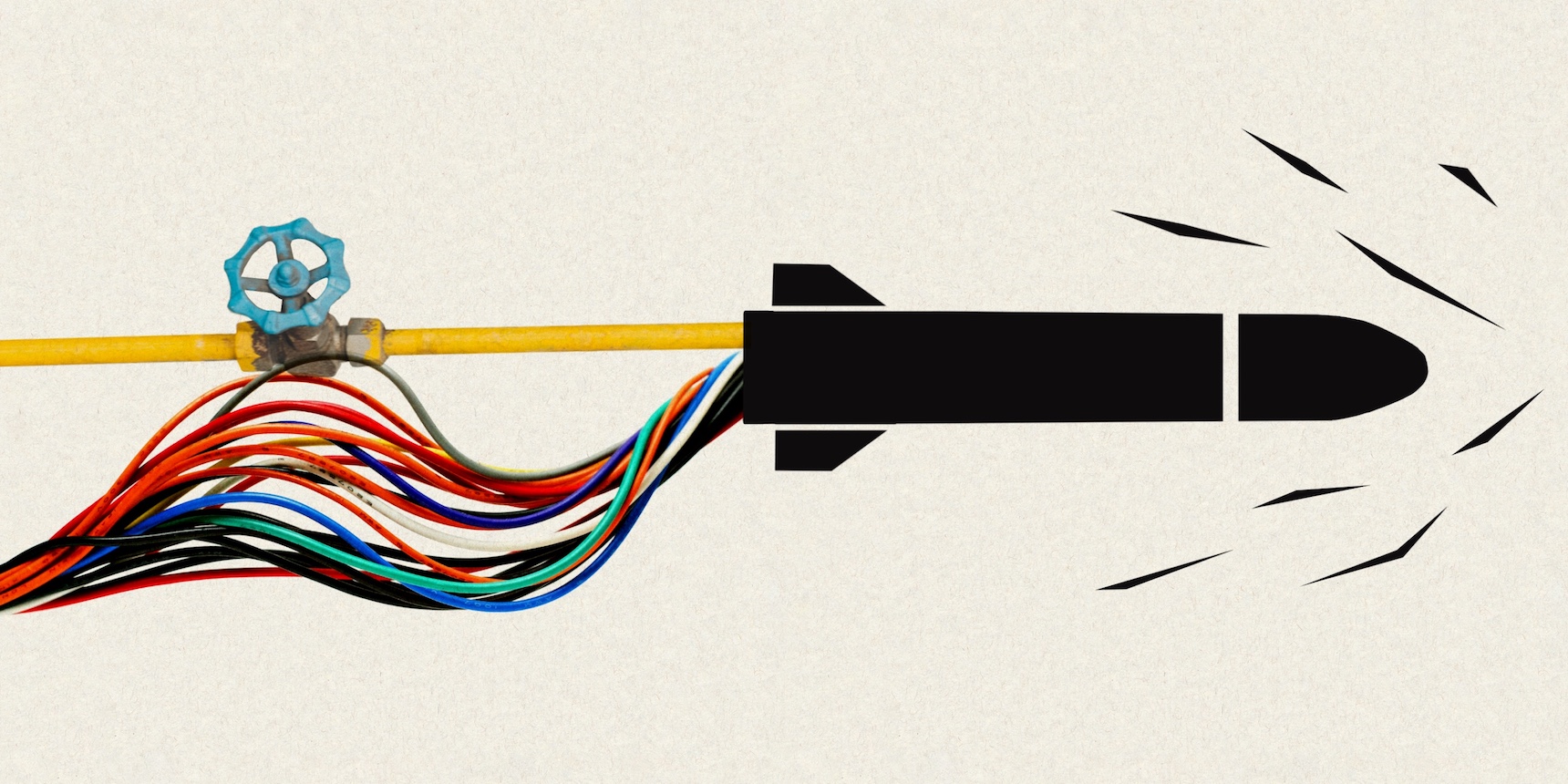

The blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh’s only lifeline, the Lachin Corridor, comes with repeated disruptions of its energy supply from Armenia. For two months already, the region has been facing rolling power cuts and regular suspension of its natural gas supply, as the cables and pipelines providing electricity and gas to Nagorno-Karabakh pass through territories Azerbaijan regained control over after the 2020 Artsakh War.

Yet, before September 2022, Russian peacekeepers had oversight over the gas pipes and electricity cables, with only a small part of them passing through the Azerbaijani-controlled territories near Shushi. When the Lachin Corridor’s route was changed in September 2022, local Armenians in Artsakh and Russian peacekeepers lost control over that infrastructure.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s entire economy is heavily dependent on Armenia, and the blockade of the Lachin Corridor has made it more vulnerable, giving Azerbaijan the ability to weaponize Nagorno-Karabakh’s energy supply and control over its critical infrastructure.

What Happened

Nagorno-Karabakh’s problems with energy began shortly after the 2020 Artsakh War erupted in late September that year.

Nagorno-Karabakh lost most of its hydropower plants in the war, as they were on territory it held in the previous three decades but lost control over. This hit the local economy of Nagorno-Karabakh. The region had just started dramatically increasing its volume of energy production and was suddenly thrown back to being heavily dependent on electricity imports from Armenia, while halting exports.

Since the 2020 war, the pipeline providing gas to the majority of the local Armenian population remained mostly in the Russian-controlled Lachin Corridor with a part going through territory near Shushi, controlled by Azerbaijan.

The new reality has made energy supplies a problem for Nagorno-Karabakh. In March 2022, the region’s gas supply was suspended for over a month due to damage to the pipe near Shushi, leaving the population without heating in sub-zero temperatures.

The authorities of both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh blamed Azerbaijan for deliberately blowing up the pipeline. Azerbaijan denied the accusations and in the meantime denied repair crews access to the area. Azerbaijan repaired the damage about three weeks later, but after a few days, the gas supply to Nagorno-Karabakh was cut off again; this time, Armenia accused Azerbaijan of shutting the valve it installed when repairing the pipe.

The suspension of the gas supply caused people to begin relying on firewood and electric heating systems, which caused additional pressure on the electricity grid, risking more damage and power cuts.

All that, however, was when Nagorno-Karabakh was receiving uninterrupted electricity supplies from Armenia.

In September 2022, the Lachin Corridor’s new route was opened, just north of the city of Lachin (Berdzor). The electricity cables and gas pipelines remained adjacent to the old road, entirely under Azerbaijani control.

The Nagorno-Karabakh authorities stated that moving the electricity wires to the new, Russian-controlled areas would take some time, while the issue of gas pipelines was said to be more complicated.

“It will take time to move electricity cables. In terms of gas supply […] other solutions should be sought,” said Hayk Khanumyan, the then Minister of Territorial Administration of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The Azerbaijani government-orchestrated protests that blockaded the Lachin Corridor in December 2022, allegedly against environmental issues, were accompanied by numerous instances of damage to the electricity and internet cables and the gas pipeline bringing crucial communication links and energy supplies to the besieged region.

About a month after the blockade, the only cable supplying electricity to Nagorno-Karabakh was damaged. No details were given from the Azerbaijani side as to why the electricity supply to Nagorno-Karabakh was suspended, while the Armenian side again accused Baku of deliberately damaging the cable and of denying repair crews access to the area. Since then, Nagorno-Karabakh has relied on limited local production.

Due to the shortage, the authorities in Stepanakert introduced rolling power cuts throughout the region, starting from daily two-hour cuts to three two-hour cuts, and increasing them to daily six-hour cuts.

With disrupted gas and limited electricity supplies in winter’s sub-zero temperatures, woodburning stoves have become the most reliable source of heat. With over 95% of Nagorno-Karabakh used to using gas for heating, especially the capital Stepanakert, where more than 50,000 Armenians reside, switching to burning firewood has been a difficult adjustment.

Many facilities and residential buildings in Stepanakert have not been adapted to using wood burning stoves and some residents lack firewood for heating. The government started allocating firewood and woodstoves to those who need them.

The disruption of the energy supply has also caused the postponement of planned surgeries in hospitals. To save energy for urgent treatment, schools and other educational institutions have gone through several closures since the blockade. Classes resumed after a week’s restoration of the gas supply. However, repeated gas cuts and the low pressure of the gas after restoration has not allowed residential homes and state facilities to be heated sufficiently.

Gas stations have also been affected, disrupting the public transport schedule and depriving residents of the ability to move freely within besieged Nagorno-Karabakh.

Prewar Reality: Exports and Imports of Electricity

The electricity supply to Nagorno-Karabakh from Armenia has not always been a problem: before the 2020 war, both countries were trading electricity and looked forward to a future of cooperation.

Energy production in Nagorno-Karabakh was undergoing a significant shift before the 2020 war, with the region achieving unprecedented milestones in electricity production. The hydropower plants — the main source of production — became profitable in Nagorno-Karabakh in the latter part of the 2010s, reaching their peak just before the 2020 war.

In 2016, over a dozen hydropower plants were operating in Artsakh, increasing to 18 in 2018. By early 2020, that number had grown to about four dozen hydropower plants operating in different regions of Nagorno-Karabakh. A number of small hydropower plants were under construction when the 2020 Artsakh War began.

The hydropower plants, while boosting the economy of the region, also drew the attention of investigative journalists as many of the hydropower plants built in the Kalbajar (Karvachar) and Lachin (Kashatagh) regions belonged to officials from Armenia and Artsakh.

The total capacity of all these hydropower plants was about 187 MW, which allowed Artsakh to provide electricity to the local population and also export it to Armenia.

Nagorno-Karabakh was one of three entities, along with Iran and Georgia, that both imported and exported electricity to Armenia. Armenia produces an average of 7-8 billion kWh of electricity per year, with about 200 million kWh being delivered to Nagorno-Karabakh before the blockade.

About the same amount of electricity, from 150 to 200 million kWh, was exported annually from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. The Armenian government had plans to import a historic high of 330 million kWh of electricity from Artsakh in 2021.

Due to the war, however, Armenia had to meet Artsakh’s demands at the expense of its own domestic needs. Replacing imports from Nagorno-Karabakh with locally produced energy was much more expensive.

Nagorno-Karabakh, in turn, had to decrease exports to Armenia almost to a halt to meet the local demand for electricity with reduced capacity.

Hydro Power Plants Lost in the War

Nagorno-Karabakh stopped exporting electricity to Armenia in late 2020, following the November 9, 2020 ceasefire agreement between Armenia, Russia, and Azerbaijan. As a result of the war, Artsakh lost territories inside and outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), along with 29 of the 37 hydropower plants that operated in those areas.

In 2021 and 2022, Nagorno-Karabakh started exporting small amounts of electricity to Armenia. The figures, however, are not comparable to pre-war volumes.

Between January and September 2022, Nagorno-Karabakh exported only 2.5 million kWh of electricity to Armenia. Before the 2020 war, the total amount of exports was around 225 million kWh.

Data from Armenia’s Public Services Regulatory Commission shows that Nagorno-Karabakh used to import most of its electricity in late autumn, early spring and in the winter months, exactly when Azerbaijan blocked its lifeline –– the Lachin Corridor –– disrupting gas and electricity supplies.

In 2019, for example, Nagorno-Karabakh imported a total of 69 million kWh of electricity, about 55 or over 80% of which were delivered in five months — between January and March and in November and December.

In the first nine months of 2021, the Artsakh HEK [HPP] reported the production of over 150 million kWh of electricity. One of the reasons the Artsakh HEK OJSC, which includes the seven hydropower plants currently operating in Nagorno-Karabakh, managed to survive the war was that its largest hydropower plant, Sarsang, remained under Armenian control. This helped maintain a diminished but crucial amount of local production in the first year after the war. The Sarsang plant, however, had to decrease its production capacity due to security issues, as the areas adjacent to the reservoir are now under Azerbaijani control.

According to data for the second quarter of 2021, the production volume of the Sarsang hydropower plant has decreased by 30%.

What’s Next?

With the blockade persisting with almost no sign of being resolved soon, the problems caused by the energy shortage promise to worsen, with the people of Nagorno-Karabakh facing longer power cuts and more difficulties with heating. This is in addition to the suffering caused by the looming humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh due to the shortage of food, medicine, and other crucial goods caused by the blockade.

Despite reports about humanitarian aid from Russian peacekeepers and the International Committee of Red Cross being sent to Nagorno-Karabakh, the region still needs its access to supplies from Armenia restored –– supplies which amounted to at least 400 tons a day before the blockade.

Armenia awaits the International Court of Justice’s decision regarding its request to impose interim measures on Azerbaijan and order to open the Lachin Corridor it has blockaded for two months. Meanwhile, the international community continues to call on Azerbaijan to ensure the freedom of the movement for Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. At the same time, these calls do not go beyond statements.

Azerbaijan is taking advantage of its control over energy supplies to the region. The gas supply keeps being cut by Azerbaijan, as officials in Nagorno-Karabakh report. The most recent cut was reported on February 6 and then again on the 8th, a few days after it had been restored. The new supply was fraught with low pressure and was barely enough for heating homes or operating gas stations.

The possibility of restoring electricity supplies is not even being voiced by the Nagorno-Karabakh government, keeping forecasts for the future bleak. Authorities in Stepanakert refused to give details about the production of electricity in Nagorno-Karabakh after the start of the siege and the readiness of the region to face a longer blockade, saying that the relevant information is “classified”.

One phone call from Putin to Aliyev would lift the entire blockade of Artsakh.

The Russians are going along with the blockade simply in order to pressure Armenia to obey Russia.

That is, Russia has kidnapped Artsakh and is holding it hostage.

As “peacekeepers,” Russians are obligated to break the entire blockade.

As for the Azeri “demonstrators” in the road, the Russian “peacekeepers” merely have to march down the road and order the Azeris to step away and go home.

That would take about 10 minutes.

That more Armenians are not stating these obvious things means that there is something politically and psychologically wrong with us.

The Armenian – Russian relationship is just plain sick, and it’s time for Armenians to say so out loud.