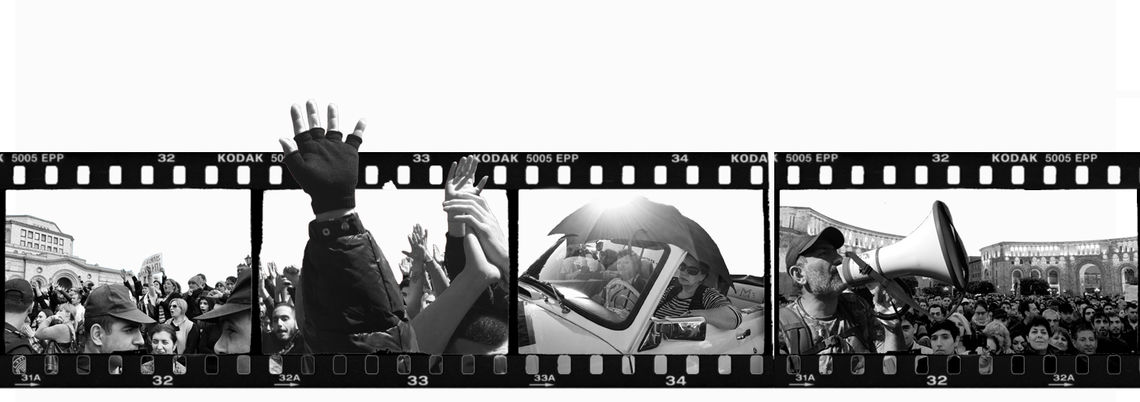

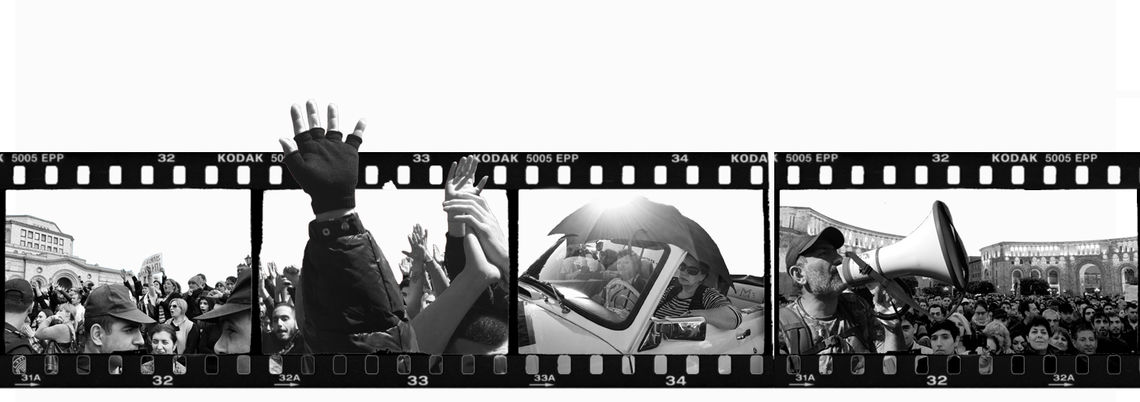

Garin Hovannisian’s “I Am Not Alone” and Bared Maronian’s “Bloodless” both present fascinating views of Armenia’s peaceful Velvet Revolution. Both documentaries, made by diasporan filmmakers, immerse a wider global audience into the events of April 2018. Each film succeeds in different ways, though both shy away from presenting an intricate political view of the events at hand. The Velvet Revolution (or Tavshya Heghapokhutyun) was rightly celebrated throughout Armenia and the diaspora for bringing an end to Serzh Sargsyan’s oligarchic regime.

Hovanissian’s film is the glossier of the two. Produced by a veritable Armenian creative Who’s Who that includes System of a Down’s Serj Tankian, Alec Mouhibian (“1915”), Eric Esrailian (“The Promise”) and Joe Berlinger (“Intent to Destroy”), “I Am not Alone” is a quick-moving, powerful and slick account of events. It’s also a technical tour-de-force, one of the more powerful political documentaries that I’ve seen in quite some time. Hovannisian accompanied Nikol Pashinyan on his 14-day Gandhi-esque walk from Gyumri to Yerevan and his subsequent use of social media to essentially shut down the capital and the existing regime is fascinating in the extreme. The effect of Hovannisian’s technique is to tell the story as if it were unfolding before the viewer’s very eyes: it comes close to illustrating a quote from Jonathan Demme: “It’s a funny thing with documentary films – you want them to feel as entertaining and as gripping as a fictional film. With a fictional film you want it to feel as realistic as a documentary film.” Form and function meld to strong effect and the film builds to a joyous crescendo as Pashinyan meets with Sargsyan to ask for his resignation, before finally being voted into office as Prime Minister on May 8, 2018.

“I am not Alone” also benefits from Barry Poltermann’s seamless editing and a remarkable soundtrack by Tankian. One-on-one sit down segments with Pashinyan and Sargsyan—as well as Yerevan’s surprisingly humane Chief of Police Valeri Osipyan—offer unique insight into the revolution itself and the strategies behind it: “I wanted to create a situation where it’s not the police knocking on the citizen’s door,” Pashinyan explains, “but rather the citizen knocking on the door of power.” We get a glimpse into the mind of Sargsyan as well. Sitting behind a large chess board in a blue suit, he explains that chess “is the fairest game in the world.” On the heels of the 103rd commemoration of the Armenian Genocide, Sargsyan realized that he had been outmaneuvered and ultimately checkmated, and stepped down without a violent showdown. Often accused of political immaturity, the Armenian nation now showed signs of a dawning sophistication.

To his credit, Hovannisian also delves into Pashinyan’s early childhood and his student days as a troublemaker who bristled easily and would not be silenced. Through this early portrait, we come to understand that Pashinyan’s actions in April 2018 were not motivated by political opportunism, but by a deep-seated feel for justice. And yet for all that, we learn too little about Pashinyan’s political views per se, or about his Civil Contract Party. It would have been nice to discover how he diverges from his predecessor on concrete macro and microeconomic policy, but that would be asking a lot of one 93-minute documentary. As with previous peaceful revolutions elsewhere—Czechoslovakia, Tunisia and Lebanon come to mind—the question then becomes: once Pashinyan assume power, will the Velvet Revolution live up to its potential, or would it let down its supporters with more of the same?

Maronian’s Bloodless was made on a smaller budget and proceeds at a slower, more measured pace. His documentary is more classically structured and involves more interviews with talking heads such as EVN Report’s Maria Titizian and United Nations Representative Shombi Sharp. Maronian’s film overlaps with Hovannisian’s in certain aspects and includes much of the same interesting footage and surface analysis of events. “Bloodless” is also likeable because Maronian spotlights the plight of previously-silenced communities in his work. In this case, as in his 2016 documentary “Women of 1915,” he gives voice to Armenian women and lets them speak loud and clear. From the housewives who banged pots and pans out of their windows in support of the protests to those who descended into the streets, to diasporans such as Arsinée Khanjian, women played an important role in the Velvet Revolution.

Bloodless also quite rightly dwells on the role of new technologies and social media in bringing about the downfall of the Sargsyan regime. One of the young women interviewed in the film says that, whenever she became afraid during the street demonstrations, she would pick up her cell phone and get on Facebook, thus becoming a self-appointed journalist. The interesting corollary that is glossed over in both films concerns the relative and corresponding lack of tech sophistication on the part of the Sargsyan administration, which encompassed an older generation. The Armenian government at the time possessed none of the wherewithal of the Chinese authorities, who in the same situation might have quickly cut off all Wifi access in the country. The interviews with activists and repatriated diasporans bring home an important point: namely that all were pleasantly surprised by the youth’s initiative and progressive voices. As Titizian underscores on several occasions, the fact that many of the protesters were just kids—a new generation—bodes well for Armenia’s future and its difficult path toward true democracy. Maronian began shooting “Bloodless” when he heard the early protests outside his hotel window, ultimately putting together an informative and well-structured film.

Both documentaries end their narrative with Pashinyan assuming power. This of course leaves out the very real issues that Pashinyan, a former journalist, would face in actually implementing his democracy-building initiatives during the first two years of his Premiership. Marxist and Freudian historians have been instrumental in pointing out that cultural producers always have an agenda—open or repressed—as well as a critical blindness. The same is true of filmmakers. Though Hovannisian and Maronian have structured their films differently and choose to emphasize different aspects of the Velvet Revolution, both deliver a somewhat hagiographic portrayal of Pashinyan and his supporters. That being said, anyone interested in Armenian politics and the historic events of April 2018 would do well to watch both these documentaries with an open but critical mind.

N.B: The U.S. theatrical release of “I Am Not Alone” has been postponed to late August, pending the pandemic. However, UK/Ireland residents can watch the film on Curzon Home Cinema from May 22-June 5.

Watch the trailers

Bloodless (2020, 94 minutes)

Website: http://bloodless-film.com

You can also sign up to IANA’s email list for news on the film’s release in your area.

Production Company: Armenoid Productions

Director: Bared Maronian

Screenwriter: Silva Basmajian

Producers: Baronian and Silva Basmajian

I am not Alone (2019, 93 Minutes)

Web Site: www.iamnotalonefilm.com

Production companies: Avalanche Entertainment, Serjical Strike Entertainment

Director: Garin Hovannisian

Screenwriter: Garin Hovannisian

Producers: Garin Hovannisian, Alec Mouhibian, Tatevik Manoukyan, Eric Esrailian

Executive producers: Serj Tankian, Joe Berlinger, Dan Braun, Raffi K. Hovannisian, Suren Ambarchyan, Alen Petrosyan

Director of photography: Vahe Terteryan

Editor: Barry Poltermann

Composer: Serj Tankian

Also watch

In 2018, the Armenian people were swept up in a nationwide movement that would come to be known as the Velvet Revolution. Photojournalist Eric Grigorian took thousands of photos, documenting and capturing images of ordinary people who came together to achieve the extraordinary. Through his own words, Grigorian tells the story of the revolution and the moments in-between.