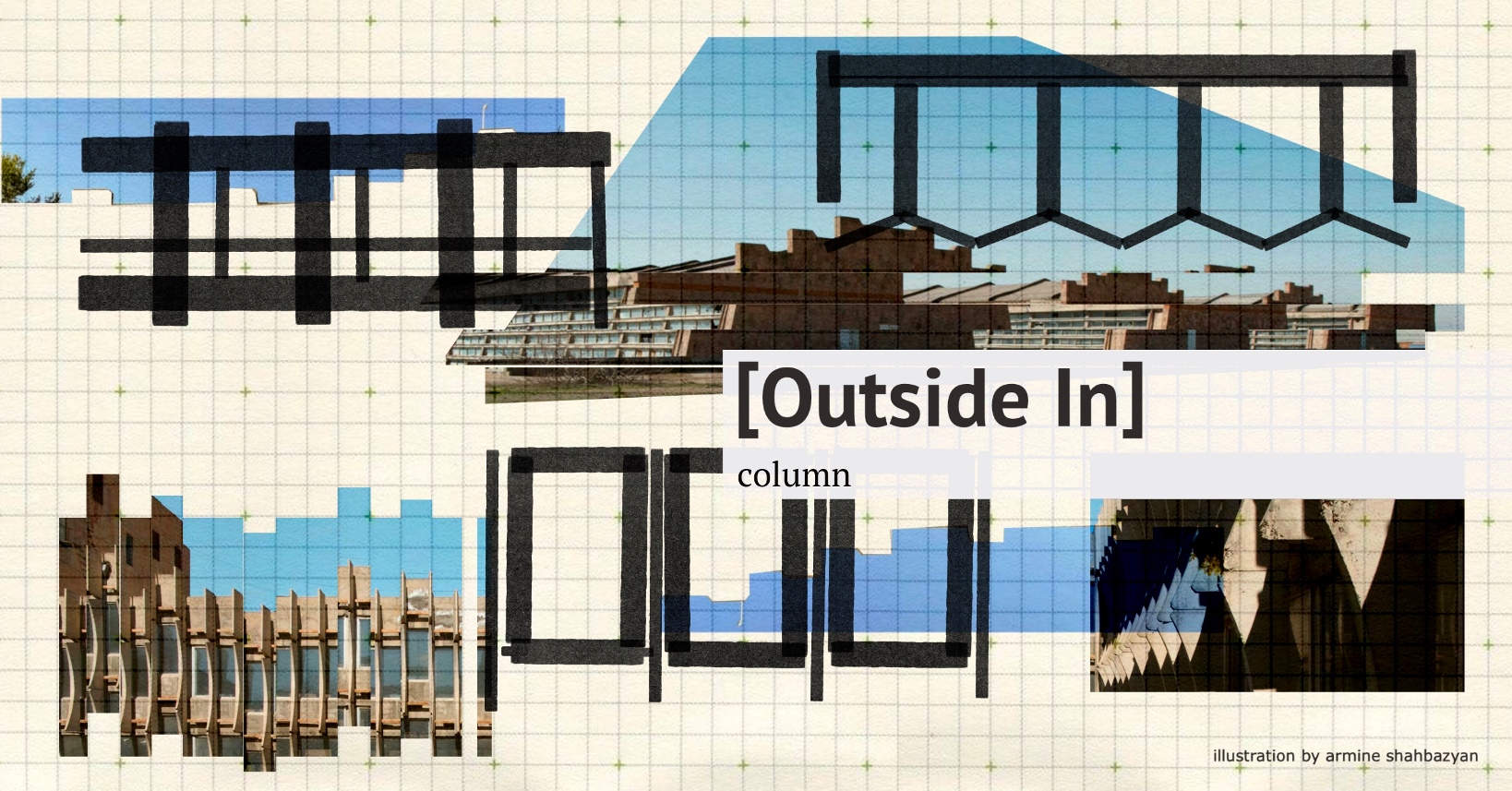

Visiting one post-Soviet state, you can then recognize it in all others – the similar patterns of urban planning and the identical buildings, structures, roads, pipes, wires, tiles, etc. However, an outsider delving inside under the extreme familiarity of the material environment finds an extreme “strangeness” of social interactions and practices. The “Outside In” series is about emplaced paradoxes and nuances. It spotlights the mundane in Armenia’s peripheral locations, where the seemingly unspectacular encounters with people and things allowing us to capture the unique features of the territory.

Listen to the article.

Outside In

Essay 16

There is an intricate connection between literature and urban studies, whereby the former enriches the latter by bringing the subjective, emotional and cultural dimensions of urban life to the fore. For instance, “Our Mutual Friend” and “Bleak House” by Charles Dickens explore themes related to urban social class structures, poverty and inequality in a European capital city during modernity. China Miéville’s novel “The City & the City” describes a case of radical, dystopian segregation, while Italo Calvino’s imaginative “Invisible Cities” allows readers to experience the texture of urban spaces, from bustling markets to quiet alleys, exploring topics such as alienation, community, diversity, stability and change. Through metaphor, hyperbole, or the grotesque, literature animates urban realities, highlighting their complexities or providing glimpses into (im)possible futures serving as a continuous source of inspiration for scholarly endeavors.

Provincial City N and the Zone

After more than a decade of research, I have found that the essence of a typical small city in the post-Soviet realm, with its sociality, materiality and vibe, may be imagined through a combination of four novels. The first is V.S. Naipaul’s “A Bend in the River” which depicts a town in a fictional country on the African continent. Apart from a brilliant description of the “viscous,” slow, and mostly bleak urban social life in a small remote place, the novel also reflects on the post-colonial transition resembling, to some extent, the post-socialist one with the emergence of new economic and power structures. The other three novels, two by Nikolai Gogol and one by the Strugatsky Brothers, come from the post-Soviet region capturing a blend of contextual details.

In “State Assessor” and “Dead Souls” Nikolai Gogol does not provide a portrait of a specific city, but a collective image of provincial city N with its chronic disorder, shared culpability (the untranslatable Armenian word taifabazutyun [թայֆաբազություն] or the Russian expression krugovaya poruka [круговая порука]), and despondency:

The entrance to the city did not make a particularly comforting impression on him. Dirt on the streets, houses that in some places stood tilted… [1]

The official who came from St. Petersburg did not even know where to go out of boredom…

It has become our custom that one thing pulls another along, and together they hold stronger… (Dead Souls).

Our city is a bad one, the roads are dirty, pigs roam the streets… And what are the rules in the city? That is the trouble, there are no rules, there is no order (State Assessor).

The materialities of post-socialist deindustrialization, as well as the spatial and social marginalization it entails, can be imagined through vignettes from the Strugatsky Brothers’ “Roadside Picnic”. The novel revolves around the Zone, a site of alienation where an extraterrestrial visit took place:

Why is there no smoke over the factory? Is there a strike…? Yellow rock cones, blast furnace air heaters shine in the sun, rails, rails, rails, a train with platforms on the rails… Only there are no people. Neither alive nor dead…

It is filled with enigmatic, oftentimes deadly substances and objects that are snatched out by stalkers, people who trespass into the forbidden area:

They carry out everything they can from the Zone: empties, black sprays, witch’s jelly, bracelets, slot machines, eternal batteries… No one knows what these things really are, what they are for, or how they work. Sometimes they turn out to be incredibly useful, sometimes—incredibly dangerous (Roadside Picnic).

This is your average, “local” small post-Soviet city, a space of chaotic and disorderly post-socialist transformation. Its residents face deprivation and scarcity, unemployment, and sudden poverty. Some resort to DIY projects and semi-legal activities, others seek remedies in alcohol and drug abuse. Urban spaces are crumbling because of insufficient funding, as well as issues with responsibility, accountability, and quality control. Scattered throughout are fenced-off, restricted former industrial grounds, now zones of alienation, occasionally visited by dark tourists and the new foragers (or looters). Yet, every rule has an exception. Some small cities defy these conditions with unexpected vibrancy and call for different references and parallels. One of them is Metsamor.

Metsamor As Foundation Pit and Beyond It

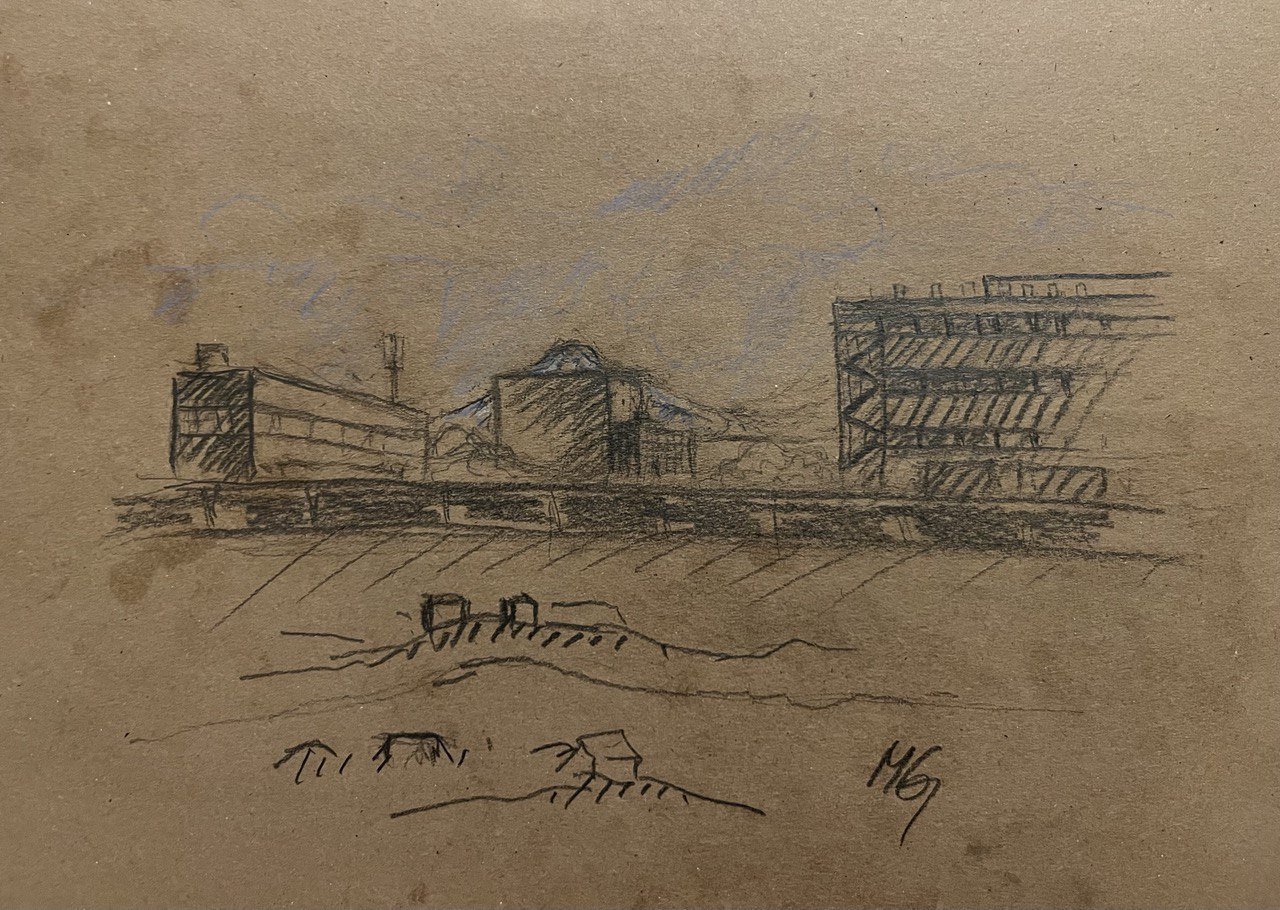

In March 2022, I set on a journey to find a field site in Armenia for my doctoral thesis. Through various means and media, I was striving to encounter a “properly empty place”—one with dispersed spatialities, uncertain temporalities, and material manifestations of decay, i.e. suitable for the “Emptiness” project of which my thesis is a part. My first choice fell on Metsamor,[2] the “satellite town” of the Armenian Nuclear Power Plant designed from scratch under the guidance of Martin Mikaelyan, renowned master of Armenian high modernism.[3] Construction of Metsamor began in late the 1960s to accommodate workers for the nuclear power plant. Following the Spitak earthquake, the plant was shut down in 1989, halting further development of the town. The severe energy crisis of the early 1990s forced the Armenian government to restart the plant, restoring Metsamor’s original raison d’être. However, this did not lead to renewed funding for the town’s unfinished construction.

The trip to Metsamor from Yerevan takes around 40 minutes through the Ararat Valley, mostly flat, dry and dusty in sepia hues. Though on a clear day one can enjoy the gorgeous view of Mount Ararat. The entrance to the city is unremarkable, except for the predominantly vacant check point, a remnant of the Soviet state’s tight control over places with strategic industries. For someone like myself, who grew up in a (post-)Soviet nuclear town, Metsamor feels strikingly familiar, etched into memory through its numbered microdistricts, Brezhnev-era prefab housing, absence of street names, and even the large square tiles with their diamond pattern. Yet, it is unmistakably Armenian, with its orange-hued tufa buildings, pulpulaks, occasional architectural details adorned with national motifs, and the unmistakable presence of Armenian-language inscriptions.

The city’s most remarkable landmark and the main tourist attraction lies on its outskirts, the emblematic Metsamor Sport Complex. Best described as “three pyramidal structures”[4] with ribbon-like glazing, it houses two swimming pools, a gym, and a basketball court. The sports complex is closed off and guarded, partly functional, partly abandoned as evidenced by the shabby pools and broken windows through which I attempted to enter but after a thorough analysis of the passage, gave up. At the back lies an artificial pond that was filled with water only once. Now it is empty and grass sprouts through the cracks in the concrete. The cherry on top is the observation deck above the pond which offers views to both the nuclear power plant and Mount Ararat.

Walking back from the sports complex without any particular destination in mind, I wandered through the yards with their lines of laundry and flower beds, walked the passages connecting residential buildings with their snaky wiring and hectically arranged pipes. Finally, I exited this labyrinth to see the municipality building from the back with a large, fenced foundation pit that immediately sparked allusions to the eponymous novel “The Foundation Pit” by Andrei Platonov. The novel tells the story of workers digging a massive foundation pit for a future building meant to symbolize the construction of a socialist society. As the story unfolds, it becomes apparent that progress on construction is slow, the workers suffer from the pointlessness of their own labor, and the vision of a bright future becomes increasingly vague. In the end, the project remains an unfulfilled utopia. The novel is a philosophical and grotesque reflection on the Soviet modernization project, exposing its futility and destructiveness to individuals. Beyond being a mere historical document of the Soviet era, “The Foundation Pit” is a universal parable about the dangerous nature of utopias that seek to forcibly reshape the world, disregarding the value of human life and freedom.

As argued by social anthropologist Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov, the dramatic end of the Soviet Union which was “forever until no more,”[5] should not obscure the fact that it was not a single state project, but a series of projects. Each of them had different lifespans and scales, where failure was a constant and recognized part. Thus, Metsamor at first glance is yet another kisakaruyts [կիսակառույց] or nedostroi [недострой], a distinctive (post)Soviet type of ruin—unfinished construction and failed visions. In the words of visual artist Katharina Roters and architect-urban planner Sarhat Petrosyan, the city is a superimposition between utopia and collapse, whereby only one or the other can be seen at a particular point in time. And while I agree with these two grand narratives being present, there is something else to Metsamor that does not fit neatly into the dichotomy.

The city’s social and economic center emerged along the main road next to the municipality building, shifting from its originally planned location near the unfinished microdistrict. In place of the monument commemorating the peaceful atom, a church now stands. Densifying the courtyards sunken in greenery, numerous garages and outbuildings have been constructed along with housing extensions that serve as additional residential space or host commercial activities. Amid these structures children play and elderly residents engage in conversations while young adults work or run on errands. Fruit trees and flowers add color and vigor to the cityscape. Metsamor is bursting with life. It is, perhaps, less grandiose and orderly as envisioned by its creators, but evidently on a human scale. The unplanned but organic transformations—fuzzy and creative—are testimonials to the ever-changing nature of cities, to the adaptability and agency of residents. The actual existing Metsamor is a novel that should be read between the lines of rigid form, omitting popular imaginaries and conventional metaphors. Its essence is traced through the entangled footnotes and unsequenced handwritten comments on the margins.

Drawing by Maria Gunko.

Footnotes:

[1] All translations from Russian are mine.

[2] Idea was abandoned due to an unpleasant encounter with local security forces which included interrogation, search through belongings, and accusations of being an alleged Azerbaijani spy. Piece of advice, do not come close to the power plant or take any detailed pictures.

[3] An in-depth historical and architectural reference, notes on everyday life, as well as abundant visual material may be found in “Utopia & Collapse, Rethinking Metsamor: The Armenian Atomic City” (2018), collective monograph edited by Katharina Roters and Sarhat Petrosyan.

[4] Roters, K., Petrosyan, S.,“Utopia & Collapse, Rethinking Metsamor: The Armenian Atomic City” (2018).

[5] Yurchak, Alexei,“Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation” (2006).

See all [Outside In] articles here

Maria Gunko is a DPhil Candidate in Migration Studies, Hill Foundation Scholar at the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography University of Oxford. Since 2023, she has joined Yerevan State University as a Visiting Professor. Maria holds an MSc and Kandidat Nauk (Russian post-graduate degree) in Human Geography.

Maria’s research interests lie in the intersection of urban studies and social anthropology, including ethnography of the state, infrastructures, and urban decay with a geographical focus on Eastern Europe and the Southern Caucasus. She is the co-editor of one monograph, author of over thirty scientific articles and op-eds.