For the Armenian people, the 14th century was marked with loss of statehood (Cilician Armenia), emigration, and the general decline of political, economic and cultural life. The last remaining Armenian noble houses that had still maintained some authority fell off the historical radar. Several of them (voluntarily or by force) converted to Islam and went down the path of assimilation. Others emigrated. Some of them, after losing their secular power, joined the clergy of the Armenian Apostolic Church to preserve the remnants of an Armenian system of governance, and with it their property and privileges.

Despite this, the Armenian people did not give up on their aspirations for unity, as well as liberation and cultural movements. In the 15th century, attempts and plans were made to restore the Armenian Kingdom. It is around these plans that generations, who had not given up on the idea of restoring an Armenian state, would unite and act. One of those plans was the restoration of the Kingdom of Vaspurakan with Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni as king.

Three Paths to the Restoration of the Armenian State

After the loss of statehood in Cilicia (1375), there were at least three paths outlined for the Armenian people to restore their lost statehood in the Armenian Highland: (1) armed rebellion, (2) western intervention, or (3) compromise and dialogue with foreign rulers.

The first path to restoration, that of armed rebellion, was not viable after the fall of the Cilician Armenian Kingdom, especially when emigration was taking place en masse. Members of the Armenian noble houses, which were divided and no longer played an effective role in the political arena, were in no state to carry out armed resistance against the foreign invaders that had made themselves at home. Whatever resistance that took place was more self-defense in nature. Furthermore, the destruction of the Armenian noble houses, which had already begun with the Seljuk-Turk invasion, was well underway by the beginning of the 15th century. The dismemberment of these houses had one purpose: to make the restoration of Armenian political sovereignty or statehood impossible. Finally, as a result of this century-long process, by the beginning of the 15th century, there was no Armenian noble house left that could unite the others. Rushing in to fill the vacuum, Turkic and Kurdish tribes tried to root themselves in their place.

The second path to state restoration, that of western intervention, chased a pipe dream that never materialized but was never abandoned either. The effort continued in the footsteps of Latin preachers (missionaries) until Israel Ori’s[1] campaign and even later. In the 15th century, Armenian houses, such as those of Sasun and Maku, were seeking western support for their claims. In the middle of the 15th century, representatives of the House of Sasun were actively taking part in the formation of an anti-Ottoman alliance, sending envoys (Armenian princes Hetum and Ruben) to Venice to that effect. The Armenian Catholic Prince Nuraddin of Maku also sought western support. This is mentioned by Spanish envoy Ruy González de Clavijo, who was surprised that this Armenian prince, despite being surrounded by Muslims, was able to maintain his rule and remain culturally Armenian.

Those in favor of the third path – that of compromise – were the Orbelians of Syunik and the Sefedinians of Vaspurakan. These two houses played an important role in the 15th century, including moving the Catholicosate from Sis to Etchmiadzin and creating an Armenian principality.

The Two Branches: Syunik-Ayraratian and Vaspurakanian

After the death of Emperor Timur[2] in 1405, the extensive empire he had created was fragmented. Wars for the throne began. The Kara Koyunlu alliance[3], the leader of which was Kara Yusuf, was able to take advantage of the situation. In a short time, he captured Tabriz (1406) and Baghdad (1410), and took control of extensive territory, including a large part of Armenia. As a result of its conquests, however, the Kara Koyunlu state soon clashed with another Turkish alliance in the west, the Aq Koyunlus. The military clashes between these two alliances depopulated many parts of Armenia, some of which was taken over by Kurdish and Turkic nomadic tribes.

Despite this desolate situation, there still remained several Armenian noble houses that were able to maintain a semi-autonomous status, thus playing an important role in the political and cultural life of Armenia. Moreover, some of them had not yet given up on the idea of restoring Armenian statehood. In the 15th century, as was mentioned above, the Orbelians in Syunik and the Sefedinians, who originated from the Artsrunis, continued to embrace such political plans.

The Orbelians were the first ones who took prominent steps toward strengthening political autonomy and restoring statehood, especially when Kara Iskander (r. 1421-1423 and 1431-1436) came to power in the Kara Koyunlu state. Rustam Orbelian had close connections to Kara Iskander. Orbelian was his Grand Vizier and adviser, and also actively took part in military operations. As compensation for his services, Rustam Orbelian received new land in Ayrarat, in addition to his native Syunik, from Kara Iskander, including Aragatsotn, Nig, Kotayk and other provinces. With such privileges, Rustam aspired to create a vassal state. It’s possible Kara Iskander even approved of these aspirations because he tried to repopulate Syunik and Ayrarat with Armenians.

Rustam understood that, besides demographic support, religious support was also vital. This is why steps were taken to move the seat of the Catholicosate of All Armenians from Sis to Etchmiadzin. Without the support of the church, political power could not be consolidated in the Armenian world. Taking advantage of the privileges given to him, Rustam Orbelian donated seven villages under his control to Etchmiadzin in 1431 (the documents presented the donation as a purchase) headed by Grigor Makvetsi [of Maku] (who would later become the second Catholicos in the Catholicosate established in Etchmiadzin in 1441). This was done to secure Etchmiadzin’s economic position by giving it its own income source and preparing it as a center for the nation. The aim was to eventually create an Armenian government on the joint land of Syunik and Ayrarat. However, Rustam Orbelian’s efforts failed. In 1437, Kara Iskander was defeated in the Battle of Sofyan between the Kara Koyunlu and Aq Koyunlu, which was headed by his brother Jahan Shah (1437-1467). Kara Iskander was killed shortly after, and the Orbelian plan was left incomplete.

During this time, the Sefedinians of the Artsruni House of Vaspurakan started to take steps to realize their political and religious plans led by Catholicos Zakaria Akhtamartsi.

Re-establishing the Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin

Jahan Shah’s reign saw relative political stability in the region. During this time, the idea of moving the Catholicosate from Sis to Etchmiadzin was once again being pushed forward within Armenian circles. This was a vital endeavor with political significance and, of course, required much ideological preparation. Indeed, the issue of the seat of the Catholicosate had concerned Armenian secular and religious figures since the end of the 13th century. Initially, the idea was to move the Catholicosate from Sis to Gandzasar (in modern-day Artsakh). This idea was supported by Hovhan Vorotnetsi (1315-1386). However, support to move the seat to Etchmiadzin was greater. Some of these prominent supporters were Grigor Tatevatsi (1346-1409) and his students (Tovma Metzopetsi and Hovhannes Hermonetsi). Etchmiadzin’s appeal derived from its history as the original seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church, and chosen by Gregory the Illuminator. It also had the support of the political elite as evidenced by Rustam Orbelian’s concession of seven villages in 1431.

Hence, the representatives of the Vaspurakan and Syunik branches were the main players in the plan to move the Catholicosate to Etchmiadzin, led by Tovma Metzopetsi (1378-1446) and Hovhannes Hermonetsi. Metzopetsi viewed the establishment of the Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin not only as a religious, but as a political move as well. This is why he was against acts of rebellion, as well as Georgian support. Metzopetsi was one of the prominent supporters of restoring Armenian statehood through compromise, a path favored by the Vaspurakan branch.

During this time, the Sis Catholicosate had lost its role as the “Catholicosate of All Armenians.” It was quite discredited, especially due to the buying and selling of positions within the church and many other similar incidents. At the end, the Sis Catholicosate took its final blow in 1439, when Grigor IX Musabekiants was appointed Catholicos of Sis through deceptions and bribes. Musabekiants was not able to extract the support of the popular dioceses of Tatev, Haghpat, Bjni and Artaz. The strongest claim to moving the Catholicosate to Etchmiadzin came when, due to uncertain circumstances, the Right Hand of Gregory the Illuminator had “by chance” ended up in the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin. Much importance was given to this religious relic “as a stamp and guarantee of a lawful and true patriarchate” (M. Ormanyan).

Thus, in 1441, with the active participation of the Syunik-Ayrarat branch, the Armenian See was re-established in Etchmiadzin. A national church council was called with the consent of Kara Koyunlu leader Jahan Shah, his son Hasan Ali, and the ruler of Yerevan Yaghub Bek. Indeed, the support of Jahan Shah and the others for establishing the Armenain Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin had its economic and political reasons. Catholicos of Akhtamar Zakaria III Akhtamartsi and Catholicos of Gandzasar Hovhannes Hasan-Jalalyan had sent their written consent to the council in advance. At the same time, Catholicos of All Armenians Grigor IX Musabekiants was also invited to the council so he could be re-annointed as Catholicos of All Armenians with its new seat already in Etchmiadzin. The latter rejected taking part in the council. However, he also didn’t try to stop it from taking place. Zakaria Akhtamartsi was the only candidate for Catholicos who was from native Armenia and had the title of Catholicos. He was the Catholicos of Akhtamar and hoped that, through this logic, the seat of the Catholicosate, now moved to Etchmiadzin, would be entrusted to him. However, this did not happen. Representatives from Ayrarat and Syunik had their own candidate for Catholicos and were against one from Vaspurakan, despite the fact that they were unanimous in establishing the Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin.

Indeed, it would have been reasonable for Zakaria III Akhtamartsi to become the Catholicos; it would have allowed the Vaspurakan and Syunik-Ayrarat branches to finally overcome the hostility and estrangement between them, and unite the Catholicosates. However, as Ormanyan has accurately observed, “provincialism” won out. Zakaria’s candidacy was rejected. However, they were able to come to a certain agreement. A candidate acceptable for both sides was appointed Catholicos: Kirakos I Virapetsi (1441-1443). Eventually, the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin was established without any opposition, since both the Sis and Akhtamar Catholicosates were not against the candidacy of Kirakos I Virapetsi.

Ultimately, the Vaspurakan branch came out victorious because Kirakos Virapetsi was originally from Vaspurakan (from Kajberunik). This was something that the Syunik-Ayrarat branch could not tolerate for long; it was they who initiated the establishment of the Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin, and it was they who also played an important role in the Eastern Armenian reality. That is why they were able to convince and bribe Yaghub Bek to oust Virapetsi as Catholicos in 1443 and appoint Grigor X Makvetsi (Jalalbekiants, 1443-1466) in his stead. This was also made possible due to the 1431 land certificate mentioned above, according to which the seven villages were donated to the monastery of Etchmiadzin but with the condition that he had to remain abbot of Etchmiadzin until his death. This was also why Grigor Makvetsi was always co-Catholicos with all four Catholicoi that succeeded him.

Several years later in 1446, taking advantage of this chaotic situation, Archbishop Karapet Evdokatsi created the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia in Sis. Once again, the possibility of church unity was squandered.

However, Kirakos Makvetsi managed to dissolve the Akhtamar Catholicosate, which had been established in the Black Mountain Council of 1114.

Zakaria III Akhtamartsi: Catholicos of All Armenians

The dissolution of the Akhtamar Catholicosate was already an important move for Zakaria Akhtamartsi and allowed him to actively conduct his work. Zakaria had decided to unite the Akhtamar and Etchmiadzin Catholicosates and have himself seated as the head of the See of All Armenians: the Mother See of Etchmiadzin. Afterward, his plan was to start working toward political unification. Not coincidentally, around this time, the fact that Zakaria Akhtamartsi came from a “lineage of royalty” started to spread. This, of course, had historic foundations: the Sefedinians, in fact, did originate from the Artsrunis, the “family of King Gagik,” and had been able to maintain their royal powers as meliks in Vaspurakan.

Zakaria Akhtamartsi was also taking steps toward political unification. He had already showcased himself not only as a cleric, but also as a flexible diplomat and skillful military man. He had his own military detachment and had used force when necessary. In 1459, Seid Ali, a representative of the Kurdish Rojik (Roshkanits) tribe, took advantage of the chaotic situation in the country and tried to invade and plunder Akhtamar Island with two boats. When Zakaria Akhtamartsi found out about it, he attacked first, capturing the boats and forcing the Kurdish bandits to flee. After this incident, Zakaria Akhtamartsi’s reputation grew sharply. It seemed as if the tensions surrounding the Catholicosate in Etchmiadzin were nearing their end.

In the same year of 1459, an opportune occasion arose. When Zakaria Akhtamartsi heard news that Jahan Shah was victoriously returning from his conquests, he went to greet him with many gifts. The meeting took place in the city of Tabriz. It was at this meeting that Zakaria received the right to hold the seat of Catholicos of Etchmiadzin from Jahan Shah. Thereby in 1460, Zakaria Akhtamartsi took the Catholicosate. The joining of the Akhtamar and Etchmiadzin Catholicosates was an important step for the stateless Armenian people because it created an opportunity to establish the right of a uniform system.

After being anointed Catholicos of All Armenians, Zakaria Akhtamartsi made sure to strengthen and broaden the political rights of the Sefedinians. In 1461, Zakaria III Akhtamartsi was able to reconcile Jahan Shah and the Emir Sharaf of Baghesh. (Military clashes were expected since the latter had refused to pay taxes to the central authorities, and these clashes would have made the Armenian people of the region suffer greatly.) After this, his political weight only rose. However, the situation soon changed drastically. In 1461, Jahan Shah’s son, the ruler of Shiraz Pir Budagh, rebelled against his father. To stop the rebellion, Jahan Shah organized a campaign toward the east. The enemies of Catholicos Zakaria took advantage of this situation. With the help of Jahan Shah’s other son Hasan Ali, they tried to oust Zakaria. When he found out about these plans, Zakaria Akhtamartsi went to Akhtamar, taking with him the Right Hand of Gregory the Illuminator (and other holy relics).

However, before fleeing to Akhtamar, Zakaria had already started working toward the restoration of the Artsruniats Kingdom (probably with the aim to restore the Armenian Kingdom) once he took control of the Catholicosate. One of the most important steps he took in this regard was in 1461, when Zakaria Akhtamartsi commissioned a book of rituals called “Archbishop Mashtots and the Ordination of the Catholicos and the Crowning of the King”.[4] The part on “Crowning of the King” already shows that Zakaria Akhtamartsi planned to use this “Mashtots” to crown his nephew Smbat. This plan, however, remained incomplete. At the end of 1464, Zakaria Akhtamartsi was murdered by poisoning in a conspiracy.

Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni: The Last Crowned Armenian King

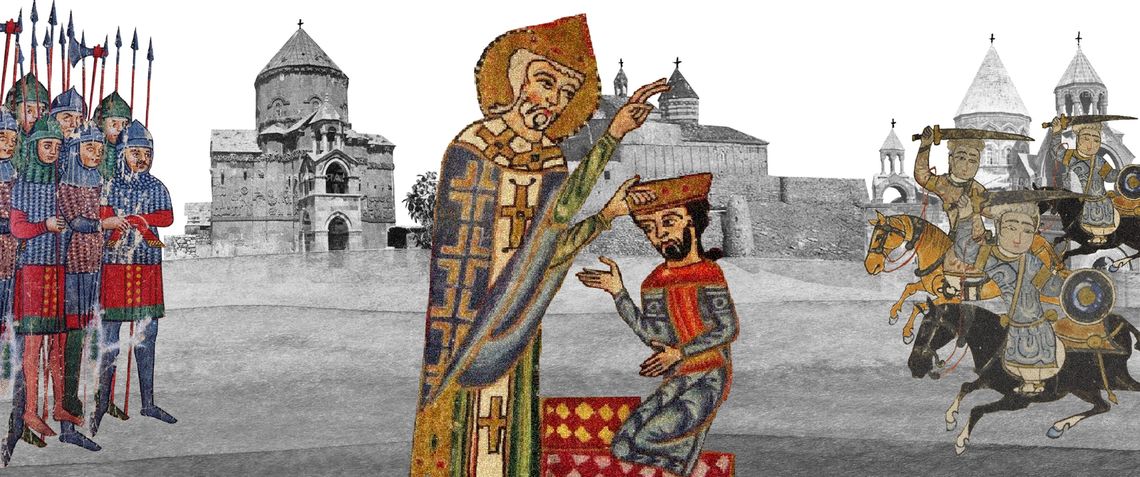

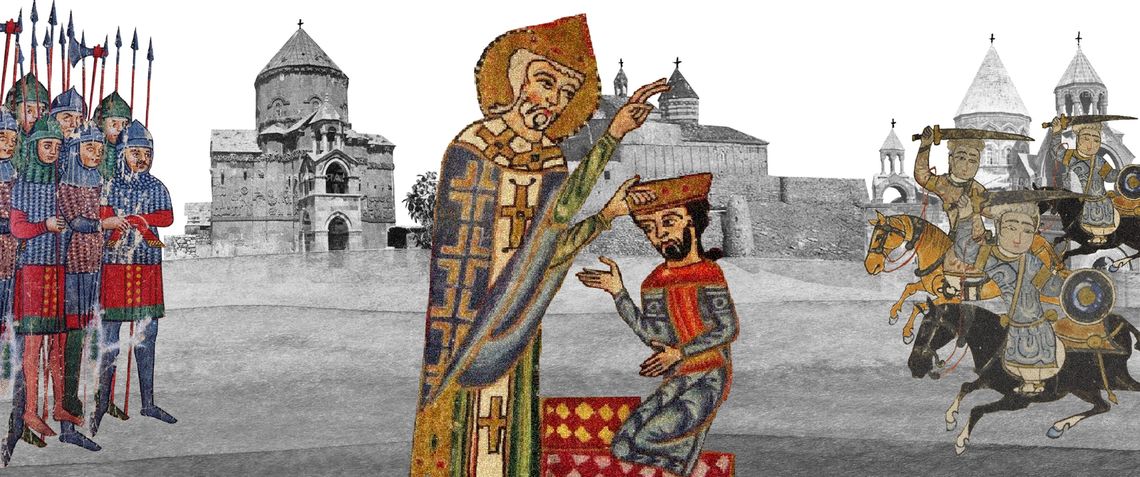

What Zakaria Akhtamartsi could not achieve in his lifetime was successfully achieved by his nephew Stepanos IV Tgha (the Boy) (1465-1489). He also enjoyed the patronage of Jahan Shah and was able to become Catholicos for a short period of time. In 1465, with the blessing of Jahan Shah, Stepanos’ brother, Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni, was crowned king. A memoir from the time of these events writes, “And then they crowned Master Smbat as king like his forefather Gagik, because the Armenian nation had been deprived of a king for a long time.” Indeed, this had no legal-political significance. However, it was culturally important in terms of restoring the ritual of crowning a king.

The details of this noteworthy event can only be found in a 1471 copy of a manuscript,[5] in which the crowning of Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni is also illustrated. In the illustration, Catholicos Stepanos IV Tgha is crowning a kneeling Smbat.

Indeed, Jahan Shah’s blessing did not come from his love for the Armenians, even though the Armenian side accepted this fact with great enthusiasm. It is my opinion that Jahan Shah wanted to hand over the Van governorship to the Sefedinian-Artsrunis, through which he would be able to resolve several issues. First, by doing so, he would challenge the Kurdish tribes, especially since that land was, until that point, under the jurisdiction of the amiras of the Kurdish Shamboyan tribe. Representatives of this tribe also originated from the Artsruniats Armenian royal house’s Senekerimian family from their maternal side. Second, by promoting the position of the Vaspurakan branch, Jahan Shah was also creating a certain counterweight to the Syunik-Ayrarat branch, thus making control over the Armenians easier. On the other hand, however, Jahan Shah’s move went even further: by creating an Armenian “kingdom,” he was also going againsts Uzun Hasan from the Aq Koyunlu, who enjoyed the support of the Armenians under his jurisdiction.

In any case, Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni’s reign did not last long due to the drastic geopolitical changes that soon took place. At that time, clashes had ripened within the Kara Koyunlu and Aq Koyunlu tribal alliance. After suppressing Pir Budagh’s rebellion, Jahan Shah prepared for his final battle with the Aq Koyunlu’s Uzun Hasan. That battle took place in 1467 and ended with the defeat and murder of Jahan Shah. Afterwards, the Kara Koyunlu alliance quickly fell apart and was replaced by the Aq Koyunlu. The following year, the latter established their reign across all of Armenia. It is this year, 1468, that we can probably state to be the end of Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni’s reign. He had enjoyed the patronage of Jahan Shah and could not earn the trust of Uzun Hasan. This was the fate of the Vaspurakan experience of trying to restore Armenian rule and this was the end that the last crowned Armenian king, Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni, met. The last time he is mentioned in any historic document is in 1471.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can state that aspirations to restore statehood were not possible without acknowledgement of territories (Vaspurakan, Syunik, etc.). Instead of considering the restoration of self-rule important, its geographical place was valued more. It is worth noting that, in the 15th century, the Vaspurakanian and Syunik-Ayraratian branches did collaborate once in a while, but were mainly in conflict with each other. The aim of the former (Vaspurakanian), in my opinion, was the establishment of church unity (through uniting the Catholicosates) and the restoration of self-rule (statehood). Meanwhile, the establishment of church sovereignty and handing the church some state functions was what was important for the Syunik-Ayraratian branch. In the end, the Vaspurakanian branch lost.

Despite all of this, the Vaspurakantsis did not lose hope in restoring sovereignty. There is a notable testimony from the 1620s from a Carmelite missionary R. P. Philippe de la Très Sainte Trinité, who had visited Vaspurakan. In his travel notes, he writes, “The Great Senor (Ottoman Sultan) and the Persian king have divided Armenia even though they have a secret king (de Roy secret) who originally comes from the oldest Armenian kings whom the patriarch crowns secretly, as he told our fathers [and] very few people know about it.” In the Armenian reality, the presence of this “secret king” is probably a recollection of the crowning of Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni as king in Vaspurakan in 1465. This kept the hope of restoration of statehood alive. As impossible as it was to realize the Vaspurakanian branch’s aspiration of joining the Catholicosate with the royal throne, it, in any case, was an important precedent.

—————————————