Hidden in plain sight, Sergey Dmytrevich Merkurov’s House-Museum can be easy to miss.

Located directly beside the city of Gyumri’s more popular attraction, the Museum of Urban Life and National Architecture, Merkurov’s house-museum is oftentimes assumed to be just an extension of the museum of Urban Life. Couple the location, with the fact that the gallery details the life and works of a man not well-known to many today, and the Merkurov House Museum is oftentimes glanced over.

However, skipping the Merkurov House-Museum would be a lost opportunity.

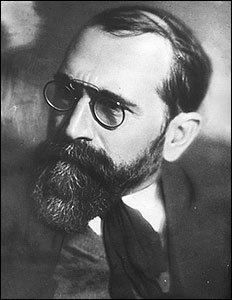

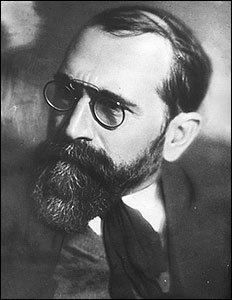

Born in Gyumri in the late 19th century, Merkurov would go on to become one of the most prominent sculptors and monumentalists of the Soviet Union. He was the sculptor of the three largest monuments of Joseph Stalin in the USSR, and his propagandist pieces won him great acclaim, prominence, and influence during his lifetime. His works, particularly his sculpted busts, predetermined the style of the official Soviet tombstone, and over the course of his career, Sergey Merkurov was awarded two Stalin State Prizes (also called the USSR State Prize), two Orders of the Red Banner of Labor, and an Order of Lenin. In addition, he was named the People’s Artist of the USSR in 1943, was Director of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow from 1944 -1949, and became a member of the USSR Academy of Arts in 1947.

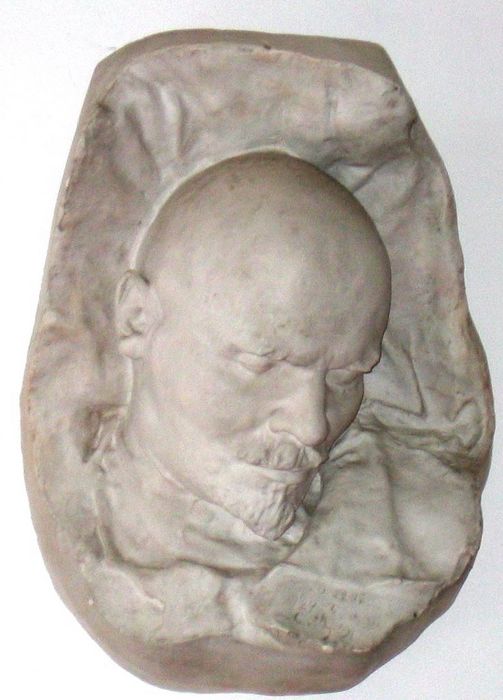

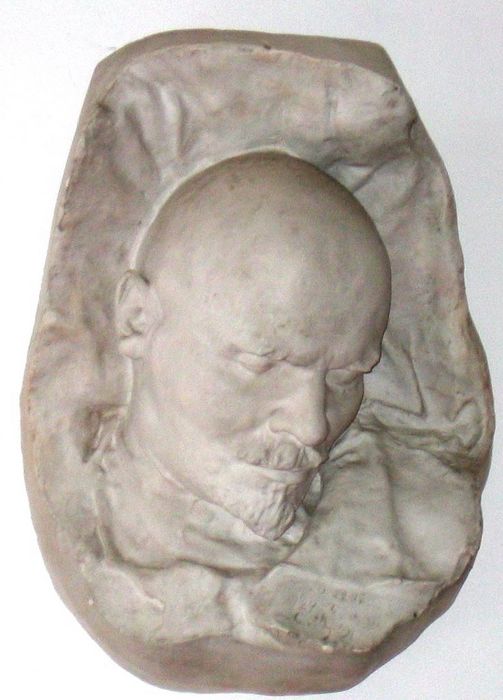

What is perhaps most peculiar about Merkurov, however, and indeed, his claim to fame and the main draw of his museum, is his skill in creating post-mortem masks. Sergey Merkurov is considered the greatest Soviet master of death masks. In fact, he was the favored death mask creator of the time, and was highly sought after to take the death masks of various Soviet luminaries and leaders, as well as prominent cultural figures of the era. On display in the Merkurov House-Museum of Gyumri are 59 of these death masks, including those of Khrimian Hayrik, Leo Tolstoy, Hovhannes Tumanyan, Maxim Gorky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and one of the original death masks of Vladimir Lenin.

By the time of his death in 1952, Merkurov had produced up to 300 death masks and countless renowned sculptures and monuments.

Early Life in Gyumri and Influences on his Art

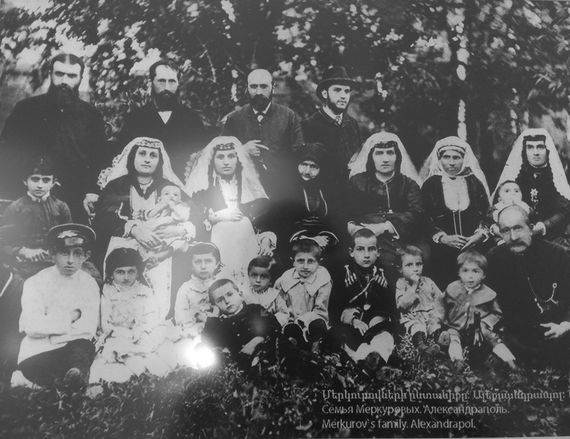

Sergey Merkurov was born in Gyumri (then called Alexandropol) in 1881 to Greek parents. His family had immigrated to Gyumri from Karin (present-day Erzurum) in the 1830s, and settled among the hundreds of other Greek families within the region. Originally Merkuridi before becoming Merkurov, Sergey’s grandfather built the house where Sergey was born (the same house that is currently the house-museum), along with a Greek Orthodox church. Merkurov’s family was undoubtedly Greek… but Merkurov also considered himself Armenian. “My mother and father are Greek, but I am Greek-Armenian,” Merkurov proudly told prominent Armenian poet Avedik Isahakyan. [1]

Indeed, Merkurov’s love for Armenia, particularly Gyumri and its people, is recorded by many of his contemporaries, as well as highlighted by the fact that despite moving from Gyumri at the age of 15, Merkurov never forgot Armenian. In fact, he was known to oftentimes joke around in the Gyumretsi dialect. Mariam Aslamazyan, a fellow Gyumretsi and People’s Artist of the Soviet Union (honored as such in 1990), once even visited Merkurov at his estate in Izmailovo, an administrative okrug of Moscow, writing later in her memoirs that “Sergei Dmitrievich Merkurov… was one of those Greeks who lived in Armenia from generation to generation. He spoke Armenian wonderfully, especially the Gyumri dialect. He cursed very tastefully – also in the Gyumri dialect.” [2]

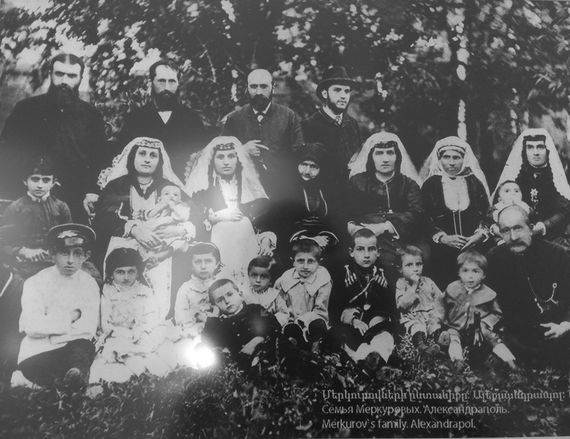

Merkurov left Gyumri in 1896 to attend the Nakhichevan Arts and Crafts college, and then continued on to the Tbilisi real school, from which he graduated in 1901. He entered the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, but was expelled for his participation in political protests regarding workers’ strikes and demonstrations. In 1902, Merkurov entered the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. It was during this period that he attended a political debate and first heard Lenin speak.

It was also during this period that he began to delve deeper and more seriously into sculpture. In addition to philosophy studies, Sergey Merkurov became a pupil of Swiss sculptor Adolf Mayer, who taught him the the important basics of sculpture, form, and material.

At the advice of Mayer, Merkurov left the University of Zurich for the Munich Academy of Arts. There he would study for 14-16 hours a day, attending lectures on topics such as sculpture, drawing, anatomy, and art history. He was particularly inspired by Italian artists like Donatello and Michelangelo, and Merkurov traveled to Italy by foot to see the works of these great masters.

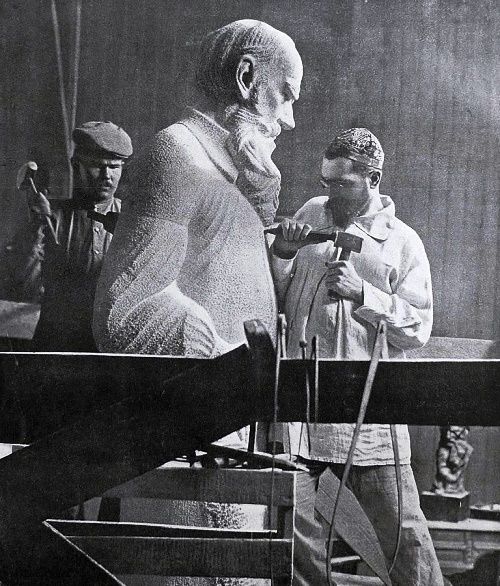

1- Merkurov.

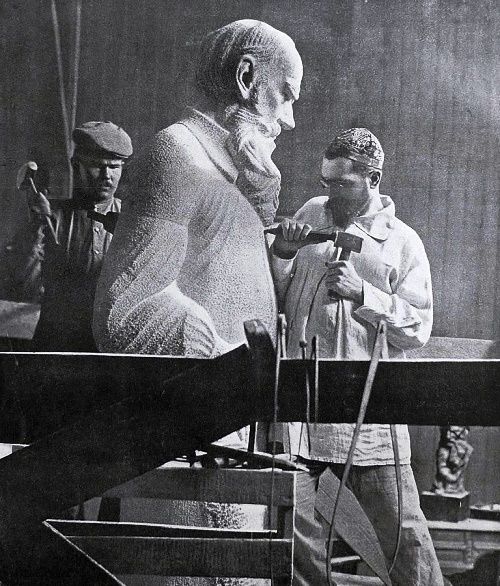

2 – Merkurov in his studio at work on the statue of Leo Tolstoy.

3 – Merkurov’s family in Alexandrapol, 1889.

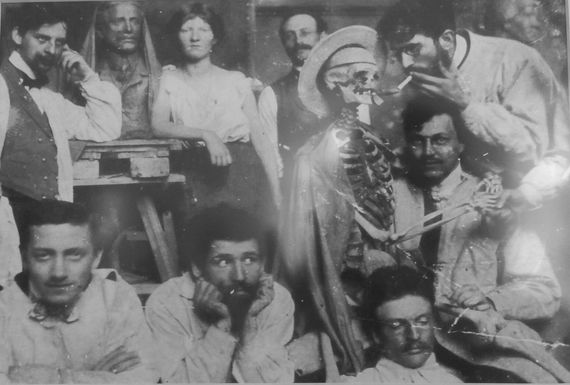

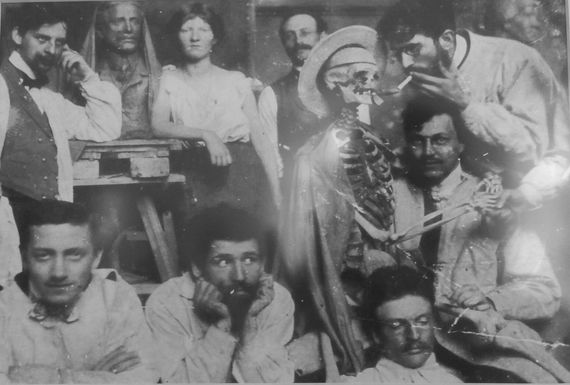

4 – Merkurov at art school.

After finishing university in 1905, Merkurov moved to France, where he lived and worked for the next two years, spending hours in the capital’s museums, particularly the Louvre. While in Paris, Merkurov also became acquainted with the celebrated artist, Auguste Rodin.

The period between 1902-1907 can be described as one of the most influential in Merkurov’s life, in terms of developing his artistic style. In France, Merkurov was influenced by the works of Rodin, the art of symbolism, as well as sculpture and design from the “archaic period” (Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt). As a philosopher of the arts, Sergey Merkurov was also compelled and inspired to employ many of the motifs of thought, contrast, emotion, and death in his work.

Indeed, Merkurov’s style is often described as a kind of “academic modernity,” in which he doesn’t “venture into risky experiments, but retains the characteristic features of this style: the cult of ‘eternal themes,’ especially the theme of death, and the dramatic contrast of the figure and the material (the stone block).”

This style would serve as the key to opening doors for Sergey Merkurov during the Soviet period.

Merkurov the Sculptor: In Yerevan, Moscow, and Beyond

“The Great October Socialist Revolution [of 1917] defined my place in the ranks of the builders of the new society. But not only that – it widely opened the door of my studio,” Sergey Merkurov wrote in his memoir. And it was true. Merkurov and his compositions rose to acclaim after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Works created by him in the past were put on the streets and squares of Moscow (and soon, beyond), and Merkurov began to receive commissions not too long after the April 14, 1918 Soviet decree “On the monuments of the Republic.” This announcement introduced Lenin’s plan of “Monumental Propaganda,” in which the Soviet leader envisioned spreading revolutionary and communist ideology by means of monumental art. As one who believed in the developing ideology of the time period, Merkurov’s interest was piqued.

In celebration of the first anniversary of the Soviet state in 1918, two monuments completed by Merkurov in 1913 (very good examples of his “academic modernism” style) were selected to be erected on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow: “Statue of Fyodor Dostoevsky” and “Thought.”

The “Monumental Propaganda” program took hold of Merkurov from then on. He began to work on more projects for the cause. Anatoly Lunacharsky, a Russian-Marxist revolutionary and the first Bolshevik Soviet People’s Commissar, even wrote to Lenin about Merkurov and his works: “In my opinion, he is the only artist who is able to satisfy both you and the Moscow workers. He has great power, the ability of psychological analysis and at the same time is realistic.” The letter inspired Lenin to pay Merkurov a visit, where he observed the current project Merkurov was working on, made some criticisms, and had a long conversation with the sculptor about his expectations and desires for the present project, as well as the future.

And so Merkurov became one of the most active propagandists of Lenin’s monumentalism, as well as one of the first sculptor-monumentalists to regularly receive state orders for the statues of Lenin and Stalin — he created a countless number of these statues and monuments.

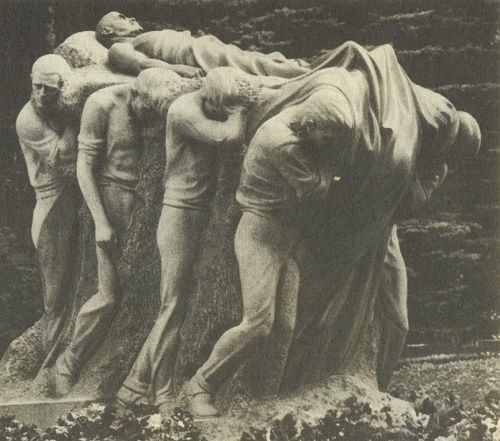

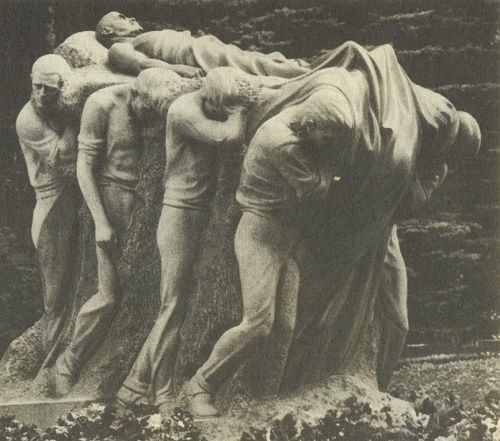

Of significance are Merkurov’s massive works “Shooting of 26 Baku Commissars” (completed in 1946 and installed in Baku — currently demolished) and “Death of the Leader” (completed in 1947 and currently at the Gorki Leninskie Museum-Estate in Russia). Both took over 20 years to complete and are striking examples of Merkurov’s celebrated artistic style and skill.

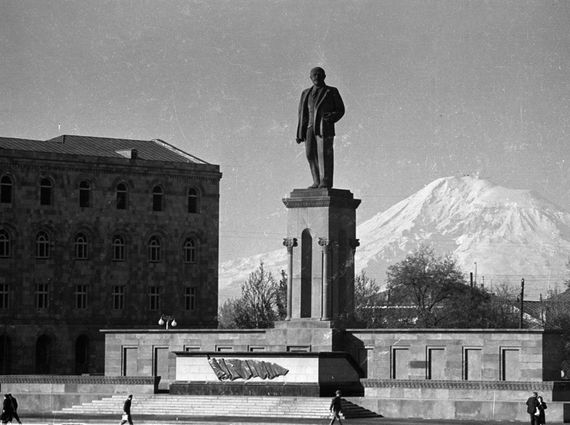

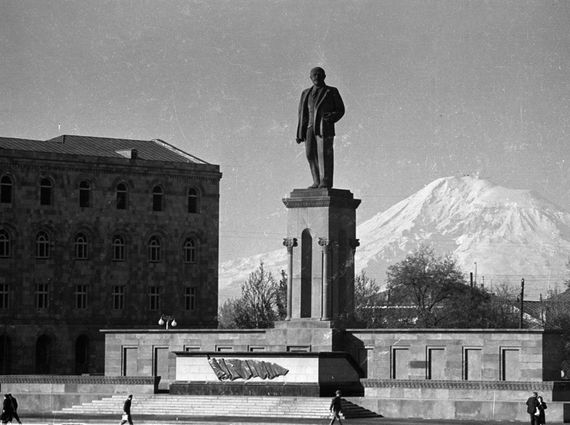

1 – The statue of Lenin at Republic Square in Yerevan.

2- The statue of Stalin at Victory Park in Yerevan.

The monuments that he is most celebrated for, however, are the three largest of Stalin in the whole of the USSR (though today they have all been dismantled). The largest of the three was in Yerevan. It stood in the place of the current Mother Armenia statue, in Victory Park. Measuring in at a height of 49 meters with the pedestal, the monument was erected in 1950, and was awarded the State Stalin Prize of the First Degree in 1951.

The USSR’s second largest statue of Stalin was installed in 1937 as part of a double monument Merkurov created of both Lenin and Stalin. Sitting on the banks of the Volga River, near the beginning of the Moscow Canal in Dubna, Russia, Stalin loomed over one bank, and Lenin the other. Both stood at a height of 37m with their pedestals, and both are the second-largest statues of Lenin and Stalin in the former USSR (the largest of Lenin stands at 57m with pedestal and lies on the banks of the Volga-Don Canal in Volgograd, Russia). After Stalin’s death, the monument was blown up (though a smaller copy, also created by Merkurov, in 1939, can be found today in the Muzeon Art Park in Moscow) but the pedestal remained, as did the statue of Lenin, which can still be visited today.

“Death of the Leader” by Merkurov.

In addition to his statue of Stalin in Victory Park, Merkurov is also the author of many other well-known sculptures in Armenia. One is the the statue of Stepan Shahumyan (1931) which currently sits in Stepan Shahumyan square in Yerevan, and the other is the statue of Lenin, which used to sit in the middle of Republic Square (then known as Lenin Square) before being dismantled in 1991. Erected in 1940 in the center of the capital, today this statue, headless and rusting, can be found laying in the inner courtyard of the History Museum of Armenia.

“Art historians of the era celebrated with respect the ‘Assyro-Babylonian’ power of these monuments,” and it is clear upon viewing any of Merkurov’s monumental pieces that he had a skill for modernizing the powerful “archaic style” of the early civilizations in his sculptural works.

Sculpture, however, was not the only art form Merkurov had a peculiar skill for modernizing.

Merkurov the Preserver of Death and Life

“My entire life, death stood before me in its terrible greatness.” Perhaps it was this fixation on death that made Sergey Merkurov the talented death mask creator that he was.

The tradition of death mask creation finds its roots in ancient Egypt, where a stylized funeral mask was often placed over the mummified body of the deceased (think of the Mask of Tutankhamun). Romans also made death masks, in which they took the form of the face with wax, later using this wax mould as a basis for stone sculptures.

It was not until the late 14th century, however, that the tradition of death mask taking spread to the monarchies of Europe, becoming popular in Russia only in the 19th century. Yet, once it did reach the Russian Empire “masks became an after-death essential for Russian royals and cultural luminaries, including Alexander Pushkin. Lenin’s mummified body… is the most famous example of Soviet post-mortem culture. But the Soviets used death masks to a far greater extent, with the faces of countless Central Committee members preserved in plaster.”

Sergey Merkurov was the preferred death mask taker of the era. With a collection of over 300 death masks, Merkurov is considered the greatest death mask creator of the Soviet time period.

His method was to pour liquid modeling plaster over the face of the deceased. The mould was then removed by a thread that had been strategically placed on the face beforehand. To obtain a cast of the mould, another material could be poured into the mould, such as bronze or copper.

Sergey Merkurov’s first death mask was that of Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian. In 1907 he was called by the Armenian Apostolic Church to Russia for its creation. Three years later he was to be again asked to create a death mask — this time of Leo Tolstoy. Tolstoy’s mask would become the springboard for Merkurov’s death mask career, as one of his best-known works was the monumental death mask-turned-statue of Leo Tolstoy, which shows the writer tucking his hands into his belt like a peasant.

Dmitry Shlyonsky, death mask historian and director of the One Street Museum in Kiev, Ukraine explains that “Merkurov elevated the death mask from a simple mold to an ‘art form…’ After casting the subject’s head, he often transformed the work into a full sculpture, adding hair and clothing.”

Merkurov’s most recognized death mask is that of Vladimir Lenin. As with Tolstoy, Merkurov would go on to use Lenin’s mask as the basis of the many monuments created in the Soviet leader’s image. “Death of the Leader” and a massive Lenin carved in red granite for the 1937 World’s Fair in New York are just two such examples.

Sergey Merkurov would create death masks until his death at the age of 70 in 1952. His own death mask (as well as a mould of his hands) was later taken by one of his student’s. These moulds can be found among the 59 others in his House-Museum.

Though absent from modern memory like many souvenirs from Soviet Union times, Sergey Merkurov and his works undoubtedly played an indelible role in the shaping of both the Soviet landscape and mentality. Today, his surviving works provide a fascinating window into the world of the not-so-distant past.

—————————————–

1 – Tour of Gyumri’s Sergey Merkurov’s House-Museum.

2 – Aslamazyan, M., “Davtar Zhizni: Vvtobiograficheskie Rasskazy” Gyumri – Eldorado, 2016.