“There are no certainties in life except for death and taxes.” The expression is likely familiar to most, but makes a succinct emphasis on a matter that always and everywhere touches a certain nerve with the public.

Using an economic framework, the value created in a country, measured by the Gross Domestic Income (GDI), a complementary indicator to GDP, is usually split among three stakeholder groups:

– the capital-owners that take risk, invest their savings and hopefully reap the benefits of their endeavors in terms of profits, dividends and interest income;

– the labor, that contributes time and effort and is remunerated for such, and

– the government that collects taxes and fees from the above two stakeholder groups from the value they have generated in their activities.

Armenia Post “Velvet Revolution” and the New Tax Reform

Before the political disruption in 2018, the economic and reform dynamics in Armenia did in fact resemble the patterns above. The country showed chronic budget deficits, debt accumulation as well as excessive negative savings rates (i.e. when consumption is above production in an economy) not to mention the unsatisfactory reform process.

More specifically:

– Budget deficits were running at 5 percent (2015-2017),

– Public debt, at 60 percent of GDP in 2017, was reaching an officially self-imposed debt ceiling,

– Total External debt was above 90 percent of GDP (2017), while

– The Trade balance, an indicator of the imbalance between national Production and Consumption, averaged at -12 percent of GDP (2015-2017).

Given the above, there are certain points that can be made when evaluating the tax reform proposals of the new RA Government. Obviously with the important caveat that the laws are at a draft stage and likely to be modified going forward. Another point to mention, before offering some comments, is that the Government may in the near future implement additional policy adjustments that are not yet public (e.g. related to mandatory pensions). These can of course have complementary effects to the tax reform. All in all, one should be cautious in making long going predictions at this juncture.

To summarize the main points of the new tax law, one can say that the draft leans heavily towards tax synchronization as well as lowering of income and corporate taxes. Simultaneously, it uses higher excise duties (e.g. duties on tobacco, petroleum) and expectations of higher tax revenues (presumably from lower shadow activity and higher economic growth) to cover the likely budgetary shortfalls.

In light of the previous, below are some comments on the issue:

– The Government will surely have run the numbers on likely revenue shortfalls from the tax cuts and potential revenue gains. Yet given the broad public mandate the new Government enjoys, maybe it would be more advisable to abstain from tax cuts and address the deficit/debt issues if the expected revenue increases do indeed materialize.

– Connections between corporate tax reductions, higher investment and economic activity have historically tended to be spurious. The reduction in personal income taxes for households, will surely boost short term economic growth but will do little else with regard to structural deficiencies. In fact consumption and imports will likely rise and aggravate the consumption-production imbalance.

– Moreover, Armenia does need to see through substantial amounts of (currently debt financed) military technical modernization, reverse the previously falling levels of educational expenditure, boost infrastructure investment and continue the financial aid to Artsakh. Again for the more risk averse, using the expected higher tax intake for these purposes would seem more sensible.

– There is also the issue of the “inclusive growth” that is said to be prioritized by the Government. To be frank, the terminology is new and while one can sense a certain amount of liberal thinking (i.e. individual effort and responsibility for success) behind official statements, it is difficult not to build-up expectations of less inequality in society. And inequality has usually and most effectively been tackled in countries with highly redistributive fiscal policies (i.e. high personal tax levels overall and unambiguously high marginal tax rates.)

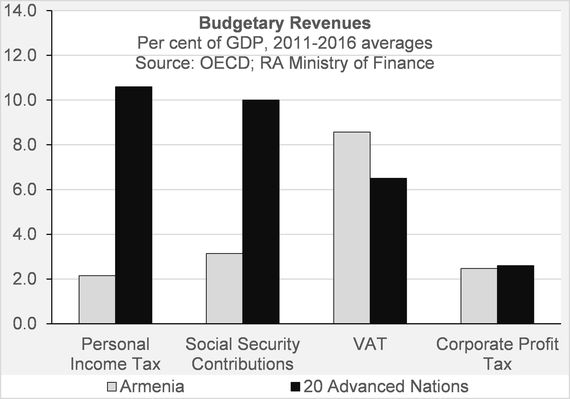

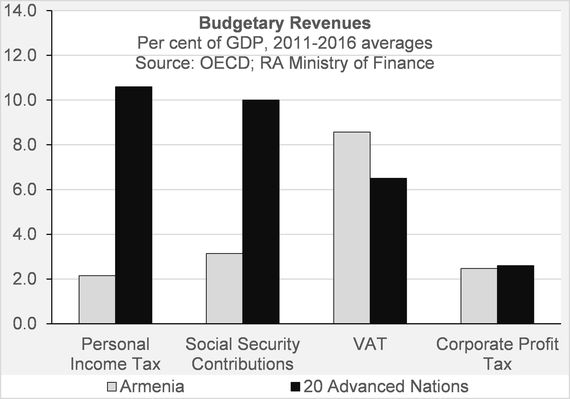

– Finally and for reference, Armenia’s tax environment is already not overly burdensome, at least when considering tax levels and ignoring the administrative hassle from previous frequent changes to the tax laws. In fact, in many cases, especially on the personal and social security side, Armenia lags significantly to its richer country peers. While one might argue that Armenia’s fiscal metrics should be instead compared to those of developing countries, the picture would only change on the margin, that is the gaps between Armenia’s number and those of its peers would only be slightly smaller. Secondly, the above should provide a sense of direction that Armenia needs to take when it comes to fiscal revenue levels and structure of financing sources.

To summarize and volunteer a proprietary vantage point, it is difficult to enthusiastically endorse the draft tax package currently on the table. The debt/deficit issues, financing requirements and the advanced country road-signs point in a somewhat different direction. The strong mandate and trust the Government enjoys could have been used to manage society’s expectations that the extra revenues are indeed necessary, will be spent transparently and serve the collective needs of society for the national interest. While somewhat of a politically complicated step to take, the public at some point needs to become informed enough to accept the trade-offs. The Prime Minister’s recent statements that accentuated the financing needs for new infrastructure projects and the difficult trade-offs that need to be made, seem to acknowledge the delicate balances noted above.