In the days leading up to the official start of campaign season the Armenian parliament failed to adopt changes to the country’s Electoral Code. The proposed amendments called on the election of deputies to the National Assembly solely based on a party list, instead of the two-tier proportional system that included the ‘rating’ or open list method. Other proposed changes included the lowering of the electoral threshold from five percent to four percent (for political parties) and from seven percent to six percent (for PECs). The amendments failed largely due to the lack of support from RPA members of parliament. Herein we witness another miscalculation by the RPA. The party believed that its chances of winning parliamentary seats was higher with the rating method than the party list method. Ironically, the RPA ended up receiving 4.7 percent of the party list vote. Had the RPA supported the amendments (which lowered party list inclusion to four percent), they would have been included in the new parliament!

In developed countries, partisanship and electoral party support is based on issue convergence, or the proximity between the party’s issue positions and that of the voter. In the developing world, partisanship and electoral party support is based on clientelism. In Armenia, we witness a distinct form of clientelism, that of patronal voting.

Prior to the start of the electoral season, which, per Armenia’s existing Electoral Code, were slated for November 26, the RPA accused Pashinyan of misusing the office of the Prime Minister by engaging in early campaigning. Pashinyan, in his role as acting Prime Minister, held rallies in several Armenian villages and cities prior to November 26, which the RPA qualified as violations of electoral laws. Continuing, the RPA launched another complaint against Pashinyan, this time accusing him of hate speech. The specific example RPA members alluded to occurred on November 27 at a My Step rally in Gyumri, where Pashinyan threatened violence against RPA members “by laying them on the asphalt.” While Pashinyan did not allude to specific RPA members, his rhetoric was aimed at the elite whom he accused of systemically depleting the country’s resources for personal gain.

If you are concerned…vote RPA.

If you are concerned…pay up.

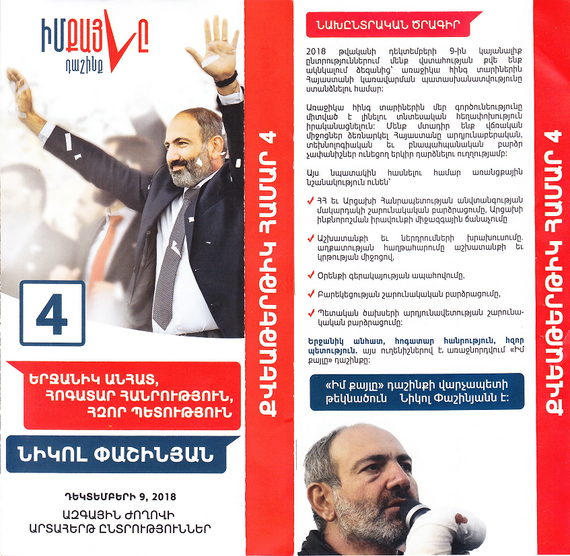

My Step campaign brochure.

Bright Armenia campaign brochure.

The “If you are concerned…vote RPA” campaign was quite an odd campaign message. First, the message did not parallel the mood of the country. Generally, Armenian voters were quite jubilant and optimistic about the upcoming elections and Armenia’s future. While prior to the Velvet Revolution the Armenian electorate was among the most pessimistic in the Caucasus, the aftermath of the revolution brought about optimism and hope in the mindset of the median Armenian voter. Moreover, because the so-called issues of “concern” were topics that Armenian voters were relatively unconcerned about, the message of concern failed to connect with the average voter. Further, the availability of social media created obstacles for RPA’s message. Almost instantly after the campaign message was publicized, Armenian voters took to social media to mock the RPA message through dozens of memes. The message (‘If you are concerned…pay up) has been revised to note the anecdotal evidence of Serzh Sargsyan’s brother as a nationwide extortionist. The abundance of such memes delegitimized the importance of the message. Contrary to RPA’s “doom and gloom” campaign, My Step PEC presented a message of optimism primarily centered around Pashinyan. The campaign slogan was “A happy individual, a caring society, a powerful state.” The two slogans could not be any more different: RPA presented a sense of concern and pessimism, while My Step presented optimism and strength.

At the onset of the campaign season, My Step’s strategy focused on the personality of Pashinyan and his populist rhetoric that was more about seeking justice against the corrupt elites of the previous regime. A typical My Step campaign rally began with a brief discussion of an issue (usually a valence issue, that is, an issue in which there is consensus about its position, such as water scarcity) that was important to that specific village or city. This was then followed by the populist rhetoric of Pashinyan dishing out verbal justice against the past ills of the elites. In retrospect, the average Armenian voter reacted more to the rhetoric than to the policy.

Compared to My Step PEC, BAP’s campaign centered more around the political, social, and economic issues facing the Armenian voter. Lacking a Pashinyan-esque charismatic leader, the BAP relied on the cool and collective image of its two main leaders, Edmond Marukyan and Mane Tandilyan. BAP’s political message paralleled that of My Step, an optimistic and joyful period for Armenia. BAP’s leadership team and issue-centric message was evident in its campaign flyers. Whereas, Pashinyan takes center stage in the My Step flyer, the BAP flyer provided a thorough breakdown of its policies in various issue domains, something missing in the My Step campaign message.

The Transformation of the Armenian Voter

The post-Soviet Armenian voter is considered relatively apathetic about the significance of the political process and economically pessimistic about their and the country’s overall economic perspective. Past sociological surveys have found Armenians to be the most pessimistic about trusting their political institutions and the electoral process.

In 2017, the Armenian Election Study (ArmEs) became the first scholarly-driven voter behavior survey that gauged the political behavior of the Armenian voter. The March 2017 pre-electoral survey was conducted in the weeks leading up to the 2017 parliamentary election. The results added further evidence about the ‘withdrawal’ syndrome of the Armenian electorate. Leading up to the December 2018 parliamentary elections, the ArmES research team conducted its second wave aimed at revisiting the originally sampled households to measure changes in the political behavior and public opinion. The 2018 survey concluded on December 8 with a sample of 1,128 households across Armenia. The 2018 results point toward a transformation of the Armenian voter.

Issues

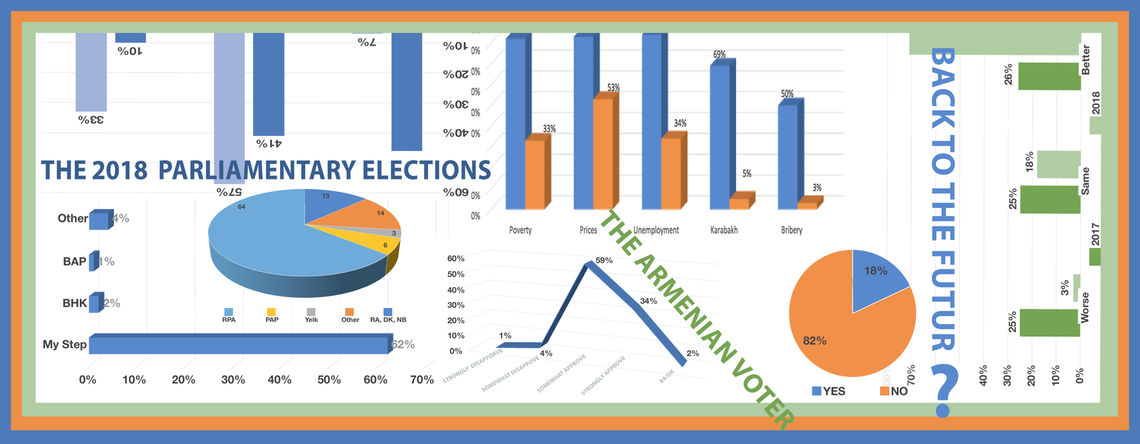

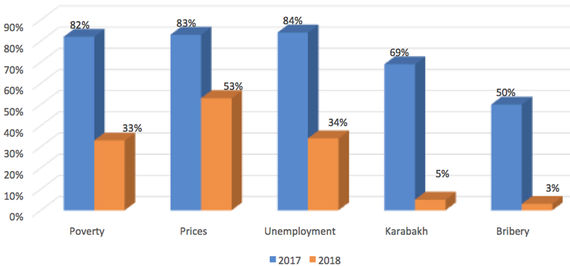

Prior to the Velvet Revolution and on the eve of the April 2017 parliamentary elections, the Armenian voter provided a gloomy picture of political, social, and economic changes within the last twelve months. When asked Compared to last year, how do you think the situation has changed in Armenia? the Armenian voter overwhelmingly responded with a negative retrospective judgment. Eighty-two percent said poverty was worse in 2017 than 2016; 83 percent said prices were worse in 2017 than in 2016; 84 percent said unemployment was worse in 2017 than in 2016; 69 percent said the Karabakh conflict was worse in 2017 than in 2016; and 50 percent of respondents said that bribery was worse in 2017 than in 2016. The negative retrospective evaluation of the five salient issues was not surprising. Economically, poverty and unemployment were widespread, and prices were controlled by oligarchic enterprises. Socially, bribery was the method by which formal transitions between agents of the government and its people were taking place. Politically, Armenia and Artsakh had lost 800 hectares of land during the April 2016 war. Overall, this retrospective analysis of the five issues provided a pessimistic outlook of the Armenian voter.

In 2018, the Armenian voter found itself in much more favorable conditions. The 2018 ArmES noted the overall optimism of the Armenian voter. When comparing the questions above in 2017 and in 2018, it becomes clear that the Armenian voter is generally more optimistic about the last 12-month period. Relatively speaking, all five issues witnessed a significant drop in the number of respondents who perceived the issue being worse off. For example, the issue of prices witnessed a drop from 83 percent to 53 percent; poverty witnessed a drop of almost 50 percentage points. Perhaps the two most extreme cases of change was the issues of Artsakh and bribery. In 2018, only 5 percent of voters disclosed the Artsakh issue as being worse today than in 2017. And just 3 percent of voters disclosed bribery as being worse off today than in 2017. Overall, the descriptive data points toward a public that is relatively optimistic about the five salient issues.

Economic Perceptions

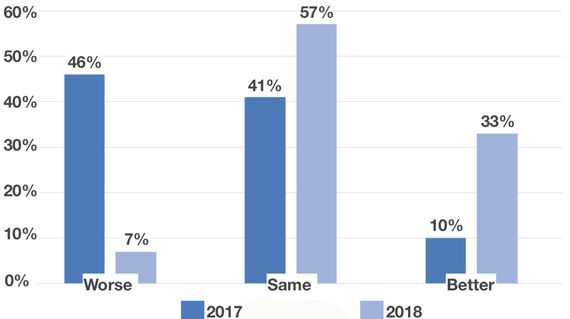

Aside from measuring how Armenians perceived changes in political, social, and economic issues, ArmES also gauged the economic perceptions of the Armenian voter. Economic perceptions is divided into two dimensions. The first deals with time-period. Voters are asked retrospective questions and prospective questions. The second dimension deals with the spacial aspect of the economy. Voters are asked pocketbook questions and sociotropic questions. The former measures changes in their personal (or household) economic situation, while the latter measures changes in the country’s economic situation. In 2017 and 2018, the Armenian voter was asked a retrospective-sociotropic question: Looking back, how do you rate the following compared to 12 months ago: economic situation of the country?; and a prospective-sociotropic question: Looking ahead, do you expect the following to be better or worse: economic conditions in this country in twelve months?

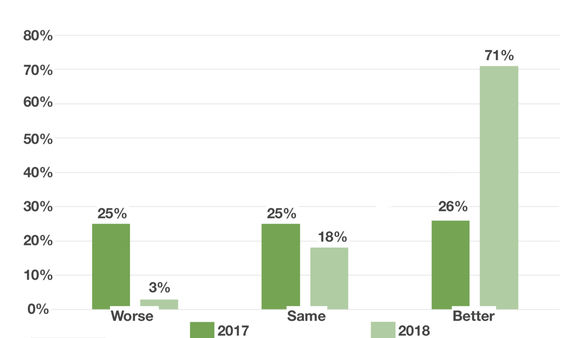

Empirically, prospective attitudes are more likely to witness positive responses. Thus, the higher percentage of a positive wellbeing in a prospective vis-à-vis retrospective judgement in both 2017 and 2018 is in accordance with conventional theory.

That said, we notice a clear positive change in the amount of individuals that reported being worse off in both dimensions across the two years. In 2017, 46 percent of Armenian voters disclosed the country’s economic state being worse off than in 2016. That number dropped to just seven percent in 2018. A similar trend is evident in prospective-sociotropic perceptions.

Percentage of Respondents who Disclosed the Issue Being Worse Today (than the previous year)

Retrospective-Sociotropic Attitudes

In 2017, one-fourth of the Armenian electorate reported that the economic situation would deteriorate in the next 12 months. In 2018, only three-percent of respondents disclosed that perception. Finally, we witnessed a significant increase in the percentage of respondents who are optimistic about the country’s economic future. In 2017, just 26 percent of individuals believed the overall economy would be better in a one-year period.In 2018, that number increased to 71 percent! Overall, the descriptive evidence points toward an Armenian electorate that is more optimistic about future economic changes.

Partisanship and Elections

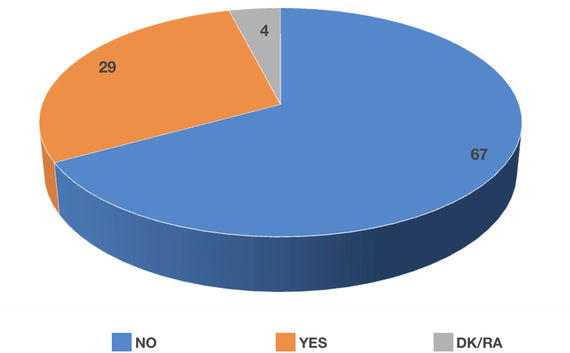

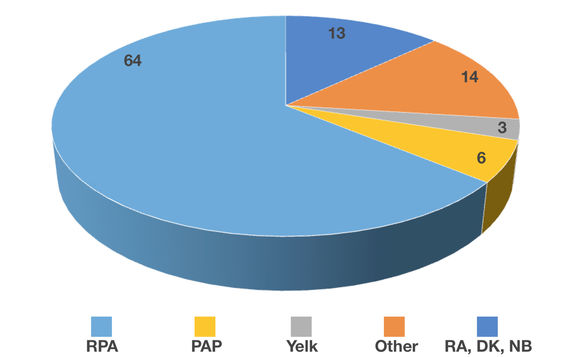

The Post-Soviet space is notable for its lack of partisanship and in Armenia we witness the minimal role that party identification plays in shaping the electoral behavior of the Armenian voter. In 2017, ArmES asked Armenian voters if they feel close to any particular political party? Two-thirds of Armenian voters responded in the negative. Only 29 percent of Armenian voters disclosed party identification. The distribution of partisanship among such voters favored the PAP and RPA. Specifically, of the 29 percent that identified themselves as partisan, 38 percent identified with PAP, 30 percent identified with RPA, and 6 percent identified with Yelk. The single digit support for Yelk, a political bloc that included what later became My Step PEC and Bright Armenia, was not surprising as Armenian voters were patronal voters. That is, they identify and support the party from which they can engage in upward socioeconomic mobility. In developed countries, partisanship and electoral party support is based on issue convergence, or the proximity between the party’s issue positions and that of the voter. In the developing world, partisanship and electoral party support is based on clientelism. In Armenia, we witness a distinct form of clientelism, that of patronal voting. The electorate sided with the RPA and PAP because of a familial or relational proximity with the party, which then helps them further their economic mobility. This then creates a wider patronal network around each party.[2]

The 2017 ArmES posed a vote intention question that asked voters If the April 2017 parliamentary elections were held tomorrow, what party (or alliance) would you vote for? Here we witness further evidence of political apathy as the majority of the respondents either refused to answer, did not know, or intended to vote for nobody. Of the parties and alliances listed on the 2017 ballot, approximately 15 percent of respondents intended to vote for PAP; 13 percent intended to vote for RPA; and 3 percent intended to vote for the Yelk Bloc. The fact that the PAP led the RPA in vote intention should not be interpreted as a statistical inference. This descriptive figure discounts the majority of voters who chose not to provide an answer in the affirmative. What the vote intention questionnaire does entail is the larger disengagement of party support on the part of the Armenian voter.

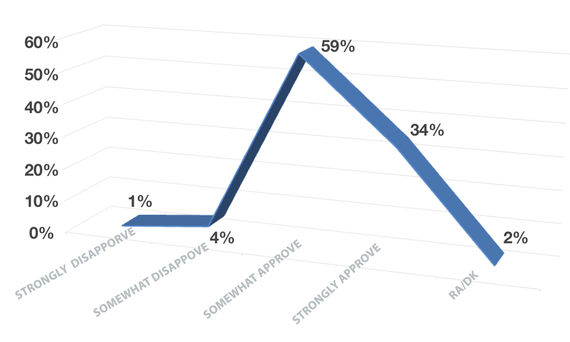

The 2018 snap parliamentary election provided a distinct playing field to measure political behavior and public opinion. Widespread support for Pashinyan was recorded in the second wave when 93 percent of respondents disclosed either somewhat approval or strong approval of the way Pashinyan is handling his job as Armenia’s Prime Minister. This questionnaire provided a heuristic in terms of the support his party would obtain.

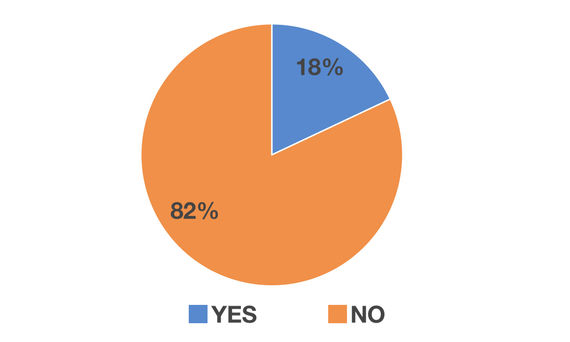

The decline of the RPA and the ascendance of My Step as the new party of power may result in the decline of Armenian partisanship. Since the RPA is no longer at the helm of political power, many patronal voters now will no longer identify with the RPA. At the opposite end, such voters have yet to receive patronage from My Step and thus are still at the sidelines about identifying with My Step. The descriptive results from the partisanship questionnaire may point to this exact trend. From 2017 to 2018 we notice a decrease in party identification of approximately 11 percentage points. The reason for the drop can be due to either the exodus of the RPA or the social desirability effect of RPA partisanship. The latter would suggest that the 11 percent decrease in partisanship across Armenia is mainly due to the unpopularity of feeling close to the RPA. Thus, past voters who identified with the RPA are no longer partisan RPA members solely because it is socially undesirable to do so.

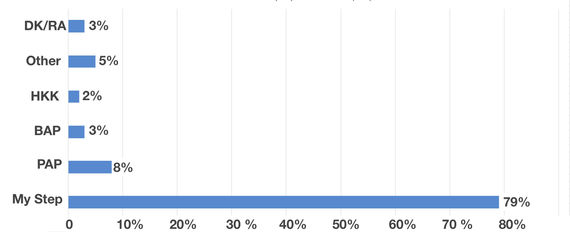

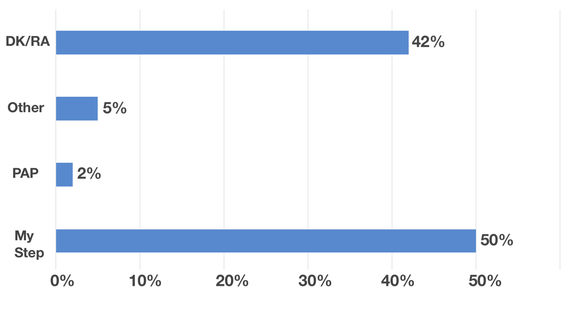

The 2018 ArmES gauged both partisan and non-partisan voters about their political preferences. Not surprisingly, both sets of voters overwhelming preferred My Step PEC. Among voters who identified feeling close to a political party, My Step received a stunning 79 percent of party affiliation. The next closest party was the PAP at a mere 8 percentage points. Among non-partisans, My Step received association from half of the non-partisan respondents. This figure is quite interesting as it points toward the popularity of My Step among the non-partisan public. We can provide two hypotheses as to why a political unengaged individual would choose My Step. First, in the post-Velvet Revolutionary climate it is socially desirable to identify with the My Step PEC. The high marks given to Pashinyan for his job performance suggests an electorate (both partisan and non-partisan) that is overall pleased with the acting prime minister. The second hypothesis suggests that such voters, while still non-partisan, are in the process of forming their political preferences. Since My Step is a relatively new bloc, some voters are still “testing the waters” prior to fully embracing the party. In all, the figures below look quite promising for the future of My Step partisanship.

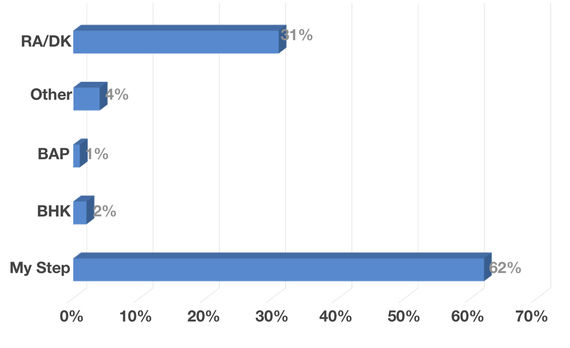

In developing countries, the vote intention question merits a large percent of respondents either refusing or answering “I don’t know.” Such was the case in the 2017 ArmES survey. However, in 2018, when it came to vote intention, respondents overwhelmingly supported the My Step alliance. The bloc received some 62 percent of electoral support. While the ranking distribution is like the actual vote result (First place: My Step; second place: BHK; third place: BAP), the actual vote percentages are lower than the figures reported by the CEC. This is due to the inclusion of voters who answered “I don’t know” or refused to provide an answer.

If we take that figure, 31 percent, and proportionally distribute that amount to each of the three parties, My Step would have 89 percent support of all respondents. In actuality, My Step received about 70 percent of the vote. This suggests that the “undecided” and “non-disclosed” voter went mainly for either BHK and BAP.

The 2018 vote intention results point toward a public that is less “on the fence” about disclosing a vote. The number of individuals who either refused to answer the question or answered “don’t know” was 31 percent, more than half of what it was in 2017. This is quite positive as it suggests that the Armenian voter is forthcoming about their political preferences.

Do You Feel Close to Any Particular Party? (2017)

If April 2017 Parliamentary Elections Were Held Tomorrow, Which Party (alliance) Would You Vote For?

Do You Approve or Disapprove the Way Nikol Pashinyan is Handling His Job as Prime Minister?

Do You Feel Close to Any Political Party? (2018)

Which Party Do you Feel Closest To? (2018)

[For Non-partisans] If You Had to Choose Between The Following Parties, Which Would You Choose?

Who Would You Vote For if The December 2018 Parliamentary Elections Were Held Tomorrow?

What Awaits the Armenian Voter

What are we to make of the 2018 parliamentary election? At minimum, the results of the election provide a new direction for Armenia and the Armenian voter. The era of RPA dominance has come to an end. The central question facing Armenia and the Armenian voter is whether the patronal nature of politics will also cease to exist. Has Armenia left the vicious cycle of patronal politics? Or has a new party of power emerged that will promote a neo-LTP[3] agenda? Supporters of RPA claim the latter. Supporters of My Step claim the former. Let us briefly consider the two trajectories.

If Armenia has abandoned patronal politics and embraced a Western-model of political, economic, and social exchanges then the Armenian voter will gradually develop voter behavior traits that we find in the West. Political parties will no longer be vehicles of patronage and will lack a constant personality-type leader. Instead, political parties will be defined in accordance to their ideological orientation and policy distribution. Parties will increasingly present positions on issues that lack a valence structure. Instead of each party outlining a general platform toward a valence issue, parties will now emphasize positional issues. For example, instead of emphasizing corruption, which is a valence issue and in which every party position is similar, parties will now emphasize taxation or health care, issues where a clear-cut consensus does not exist. At the other side of the political playing field, voters will no longer base their decisions on which patronal network they are loosely affiliated with. Instead, voters will develop specific policy preferences and base their vote calculus on the said preferences. Elections will be the formal process by which government accountability is measured. As V.O. Key said, the voter will become “a rational god of vengeance and reward.”

However, if the new regime continues the vicious cycle of patronal politics then we expect Pashinyan to gradually begin to build a patronal network around him. Transitional justice will become selective justice. Elections will be conducted in an asymmetrical manner where My Step will use state resources to advantage its position. Voters will be coerced to support the party of power. In other words, we will witness much of what we saw during the Ter-Petrosyan, Kocharyan, and Sargsyan eras. In short, is it back to the future?