Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Prehistoric vishapakars, or “dragon-stones,” are a prominent example. They represent the institutionalization of water worship, says Arsen Bobokhyan, Deputy Director of IAE’s Department of the Early Archaeology of Armenia and vishapakar specialist. Vishapakars, sometimes simply referred to as “vishaps” (dragons), are native only to the Armenian Highlands. They are four to five-meter long stelae found near water springs—typically 2,000-3,000 meters above sea level․ According to Naira Harutyunyan, they are also closely related to the irrigation activities of the ancient Urartians. The dragon-like images carved on the Bronze-Age[2] statues are tied to folk tales about giant monsters that lived in the mountains in and around Lake Van.

While the most distinctive feature of vishapakars is its round shape, three types exist: bull-shaped (tslakerp), fish-shaped (tsknakerp) and a hybrid of a bull and a fish (tsla-tsknakerp). According to Bobokhyan, there are around 120 vishapakars in different parts of Armenia, the largest concentration of which, 12, is found near Mount Aragats.

Worshipping or attaching great importance to water does not end with vishapakars. Bobokhyan explains that vishapakars belong to a group of cultural representations that have traveled from one period of time to another.

Although different in their design and the locations in which they are found, Bobokhyan considers khachkars to be a transformation of the vishapakar tradition that took place during the Medieval Ages.

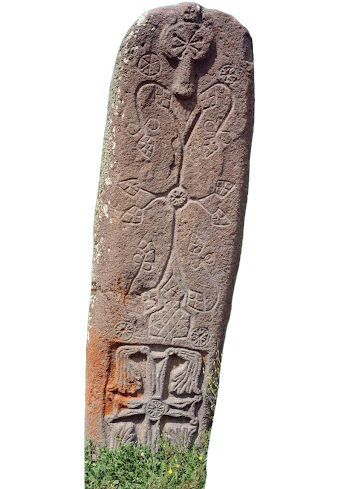

Khachkars (or cross-stones), which are multi-motif cross-bearing monuments, are very well-known representations of Medieval Armenian Christian art that continue to be a part of modern culture for Armenians around the world.[3]

Similar to vishapakars, khachkars also represent a phenomenon that only exists in the Armenian Highlands, a discovery first made by one of the earliest researchers of vishapakars, historian and scholar of the Caucasus, Nicholas Marr. Some of them were even erected next to water sources. Just like the Armenian Apostolic Church adopted the pagan Vardavar holiday into Christianity as the Feast of the Transfiguration, Gasparyan believes it is likely that the Church played a role in modeling khachkars after vishapakars; some are in fact carved directly into them.

Even though their proliferation occurred during the Soviet years, according to Bobokhyan, tsaytaghbyurs have existed since the Middle Ages, with some also resembling dragons like vishapakars. With the atheist ideological pressure of the Soviet Union, it became more common to build tsaytaghbyurs instead of khachkars. Some were erected to celebrate a major event. Others built them as memorials to loved ones that had passed away.

Bobokhyan explains that tsaytaghbyurs exemplify a communal experience. Especially in villages, it is common to set up benches around water fountains. And this goes back to vishapakars and how prehistoric humans similarly created communities around water. For Bobokhyan, the reason for this is simple, as complex as it may seem.