The Diaspora has been an inherent component of Armenian reality since antiquity. Its enduring roots, affluent heritage and indispensability to the Armenian nation is difficult to challenge. On the other hand, the diverse socio-economic tendencies prevailing in Armenia and globally, augmented by uncertainties have led to the active pursuit of new development tools by many countries. This article will examine the global entrepreneurial endowment of the Diaspora, how it developed and what its role can be today.

Post-Independence

The pattern of Diaspora involvement in Armenia’s economy following the establishment of the Republic of Armenia in 1991 has gone through several phased developments.

The Diaspora acted as the first generator of investments in the newly independent Republic of Armenia. In the early period, it was predominantly sporadic charitable contributions that were provided to the newly established Armenian state undergoing difficult times. Eventually, the Diaspora involvement became more structured with a range of platforms set to enable economic relations with Armenia (e.g. the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund). However, in the 1994 – 2000 period, the poor image of the political and economic regime in Armenia had negative consequences on Diaspora engagement.

The beginning of the 2000s sparked a new wave of involvement of Diaspora investors in Armenia’s economy. A chain of events such as the celebration of the 1700th anniversary of the adoption of Christianity as the state religion and a series of Diaspora-Armenian events (Pan-Armenian games, Investment Conference in NY, Diaspora-Armenia Economic Conference, etc.) fostered Diaspora-Armenia investment relations. On the other hand, income growth in Armenia, enhancement of infrastructure and expanding export opportunities attracted a growing number of Diasporans to invest in the Armenian economy. Diaspora-leveraged deals started to emerge including attraction of multinational corporations (MNCs). The ‘usual suspect’ sectors attracting Diasporan investments included information technologies and communication, jewelry-making and diamond-cutting, food processing, construction, textile and apparel.

The beginning of the 2000s sparked a new wave of involvement of Diaspora investors in Armenia’s economy. A chain of events such as the celebrations of the 1700th anniversary of the adoption of Christianity as the state religion and a series of Diaspora-Armenian events fostered Diaspora-Armenia investment relations.

Antiquity

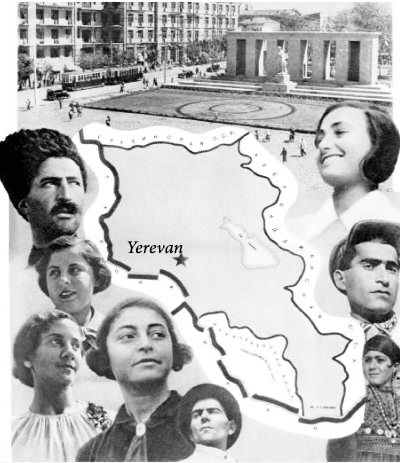

The Armenian Diaspora has existed since time immemorial, and it would be a futile attempt to accurately trace it back. Constant travelling and migration has long been in the Armenian gene.

During the reign of Tigranes the Great in the 1st century BC, while Armenia was continually expanding, Armenians were moving along and settling down in distant regions including places, where centuries later, a new Armenian kingdom – Cilicia – would be established. Armenian communities increasingly started to emerge outside of Greater Armenia, in the Persian and Byzantine Empires.

In medieval times, the decline of Armenian kingdoms and subsequent occupations by Byzantine, Persian, Arab, Seljuk, and Mongol empires triggered emigration from the Armenian Plateau and led to the emergence of organized forms of the Diaspora. Structured Armenian communities developed in distant locations stretching from India and Iran to Ukraine and Poland to Italy.

Armenians played a pivotal role in different empires including overseeing the Eurasian silk trade in the Safavid Empire in the 16-18th centuries and acting as the main financiers of the Iranian Shahs. Armenians also assumed a major role in external trade of the Ottoman Empire.

Standardized organizational configurations surfaced in Diasporan communities – schools and churches – that would act as mighty footholds for the nation throughout centuries.

19th Century and the Aftermath of the Genocide

In the 19th century, atrocities committed against the Armenians within the Ottoman Empire along with the advancement in transport infrastructure accelerated long-distance emigration. The barbaric events of the Armenian Genocide executed by the Ottoman Turks in 1915 set off massive forced displacement and irreversibly reshaped the Diaspora’s development trajectory.

The post-Genocide period witnessed the transformation of the Diaspora in the form of transatlantic emigration. Transitional migration flows began whereby certain countries (e.g. in Middle East) would act as temporary hosts to facilitate further migration and with final destination in Western countries.

The 20th century also recorded mass repatriation from various communities in the Diaspora to Soviet Armenia in the aftermath of World War II and the reverse – emigration from Soviet Armenia to the United States starting in 1970s.

An Eye to the Future

Recent years have been marked with a new level of Diaspora-driven brain circulation and value generation in Armenia. The country is witnessing seeds of repatriation from Russia, USA, and Canada. Syria is a case on its own fueled by the atrocious geo-political situation ruling in the country.

Today more than ever, Armenia needs to deal with its relations with the Diaspora and reengineer its future trajectory. The increasingly difficult challenges in the country leave no room for alternatives. Globally, Armenia has the fourth highest proportion of its population born in the last quarter-century living outside of their country of birth – a daunting one-quarter.

On the global side, things are becoming more unforeseeable in a number of countries across the world ranging from Trump-led U.S., crisis-inflicted Russia, and a disintegrating Syria.

Armenia needs to provide bold answers to a set of dubious questions such as whether it can act as a safe and alternative haven for the thousands of Syrian-Armenians having fled to Armenia. Otherwise, it’s going to be a stopgap for masses prior to re-emigrating to the West as we are seeing today.

The fruitful diaspora experience of other countries makes one ponder (e.g. GlobalScot for Scotland) what Armenia could do next. The Diaspora can be a transformational force for Armenia and constitute the backbone for non-linear development.

The coherent sequence of actions would be to mitigate further emigration up front. Then direct intra-country emigration of Diasporan Armenians to the motherland. Syria is a leading case; Middle Eastern communities of Iran and Lebanon can well come out on the next page.

By the end of the 2000s, the economic involvement of the Diaspora was significantly impeded due to major shortcomings in Armenia’s business environment and the global financial crisis. The impact was particularly vivid in the construction sector. Currently, the euphoria regarding an independent motherland has been fading away and pragmatic business interests have taken over.

Regarding Diasporan investments, while ‘ethnic discount’ (acceptance of lower rate of return or higher risks on investments in Armenia due to the ethnic identity) has been a big factor in the post-independence era; the euphoria regarding an independent motherland has been fading away and pragmatic business interests have taken over.

Armenia and Diaspora mutually need each other and there is no other option. Faced with grave security menaces and swelling demographic challenges, Armenia needs to reengineer the country model for survival and evolution. To this end, the Diaspora can expedite the development of a novel model of sustainability.

Throughout centuries, the key to the Armenian Diaspora’s success has been its talent to adapt to and embrace local culture in host countries while strongly preserving Armenian identity. The Diaspora has also fostered and transmitted its entrepreneurial spirit through generations.

What makes the Diaspora such a powerful configuration and prosperous in host countries?