Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The “Outside In” series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Outside In

Essay 3

Here it is, the Zone, just around the corner… a terrain like any other terrain. The sun shines over it, like over the rest of the earth, and nothing seems to have changed, everything seems to be like it was 13 years ago. Deceased dad would have looked and would not have noticed anything special, except that he would have asked: Why is there no smoke over the factory? Is there a strike?.. Yellow rock cones, blast furnace air heaters shine in the sun, rails, rails, rails, a train with platforms on the rails… Only there are no people. Neither alive nor dead.

Excerpt from the “Roadside Picnic” by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky.

Translated by the author

The “Fairytale” Is Over

The Soviet project was marked by its ambitious and ambiguous social and political experiments, endeavoring, at least de jure, to create a utopian society that believed deeply in the collective over the individual. In this respect, social infrastructure designed for children ranging from daycare and schools to summer camps and various extra-curricular activities were sites for shaping the young Soviet subject. Here, children were imbued with ideals of communism, camaraderie and Soviet rationality.

Children’s summer camps were microcosms of youthful exuberance. Imagine a place where the mornings were greeted with the enthusiastic chatter of children and the evenings whispered to sleep with songs of unity around the campfire. The air resonated with the clatter of activity and the spirit of shared experiences. It was a place where friendships were forged over shared meals, stories and dreams. Yet, the summer camp was not merely about leisure. It was about instilling a sense of belonging to something larger than oneself, where each and every one was a part of the grand Soviet narrative. But as history’s wheel turned, the Soviet Union collapsed, leaving behind various places that once brimmed with life and ideology.

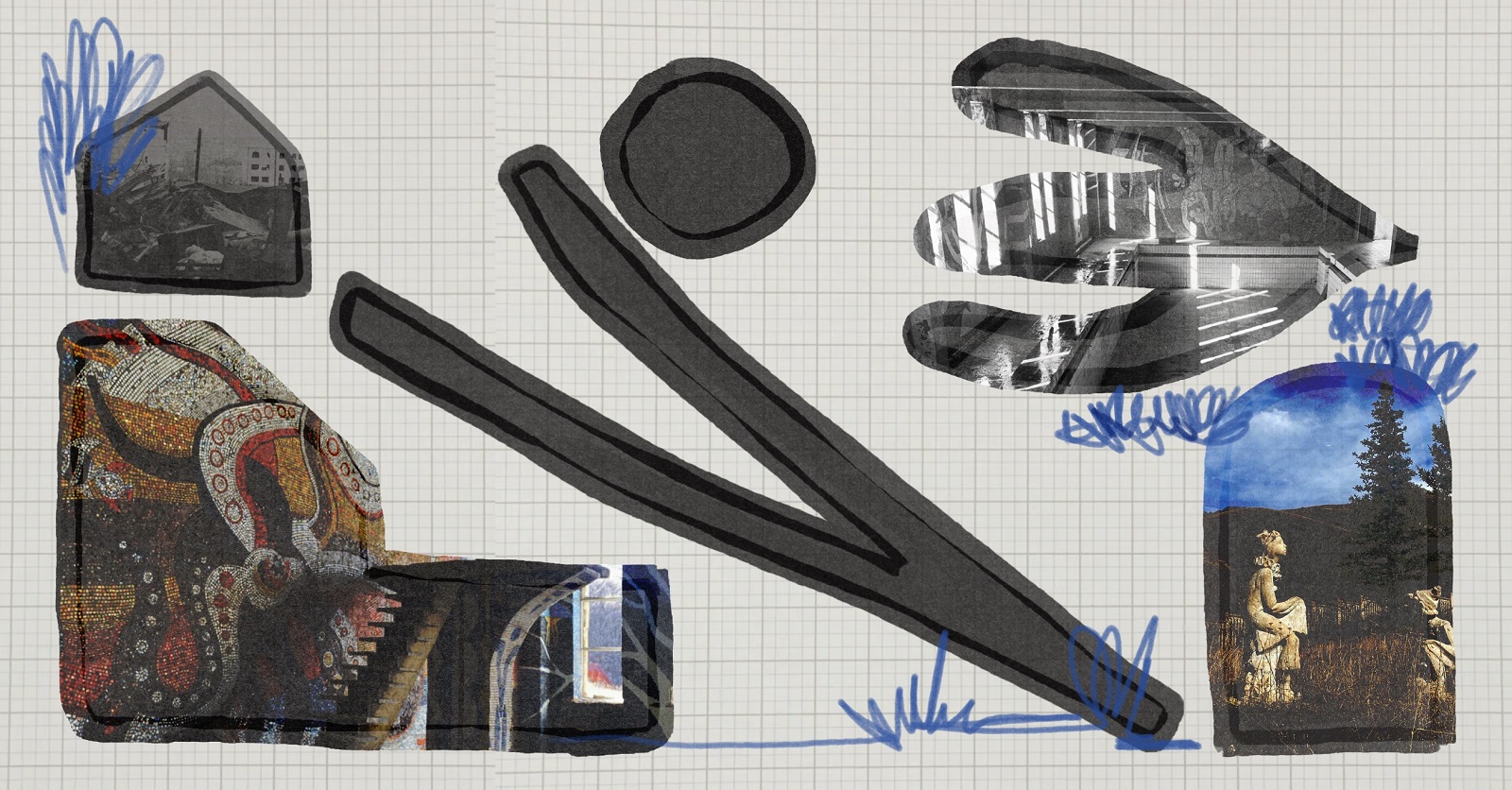

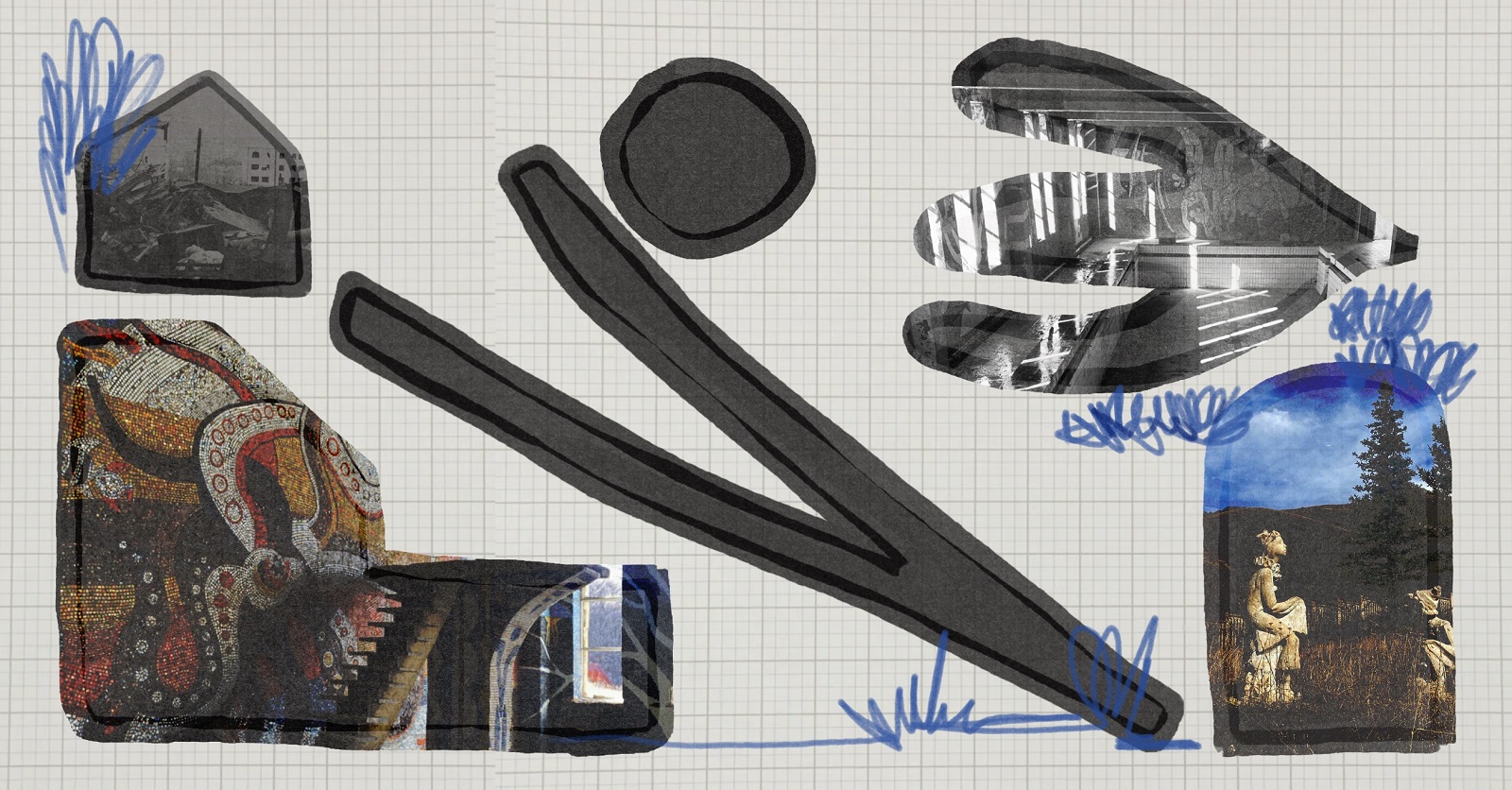

One of these Soviet summer camps, now completely abandoned, lies at the foot of a mountain near the city of Spitak in the Lori region of Armenia. After the Spitak earthquake of 1988, the camp hosted its victims and then ceased all operations around 1993. I came to visit it in mid-spring 2023, when the snow had just melted, and the first greens began to make their way to the surface between last year’s yellowish grass. The first thing I saw, when approaching the grounds, was a rusty plate with a partly faded word Skazka [сказка, fairytale in Russian] engraved on it. Further down the road on the right side was a building with a wall lavishly decorated with large colorful tiles depicting a young man and two women running alongside a horse, suggesting the harmony between humans and nature.

Entry into the grounds of the camp was easy, there were no fences, gates, or guards. Among the numerous vacant buildings stripped of all valuable assets, such as the canteen, administration units and dormitories, the indoor swimming pool is the one that fascinated me most. The walls of the pool were covered by marvelously intact sea-themed mosaics in natural, subtle colors. The mosaic obviously served not only as a decorative element but also as a powerful tool for ideological messaging and visual storytelling. White figures of young, athletic females and males surrounded by the blue water and a variety of sea life. Flocks of fish scurrying among the coral, an octopus extending its tentacles. Divers hold sea creatures in their hands, manifesting the conquest of nature by humans — a vivid reminder of Soviet goals and aspirations. Captivated by this masterpiece, at the same time, I felt uneasy. There is something both attractive and repelling in places of present absences, of bygone grandiosity. When only your own movements distort the surreal stillness and the echo breaks the silence, solitude and humility become embodied conditions.

Walking out of the pool, I strolled on overgrown paths, occasionally finding myself among bushes and knee-high grass. Then pale concrete sculptures of two characters from a Soviet children’s book “Golden Key or The Adventures of Buratino” caught my eye. Here, Buratino still looked into the distance with a hopeful smile. But sitting opposite him, melancholic Piero, covered with bits of orange lichen, seems to have understood — the communist fairytale that aspired to bring happiness to all yet ended up in immersed losses — is finally over. It collapsed under the weight of unsolvable contradictions, exacerbated by technogenic catastrophes, natural disasters and ethnic conflicts of the 1980s. From Buratino, my thoughts turned to yet another literary piece that largely formulated contemporary popular imaginaries of abandoned areas.

Appeal of Post-Soviet Abandonment

In 1972, writers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky published “Roadside Picnic” which became their most popular and widely translated novel outside the former Soviet Union. The central character of the novel is the Zone – a desolate area of alienation where an extraterrestrial visit occurred and which subsequently became a place of an incomprehensible anomaly filled with obscure, predominantly deadly substances and objects. For the Strugatskys, the Zone is an area of an experiment that very accurately interprets the Soviet reality — a cluttered space, where traces of “great victories”, utopian ideas, unfulfilled grandiose plans, fatal errors and testimonies to both altruistic and vicious sides of human nature lie mixed up. This philosophical science fiction novel is somewhat of a prediction about the future of the Soviet project. Upon its dissolution, it created vast areas of abandonment and no-go zones that froze in time. However, they continue to supply post-Soviet societies with ideas that cement the nation-states formed on imperial ruins.

Just like the Zone, post-Soviet areas of abandonment — factories, sanatoriums, camps, and even whole settlements — are marked by shadowy and mysterious attractions. They are filled with objects and structures whose purpose we do not fully understand. Their unique aesthetic is linked to the starkly visible undoing of mighty Soviet modernity, which, in the words of anthropologist Alexey Yurchak, was “forever until no more.” Providing us with a glimpse of our planet’s inevitable post-human future, these places remind us of how fragile the world that we inhabit is and how easily and unexpectedly it might be destroyed by war, pandemics, global climate change, food shortages, economic crises, etc. In a fit of pride, we often forget that Homo Sapiens is just one species existing for less than a quarter of a million years, that is, less than a tenth of the life span of biological species. There will come a time when human civilization as a whole will turn to dust, barely leaving a trace on the surface of the sand of geological time. Every elegant ruin or formless decomposing rubble we encounter is a timeless truth — that in the grand tapestry of time, we are but passing shadows, and it is in embracing this transience that we find a deeper understanding of life and our place in it. Until the material relics of the Soviet Union disappear for good, we are deemed to revisit them, provoking thoughts about what societies value, how they evolve, and what they leave behind.

You Are Not Alone

It is a common perception that vacant buildings and abandoned areas attract vandals, homeless people, drug users, and destructive teenagers. Despite the obvious absence of people, I could nevertheless see (semi)fresh marks of human activity around me when I visited the summer camp. Traces of fires, piles of garbage, broken objects of all kinds and graffiti. It even seemed that there were corners in vacant buildings where someone had deliberately assembled various forms of debris. I am convinced that recurring visits and observations of the camp would show various human-made changes — movements of things, new inscriptions, new breakdowns. This is what anthropologist Martin Demant Frederiksen called “trash-speak”, when he was doing his research in an abandoned hotel in Croatia and engaged in conversation with elusive interlocutors through the rearrangement of objects, graffiti and notes. In this sense, abandoned places remain arenas for engaging not only with history but also with the present, arenas for mediated human communication. However, it takes a special mood or even mindset to understand and decode hidden meanings in such improbable places of loss and spontaneity. There is also one pragmatic piece of advice. When embarking on a journey to an abandoned place, for the sake of your well-being, do not forget to wear comfortable, thick-soled but lightweight shoes. Just in case there is a need to run.

Outside In

Essay 1

A Place on the Edge of Armenia’s Urban Geography

Once an agricultural settlement, tidily inscribed into the picturesque mountain landscape, Dastakert was remade by the Soviet state into a site of copper-molybdenum extractivism. That project failed. What happened to the city?

Read moreOutside In

Essay 2

The (Un)Fairytale of Siranush

Following the story of Dastakert, Armenia’s smallest city, this next essay in the “Outside In” series looks behind the veil of yet another small Armenian city and offers a glimpse into the lives of its “void dwellers”, namely Siranush.

Read more