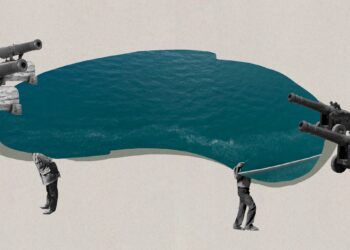

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

While concrete numbers are still hard to come by, an estimated 80,000 Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian nationals have moved to Armenia since Russia began its invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Aside from many ethnic Armenians, who may or may not hold an Armenian passport, returning home, it’s clear that highly-educated, middle-class ethnic Slavs with no prior links to their new home in the Caucasus make up the bulk of these arrivals. No prior links, that is, aside from a historical precedent as a place of exile for generations upon generations of Russians fleeing repression under the Tsars, and then later General Secretaries. A tradition which yet another generation of young, free-thinking Russian journalists, programmers, graphic designers, marketing managers, artists and scholars live up to as they rebuild lives in Armenia.

The sheer size of the legions of tall, straw-haired people converging on Yerevan at once, carry-on luggage in tow, searching for their AirBnB booking or a decent cappuccino, has triggered, among some Armenians, unsettling memories of the Red Army’s capture of the city a century earlier. If concerns over cultural or linguistic dilution, among other things, are not totally unfounded, it’s worth pointing out that Yerevan has hosted successions of Russian emigre communities for quite a long time now.

Indeed, the current number of recent arrivals, even if we exclude those who are likely ethnic Armenian repatriates, are comparable to those of Slavs who called Armenia home as recently as the 1980s. According to the 1979 Soviet Census, 70,000 Russians, 9,000 Ukrainians and 1,100 Belarusians lived in Soviet Armenia. Despite outmigration in the years following the collapse of the USSR, at least 12,000 of them remain to this day. But the history of slavic emigres in Armenia is at least as long as that of Russia’s presence in the region, with successive groups of slavic-speakers fleeing religious persecution, intellectual repression or entrepreneurial limitations, finding in this remote periphery of Empire, the freedom and community support to explore their creed, scientific research or business ambitions.

The first Russians to settle in Armenia began to arrive even before imperial troops did. In the first decades of the 19th century, members of a Russian religious sect, known to their detractors as “Molokans” or “Dairy-eaters” due to their practice of consuming dairy even during Lent, settled in the mountains of Lori and Tavush regions, as far away as they could get from the reach of the Russian Orthodox Church. There, they founded several villages, where they engaged in animal husbandry, agriculture and trades. Often compared to the Amish due to their commitment to pacifism and rejection of modern conveniences, the Molokans have garnered the respect and friendship of their Armenian neighbors, who have come to praise their diligent work ethic. Encouraged by a “live-and-let-live” policy of religious tolerance practiced by successive Armenian Governments, the Molokans, forgotten in the highlands of Lori, continued to prosper despite Soviet terror and the chaos of post-communist liberalization, with 5,000 of their descendants living there to this day.

But victims of religious persecutions were not the only Slavs to settle in northern Armenia at the turn of the 19th century. As the Molokans were sowing their first harvests, nearby villages like Petrovka, Pushkino and Nikolayevka were being settled by colonists of a different sort: political exiles. Indeed, as part of a policy of pacifying the newly-conquered expanses of the Russian Empire, Tsar Alexander encouraged the settlement of ethnic Russians in far-flung provinces like the South Caucasus. Though, in practice, these peripheries were also a convenient place to dump people which the Empire deemed politically too dangerous to keep in or around Saint Petersburg. While most descendants of these Russian exiles have either integrated into the local population or since left, their impact can be felt through numerous physical traces scattered across northern Armenia, including intricately carved wooden cottages and beautifully decorated Russian Orthodox churches.

One such church, the timber and mortar St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker, in Amrakits, Lori, attests to a long history of slavic settlement in the region, originally having been built by Ukrainian Cossacks, only having been abandoned after the 1988 Shirak Earthquake.

Regardless, with the arrival of the Red Army in November 1920, the newly-formed Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia, assembled from the remnants of the First Republic, a generational changing of the guard took place among Russian exiles. This time around, it was the dissenting soviet intellectual.

In many ways, Armenia’s modern status as a post-Soviet Silicon Valley owes its status to the arrival of these people in large numbers starting in the 1920s, and then picking up pace as World War II raged across Europe. Far from the front lines, Soviet Armenia proved a strategically significant weapons development and manufacturing center during the war, attracting thousands of displaced scientists from across the USSR. Mirroring, strangely enough, its counterpart in the Bay Area, state funding for the armament industry eventually hatched a burgeoning indigenous high technology scene in the post-war years.

Yet again, Armenia’s peripheral location made it a uniquely attractive destination for some of the Soviet Union’s best and brightest scientific minds who, born to politically suspect families or due to discrimination against Jews, found their career trajectories hitting a glass ceiling in the prestigious institutes of Moscow and Leningrad. Far from the centers of power, and thus surveillance, in Moscow, these highly-skilled, Russian-speaking misfits were free to explore their academic pursuits, in the process helping to lay the foundations of Armenia’s semiconductor manufacturing base and scientific research, which lay the foundation for its modern IT industry.

The arrival of a new generation of young, free-thinking and technically-skilled Russian emigres presents an interesting parallel, and also a taste of things to come. As so many of them get gobbled up almost instantly upon arrival by the burgeoning, yet chronically under-staffed tech sector that their predecessors helped kick-off a generation ago, it is tempting to wonder what sort of lasting contributions we can expect to see as Armenia provides these new arrivals with security, respect and the freedom to create.

Also read

Armenian Attitudes Toward Work and the Soviet Legacy

The popular opinion about the hardworking nature of Armenians changed after independence, when Armenia was left to become the master of its own destiny. Mikayel Yalanuzyan examines the Armenian work ethic.

Read moreArmenians in Lviv Emboldened to Stay

As Ukraine’s western city comes under Russian missile attack, the Armenian community is wrapping its treasures, but preparing to stay.

Read moreRusso-Turkish Wars Through History

This new series presents the Russo-Turkish wars of the 19th-20th centuries, which were of crucial importance for the two segments—eastern and western—of the Armenian people.

Read more

New emigres can help advance Armenian science and technology. They may not stay very long in Armenia but they are likely to remember how Armenia accepted them. Academician Yuri Orlov worked at the Yerevan Physics Institute in the late 1960s. He later spoke on behalf of Karabakh Armenians.