In recent months, European politicians and analysts have been expressing cautious optimism in private around the possibility of the end of Russian influence in Armenia. Europe’s interest in Armenia is undeniably on the rise, driven by recent developments in the region, and encouraged by the country’s apparent pro-Western and anti-Russian signals.

At a recent meeting at a Berlin think tank, a staffer told me how great it was that Armenia could finally break free from its dependence on Russia. “Moldova was in the same situation and managed to get out from under Russian control,” she asserted. Her implication was clear: the possibility exists, it’s just a matter of making the choice.

Back in Armenia, however, the presence of Russian officers at Zvartnots Airport and the sight of Russian peacekeepers’ armored vehicles on Armenia’s southern roads, even after their complicity in the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh, present a stark contrast to the notion of swift liberation from Russian influence.

Quo Vadis Armenia?

European optimism around Armenia’s shift makes sense at first glance. In the past year, Armenia has taken several significant steps to deepen relations with the West. It welcomed an EU border monitoring mission to its territory, took part in military training exercises with U.S. troops in Armenia, and signed an arms deal with France. Armenia has also begun publicly expressing dissatisfaction with Russia. In recent months, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan underscored that Armenia could no longer rely on Russia and that he saw no advantages in the presence of Russian soldiers on Armenian soil.

Until recently, relations between Armenia and Russia had remained relatively stable, even following Armenia’s democratic revolution in 2018. Contrary to certain predictions, Moscow exhibited a largely indifferent stance towards Armenia’s democratic choice, as its own interests were not significantly threatened. Pashinyan’s government took pains to signal its amiability to Russia, even deploying troops to Kazakhstan in January 2022 as part of a Russian-led CSTO-wide response to help suppress anti-government protests. This commitment was made despite the CSTO’s refusal to defend Armenia during Azerbaijani incursions into Armenia in 2021.

The Emerging Divide

Armenia’s political relations with Russia really began to deteriorate in the aftermath of Azerbaijan’s attack on Armenia in September 2022. This event marked a turning point for Yerevan, following a series of upsets involving the Russian peacekeeping contingent, most notably its acquiescence to the Azerbaijani capture of the village of Parukh in March 2022. Together, these incidents demonstrated that Russia was incapable or unwilling to fulfill its promised security assurances. Russia’s losses in Kharkiv, Ukraine during that period further highlighted its vulnerability, reinforcing the belief in Yerevan that Russia could not ensure security.

The worsening relations only accelerated after Azerbaijan’s attacks on Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023, which culminated in the complete ethnic cleansing of the territory––a horrifying and region-altering situation Russian peacekeepers were stationed to prevent. Compounding the sense of Russian complicity, local reports indicated that Russian peacekeepers withdrew from their positions just before the assault. To aggravate the situation further, leaked information revealed that the Kremlin had directed Russian state media to assign blame for the assault to Armenia.

For decades, Armenia’s relations with Russia have been built on the necessity of countering the security threat posed by Azerbaijan. But, with Nagorno-Karabakh now fallen and depopulated, coupled with Russia’s duplicit tolerance of Azerbaijani aggression on Armenia and its confrontational rhetoric towards Yerevan, Russia’s role has shifted from being merely impotent to hostile.

Despite this, Europeans’ apparent desire for Armenia to sever ties with Russia and fully embrace the West is unrealistic. Such a shift is unfeasible in the short-term, or at the very least, not without considerable pain and unpredictable risks, especially at an extremely vulnerable time for Armenian sovereignty.

A One-sided Entanglement

Armenia’s deep-rooted structural dependencies on Russia persist and, in some cases, are deepening further, even amid the escalating anti-Russian rhetoric in Armenia.

In trade, Armenia has never been more reliant on Russia. In 2022, bilateral trade nearly doubled to $5.3 billion. Armenian exports to Russia nearly tripled from $850 million in 2021 to $2.4 billion in 2022, now constituting 51% of Armenia’s total exports. Imports from Russia also rose this year, increasing by 151% to $2.87 billion.

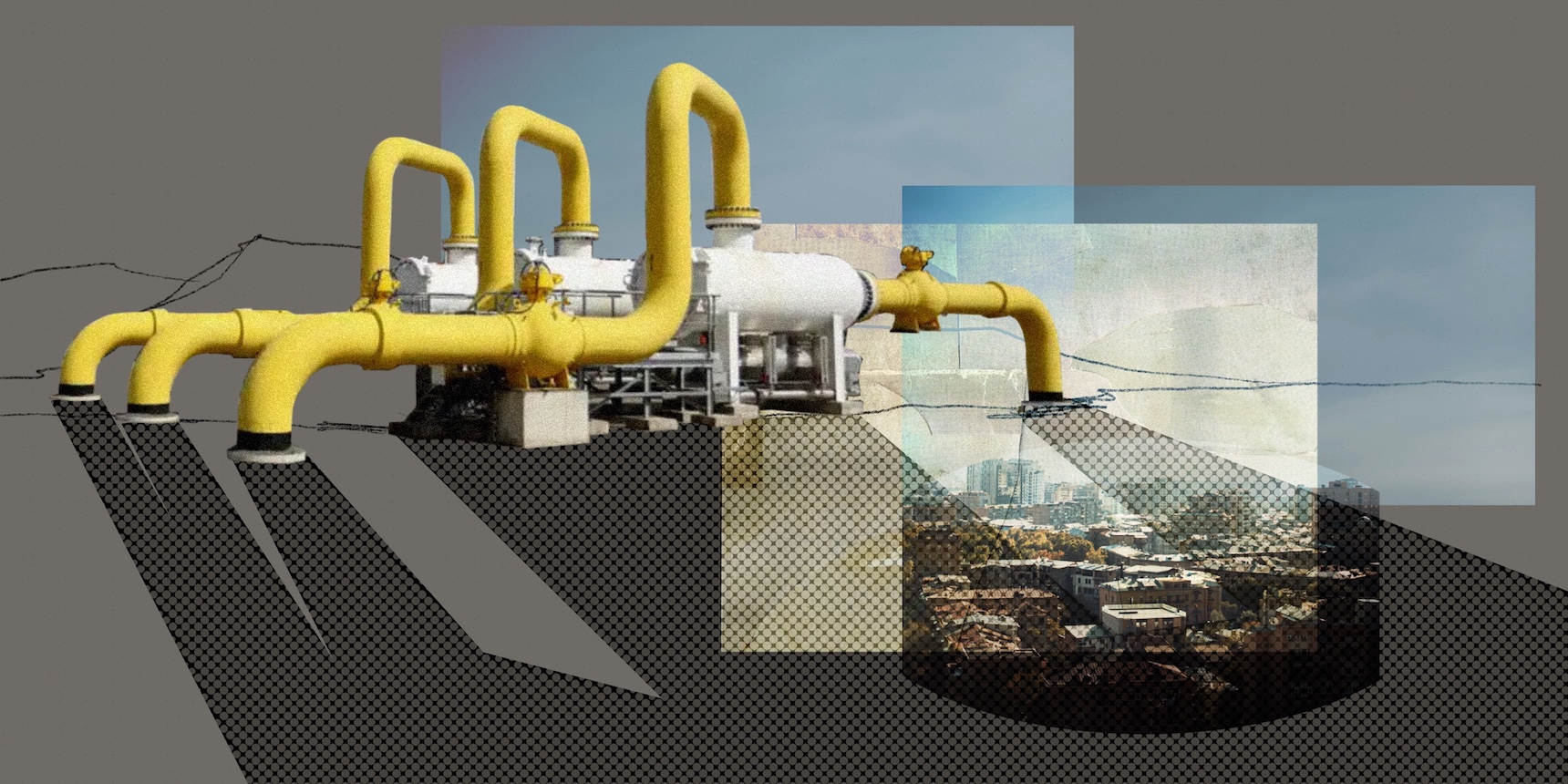

This dependence extends to vital energy resources and other key sectors, with Russia providing approximately 70% of Armenia’s petroleum oils and almost 85% of its natural gas. Russia controls critical infrastructure in Armenia, including the gas distribution network, the Iran-gas pipeline, and a unit of the Hrazdan Thermal Power Plant (TPP). Russian control over specific areas is expanding, exemplified by Armenia granting permission this year to the Eurasian Development Bank to finance the Amulsar Mine.

These dependencies on an unreliable and often hostile power pose a significant vulnerability for Armenia, further exacerbated by the ongoing security threat from Azerbaijan, the absence of effective deterrents against potential renewed aggression, and the lack of concrete security guarantees from any external power. It’s essential to acknowledge that Armenia is not Moldova.

European partners must recognize that without addressing Armenia’s deep structural dependencies on Russia and providing concrete security and economic guarantees, expecting a significant foreign policy shift towards the West is unrealistic. This understanding is crucial, especially as the West becomes more engaged in Armenian affairs.

In Armenia’s context, countering existential threats takes precedence over whatever grander geopolitical choice that Europeans think Armenia should be making.

Also see

Russia in the 19th Century: A Sketch of an Empire in Transformation

Although Russia viewed itself as a European power throughout much of the 19th century, it had to turn eastward due to its distinctive geography and socio-economic dynamics. This article embarks on a journey through 19th-century Russian history culminating with the 1917 October Revolution.

Read moreTsardom and Empire: The Formation of Russian Imperial Ideology

Can Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its weaponization of the Orthodox faith and Putin's references to Peter the Great and his campaigns indicate historical precedents for Russia's re-emerging imperialism?

Read moreRussia, Turkey, China and Iran: The Return of Empire

Once thought to be a problem solved by the collapse of empires in 1918, and of colonialism in the 1950s and 1960s, the concept of Empire has been resurfacing recently, propelling the world toward a model of domination.

Read more