“If I know what is behind Mount Kirs, or where a particular river or stream flows, then knowing the landscape will naturally help in times of war,” says Azat plainly. “We teach the youth these things so they can be prepared.”

Bardak*, the first-ever pub in the capital city of this unrecognized state in the South Caucasus, has become an unusual meeting point. After a devastating war with Azerbaijan (1991-1994), on the surface Artsakh looks like any other country in the world with one exception – it can explode into conflict at any moment.

You wouldn’t know that if you were at Bardak Pub though. The music of Ed Sheeran’s Shape of You is blasting inside and there’s a steady stream of people coming and going. A car pulls up and two young men who had left earlier get out with bags of fruits – apricots, cherries.

“When I opened the pub five months ago, I had exactly four bottles of alcohol on hand,” proprietor Azat Adamyan says. “I had received two of the bottles on my birthday and the other two I purchased after installing an AC unit.”

Humble beginnings to be sure.

Owning and operating the first-ever pub in Stepanakert is not Azat’s only endeavor. A mere 27 years of age, he has his sights on even bigger projects. He launched the Free Step Extreme and Tourism Club five years ago after completing his mandatory two-year military service to “help the youth discover their country” and has now purchased a small plot of land that he hopes to develop into a destination for camping and hiking.

“I didn’t have anything specific in mind; we would get together with my friends all the time, so we thought this would be a cool place to do that,” says Azat.

Now, more than a year after the April War, the young entrepreneur is reflective. Azat intuitively understands the situation of his country, yet refuses to be restricted by it. “If we had more finances, we would revolutionize the tourism industry,” he says.

But Artsakh, about the size of Lebanon, is not any ordinary place to organize hikes. The Karabakh-Azerbaijan Line of Contact is one of the most heavily militarized zones in the entire region and there are constant violations of the ceasefire regime, with both sides exchanging fire on a daily basis. By some accounts, since the signing of the 1994 ceasefire agreement among the sides (Armenia, Nagorno Karabakh and Azerbaijan), thousands of soldiers have been killed. Last April saw the worst flare up of tensions since that agreement came into force: Come to be known as the Four-Day or April War, the region was set to explode in an all out armed conflict. Hundreds of soldiers were killed and the already fragile situation became even more strained.

While his dreams are boundless, Azat understands the limits of his reality. “Wherever we go hiking, whatever heights we climb, is not near the border,” he explains. “We don’t stick our nose near the Contact Line or near military posts.”

Among his many talents, which include playing the violin and the viola, Azat is passionate about developing tourism with purpose. Last year, his club marked five rock climbing sites with the help of a Russian colleague. “We always talk about tourism and if we look at is as a business venture, sure, it can work,” he says. “However, I’m concentrating on domestic tourism.”

Organizing and giving impetus to the kind of tourism he envisions for Artsakh comes with an intrinsic sense of the reality of his life and the life of his peers. “If I know what is behind Mount Kirs, or where a particular river or stream flows, then knowing the landscape will naturally help in times of war,” he says plainly. “We teach the youth these things so they can be prepared.”

Azat quickly switches gears and moves on calmly to other topics as though his statement about war preparedness is as unexceptional as the chair he’s sitting on. “Five years ago, very few people in Artsakh knew about the zontikner [Russian for umbrella] near Hunot,” he says. “Today on any given day, there are always lots of people there.” The Hunot Gorge near the fortress town of Shushi is covered by lush forests where several waterfalls cascade over the entrance of a grotto creating a natural umbrella-like canopy, hence the name zontikner.

Over the years, Azat has created a following of young people, mostly from Stepanakert but also from Shushi who are ardent hikers. He posts information about his hikes and activities on the club’s Facebook page so people can register. “I teach them about safety, how to climb and how to tie proper knots,” he says. He cut his teeth on this lifestyle when he was a member of the Youth Rescue Service, where he says he “learned all the tricks.” Upon returning from his military service, he began putting into action everything he had learned over those two years. “I also taught myself many things thanks to the Internet,” he smiles.

Azat is convinced that the young people need to change their stationary lifestyle. “We always create an atmosphere of motivation,” he explains. “The young people kill time in front of their computers so I have to convince them to participate and once they’re motivated, there’s no turning back.” He acknowledges that the young women are always more interested in the club’s activities. “They are stronger, they have more willpower than the boys,” he says. “During a hike, the guys will ask 10-15 times when will we arrive at our destination, but the girls keep going.”

Nonetheless, he says that the members of the club are like one family. “That’s why when the war began last April, I knew who would be standing next to me,” Azat says.

When news broke that there was a large-scale attack along the entire length of the Line of Contact, Azat was in Shushi. His girlfriend called to say that the war had started. “I thought it was an April Fool’s joke at first,” he says. “I jumped in a taxi and called my friends and we met at the Veteran’s Association to register as volunteers to go to the front.”

Azat and his friends were on the first bus to Talish, the village in Artsakh that came under heavy attack by Azerbaijani military forces – three elderly villagers were murdered, their bodies mutilated. Its residents were evacuated and today, the village continues to be uninhabited.

“I was in Talish for 12 days, on the 13th day I returned home, on the 14th day I registered to help with the supplies and the very next day I was mobilized by the defense army and sent to the Yeghnikner [another military post] for two more weeks,” Azat explains.

When he made the split-second decision to volunteer the first day of the war, he called his mother and told her he was going hiking with his friends to avoid being sent to the front. “I came back from Talish, covered in mud and dirt,” he says. “When my mom saw me she started crying from relief and pride.”

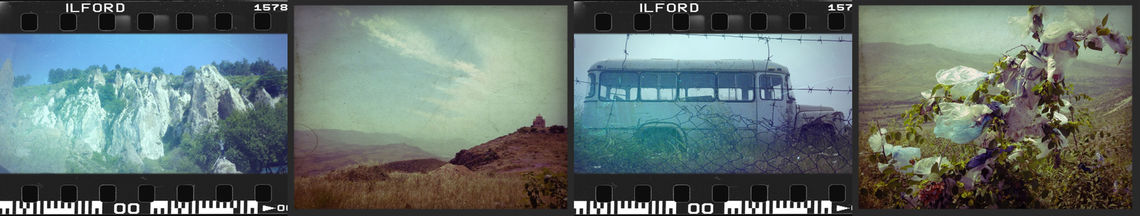

Azat and his friends were on the first bus to Talish, the village in Artsakh that came under heavy attack by Azerbaijani military forces.

April War, 2016. Photo provided by Azat Adamyan.

He explains that when he told her that he was going hiking to escape being mobilized, she had said to herself that ‘my son is not a coward,’ so she was relieved when she found out that he had indeed gone to serve his nation according to Azat.

Now, more than a year after the April War, the young entrepreneur is reflective. He intuitively understands the situation of his country, yet refuses to be restricted by it. “If we had more finances, we would revolutionize the tourism industry,” he says.

And true to his word, he scraped together all the money he had earned and bought a small plot of land near Shushi. “It took me a year to get the money together,” he says. Azat’s dream is to carve out a space where people from all over Artsakh can come to camp and enjoy nature. He envisions it to be a ‘relax zone,’ as he calls it.

Tucked away in a nondescript corner of Stepanakert, Karabakh (Artsakh) there’s a small building that has become the talk of the town. Bardak, the first-ever pub in the capital city of this unrecognized state in the South Caucasus, has become an unusual meeting point.

Sitting in the cool evening air outside of Bardak Pub, Azat returns to how the idea to start a pub began while answering phone calls from patrons wanting a reservation. “We built this structure in 2006 to open a cafe, but never did. After I returned from the 2016 war, I thought it was time to do something with it,” he explains. “I didn’t have anything specific in mind; we would get together with my friends all the time, so we thought this would be a cool place to do that.” So, he cleaned it up, brought in a few tables, and then it was no longer just his friends – it was friends of friends. “It was then that I realized that there were no other places like this in Stepanakert – this is the first pub” he says.

The young man says there are many people in Stepanakert who want to listen to rock, blues and jazz but unfortunately there aren’t any bands to play live. He found a solution for that as well. “I helped the Shushva Band come together here at my pub,” he says. “Now they’re playing at larger venues in Stepanakert.”

By creating a space for young people, Azat is also breaking stereotypes along the way. “People think that girls don’t come here,” he explains. “But they do and by the way, I have more friends who are girls than guys…the guys are always competing, but I’ve learned a lot from the girls.”

Hiking, climbing, promoting a healthy lifestyle and running a pub at the same time might seem counterintuitive but Azat seems to manage it all effortlessly. “I don’t drink and I don’t smoke,” he explains. “People are always surprised and ask how can a barman not drink? I did drink a lot when I came back from my military service, but not anymore.”

Azat believes that working hard always pays off. “People think I’m rich, but they don’t know what I do to get the money together,” he says. “I do all kinds of jobs, people don’t know how hard I work. I’m the only employee at the pub.” And true to his word, each evening after all the guests have left, Azat stays behind and cleans up.

“People think I’m rich, but they don’t know what I do to get the money together,” he says. “I do all kinds of jobs, people don’t know how hard I work.”

As the music winds down inside the pub so does our conversation but Azat continues to get phone calls asking if there are any available tables. “My pub is officially registered, I pay my taxes,” he explains. “Some people say why should I pay taxes, but I say, why shouldn’t you? I’m helping my country.”

*Roughly translates to mess or chaos in Russian