There is unusual activity in the cafeteria of one of the small hotels in Yerevan. It is dinner time and the tables are packed with dozens of children around them, four per table. With their forks and spoons they are moving their food around in their plates, pushing it aside. No one has an appetite, their relatives don’t have food.

“Eat, eat,” says Mrs. Anahit as she walks by the tables, almost pleading. “Eat so that at least I don’t have to worry about you.”

The teacher-turned-mother to 14 children overnight does not have the heart to reprimand any of them, in the evenings especially, when they feel how much they miss their mothers and all their hearts become a little more fragile. They are all, without exception, immersed in scrolling the news, maybe there is good news from home.

Mrs. Anahit tries to disperse the chilling thoughts, calling this ordeal, this test overwhelming for the children, an adventure. “It is like in the movie Home Alone, only that they are not home but yet, they are alone.”

Through Mountains, Valleys and Non-Existent Roads: Anahit Goes Home

After the 2020 Artsakh War, Anahit Gabuzyan, the choir and music teacher at the Stepanakert Youth Creative Center had made a promise to herself to never leave Artsakh. An inexplicable and anxious voice would constantly tell her that without her the house would go to ruin, if she set foot outside of Artsakh, she won’t come back.

“When the principal said that I would need to take the children to Yerevan for Junior Eurovision, I refused. I said I could not, because my long awaited newborn first grandchild would not stay without me, that my daughter-in-law needed me. The principal said it was only for a day, they will be fine without me and that I won’t even notice their absence,” Mrs. Anahit recalls.

In the car, on the way to Yerevan, the children were happy that they were chosen to go on this trip. They were the lucky ones. Mrs. Anahit was internally suppressing her anxiety, telling herself, “It is only a day, you’ll be home tomorrow.”

They had a day off after the Junior Eurovision song contest. They were already in the car on their way back when they learned that the road was closed. When they returned to Yerevan, they did not upback their bags, it was going to be a day or two, maybe three… It took a while before they dared to admit to one another that maybe it was going to be longer. They needed to stay strong.

“We had to explain to the kids that they had to go to school in Yerevan,” Mrs. Anahit says. “At first they would not be swayed and then they resisted. It was the same story over again every evening. One would say their back was hurting, the other’s throat would hurt, the third’s leg. They would come up with any excuse not to go. But convincing me is a hard task. Their education is very important, also for their parents’ peace of mind. I spent 20 minutes each morning knocking on everyone’s doors, waking them up to send them off to school.” Waking them up was especially difficult, says Anahit, because the children would barely sleep and were “constantly talking about the road and Stepanakert.”

Waking up at 7:30 each morning was difficult for Mrs. Anahit as well, she had not slept for 47 days, save a couple of hours around dawn and each night it would be the same dream… going home through mountains, valleys and roads that did not exist.

“These were not roads I’d ever been on, I’m not even sure if such roads exist but I would run away from Yerevan every night and reach Stepanakert through those footpaths, go knocking at my students’ doors asking them not to skip class even if I’m not there. Then all of a sudden I would remember that the kids are back in Yerevan, that they would not wake up if I’m not there and I would run back.”

The children were doing well at school. Anahit even managed to go to a parent-teacher meeting. All the teachers were praising the children from Artsakh, saying they were not only smart but also mature, too mature for their age. Mature and sad.

For 47 days, Anahit saw her newborn grandchild a few minutes each day, when there was electricity and Internet connection in Stepanakert. Her daughter-in-law would cry every time they spoke but also put her mind at ease, saying they had everything they needed at home, no need to worry.

“I only know that the people of Artsakh are solid and strong. There is so much blood in our land, precious blood, my brother’s blood. None of those lives were one too many for this world. How do you abandon your home after all that, how can you say enough, too much, too hard? It has been difficult, it is not going to be easy but that is our burden to bear,” says Mrs. Anahit and admits that she is tired and exhausted but she does not have the right to be weak. The children need her to be strong, at least for that one day when they are on their way back home.

Inessa: I’m Not Afraid, I’m Not Scared of Anything

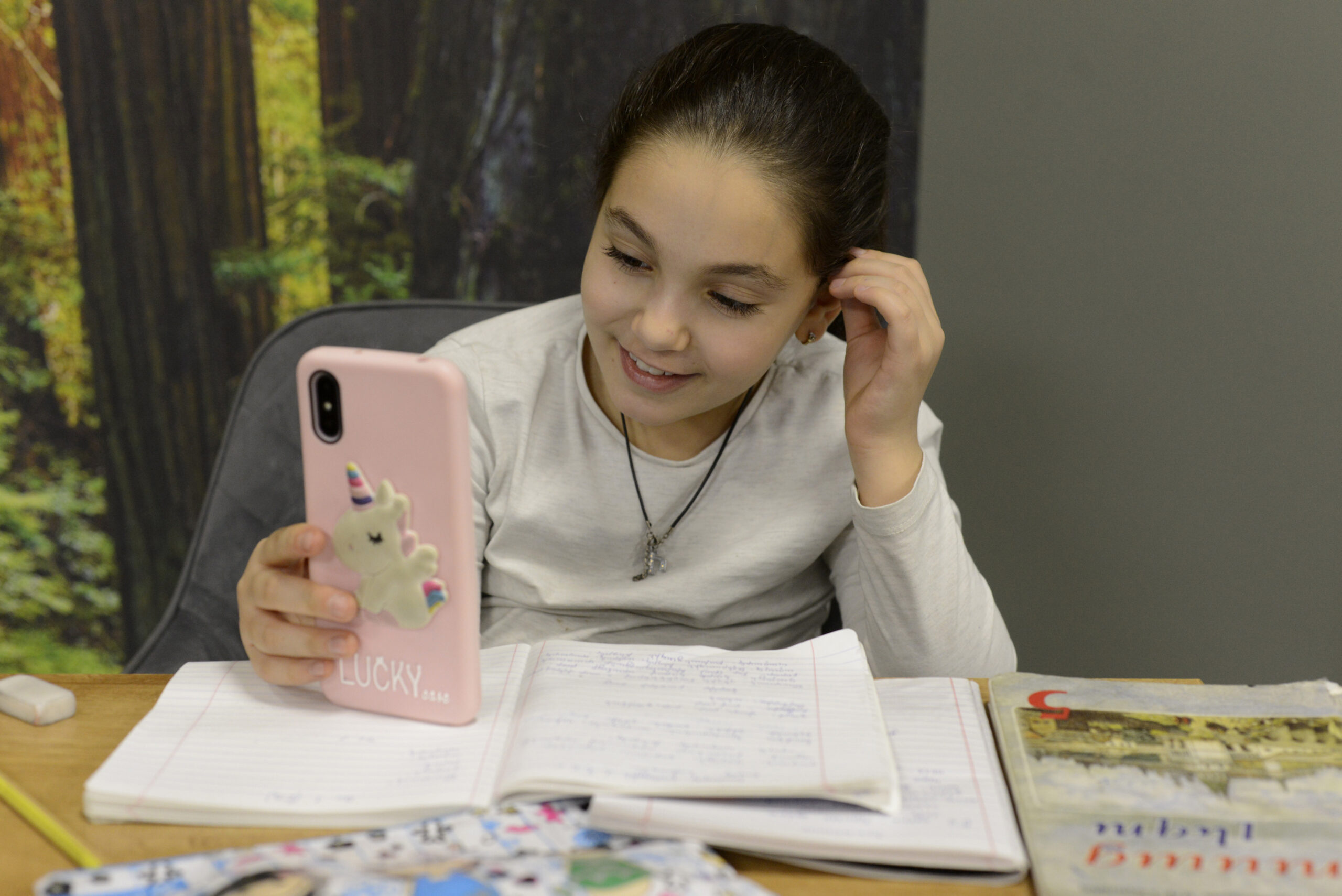

The youngest in the group is 10-year-old Inessa Grigoryan. The youngest and the most loved. She has a book and some notebooks on the table. She is doing her homework for tomorrow. The phone is right in front of her as well, her mom is making sure she is doing her homework from hundreds of kilometers away. The older children come by, one-by-one, offering to help, but Inessa is already done.

“I’m going to school in Yerevan, but I do not like it much,” Inessa says. “All the teachers back in Stepanakert knew which subjects I was good at and which ones I was not good at. Today, here, my teacher reprimanded me, I was upset. She came up to me and asked in front of everyone why I was not doing the assignment. But I had already finished it long before everyone else. I do not like it when they reprimand me, especially when it is not fair.”

On that day, Inessa’s mother had gone to her school in Stepanakert to pick up yet another certificate praising Inessa, this one was for her recital of a poem written by her grandfather. She shows the picture her mom has sent to everyone and says she will see it herself once she gets home, but until then, it is making her parents proud.

Inessa has never been this far away from her mother, and even though all she wants is to hug her mother, she is also sometimes frustrated; her mom is calling her way too often.

“She misses me a lot and I miss her. She still can’t believe that we are going home. And I keep saying that whatever happens, I’ll be home in February for my brother’s birthday. Whatever happens, even if the world is upside down, I will get home. If they do not allow it, I’ll walk, I’m not afraid of the Turks or the road. That is our home, what is there to be afraid of? I’m not scared of anything,” says Inessa.

And even though they have been promised that they will be home tomorrow, Inessa has done all her homework and has prepared her outfit for school because she knows that there is the possibility that they might have to turn back. She knows she needs to be ready for everything, she needs to be strong, so what if she is small.

“The kids are afraid that the Azerbaijani’s will stop our car as well, that they will film us too. I’m just concerned that my mom will see the video and get worried, other than that, I’m not afraid. If they stop our car, I’ll say Karabakh bizimdir*, Shushi bizimdir. Let them know that it is ours,” says Inessa.

She knows that what is hers will always be hers. Even if things are very complicated right now, even if they send them back. She is strong and can wait a little longer. The important thing is for her mom not to be too worried.

Vladimir: Let Me Be Hungry, Be Thirsty, Be Cold.. But at Home

Vladimir Galstyan or Vovka, as people who know him call him, is the only one who is keeping away from the group and is not taking part in the game. He is counting the minutes until 10 p.m. when the electricity comes back on in Stepanakert and he can finally talk to his mother.

Vovka, 13, is scrolling through social media and sighing every once in a while. Anahit is again worried. The child is going to have a high temperature this night as well, that is always the case when he misses his mother a lot.

“My family is not telling me anything but I know everything. I read, I know that there is no food and there is no electricity, no gas. Sitting here all day I think about my family, I wonder how they are holding up, what they are doing, are they hungry? I don’t know, it is very difficult,” Vovka says, his words a pile of sentiments not suitable coming out of the mouth of a child.

When he left Artsakh to come to Yerevan, Vovka had packed a day’s change of clothes in a bag. Today, he is packing a big suitcase full of 47 days-worth of clothes, toys and stationary. He is the only one who is not in a hurry. For 47 days, every evening before bed, he has packed his things as if he was heading home.

“I’m ready to go home any minute, every second. Last week, when the children from Goris went to Artsakh I was very happy for them but also I was very sad that I was not with them, that they went home without me,” says Vovka.

***

In a few minutes, Vovka will get to tell his mother that he is finally coming home. Then the hardest part will come, the wait until morning. He has missed his mom and his piano the most. He knows it is going to be difficult in Artsakh but it is all the same, he is ready to endure hunger, thirst or cold so long as he is home with his parents.

“This was my first New Year away from my family, I was very sad. We had written a letter to Santa asking for gifts, but we did not get gifts that night. We had given up on the gifts but then on January 13, they arrived. I understood that a person should learn to wait, to persist as difficult as it is. One day the road will also open, hopefully tomorrow, and we will finally get home,” says Vovka as he packs his new toy model kit that he received as a gift in Yerevan.

Return

On January 27, 2023, the children from Artsakh, including Inessa and Vovka, separated from their families for 47 days, returned home accompanied by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Russian peacekeepers.

*Is ours in Turkish and Azerbaijani