Listen to the article.

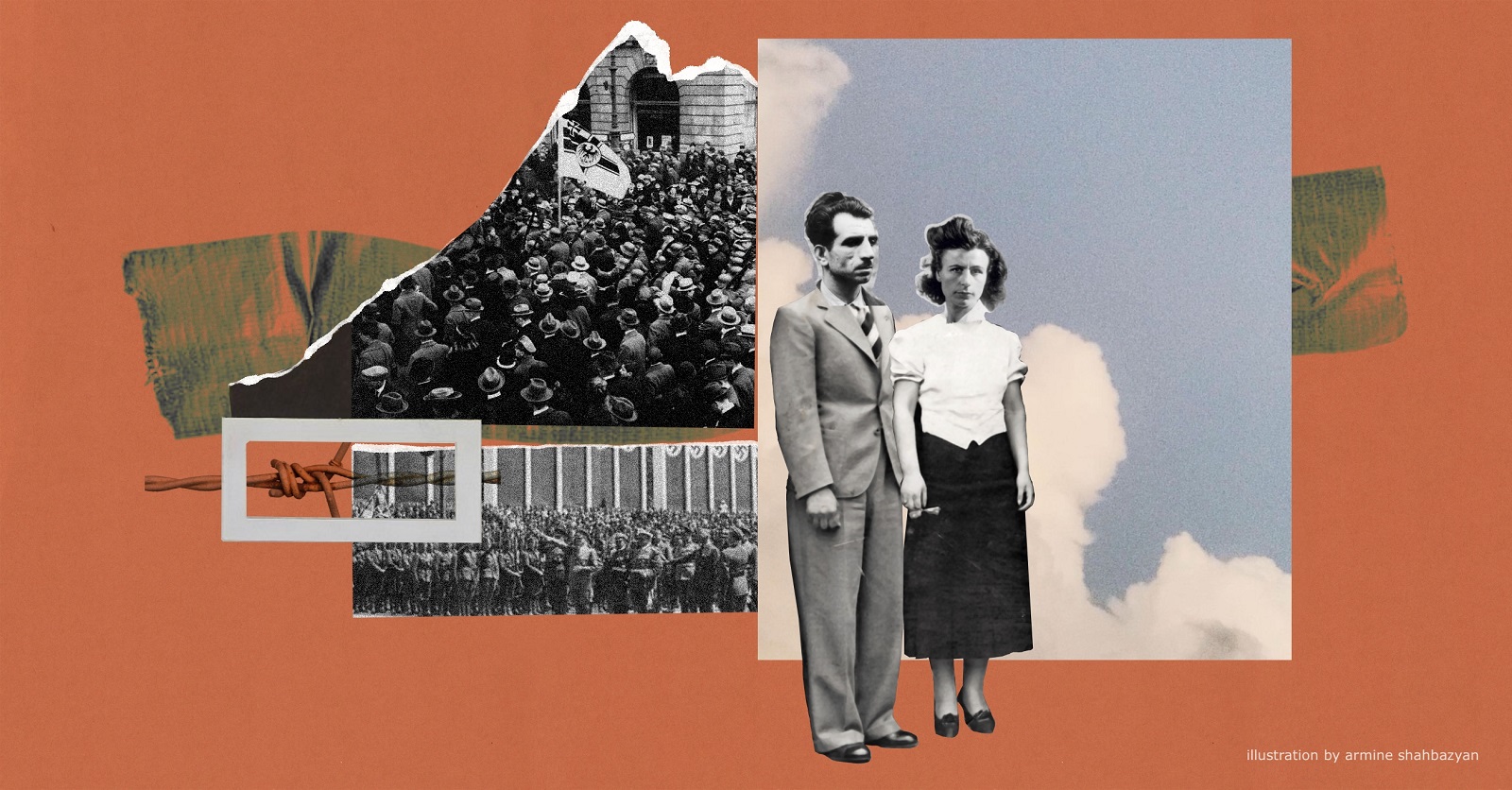

July 1939: Missak and Melinee Manouchian attend the 150th anniversary celebration of the French Revolution in Paris. The recent victory of fascism in Spain, only two months prior, weighed heavily on their minds. Missak proudly marched with the French flag, accompanied by Melinee. Together, they extolled the virtues of the revolution and its impact on the Armenians who sparked the national liberation movement of the 19th century. Somewhere between daydreaming and embracing the urgency of the times, Missak states:

“The atmosphere is dark, we are entering a period of confrontations. Our generation will have to fight against Nazism. This might be terrible but we will emerge victorious.”[1]

Generations of Armenian revolutionaries have participated in various forms of resistance, from peasant rebellions in the distant, rugged provinces of the Ottoman Empire, to languishing in Uruguayan prisons, and training alongside Palestinian militants in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. Their involvement extended beyond active militancy to printing and transporting literature, raising funds for imprisoned comrades, and providing safehouses for fugitives –– acts of resistance undertaken by ordinary Armenians. Driven by a range of beliefs, from national liberation to opposition against fascism, these rebel spirits are not household names; but rather quietly discussed in the tales of elders or mentioned in the footnotes of historians.

Earlier this year, Missak and Melinee Manouchian entered the French Pantheon for their role in the fight against Nazism. The ceremony was a visual spectacle that attracted over three million viewers in France, in addition to thousands of views from various livestreams on YouTube. This event not only signifies a new phase in Franco-Armenian relations, but also marks a high point in the decades-long efforts to gain recognition for the members of the Francs-tireurs et partisans – main-d’œuvre immigrée (FTP-MOI), a subgroup of the Francs-tireurs et partisans (FTP), a wing of the French Resistance composed mostly of foreigners. This significant task has been carried out by a group of veterans, their family members, and supporters. The first time foreigners have been inducted thus becomes the culmination of this project and a major acknowledgement of the role of foreigners like Missak Manouchian in French history.

Towards France [2]

The calamitous trio of revolution, genocide, and war in the early 20th century led to unprecedented levels of immigration to France. The diverse ethnic composition of the FTP-MOI can be traced directly back to the precarious circumstances people faced. These included Italians fleeing fascism, Polish Jews facing anti-Semitism, and Armenian refugees such as Missak who was orphaned by the genocide at an early age.

Missak was raised in the orphanages of Lebanon, then under French control. There, he was first introduced to the French language and literature. Part of the wave of immigrants needed in France at the time, he eventually settled in Paris. In the city, he took up factory work and odd jobs, while also participating in the literary circles of the Armenian diaspora.

In 1934, Missak joined the HOK (Armenian Relief Committee-Հայաստանի օգնության կոմիտե), which essentially served as a front for the Communist Party across the diaspora. The organization arranged dinners and balls for fundraising. As orphans trying to rebuild their lives in exile, Melinee and Missak began their relationship as members of HOK.

To the Barricades

The Spanish Civil War broke out in the summer of 1936. Socialists, radical democrats, and anti-fascists worldwide mobilized to support the Republican cause. Missak immediately engaged in fundraising for the Republicans, joining the Popular Front and Comité d’aide aux Républicains Espagnols, led by André Malraux. He intended to travel to Spain but was held back due to the shortage of skilled organizers in France and his role as editor-in-chief of Zangou.[3]

Missak was fully aware of the dangers of rising fascism in Spain. The memory of the genocide was deeply imprinted in his consciousness, warning of the devastating violence that ultra-nationalism and xenophobia could inflict.[4] This violence was often incomprehensible to the French and wider Western world, which remained indifferent to the violence their governments inflicted on the peoples of Asia and Africa, far from their metropoles.[5]

One writer suggests that this warning served as a motivating factor for the small, yet notable, participation of Armenians in the International Brigades: “These Armenians, who became stateless due to the xenophobia and genocidal policies of the Ottoman Empire, simply could not tolerate the outbreak of fascism in another part of the world and joined the struggle against fascism, sometimes at the cost of their lives.”[6]

The threat of fascism arrived on the doorstep of France when the Nazis invaded Poland in September of 1939. Following their declaration of war, the French government “initiated a fierce crackdown against hundreds of foreigners in France, most of whom were stateless communists or left-wing dissidents who, as a result of the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact of August 23, had been transformed overnight into enemies of the state.”[7] Missak was swept up in this wave of repression but was eventually released after lobbying to join military service. In a letter to Melinee, he described that moment as an opportunity to reaffirm their commitment to France.[8] The HOK, rebranded l’Union Populaire Franco-Armenienne, was disbanded by the government.[9]

Following France’s defeat and the establishment of the Nazi occupation and Vichy regime in 1940, Missak was demobilized from his primary role as a fitness instructor and began work in a factory. There, he witnessed the deadly impact of the fascist occupation when he found the body of a Black worker who had been murdered by the collaborationist forces managing the factory.[10]

The Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 led to a second wave of arrests in Paris, targeting foreigners and known dissidents. Due to a combination of insufficient evidence regarding Missak’s crime of being a communist, and the overwhelming number of arrests, he was released in September of that year. Upon his release, Missak immediately joined the Resistance where he quickly rose to a leadership position in the FTP-MOI. He commanded his own detachment, which gained fame for its acts of sabotage and assassination against the Nazis, but Missak was eventually captured and executed in 1944 following an intense hunt led by the collaborationist regime.

A Monopoly on Memory?

Understanding the significance of pantheonization requires a brief examination of the competing narratives surrounding the FTP-MOI. First, let’s look at the history of the Pantheon and its impact on French society. Originally built under the reign of Louis XV in the heart of ancient Paris, the building alternated between a mausoleum and a church until it became the Pantheon we know today, completed just before the French Revolution, following the death of Victor Hugo.

In modern France, the President decides who is honored in the Pantheon, a strategic act used to define one’s term through a potent symbol of French consciousness. This may seem paradoxical considering Manouchian’s communism and Macron’s criticisms of the poor for prioritizing streaming subscriptions over buying organic apples. However, using memory for political expediency has precedent.

In post-war France, rival political forces with divergent, and sometimes overlapping motivations, shaped the mythologization of the Resistance. Stateless dissidents like Missak, anti-fascist Italians, and Jewish rebels who participated in the FTP-MOI were largely ignored following the war. This was “to create a much-needed vision of national unity,” with Charles De Gaulle making the Resistance movement “a purely ‘French’ phenomenon”. Accordingly, de Gaulle’s decision to honor famed Resistance member Jean Moulin in the Pantheon in 1964 further asserted the Resistance as unequivocally French.

The state was not the only participant in this affair. The spectacle of the ceremony served as excellent cover for the French Communist Party (PCF), the participation of which was also implied in this selective remembrance process. After the war, the PCF, enjoying significant prestige, joined a coalition government with De Gaulle. It also participated in the “Frenchification” of the Resistance by largely ignoring the role of the FTP-MOI. This marginalization remained mostly unnoticed until the public release of the 1983 documentary film, “Terrorists in Retirement”.

The film’s release, which coincided with the 40th anniversary of France’s Liberation, sparked outrage, particularly from the PCF. The film primarily features former FTP-MOI combatants, but relatives, experts, and Melinee Manouchian herself also appear. The film provocatively “advances the strong suggestion that the clandestine central command of the Party knew of the impending danger [facing the Manouchian Group], but nevertheless refused to take the targets out of harm’s way.”[11] Although an outright betrayal by the Communist leadership is likely false, a historian and journalist validate the claim of erasure of foreign participation.

Nonetheless, the activities of the PCF during the early years of the Cold War tarnished the Party’s reputation among many on the French left. In 1956, the Party voted in favor of the government’s use of “special powers” to suppress the national liberation movement in Algeria. The same year, a short-lived revolution-from-below in Hungary challenged the one-party state’s monopoly over socialism. The Soviet central government’s response was swift and brutal, becoming infamous for images of tanks rolling through the streets of Budapest to repress workers and activists. The party’s high-ranking officials’ lack of self-criticism for their complicity in propagating French chauvinism and Stalinism were the subject of a scathing criticism in the resignation letter of leading intellectual and pantheonized figure, Aimé Césaire.

Liberté, Égalité, Nationalité

We can’t know what Missak might have said or done in response to the PCF’s indifference towards the Algerians’ war for independence or the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. It is surprising that there is no mention of the colonial situation in Missak and Mélinée’s writings (that we know of), especially considering Paris’ reputation as an anti-imperialist hub among North and West Africans, Chinese, Vietnamese, and others during the 1930s. This gap could be due to Missak’s commitment to preserving the Republic from the existential threat of fascism. We know that Missak remained devoted to France, even after his nationalization applications were denied twice. This gap, however, is significant and deserves further study.

The concept of pantheonization has sparked a wave of romanticism, which aims to gloss over the complexities surrounding foreign participation and the ensuing quest for recognition. Some see the Manouchians as embodying the supposed universalism inherent to Republican ideals. However, a closer look reveals this extension of ideals is uneven, influenced by varying definitions of what constitutes a human. President Macron claims that Missak would be granted asylum today, yet he simultaneously defends France’s recent immigration-targeting legislation. Macron endeavors to present the members of the FTP-MOI –– communists, anti-fascists, and committed socialists –– as children of France. However, they would likely recoil in horror at his abolition of the wealth tax and vicious treatment of protestors by the police. These contradictions beg the question: Does entrusting memorialization to the state or party risk forcing Missak Manouchian into an ill-fitting mold?

Footnotes:

[1]Manouchian, Melinee. Manouchian. p 61-63. A thank you is due to Taline Oundjian, first for giving me a copy of the aforementioned book, and second for her patience in the translation of the select quotes which appear in this text. Any mistakes are my own.

[2] Title of a poem written by Missak in 1924-25, “Դեպի Ֆրանսա”. Մանուշյան, Մ․ Բանաստեղծութիւններ․ 1946.

[3] Manouchian, Melinee. Manouchian. 1974. p. 57.

[4] Ibid. p 58.

[5] “People are surprised, they become indignant. They say: “How strange! But never mind-it’s Nazism, it will pass!” And they wait, and they hope; and they hide the truth from themselves, that it is barbarism, the supreme barbarism, the crowning barbarism that sums up all the daily barbarisms; that it is Nazism, yes, but that before they were its victims, they were its accomplices; that they tolerated that Nazism before it was inflicted on them, that they absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples; that they have cultivated that Nazism, that they are responsible for it, and that before engulfing the whole edifice of Western, Christian civilization in its reddened waters, it oozes, seeps, and trickles from every crack.” Cesaire, Aime. Discourse on Colonialism. p. 36. https://files.libcom.org/files/zz_aime_cesaire_robin_d.g._kelley_discourse_on_colbook4me.org_.pdf

[6] Bakhchinyan, Artsvi. The Spanish Civil War and the Armenians. p 128.

[7] Caron, Vicki. The Missed Opportunity: French Refugee Policy in Wartime, 1939-1940. p 123.

[8] “This challenge will be the occasion for each of us to precise our behavior towards France… Every citizen must have the heart to fight Nazism, enemy of all people.” Manouchian, Melinee. Manouchian. p. 64.

[9] Ibid. p 66.

[10] Ibid. p 74-75.

[11] Young, Patrick. Review of “Des Terroristes à la retraite”, 1983. H-France Review Vol. 1 (March 2001), No. 5.

Also see

Towards a Franco-Armenian Strategic Partnership?

The Coordinating Council of Armenian Associations in France recently hosted its annual dinner in Paris against the backdrop of heightened geopolitical tensions and concerns over Armenia's security. The focus shifted to the role of France in implementing deterrence measures and sanctions against Azerbaijan.

Read moreFrom the Forgotten Pages of History: The Resistance of Louise Aslanian

From Tabriz to Paris, from resistance to a Nazi concentration camp...this is the story of Louise Aslanian, an Armenian woman whose convictions, commitment and words have largely been forgotten.

Read moreRecently Published

Reporting for the International Press While Armenian, Part II

In the second installment of a series, Taline Oundjian examines the process of media information dissemination, offering insights into practical and theoretical aspects. This understanding sheds light on the challenges media encounters and its implications for coverage, especially in countries like Armenia.

Read moreAliyev Uses Religion to Hide His Dictatorship

Allegations against European institutions of being Islamophobic, a serious assertion by Azerbaijan, is part of a much larger anti-West campaign which is often insufficiently understood and analyzed by Western partners, writes Tatev Hayrapetyan.

Read moreFreedom House Assesses Armenia’s Democracy

Freedom House's Nations in Transit 2024 report downgraded Armenia's democracy score. It also highlighted the spread of autocracy in the region, emphasizing that Western democracies have been inconsistent and hesitant in defending international norms, enabling autocracies to evade accountability.

Read moreEmbracing a Culture of Kindness

While Armenians pride themselves for their hospitality towards foreigners, sometimes the same gesture isn’t extended to their fellow Armenians, particularly to those in need. If we could learn to embrace kindness and share this generosity, we could greatly enhance the well-being of all Armenians, writes Ella Kanegarian-Berberian.

Read moreEVN Report

Media Festival 2024

See the guest lineup here