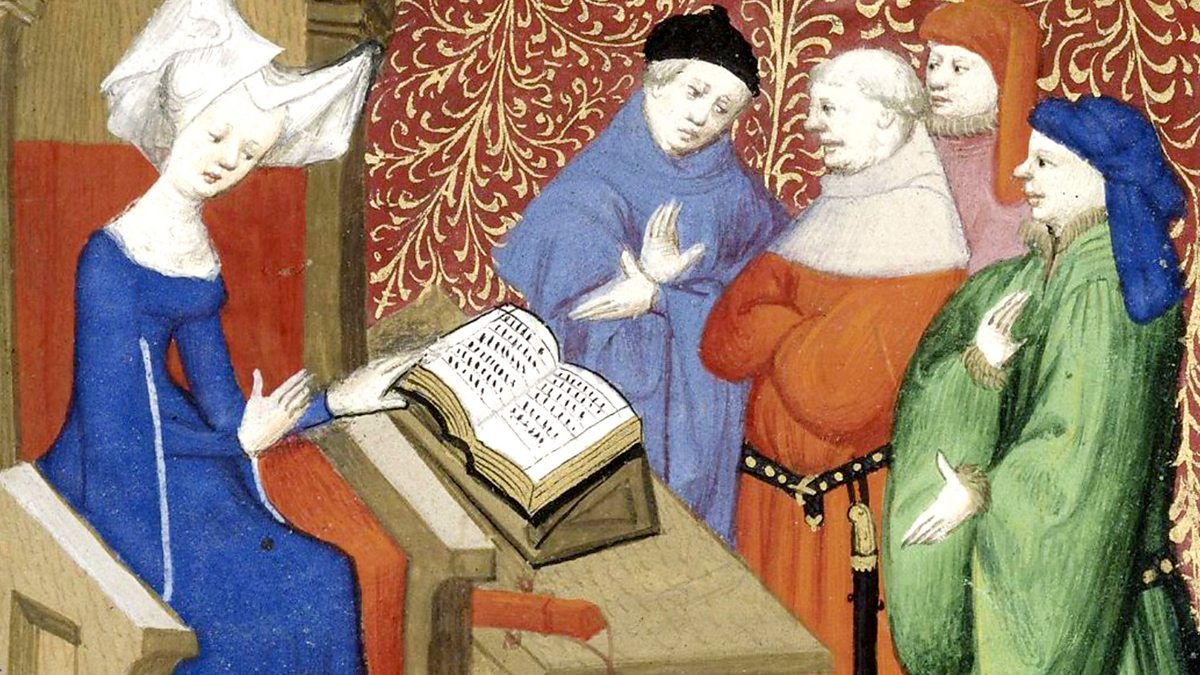

Christine de Pisan (1364-1430), one of the first feminist writers. The image is from her “The Book of the City of the Ladies”.

Then and Now

Women’s rights have been and will remain a global challenge for all contemporary societies. Sometimes, there is a misconception that the historical process of the protection of women’s rights is only a recent phenomenon, starting with the declaration of the International Day of Women in 1910. In fact, the movement is steeped in history. Cilician Armenia took part in the reforms taking place in the European and Mediterranean world of the time. These changes continued throughout the 14th-15th centuries, during the Renaissance, when women such as Jeanne d’Arc or Christine de Pisan (one of the first feminist authors) appear. Christine named her famous literary work “The Book of the City of Ladies”, where she wrote these symbolic lines: “Thus, it is my duty to straighten out men and women when they go astray and to put them back on the right path.”[18]

The issue of equality in societies cannot be solved only through effective governance and passing laws. Equality is primarily a culture of civilized relations, which is formed as a result of lengthy historical processes. For our modern society, the study of women’s rights and their societal role in the context of Armenian history can reveal traditional heritage that has been forgotten but needs to be revived. Often, when talking about the protection of women’s rights, many people have a prevailing perception that these are exclusively imported ideas and not part of Armenian traditions. Therefore, the study of the history of women’s rights and societal role in the context of Armenian history, and the effective presentation of that heritage can help dismantle many stereotypes.