In the small courtyard of the American Orphanage in Greece, barefoot children dressed in uniforms, are impatiently waiting for a miracle. Their deep sad eyes, witness to unspeakable horrors, are shining for the first time.

Shahen has promised to play for them.

The beautiful melodies, coming from the mournful strings of the violin, carry the orphans back to their lost families and to their faraway homeland.

The melodic trance of the children is broken when someone suddenly yells from the building,

“Who’s playing that music?”

A minute later, Shahen appears in the headmaster’s office.

“It was me, Sir, I was playing the violin.”

The angry eyes of the headmaster stare at the violin.

“You have just survived the massacres and now you are having fun? Give me that violin,” he says.

And then the sound of breaking wood.

Shahen sees the broken pieces of his violin scattered on the ground.

It would be a defining moment in his life.

Today, in a small room in the basement of the Aram Khachaturian House-Museum in Yerevan, Shahen’s son, 85-year old Martin Yeritsyan, proudly continues his father’s vocation.

“In 1925, my father established the first violin making school in Armenia with the help of Yeghishe Charents,” Martin says. “It was the first studio in Soviet Armenia to make violins, mandolins, guitars, cellos, and various musical instruments.”

Thanks to the efforts of Shahen Yeritsyan, today Armenia has an advanced school of violin making. Martin Yeritsyan acknowledges that his father’s journey from an orphanage in Greece to becoming one of Armenia’s greatest luthiers was paved with heartache and loss.

“My father Shahen and his brother Masis, were genocide survivors from Trabzon. After they managed to escape the massacres in Western Armenia, they lived and worked with Kurds for a time until they finally reached the American Orphanage in Athens, Greece,” Martin explains.

It was while Shahen was in the orphanage that he managed to buy a violin from an Armenian woman to play music and entertain the orphans…

After several years in the orphanage, Shahen moved to Soviet Armenia. His brother, Masis, traveled to France to continue his education.

After years of separation, Shahen finally persuaded his brother to also move to Armenia. “In 1932, after many reassurances by my father, Masis also arrived in Armenia,” Martin says. “He was a noble man, also a wonderful violinist who knew several languages.” However, during the political repressions in the Soviet Union, Martin’s uncle Masis was arrested along with many other intellectuals, including Yeghishe Charents and was deported to Siberia. Shahen never heard from Masis again.

Since childhood, Martin Yeritsyan watched his father making instruments. During a career that spanned 67 years, Martin produced over 600 instruments. “My father played a crucial role in the lives of many famous musicians; he provided them with wonderful instruments and eased their long road to success,” Martin says. He remembers that he made his first violin with the help of his father when he was a 23-year old student at the Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory.

“I became a violin maker thanks to the knowledge and experience I received from my father. I traveled extensively and it was a great opportunity to become familiar with various European luthiers, to explore their instruments and learn from them,” he says.

As Martin works on a new violin in his workshop, he says that the length of time it takes to make an instrument depends on the master, not on the instrument. The master is the one who needs to know every single detail about the instrument.

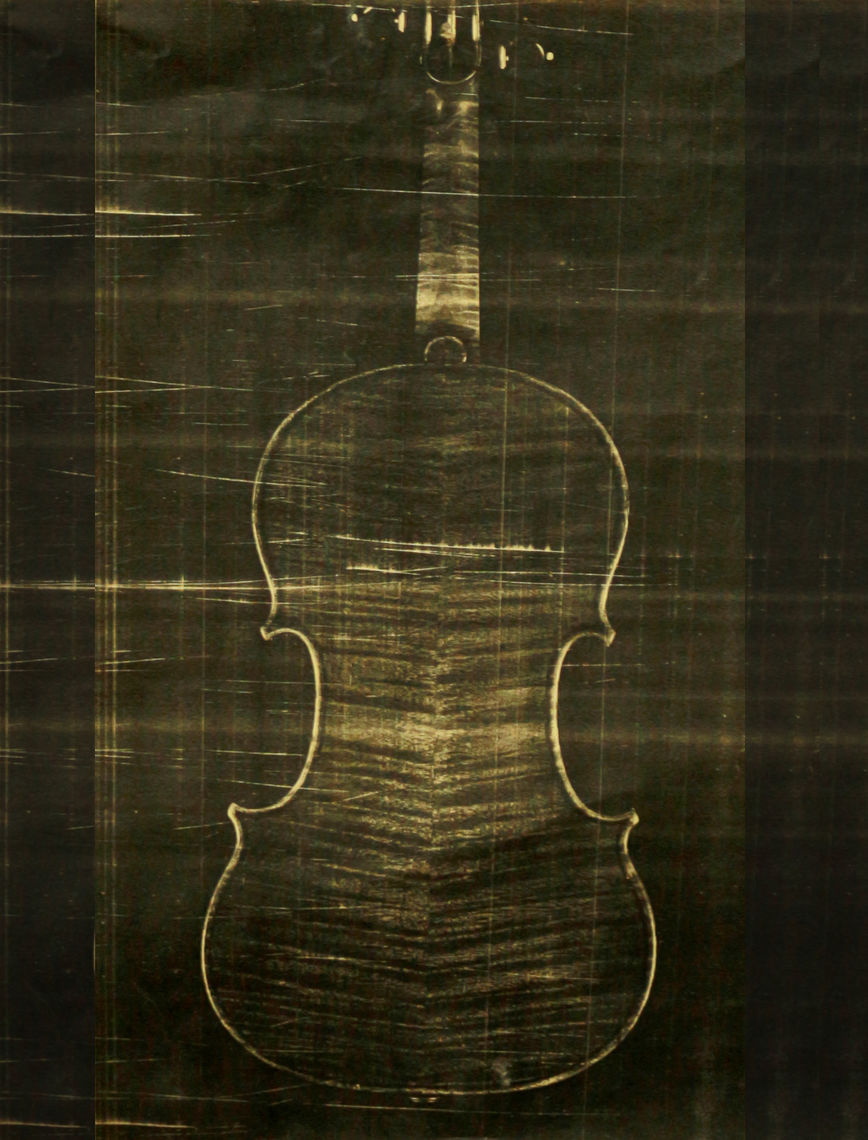

“Wood is the most important material for the instruments. I use fir wood from the Caucasian forests as the structure and look is quite similar to the one that classic Italian luthiers used. The wood is crucial for the violin’s sound: fir wood makes a clear sound,” he explains. “Every single violin I made using that wood had a gorgeous sound, a unique timbre. But craftsmanship and skill is fundamental.”

Martin Yeritsyan always makes several instruments at the same time. “When I start making violins, it is either three, five, or seven at once – always with odd numbers. I only work on one specific instrument when there is a special order. And I always test my instruments,” he says. “My friend, a famous violinist Jean Ter-Merguerian used to test my instruments, too. If it has a decent quality, then I can offer it. I never offer it to anybody, until it is perfect.”

The first critic of the master is the master himself.

Before the collapse of the USSR, Yeritsyan used to make instruments for the Moscow State Collection of the Musical Instruments for the Astrakhan Conservatory. He says that during the state exams in the Astrakhan Conservatory, the jury members were always surprised by the wonderful sound of his violins.

“I am proud that people like my instruments. I am the adherent of my father’s school of violin making. Thank God, my two sons, one in Spain, the other in Armenia, are also violin makers,” he says.

Professor Yeritsyan’s instruments today are valued at about $4000-5000 US and he has orders from all over the world. He says, however, that it is the age of the instrument that dictates its value.

“My father’s instruments are much more expensive now than when he was alive, similar to Stradivari who would sell his instruments for three gold coins, but now they are valued at millions of dollars. Time needs to pass for people to seek my instruments,” he says.

Yeritsyan not only knows the exact number of instruments he has made during his lifetime, he remembers every single detail about each instrument.

“I have several notebooks where I record all the details about every single instrument. I note the type of wood, its origin, the future owner of the instrument, the details about the sounding board [the upper and lower surfaces of the violin]. Taking into account all the information in my notebooks, I have made about 300 violins, 100-150 violas, 39 cellos and other instruments,” he says.

Yeritsyan has also created a unique model of an Armenian national instrument. Grigor Arakelyan, a musician who currently plays that instrument, suggested calling it an Armenian viola. It is a slightly bigger than a viola but smaller than a cello and has a unique structure and timbre.

“Once I was at a concert, and one of the musicians was playing an Armenian melody on the kamancha. It was not pleasant to my ear, the sound of the kamancha cannot reveal a true Armenian melody,” he says. This served as the inspiration to create his Armenian viola: “I decided to create a new type of Armenian national instrument, so that people play it instead of the kamancha and we can hear the impressive and pleasant sound of Armenian melodies.”

Martin Yeristsyan says the sound of the instrument is what attracts people. “I prefer an instrument that might not be beautiful with a stunning sound than a beautiful instrument with a poor sound,” he explains. “The audience sitting 8-10 meters away from the stage will prefer to listen to the sound than look at the instrument.” The master luthier explains that if an instrument is made correctly, it will eventually sound better and better. “Time has an impact on the instruments’ timbre and sound,” he says.

Many people want to learn the art of violin making, but Yeritsyan will not share family secrets with the others.

“I have sons and a grandson who will continue this tradition and knowledge we have from my father… This is a family thing, and it needs to be transfered from generation to generation,” he says. “The same practice exists in Italy; Stradivari’s sons continued his art…I have my secrets indeed.”

Yeritsyan says that when he refused to reveal the type of varnish he uses for his violins to an Italian master, he wasn’t offended because the master understood the tradition. “I told him it’s a family secret. My sons are the only ones who know that,” he says.

Yeritsyan labels every instrument using the old European tradition. The language of the label is Latin: “I write ‘Martin Yeritsyan, Son of Shahen, Yerevan, the year.’ You can read the label from the F hole.”

The mysterious and mystical sounds of the violin, made by the hands of a master luthier, trained by a father who experienced loss and calamity but embarked on a journey of beauty and creation can be seen, heard and felt in this small room in the basement of the Aram Khachaturian House-Museum in the capital of modern day Armenia. A room full of different types of wood, various tools and musical instruments in different stages of construction. And while your senses are overtaken by the smell of wood and glue, the wrinkled hands of Martin Yeritsyan, the oldest violin maker in Armenia, continue to carve and scrape the upper surface of a future violin.

As he sits on his table working, Martin looks up and says, “I don’t have an honorary title but I think my instruments are the biggest contribution to my nation.”