Crowns worn by monarchs reveal stories of hierarchy and power, providing insight not only to those who wore them, but the strata to which they belonged. Changes in politics and statecraft, shifting contexts, and historical events are all reflected in the design of crowns.

Surviving coins, royal seals, miniature art, and other artifacts provide an understanding into the crowns worn by the monarchs of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (1198-1375). By studying images of the monarchs, it is possible to understand the political context, influences and dominant views of the time.

Byzantine and Western European Crowns

Vardan Hatsuni writes about Cilician Armenian regalia, specifically crowns in his book “History of Ancient Armenia Regalia”. In 1196, the Byzantine Emperor Alexios III sent a crown to the Armenian Prince Levon. However, Levon wanted the “Western” crown, which Hatsuni says was more politically desirable. With these two crowns, “From the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire,” Prince Levon was crowned king in 1198.[1]

To understand the types of crowns worn by Cilician rulers, it is important to briefly examine the evolution of Western European and Byzantine crowns and their types.

During the first three centuries of the Roman Empire, emperors wore diadems instead of crowns. These were simple circlets worn on the head, unlike the ornate crowns of Byzantine kings. The antique royal crown, or diadem, was originally a long white woven fabric that was knotted at the nape of the neck, leaving the ends loose. However, the plain white headband was not grand enough to symbolize power, so they began to embellish it with pearls and other precious stones.

The next type of headdress found in the ancient world was the laurel wreath, which came to replace diadems. In the Roman Empire, crowns made of both laurel leaves and precious metals were used. The traditions of the ancient crown were inherited by the two most powerful powers in the Middle Ages: Byzantium and the Holy Roman Empire, which were themselves formed on the cultural foundation of the Roman Empire.

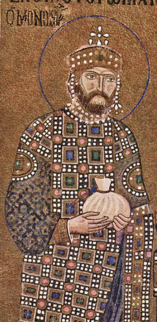

The Byzantine crown underwent two main stages of development. Initially, it started as imperial diadems and eventually evolved into closed crowns called stemmas. The best representation of the headdress prevalent in the early Byzantine period is the 6th century mosaic of Emperor Justinian in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (Fig. 1). The emperor is depicted wearing a bejeweled headdress that flares slightly at the top. The crown is placed directly on the emperor’s head, allowing the hair underneath to be seen. The front of the crown is bejeweled, and strings of pearls (known as prependilia) hang on either side at the temples.[2]

During the 11th century, the headdress of Byzantine emperors underwent gradual changes. The crown became taller, widened at the top, and completely covered the hair.[3] Christianity, being the dominant ideology, influenced both the Byzantine regalia and the crowns. As a result, practically all crowns had a cross on them, situated above the main composition (Fig. 2).

The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire started with Charlemagne, who ruled in the 9th century. The tall crown with a cross on top was first seen on his head. Pictures, coins, and seals from medieval Western Europe show different kinds of crowns.[4]

- Annular shape with radiating stalks that have spherical tips;

- Annular shape with four spheres as rays;

- Rays consisting of three spheres each;

- With lily-shaped rays.

The presence of the cross on crowns was typical in the Byzantine Empire, but it was also used on Western crowns, such as Charlemagne’s. Except for crowns with lily-shaped rays, all other crowns had cruciform equivalents, with the center serving as a pedestal for the cross.

Over time, the Byzantine cross and pearl pendants made their way to the West. Western crowns with spherical rays often featured chains draped on either side, ending in two or three jewels, similar to the Byzantine fashion.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The Byzantine Imperial Ideal

In his article “Byzantium and Armenian Statehood”, Hrach Bartikyan discusses Armenian-Byzantine relations and refers to the issue of the crown.

Speaking mainly about the Bagratuni crown, Bartikyan asserts that Byzantium did not send a regal crown to any Armenian monarch — or ruler of any state for that matter. His approach is based on the Byzantine imperial ideal. According to this ideology, Byzantium recognized only one Basileus (emperor): He who was the emperor of Byzantium. The Divine Emperor was regarded as the master of the entire Oikoumenē (Universe). Since all the other rulers were merely archons (administrators), he was the sole true ruler.[5] The Roman foundation of the doctrine of supreme authority was developed in the pre-Christian era. After the adoption of Christianity, this political theory of the Roman Empire acquired a religious character. The supreme ruler of the Roman Empire was given the title of Anointed-as-Ruler by God’s chosen Roman people.[6]

Bartikyan observes that upon declaring himself king, Ashot Bagratuni was acknowledged by both the Arab Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire. However, while the latter did not send him a crown, they did give him lavish gifts and recognized him as a “prince of princes,” rather than as a king. It is worth noting that the Arabs had already referred to Ashot as “prince of princes” before he became king, but the Byzantines continued to use the same title after he was anointed as king.[7]

According to Bartikyan, King Levon I was the only ruler to whom both the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire Henry VI and the Byzantine Emperor Alexios III, sent a crown. However, as the author notes, the crown was not royal in this case either. “Levon I was internationally recognized as king, and despite receiving a royal crown from the Byzantine court, neither Levon nor his successors were given the title basileus (king), but merely rex.”

According to the 12th century historian Hovhannes Kinnamos, there are numerous imperial and patriarchal letters that have been preserved, addressed to the Armenian kings, in which the Armenian king is referred to as rex, which is a secondary level of king. Kinnamos writes about the difference between basileus and rex, stating that “Latins usually called basileuses emperors — considering them to have supreme power — while secondary rulers were called rex.”[8]

The Cilician Armenian Crown

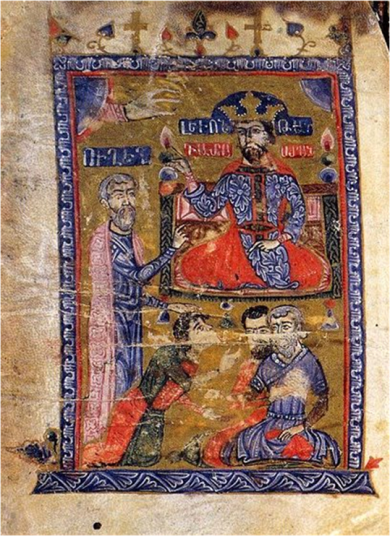

We can get an idea of the crown worn by Levon I from his gold seal (Fig. 4) and coins (Fig. 3). The seal features the first king of Cilicia seated on a throne, wearing royal robes and a crown. This crown has radial spherical ornaments with a cross at its center. The central ray serves as the base for the cross, while pearl pendants hang from either side. The question arises: was this crown granted by Byzantium or the Holy Roman Empire?

We learn about the crown sent by the Byzantines through the accounts of Kirakos Gandzaketsi and Archimandrite Hakob, who describe the crown as cruciform.[9] The only cruciform crown depicted in all the surviving depictions of Cilician kings is the one on King Levon I’s seal. However, it is unclear whether this crown is the same as the Byzantine one.

Before the coronation of Levon I in 1198, and afterward, Byzantine crowns generally had a cruciform shape and pearl prependilia, as mentioned previously. However, the design of the crown on Levon I’s seal differs significantly from all other forms. Byzantine crowns were short and lacked rays, but Levon I’s crown is a perfect replica of Western crowns and duplicates their design. The cross and pearl pendants, or prependilia, had already been used in the Holy Roman Empire prior to Levon I’s coronation.

Figure 3

Figure 5

Figure 4

Figure 6

If we compare Levon’s seal with the seals of German emperors, such as Henry VI and Otto IV (Fig. 5, 6), we can see a clear similarity not only in the composition of the seals but also in the shape of the crowns. As Hatsuni points out, this is not just a material replica of German coins and seals, but is the result of the application of the same crown.[10]

The crowns depicted on Levon’s seal and on the obverse of coins, as well as on other images of the king, are Western-style crowns. While the lion’s crown lacks pearl pendants and a cross, its design is still Western.

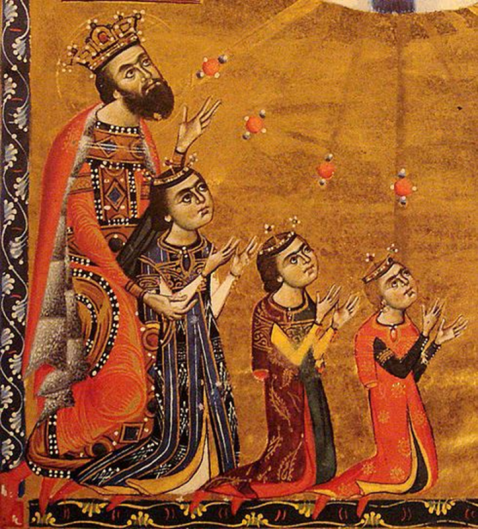

The five miniature portraits of King Levon II (1198 -1219) are also considered an important source for studying the Cilician crown. They are a unique and interesting phenomenon in the history of Armenian and world art. This is because in the 13th century, no ruler of Byzantium or the West was ever depicted more than once or twice.[11]

In the first surviving miniature of Levon II, he is depicted as a crown prince without a headdress [Fig. 7], which is exceptional when compared with surviving images of princes from the previous period.[12] This was primarily due to Western influence. Armenian rulers had never been depicted without headdresses prior to the establishment of the Cilician state — even princes wore them. The two princely Bagratuni brothers, Smbat and Gurgen, are depicted on the bas-relief on the eastern wall of Sanahin’s Church of the Holy Savior. In this image, Smbat is not yet king, but they both wear headdresses. Another image of Smbat and Gurgen can be found on the eastern facade of Haghpat’s Holy Nshan Church. In this bas-relief, Smbat is already a king and wears an Arabic chalma (headdress) sent by the Caliph, while Gurgen probably wears a local crown or helmet-like headdress (Fig. 8).

The royal attire of Cilicia was also influenced by the West. Nerses of Lambron (Nerses Lambronatsi), an influential figure in the Cilician state and Catholicosate, alludes to these relations in his letter to Levon. This letter, also known as the “Letter to Levon”, serves as both a testimonial of Lambronatsi and a response to the complaint written by the abbots of Sanahin and Haghpat. In the complaint, Lambronatsi was accused of being “heretical” and “deviating” from the right path of the Armenian Church by following the practices of the Latins, the Greeks, and others.[13]

In this passage, Lambronatsi not only defends himself but also criticizes Levon. He raises the issue that the king himself has close relations with the Latins and Greeks. Lambronatsi describes various Western customs, including attire, stating, “This is a garment that is shaped like a dress.”[14] Later, when talking about royal attire, he adds “Do not go bare-headed, like the Latin princes and kings, but wear a headdress like your ancestor.”[15] This clearly shows the influence of Western kings and the fact that Armenian kings and princes did not go bare-headed before this time.

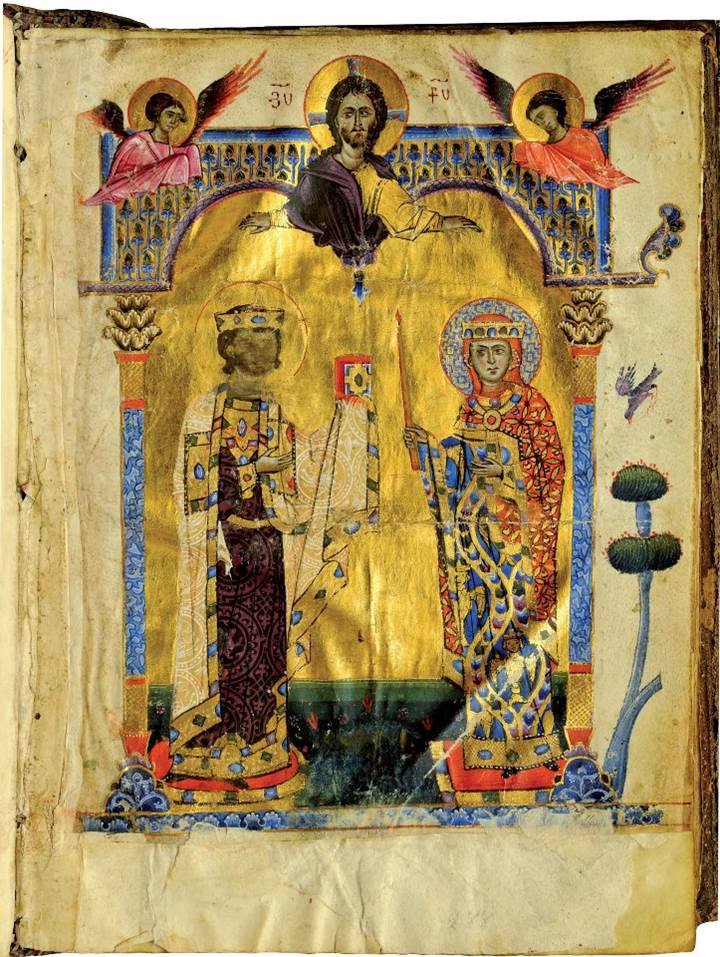

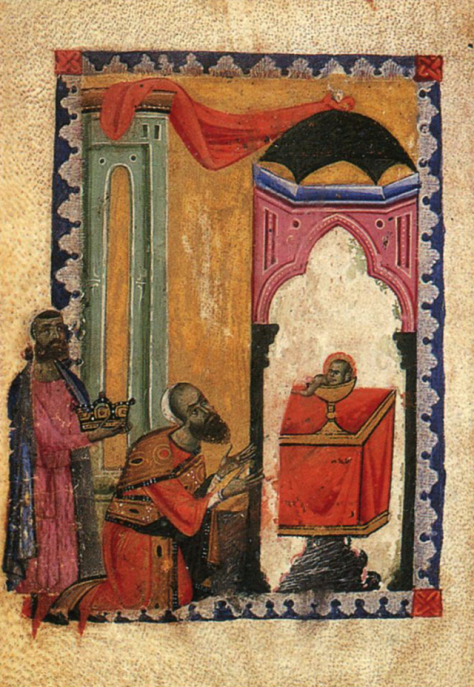

Another image of Prince Levon shows him and Queen Keran in a marriage scene (Fig. 9). They both wear bejeweled crowns, but according to historian Rafael Matevosyan, they are Byzantine crowns.[16] However, this opinion is not accurate for two reasons. First, Levon is still a prince in the image and not a king, so he could not wear a royal crown. Secondly, the crowns on their heads are wedding crowns, not diadems as Matevosyan believed.

The 1272 Gospel miniature of Queen Keran (Fig. 10) depicts the royal family. In this illustration, King Levon wears a crown with spherical rays adorned with precious stones. However, the pearl pendants and cross are missing. The crown is annular in shape and features rays with cones that have orbs on their tip. Unlike other crowns, the rays end with three orbs each instead of one. This same crown appears in his 13th century Prayer Book (Fig. 11). Arakel Patrick detects more independent elements in the crown depicted in Keran’s Gospel, indicating that independent Armenian features are further emphasized in the dress, as well as in the form of the crown, which lacks prependilia decorating the crown.[17] Matevosyan also assumes the crown as being Armenian, but this notion is not substantiated.[18]

However, the absence of prependilia cannot determine the independence of the crown. As previously observed, there are numerous types of crowns without pearl pendants in Byzantine and Western traditions. Both European and Cilician crowns evolved and changed over time. For example, in the Gospel of 1331, King Levon IV is depicted wearing a crown with lily-shaped rays (Fig. 12). This type of crown was popular throughout Europe at that time, as previously mentioned.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Through the depiction of crown shapes in the images that have survived, one can gain insight into the relationships and influences of the time. This includes not only clothing and other material manifestations but also, to some extent, political processes. By studying these processes, we can identify internal conflicts of the time, such as the contradictions among clergymen and rulers.

Studying crowns is important not only as a symbol of power and authority, but also to understand the actual processes that took place during a given period, so that notions about the past are not merely idealized, but grounded in reality.

Studying past events critically, as well as understanding the historical chain of events, is important to impartially judge current realities and draw parallels between the past and the present.

Figure 10

Figure 11

For example, the Byzantine emperors considered themselves as the Divine Emperor and other kings as their brother, son, etc., and did not send a regal crown to the king of any country. This is precisely why we do not see the crown gifted by Byzantium on important Cilician state symbols, such as coins and seals.

Footnotes:

1․ Հացունի Վ., Պատմություն հին հայ տարազին. Վենետիկ, 1923, էջ 232

2․ Ball J. L., Byzantine Dress, New York University, 2001, p. 19

3․ Малеева О. В., Генезис венца как религии власти/ Священное тело короля: Ритуалы и мифология власти, М., 2006, стр. 420

4․ Հացունի Վ., Պատմություն հին հայ տարազին. Վենետիկ, 1923, էջ 235-236

5․ История Византии в трех томах, т. II, М, 1967, стр. 191

6․ Литаврин Г. Г., Этапы эволюции верховной власти и ее репрезентации в Византии VII– XII вв, Репрезентация верховной власти в средневековом обществе (Центральная, Восточная и Юго-Восточная Европа), Тезисы докладов, Москва, 2004, стр. 46

7․ Յուզբաշյան Կ. Ն., Ռոմանոս Լակապենոս կայսեր անհայտ հասցեատերը, Լրաբեր Հասարակական Գիտությունների, № 1, Լենինգրադ, էջ 41

8․ Բարթիկյան Հ., Բուզանդիան և հայ պետականությունը 10-11-րդ դդ, էջ 23

9․ Ալիշան Ղ., Հայապատում, Վենետիկ 1901, էջ 442

10․ Հացունի Վ., Պատմություն հին հայ տարազին, Վենետիկ 1924, էջ 237

11․ Chookaszian L., Once again on the Subject of Prince Levon’s portrait, Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 10 (1998, 1999), p. 32

12․ Chookaszian L., Once again on the Subject of Prince Levon’s portrait, p. 38

13․ Հակոբյան Գր. Ա., Ներսես Լամբրոնացու «Թուղթ առ Լևոն արքայն հայոց» նամակը. Լրաբեր Հասարակական Գիտությունների, № 10, 1970, էջ 73

14․ Հացունի Վ., Պատմություն հին հայ տարազին, Վենետիկ 1924, էջ 232

15․ Ալիշան Ղ., Սիսուան և Լևոն Մեծագործ, Վենետիկ, 1885, էջ 481

16․ Մաթևոսյան Ռ., Բագրատունի թագավորների (Աշոտ I, Սմբատ I, Աշոտ II) բյուզանդական թագը, Հայաստանում քրիստոնեությունը պետական կրոն հռչակելու 1700-ամյակի առթիվ, 2001, էջ 176

17․ Պատրիկ Ա., Հայկական տարազ: Հնագույն ժամանակներից մինչև մեր օրերը, Երևան, 1967, էջ 29

18․ Մաթևոսյան Ռ., Բագրատունի թագավորների (Աշոտ 1-ին, Սմբատ 1-ին, Աշոտ 2-րդ) բյուզանդական թագը, Պատմա-բանասիրական հանդես, Nº 1, 2001, էջ 176