Listen to the article

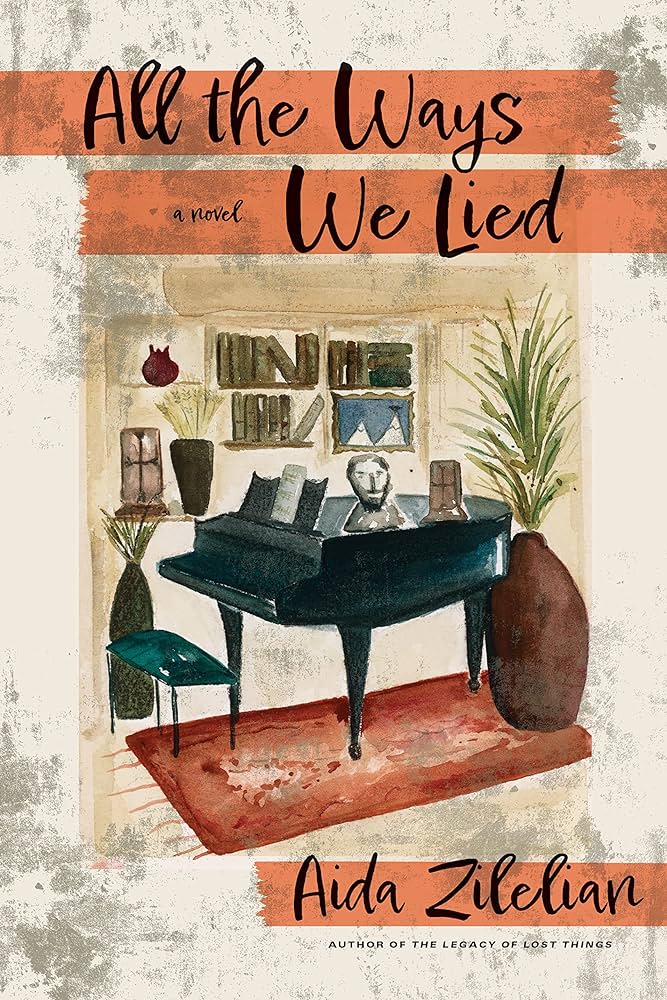

ALL THE WAYS WE LIED

by Aida Zilelian

Turner/Keylight

Release date: January 2024

If you thought that Chekhov’s three Prozorova sisters led complicated lives, then wait until you meet the Manoukians of Jackson Heights, Queens. School teacher and eldest sister Kohar, the novel’s erstwhile protagonist and hero, has for years unsuccessfully been trying to have a baby. She also despairs at her perennial role as foiled peacemaker in a family of traumatized women. Her middle sister Lucine toils away day and night as an underpaid pastry chef while her nogoodnik husband gambles away her life savings. As for her little half-sister Azad, she inherits money and leads the prototypical life of a spoiled child, attending Burning Man gatherings in the Nevada desert and moving from one failed relationship to another. When she finally meets a guy she really likes, the Gods have other plans in store for her. And lording her misery over all three girls is their formidable mother Takouhi. The daughter of Armenian Genocide survivors from Lebanon, she herself has survived both a first marriage and the sterile confines of overly restrictive Armenian traditions. Meanwhile, her beloved but cowed second husband Gabriel showers his love on the daughters, editing books while smoking and eating his way to ill health.

Zilelian’s All the Ways We Lied turns the family saga squarely on its head: gone are the bland descriptions of family squabbles or the commonplace platitudes that populate much of the genre. Instead, the author places her characters naked in front of the reader, their virtues and sins to be adjudicated in the court of contemporary literature. The novel’s locale, a staunchly middle-class immigrant neighborhood, provides a refreshing change from the repetitive dramas we are often serenaded with that take place on the wealthy Upper East Side or in the faux-bohemian realms of downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn. These are real people with real-life problems—and we are eager to meet them. As the sisters take stock of life’s expectations and try to negotiate what is left of the American Dream, Takouhi organizes, cooks and shops after work in her weirdly warped attempt to be a perfect mother and wife. But her depression and manic existence tear apart at the family’s fragile fabric. In one of the novel’s early chapters, the narrator describes her crazed early morning routine: “The alarm bell sounded. Takouhi, awake for hours before dawn, lay with her eyes open as the ringing blared in her skull…the list of daily tasks, items that needed desperately to be completed, had grown steadily…” This isn’t just another manic Monday, but rather a description of Takouhi’s daily 24/7 existence.

In time the reader learns that the Manoukian matriarch, once a child prodigy in Beirut, was forced to give up a promising singing career deemed unsuitable by her poor and uneducated parents. Now Takouhi is bad news all-around, calling her girls at all hours of the day and night, endlessly judgmental and self-centered. After a particularly difficult encounter with Takouhi, Lucine’s deadbeat husband Steve declares about his mother-in-law: “This has nothing to do with if she loves you or not. It actually has nothing to do with you—that’s the fucked-up part. All she cares about is what is of interest to her.” Zilelian then dispatches the following brutal missive: “It amazed Lucine. How someone as ignorant, ill-bred, and uneducated as Steve could offer such depth of insight.”

Zilelian’s novel also belongs to the realm of post-genocidal literature and indirectly comments on the sometimes quasi-necrophiliac culture that Armenian communities in the diaspora have developed. The author however does us the favor of not rehashing the same old stale tropes about the horrific events of 1915 and the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Yet every Armenian character in the novel suffers from some form of transgenerational PTSD that manifests itself in a long laundry list of inherited quirks and anxieties. Theirs is not a Peaceable Kingdom by any means. Halfway through the novel, Azad decides that young Krikor may finally be the guy to settle down with despite their obvious differences in temperament and outlook: he, conservative and unimaginative, she liberal and unruly. When she finally meets his parents at their house for dinner, things go subtly awry. Azad arrives ten minutes late, which the narrator implies is unacceptable in the Armenian context at hand. Krikor’s mother greets her with cool detachment. After a few pleasantries are exchanged, the conversation quickly turns to Azad’s perceived lifestyle and her recent Burning Man experience in Nevada. With Krikor’s grandmother, a genocide survivor, sitting at the head of the table, the mother slices through the air with smug condescension: “When I think of the desert, all that comes to mind is Der Zor,’…referring to the Syrian desert, where the Ottomans had sent Armenians on death marches during the Genocide.” Although Krikor stands his mother down, the relationship quickly fizzles and fades into Azad’s past.

One of the novel’s great strengths lies in Zilelian’s ability to get at the core of each character’s existential reality. Despite her proclivity for hard work, Lucine starts off a crude and unlikable character who too easily gives in to life’s problems and then lashes out in frustration at her loved ones. In contrast, Kohar seems unable to let go of things and tries to hang on to often untenable situations. Yet as the story unfolds, the author peels away their rough exteriors with dexterity, layer by psychological layer: “Even then, Lucine understood that every heart beat to the proclivity of a lifelong desire. For Kohar, it was respect and freedom. For their mother, it was recognition and praise. For Lucine, it was the affection and attention of her father. She understood herself well enough to know why: very simply, she was the middle child. It had happened so swiftly and forcibly; one day she was seven years old, the center of her father’s world, and the next her parents had divorced.”

In the last part of the novel, Zilelian bravely tackles Takouhi’s foibles and presents a three-dimensional character equally hateful and lovable. Throwing off the pollyannish gloves with which mothers are often depicted in literature, Kohar comes to empathize with her own: “Though most of the (Armenian) women certainly had careers, those of Takouhi’s generation still catered to their husbands in most domestic matters…When Gabriel’s friends came to visit, they would gather in the parlor while Takouhi brewed sourj and poured them into demitasse glasses. Through the growing fog from cigarettes and cigarillos, Takouhi would place the tray on the coffee table and return to the kitchen to bring out the usual assortment of appetizers and return again with plates and forks and napkins. As if a humble caterer, unacknowledged, were trying to enter and leave without disturbing the intellectuals in the midst of their important discussion about the state of Armenia, American politics, a new translation that had recently been published. It was downright oppressive. It would be one of those men that Takouhi would have to suffer.”

These are not easy issues to tackle, and Zilelian repeatedly rejects the stock answer or the hokey psychological assessment. Like her characters’ complex psyches, the author understands that life cannot be easily dissected, its demons easily conquered. When beloved Gabriel passes from cancer, each character finds a way to soldier on. Takouhi creates her own unique if perhaps typically narcissistic way out of tragedy. Lucine frees herself from Steve’s dead weight and seems on the way to a point of clarity in her life. Azad remains young of mind but somehow more lovable. But in the end, it is Kohar who offers the Manoukian clan ultimate redemption. And when it arrives, it is in a form most unexpected yet welcomed, by both Kohar and a satisfied reader.

About Aida Zilelian

Book Reviews

on EVN Report

Tattoos and Silent Heroes: Women of the Armenian Genocide

Historian Elyse Semerdjian’s book, Remnants: Embodied Archives of the Armenian Genocide, presents an innovative approach to writing history. She blends disciplines and challenging narratives to reveal the understudied female experience of the Armenian genocide.

Read moreWhen More is Less: Love and Cement in Revolutionary Yerevan

Christopher Atamian reviews “The Structure is Rotten, Comrade,” a new graphic novel by Viken Berberian and Yann Kebbi.

Read moreThe Eternal Magic of Mariam Petrosyan’s Gray House

Translated into several languages, Mariam Petrosyan’s epic novel “The Gray House” has enchanted readers across the world. In this first book review, Lilit Margaryan speaks with the elusive Petrosyan about her life and the life of a novel that took 18 years to write.

Read moreRe-reading Philip Marsden’s “The Crossing Place: A Journey Among the Armenians”

Philip Marsden’s “The Crossing Place: A Journey Among the Armenians” is atmospheric, gripping and revelatory. It delves into the seemingly exclusive club of a nation at the meeting point of cultures, writes Naneh Hovhannisyan.

Read more

This review offers an insightful and engaging exploration of Zilelian’s “All the Ways We Lied.” The vivid character portrayals bring the complexities of the Manoukian family to life, highlighting their struggles and triumphs with authenticity. The way the author delves into deep themes of identity, trauma, and familial relationships adds richness to the narrative, making it a compelling read. It’s refreshing to see a family saga that moves away from clichés and presents real, flawed characters in a relatable context. The review beautifully captures the emotional depth of the story, and I can’t wait to see how each sister’s journey unfolds against the backdrop of their family’s history. Truly a thought-provoking reflection on contemporary literature!