The perception of the urban space of Paris will hardly change if there is a house added or a house removed because of gentrification, new architectural influences or a calamity. A city changes with the rhythm of modern life and in parallel to new cultural, political and economic demands. Paris changes, as do all modern day small and large cities, but the character of the city still remains in the writings of Hugo or Balzac. The city, as Roland Barthes puts it, exists as a place to be read and is therefore unique in every individual reading, it is also a place to be written. Some texts about cities have replaced the physical density of streets and houses to such an extent that any attempt to read the urban space seems impossible without referencing, without viewing it through the prism of works written about the city. There is no need to even pick up travel guides, which in recent decades have aspired to also double as sources covering the historical, spatial and cultural realities of any city. It is obvious that a new direction of global literature is being formed, which can tentatively be called urban literature or urban fiction. It is not only well known cities that through a concentration of literary texts have received a new portrayal like London or Venice did thanks to the works of postmodernist writer Peter Ackroyd, or Lisbon thanks to Fernando Pessoa, but also unexpected places from Naples (Elena Ferrante) to Barcelona (Carlos Luiz Zafon), Santa Teresa (Roberto Bolaño), Aix-en-Provence (Peter Mayle). The new urban fiction is developing in the most unusual ways and reaching the most diverse layers of the urban microcosm.

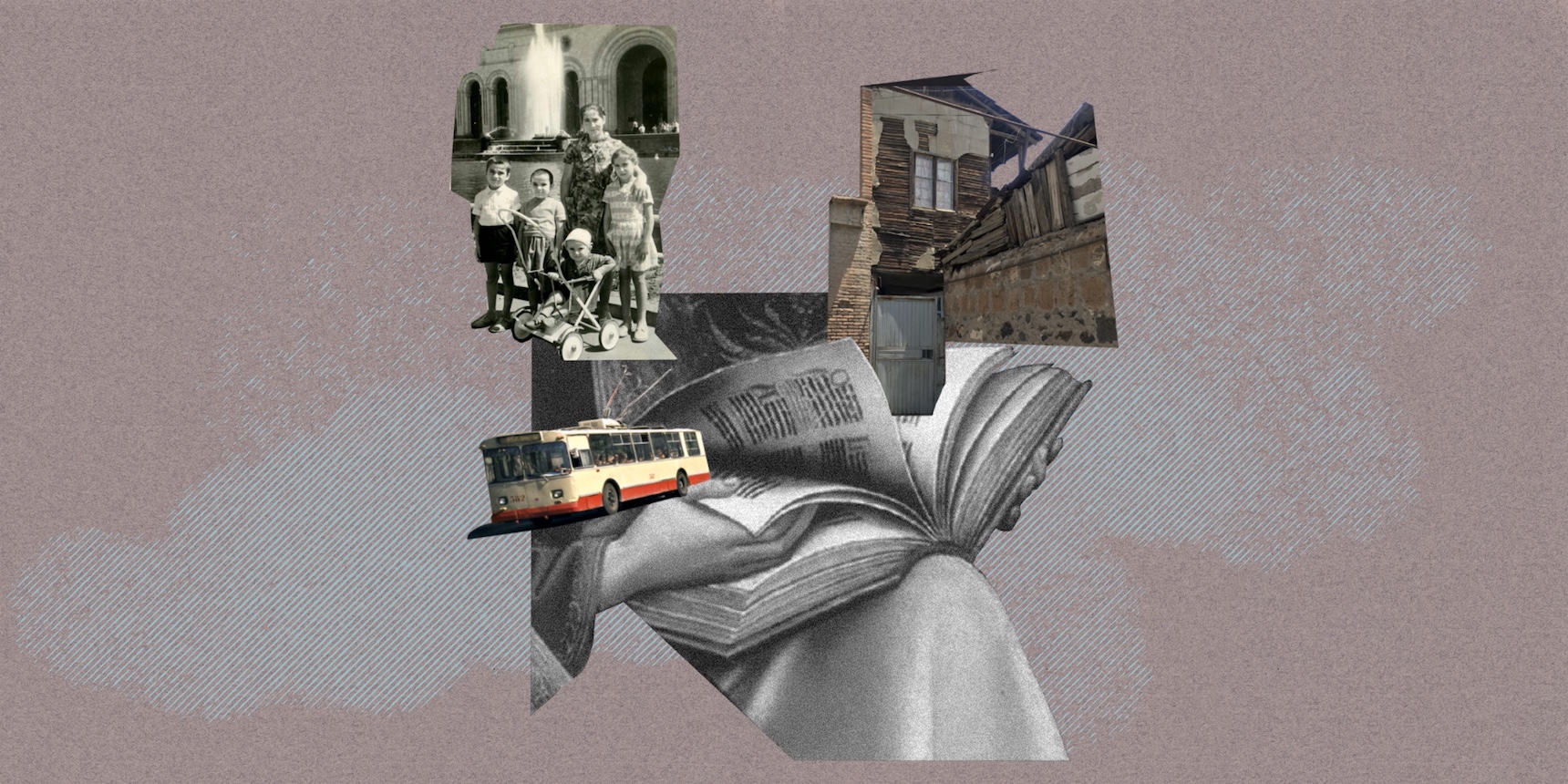

In the last century, Armenian literature and Armenian non-literary/fiction writing/text, created the “Sunny City ” of Yerevan, which became the lens that mediates the truth when reading the city. Sunny Yerevan, sunny Tbilisi, sunny Alma-Ata and a list of other sunny cities seemed to be a code for a colonial reading of space, in a context where the southern cities were doomed to be nothing more than a sunny paradise for the cold capitals of the north. The Yerevan, glorified in the literature of the 20th century, is a Soviet project, Tamanyan’s idea, that literature has hinted at and has responded to. Some authors still continue the mythification of Soviet Yerevan, despite the fact that Armenian literature has long detached itself from Soviet and sometimes even post-Soviet writing. Some writers still see the city through the prism of their feelings and memories, experiencing nostalgia for the sunny Yerevan in their autobiographical works.

In contrast, the new literature makes the city the subject of re-reading, trying to re-see both the literary archive and our reality by changing the lenses and re-positioning. Aram Pachyan’s prose is a completely new way of re-reading the urban literary past. Urban researchers and anthropologists (see multidisciplinary projects about Firdus, Kond and other spaces), desperate with the endless gentrification, have also fixated their gaze at the city floating away by the hour, trying to register, understand and analyze it. Pachyan, through his prose, has succeeded in simultaneously rendering several directions that pertain to contemporary Armenian literature. In a way, Pachyan’s writing is its unique form of urban anthropology, compiling on the pages of his novel «P/F» fragments of events, things, tales, urban legends and gossip. On the other hand, Pachyan is creating a book of memory and avoids the “nostalgia” for the Soviet city unlike the acclaimed children of acclaimed writers, while still working with such a complicated phenomenon as is the memory of a place, the place that has shaped the identity of ordinary people. Contemporary Armenian literature has noticeably made several important turns — anthropological, anti-colonial, feministic, etc… and Pachyan’s memory book should be viewed precisely in the context of this shifting literary discourse.

Pachyan’s city lends itself to the reader from different perspectives of memory, as if decentralizing the discourse on space. It materializes through personal memories, archival documents … and most interestingly, cultural memory that compliments the narratives of the past. Pachyan shows the city through the perspective of a different kind of a writer, literally forcing us to read “another” Yerevan. As such, it is difficult not to take notice of the other role Pachyan plays in this contemporary cultural space — that of the archivist. He digs into the deepest basements of libraries to revive the names of long forgotten or lesser known authors, authors contemporary literature has severed from us for being the “past,” the “Soviet past”… Thanks to Pachyan, one of the names that returned to the literary scene is Mkrtich Armen with his “Yerevan”, “Zoubaida” and other works that document that which was left outside the margins of literature glorifying Tamanyan’s project. Armen’s prose, in parallel to the rise of the Soviet city shows a Yerevan woven with crooked old streets, makes the sound of the river audible, which Soviet and post-Soviet authorities had pushed out of the urban landscapes manifested by ordinary people. However, that was the city Mkrtich Armen had chosen as his subject for urban fiction and it is Armen’s “Yerevan” that becomes one of the integral parts of the cultural memory that Pachyan returns to the contemporary reader through the pages of his prose.

The city and the urban space are constantly present both in modern poetry and prose (Armen Shekoyan, Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan, Hovhannes Tekgyozyan and others write about Yerevan), Yerevan is also the place and the moving force behind hybrid works and graphic stories, like Artavazd Yeghiazaryan’s “The Secret of the Dragon Stone” and “Armenia” by Armen Hayasdantsi and Harutyun Tumaghyan (Har Toum). However, we can’t unequivocally say that contemporary Armenian literature has created a strong narrative of the city, which would be the unique key in reading Yerevan or other Armenian cities. Arguably, writing the code to read Yerevan might not be a matter of principle for contemporary literature, that is with the exception of literature written for mass consumption and memoirs that continue to be reproduced, unaware that the times have changed and so has the urban milieu, fundamentally. For contemporary prose, denying the grandfathered code of reading urban character, is the more interesting process. Pachyan best accomplished this deconstruction of urban text, with caution and sensitivity, by approaching the space not directly but through the mediation of the “other” writing about the city. Contemporary Armenian literature has not dedicated a novel to Yerevan as Axel Bakunts once did to Goris. Contemporary Armenian literature, in its role as a researcher/explorer, turned toward the literary past, toward collective memory and merely showed us the novel that was already written. Yerevan had her novel, it was simply forgotten, removed from our memory. Contemporary prose shed light on the darkness of oblivion and helped us remember “Yerevan”.

Magazine Issue N27

Books & Literature

The magazine issue for March — “Books and Literature” — include articles about the art of translation, what it means to be a literary agent in modern day Armenia, memory and literature, how books can help teach children about disabilities, and how Armenian literature created the image of Yerevan as a “sunny city” during the last century, serving as a lens to read the capital of the country.