The storks soaring above the village of Ranchpar in Armenia occasionally descend to their nests, woven atop electricity poles. For the people of Artsakh who were forcibly displaced as a result of the wars and have found refuge in the village, storks hold a special significance.

Ranchpar village is located about ten kilometers from the city of Masis in Ararat region. Forty-two-year-old Rita Baghdasaryan’s large family is one of the many Artsakh families who have taken refuge in Ranchpar. This is the second time that Rita has been displaced.

The demographic composition of Ranchpar was not always mono-ethnic. Azerbaijanis also lived here, before relocating to Azerbaijan at the start of the Karabakh movement. Similarly, many Armenians living in Azerbaijan migrated to Armenia. At the start of the movement, displaced Artsakh Armenians from Baku and Gandzak largely settled in Ranchpar. Later, a large number of Artsakh Armenians relocated to the village after the Artsakh wars of 2020 and 2023, joining their relatives who had settled there earlier.

Rita has experienced four wars in her lifetime. “We have lost a relative in every war,” she explains. “My father was killed in the first war, my ailing mother was killed in the village during the 44-day war by the Turks [meaning Azerbaijanis], and my brother was killed in this recent war.” However, this most recent war was the most horrific. “My entire family was fighting in the war. There was no means of communication, and we had no information from anyone,” Rita recalls, specifically referring to her son who was in the military. His unit had been surrounded for five days, and they had no information about him.

Rita, a mother of six, had additional concerns. Three of her children were at school when the bombing started, and due to a lack of communication, they were unaccounted for several hours.

During the 2020 war, the Baghdasaryans lost their home in Hadrut and had to rent a place in Stepanakert. But this war had a much more traumatic impact. “We had already lost our home, but at least we were on our own land,” says Rita’s husband Beglar. “If there’s an opportunity, I’d go back right now, but only if we don’t live with Turks. After so many losses, it’s impossible.”

The family is attempting to renovate the dilapidated house on their own, even though they rented it at a high price. They have received some funds from the government, which they are using to address the issue of hot water. However, the house lacks essential household appliances.

“Although many arrived in large vehicles, they chose to bring their neighbors and relatives instead of their belongings. As a result, practically everyone is in need of mattresses, blankets, and household appliances. We are trying to acquire these items through benefactors, friends, locals, and the municipality, and distribute them systematically,” says Vahan Vardanyan, the head of the community. According to Vardanyan, 356 people (108 families) have sought refuge in the village following the recent Azerbaijani onslaught. The village school has 54 pupils, and there are 25 toddlers attending the kindergarten.

“Moreover, 108 people settled in the village following the 2020 war. They also require assistance, but the current priority is to assist those who have been forcibly displaced due to the recent violence instigated by Azerbaijan,” says Vardanyan, adding that providing aid alone isn’t sufficient. “We must find employment for our forcibly displaced compatriots.”

The Baghdasaryan’s son, who miraculously survived the war, has made the decision to leave the military and work in a bakery. He reached this decision during the blockade, when there was a shortage of bread. He already has almost a year of experience in this work. The community, however, doesn’t have a bread factory.

The father expresses hope, saying, “If we receive support, maybe one day we will have our own factory where the entire family can work. This will also allow us to build a house and finally get my son married.” This dream keeps the Baghdasaryans, who have lost their home twice and are starting a new life from scratch, going.

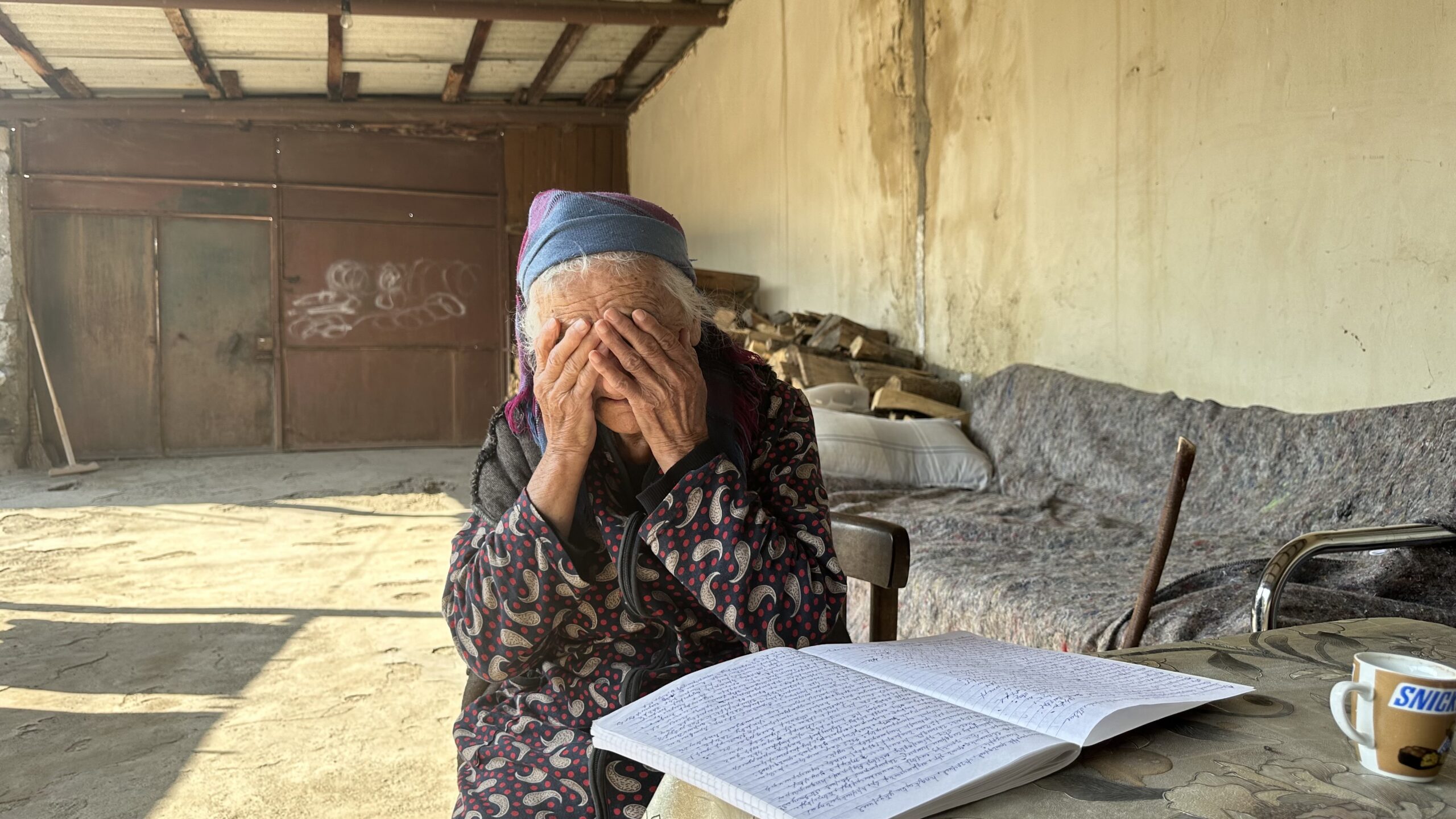

Greta Vardanyan, 80, also found refuge in Ranchpar after the 2020 war, having moved from the village of Hin Tagher in Hadrut.

Greta lives with her husband and her in-law Karine Shadyan. Despite residing in this village for three years, they still have numerous unresolved issues, and new ones have also emerged. Due to Azerbaijan’s recent aggression and the loss of Artsakh, they are unable to receive their pension, which is the only means of paying the already inflated rent.

“I worked as a teacher in the village my entire life, and now they don’t even give me a pension. How am I going to live?” asks Greta. Recalling the memory of leaving their homeland, which she had never left before, is very difficult for her. She turns to poet Avetik Isahakyan to express her longing and sorrow: “They took away my beloved Artsakh, they wounded me and took it away. What a wicked world this is. They tore it out, they took away my heart. I loved my village, my homeland, my paradise Hadrut.”

Greta attempted to document the war by keeping a diary. “We were living peacefully; September is harvest month, and we were preparing for winter. We had collected tons of potatoes, beans, honey, and home-grown vegetables, but there was still a lot of produce left to pick in the vegetable gardens, which remained unharvested.”

Karen Sargsyan’s family, consisting of his wife, six children, and mother-in-law, was forcibly displaced from Kolkhozashen and found refuge in Ranchpar. They currently pay 120 thousand drams each month to rent a dilapidated house. Karen is unable to work due to his disability. His wife is the sole breadwinner of the household, working at a local fish farm where wages are paid per diem.

“We left the door open and departed in the neighbor’s truck,” Karen’s wife recalled. “We didn’t bring anything with us, except for my son’s documents who was injured during the war. We burned everything, including his military uniforms and medals, because I was scared they would harm my son if they found him.”

The house where they live doesn’t have a bathroom. They are in need of various essentials, including a washing machine, a refrigerator and bedding. Karen speaks with great respect about a neighbor who selflessly left his belongings behind in order to transport his fellow compatriots, including themselves. The five-day forced exodus from Kolkhozashen to Ranchpar was particularly challenging. They spent the night in the vehicle in Stepanakert, then endured a three-day drive to Goris, and finally arrived in Ranchpar, where their relatives had settled in the 1990s. Karen has lost all hope of returning to his homeland. Not even promises of security guarantees from the international community or any other entity can entice him to return to Artsakh. “I can hardly believe that I was able to save my children. Of course, if all the people of Artsakh return, I will too. But for now, that seems impossible,” says the father of six.

During the 2020 war, 28-year-old Lilit Aghabekyan’s family was also displaced from Hadrut and relocated to Ranchpar. They have four children.

The family relies solely on their greenhouses for income, but they are in poor condition and need repairs. The family does not have the financial means to fix them. They also do not receive any child benefits for their children. In an effort to find another source of income, Lilit and her mother-in-law make the famous Hadrut pickle. “Everything is different here. Even the fruit tastes different,” says Lilit.

Lilit shares that her children still carry the trauma of war. “Three years have passed, but they haven’t forgotten the scenes of war. I can only imagine what those who experienced the nine-month blockade, the latest war, and deportation have been through,” says Lilit. She thinks out loud, “Maybe it was a good thing that we left earlier.”

The image of Dizapait’s Kataro Monastery is hanging on the wall of the rented house. Kataro was considered the symbol of Hadrut. “We wanted to have a piece of Hadrut in our house, which is why we hung it,” says Lilit. She is still struggling to cope with the loss of her native Hadrut, as well as the whole of Artsakh. “Our thoughts are always in Hadrut, every single day. No matter how good it may be here, our home is there.”

Storks soar above the sky of Ranchpar village. There were no storks in Tomi, Hin Tagher, and Kolkhozashen. The displaced Artsakh Armenians, however, hope that like storks, they too will one day return to their homeland –– to Artsakh.