August 1893, Vienna

While visiting Vienna, Austria with her mother and sister, Mariam Tumanyan was invited to a dinner with the Armenian elite in honor of Khrimyan Hayrik. However, the women were not allowed to be at the same table as him, hence were seated in the next room where they could hear the conversation. After Khrimyan Hayrik left the dinner party to go to his hotel room, the women were invited to join the other men, including several priests.

Inspired by the evening, Mariam managed to overcome her shyness, picked up a glass of wine and began to speak:

“It’s a common thing to say thank you when someone praises you, but today, I want to break that habit and reprove those who praised us. Yes, today you are surprised and pleased that an Armenian woman is sharing a table with you, but do you not remember the brave women from our history? Women, who were as strong as men, women who were men’s comrades-in-arms. If today, women have restricted themselves to their families and are not active in social life, who is to blame? Of course you, the men. If you try to ensure higher education for your sisters and daughters, and seek a friend in marriage, the Armenian woman would not be that despondent and would bravely compete with you in the public sphere. …As I listened to your speeches, I’m sure that you all are keen to see the development of the Armenian woman, therefore I drink first for our dear Hayrik (Khrimyan Hayrik) and then for you all.”

Image: Young Mariam. Backdrop, Shushi.

“There were several hundred girls from different classes, with different educational levels. Only a few of them were concerned about their education, and I had the impression that most of them were there just for formality and wanted to be rid of it as soon as possible. They used to cheat on assignments…They were pretending to be sick…”

Childhood and Education

Countess Mariam Tumanyan was born in 1870 in Shushi, in a family where education was highly valued. Her father, Markos Dolukhanyan was an intellectual, a judge and a famous public figure. Mariam’s mother, also born into an aristocratic family, was raised in Tbilisi and attended the Gayanyan School for Girls.

Living in 19th century Tbilisi, the cultural and educational center of Armenia at that time, the Dolukhanyans spared no effort to educate their children. In 1877, Mariam entered the Gayanyan School in Tbilisi at the age of seven, where she studied European languages, arts, dance, the piano and embroidery․

“From a very young age, we [she and her siblings] were required to speak German and French each day. Thanks to this, by the age of 16, I could read literature in the original language.”

Mariam remembers being a very hard-working child. After five years of studies at Gayanyan, she left to attend the Tbilisi Gymnasium for Girls, where the behaviour of her peers completely changed her perception of education and set her apart from society. Mariam believed that education was the key to success and the only way to change a woman’s role in her reality. She was terrified by the careless approach of her peers and could not accept their behavior.

Marriage and Social Life

While enjoying a holiday in a countryside house, Mariam was introduced to the young Count Georgi Tumanov, who visited her with the intention to marry.

Soon, 16-year old Mariam, fully devoted to her education, married Count Tumanov, a successful and famous publicist and editor. Mariam, an ardent patriot, an admirer of Armenian language and literature entered a family of Georgian-Armenians, where nobody spoke Armenian.

Most Armenians living in 19th century Tbilisi, preferred the culture and lifestyle of Western countries. Mariam was incensed that people were bullied for trying to maintain the Armenian language and found herself in a family where Armenian culture and traditions were considered out-of-fashion.

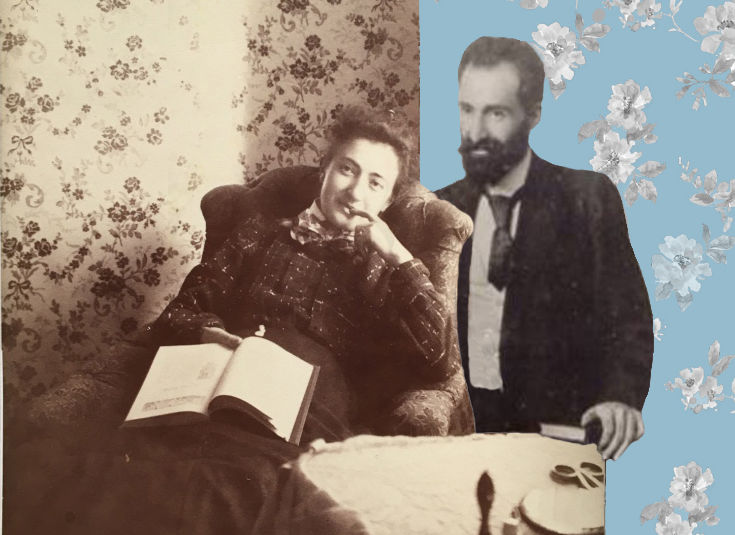

Image: Mariam and Georgi Tumanov as newlyweds.

“The main goal of a lady is to get married, Mariam. You are already engaged, there is no need to continue your education,” the Countess would hear all the time.

“When my oldest son was born, I started to speak Armenian with him. Oh God, how my mother-in-law taunted me! She would do a parody of me, thinking that she wasn’t offending me, but I was feeling indignant. I decided to place an announcement in a newspaper asking for an Armenian-speaking nanny. I got many responses, but when they were told that they would have to stay overnight at our house, they immediately refused, saying that their parents would never agree. ‘How can I do that, it will tarnish my name,’ they would say.”

Mariam was one of the few people who saw this trend as a serious threat and later in her life, she spoke about her struggles to change the perception of Armenian culture in her society.

Literary Thursdays

In 1891, the Countess officially launched her public activities. Publisher and public figure Tigran Nazaryan, suggested that she organize a ball for his publishing agency. Mariam refused at first. “I did not want to embarass myself,” she wrote in her memoirs later. Yet her inner desire to help people and be an active community member finally persuaded her to agree. At first, she organized various committee balls but not long after she transformed her house into a meeting place for Armenian intellectuals of the time. The Countess would invite notable guests such as Hovhannes Tumanyan, Levon Shant, Dr. Zargaryan, Derenik Demirchyan, Avetik Isahakyan, Ghazaros Aghayan, Shirvanzade and others.

Every Thursday they would discuss literature, all things Armenian and interestingly each other’s literary works. They called these meetings “Literary Thursdays.”

Mariam Tumanyan was very devoted to the cultural life of the Armenians in Tbilisi. She would spare no effort to organize everything perfectly and would go from city to city to fundraise for Armenian writers.

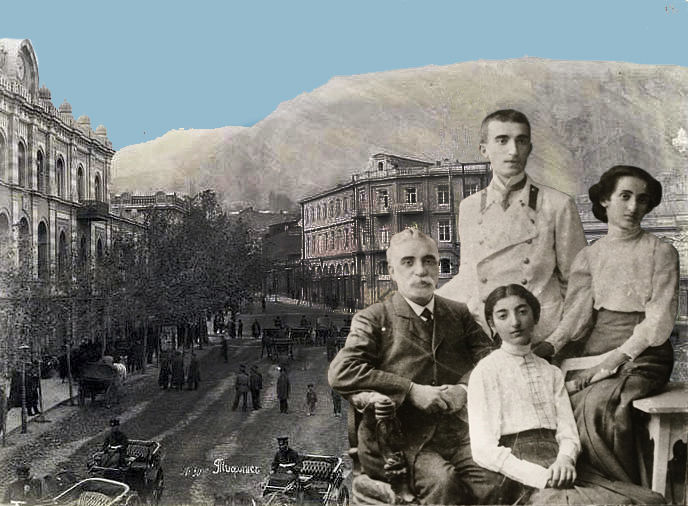

Image: Mariam Tumanyan’s husband and children. Backdrop Tbilisi.

“Because it was considered ‘out of fashion,’ our children were being raised by foreign nannies and were being torn from their national spirit.”

“I had already organized Chinese and Indian-themed balls, tea evenings…in 1889, I decided to include Armenian traditional dances. When I relayed my idea to the board members of our publishing company, they were shocked. They tried to persuade me that Armenian music and dances would disgrace the company’s name. At that time, people used to think that national songs and dances were only for illiterate people.”

But she was persistent. With the help of Christopher Kara-Murza, a famous Armenian composer and conductor, the Countess started preparations for a special national evening. They gathered young dancers and started to teach them Armenian dances for weeks.

“At first, the young dancers were not serious. They would laugh and make fun of our national songs…But soon, Kara-Murza’s excitement and persistence won over and everybody started to adore our rehearsals…When we finally decided who would dance in the ball, I started to search for Armenian national costumes.”

Despite the concerns of the board members, the evening was a resounding success. Mariam recalled how many of the Westernized society women were moved to tears. “They began to understand the beauty of our national dances and songs,” she wrote in her memoirs.

Countess Toumanyan at the carpet weaving and shoemaking workshops she had set up for the survivors of the Hamidian massacres.

The Countess of the People

In 1895, when Sultan Abdul Hamid II organized widespread massacres of the Armenian people in the Ottoman Empire, thousands of survivors fled to Tbilisi and other parts of Eastern Armenia. The Countess spared no effort to help those in need. Her approach was unique – she believed it was better to provide people with a job and help them get back on their feet.

Armed with this philosophy, Mariam opened a carpet factory in 1895 for the refugees and later an orphanage in Dilijan. She moved to Dilijan for several months and taught the orphans music and embroidery. One of the orphans remembered how the Countess used to bathe them and give them as much love as she could. And this was just the beginning.

Later, during WW1, Mariam continued her activities. She opened several factories for unemployed emigrants and managed to open a hospital in Abastumani for people suffering from tuberculosis. She would never differentiate people by their nationalities. When once there was a big fire at Chkhsr village in Georgia, the Countess organized a charity evening to support the Jews living there. Her kindness had no borders.

Living in a wealthy family, interacting with aristocrats and even with the queen of the Russian Empire Maria Feodorovna never made Mariam selfish or arrogant. She strongly believed that the most important character of a woman was her intelligence and not her clothing. She used to dress simply because she thought that her “look of luxury could offend the poor.”

Mariam Tumanyan: The Publisher and Children’s Magazine Columnist

In the beginning of 1900, Mariam Tumanyan started to actively participate in publishing activities of the Armenian community. Katarine Lisitian, the editor of the children’s magazine “Hask” suggested she write a column for the magazine and she immediately agreed to create a special section for Armenian children.

Mariam’s column was called “From the Bag of Grandma Mariam” and involved logical games, interesting stories and advice for children. Mariam continued writing her column until 1910, when she traveled to Europe for medical reasons.

“When I was a child, my family used to receive a French children’s magazine, which was called Saint Nicholas. We were so excited about it and would impatiently wait for the new issues. There was a special page, where children could publish their own writings and it’s hard to explain our excitement when we would see our names there. So I decided to have a column like that and introduce myself as an old lady who is teaching games, giving advice and asking questions to the children. It was successful from the very first issue. Little children were writing me letters, asking questions. This column was a new thing in our press and even a Russian magazine asked to copy it.”

“It was a warm and fine day…there was a soft wind from the mountains which was bringing the smell of flowers. Suddenly, it became dark and the stars began to shine. It was calm on the street and I felt that everything was leading to an intimate conversation. But our conversation was somehow incoherent that evening. Tumanyan would become silent occasionally, and was looking at me differently. I don’t know why I became confused and my heart started to beat faster. He said, ‘I want to confess something to you Marmar (this is what he called me during our intimate conversations), I’m in love with a woman, but she doesn’t know. If you can imagine how I struggle, how many sleepless nights I’ve had, but now my heart is calmer and I can speak about that easily.’”

The Countess understood that ‘the woman’ Tumanyan was talking about was her. After much turmoil and many sleepless nights, she understood that “he was the same person to me, he was my lovely poet and my sweet friend.”

Writer Hovhannes Tumanyan and Mariam Tumanyan met in 1892, in a publishing house, where they were both working. He was an amateur writer, she was a new board member. The Countess wrote that when they met, the poet immediately captured her attention.

“He had a very fine face, and was smiling all the time. His sparkling eyes were reflecting his poetic spirit and I could see in those eyes so many emotions and an excitement that would never let me ignore his personality.”

Mariam and Hovhannes would write letters to each other often. When they were together, they would spend hours discussing culture and Armenia. They would call each other soulmates.

Mariam was so obsessed with Tumanyan and his poetry that her husband would sometimes call him “Your Pushkin.” Soon, Tumanyan became a good friend of the Tumanovs and was under the patronage of the Countess. The writer was struggling as a novice writer and faced crippling financial problems. Over the years, Mariam was supporting him not only financially but also also psychologically, she wouldn’t let him give up. In her memoirs, the Countess describes Tumanyan with all his flaws and insecurities. She remembers how many times she was angry at him for his irresponsibility in financial matters. Yet this was not just a simple friendship.

One evening in 1908, Tumanyan confessed his love…

The Countess never wrote in her memoirs whether she loved the great Armenian poet or not. However, after Tumanyan’s confession, their relationship changed. Tumanyan started to ignore her and years later, refused to take her with his family while escaping from Stalin’s repressions.

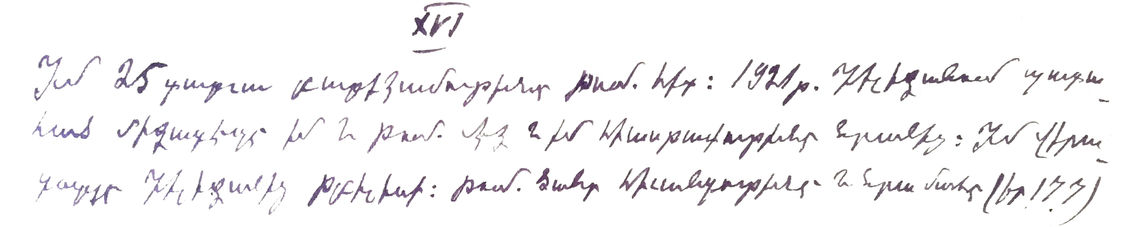

Excerpt from Mariam Tumanyan’s diary: “My 25 year friendship with Tumanyan. The incident that happened between us in Dilijan in 1921 and my disappointment in him. My return to Tbilisi. Tumanyan’s heavy illness and his death.

Dilijan, the Orphanage

The Tumanovs had a beautiful country house in Dilijan, and the Countess used to go there every summer with her children. In 1915, however, Dilijan was full of refugees from Western Armenia who had fled the massacres organized by the Ottoman Empire. There were thousands of orphans who were suffering from hunger and various diseases. In her memoirs, Countess Mariam Tumanyan describes the horrifying faces and conditions of the refugees, she recalls the sad eyes “reflecting their horror.” Mariam soon became the head of one of the orphanages and started to take care of dozens of orphans.

“I could not describe the condition of the orphanages… Almost all the children were struggling from diarrhea and all the floors of the rooms were full of feces. Children were moving through the rooms like shadows… Most of them were very exhausted and could barely stand on their feet, so we had to keep them lying on their beds… One day I noticed that there was a red protrusion from the buttock of a child. I could not understand what it was so I called a doctor. But he did not come, saying that he had patients who were in critical condition. The child was suffering immensely and I decided to visit the doctor and get his advice. He said that it was the child’s bowel and it was because of the diarrhea. And he explained how to cure the child. I was afraid to do it but there was no other choice – the child was struggling… She was crying and that was making me more nervous…but after several days, her condition became better and she slowly began to recuperate. So I was more confident later on and in these kinds of situations I was not even calling the doctor. “

When September came, the Countess did not leave Dilijan. She sent her children to Tbilisi to attend school and she stayed with her orphans.

After the formation of the Soviet Union, Mariam Tumanyan was deprived of her title of countess and while her family faced huge financial issues, she never stopped her social activities. She continued to help people and was actively engaged in the cultural and educational life of the Armenian people. During the Stalin repressions, Mariam Tumanyan’s two sons and brother were arrested and exiled. They never came back.

Toward the end of her life, Mariam dreamed of moving to Yerevan. It was a dream that she was never able to realize. Mariam Tumanyan died in 1945, at the age of 75 in Tbilisi.

“In October, there was snow in Dilijan. The poor orphans did not have proper warm clothes and I had to go to Tbilisi. After I was done with my shopping and it was time to leave for Dilijan, I became sick and had to stay at home. My father was trying to persuade me to stay in Tbilisi but I was resisting. He argued that I had to think of my own children first. He even threatened me and said that if I go back to Dilijan, he will never recognize me as his daughter again. My poor father, you have forgotten that I was a mother of six children….You were right, I had to think of my children, but here are thousands of struggling and emaciated children, deprived of maternal love… how could I leave them…”

-

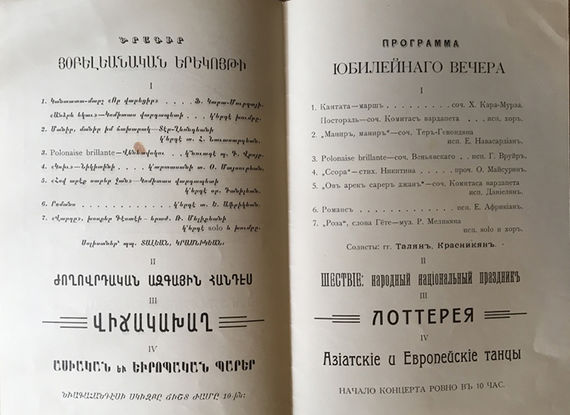

An invitation to a charity event organized by Countess Marian Tumanian.

-

The opening of the Caucasus Armenian Benevolent Society hospital in Georgia. Mariam Tumanyan is seated in the middle.

-

Dining room of The Caucasus Armenian Benevolent Society orphanage in Georgia established through the efforts of Mariam Tumanyan.

-

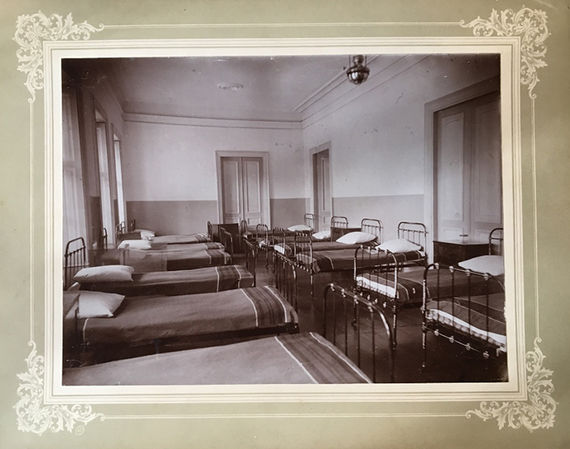

Bedroom of The Caucasus Armenian Benevolent Society orphanage in Georgia.

-

The Armenian orphanage in Dilijan.