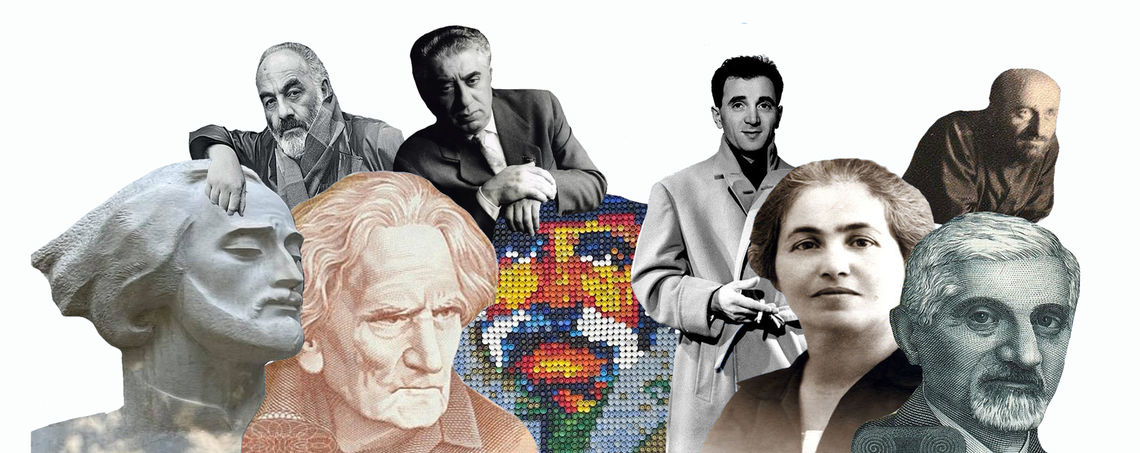

Aram the son of a bookbinder from Tbilisi; Soghomon, the orphaned son of a shoemaker; Martiros from Doni Rostov. Then there is Alexander standing under the house of Shahnour Vaghinag, that musician from Paris, and the one from Fresno who wrote “My Name is Aram,” except it wasn’t, it was William.

While there is much to be said about whether statues, gigantic replicas of the acclaimed, are a cultural necessity, a tribute or ornamental peacocking of value by association, there is, however, a statement of sorts in the claim set forth by the over-monumentalizing of an organic part of one’s own. Between the Opera and Cascade, in the space of a few city blocks, a coincidental covert message emerges: The concentration of statues and who these statues are of delivers a reassurance that those unborn, unfed and uncultured in the ways of the local, are of essence to the more panoramic understanding of Armenia and more so to the anchoring of what is recognized as Armenian.

Far be it from any of us repatriates to compare our contribution to those of the greats; hopefully some of us will one day be deemed worthy and those unworthy will not proclaim neglect, but there is a clear thread, a link between them and us. A reminder that Armenianness only in the context of Armenia is an Armenianness without Komitas or Khachatryan. It is a Yerevan without Alexander Tamanyan, it is a stage without its most sensual chansonnier, without an Aznavour.

Armenianness without Western Armenian is an Armenia without its first Declaration of Independence. It is Tumanyan writing in classical spelling but only being read in Eastern Armenian. With Western Armenian, you can walk down Abovyan Street, where Zabel Yesayan briefly lived, imagine overhearing a conversation disrupted in that most special way when both speak the same language yet don’t.

“You don’t sound local, where are you from?”

“It is difficult to explain…Istanbul but then France and then Bulgaria, but I’m Armenian.”

“Your Armenian is not so good,” says the lady behind the counter at the store once in Eastern Armenian and once again in Russian, hoping if Zabel is Armenian then she should surely understand Russian and without waiting for an answer because that was a statement and not a question, she continues, “The bukhanka is fresh,” and hands her one.

“Who leaves Paris! Capitalism must be dying, why else would you be here?”

“Where else would I be?”

Repatriation

Magazine Issue N10

Tamanyan moved to Armenia twice. The First Republic was short-lived and the newly Sovietized Armenia was a dangerous place. Tamanyan left and then Tamanyan returned to build his garden city. We have since kept the city and ditched the garden.

Saroyan first visited Armenia in 1935, on a trip paid for with some of his first earnings as a writer – and as the New York Times writes – at the precipice of becoming a literary household name. ”I wanted to see the country, the place of my father and my ancestors, and to breathe the air which all of us had breathed for centuries,” he wrote, giving himself away as the typical overzealous tourist one might see in Vernissage looking for a painting of Mount Ararat to take back home. His parents were from Bitlis, the Ottoman Empire, a geopolitically, culturally, historically, linguistically different place from Soviet Armenia, yet Armenia was a legitimate alternative. He came again in 1978.

In 1939, Aram Khachatryan came to Armenia for a six month study trip, for a deeper study of Armenian folk music which had inspired and would continue to inspire his compositions. About a decade later he would again come to Armenia but this time it was “exile.” He had displeased Moscow, his music was too “formalistic,” too inaccessible to the people. Moscow decided what better way to punish the superstar composer than to send him to Armenia, a place he was culturally attached to but a place that was not domestic to him. Khatchatryan apologized to Moscow for the wrong he did not know he committed and was thankful to be allowed back that same year.

Repatriation is a heavy word. Repatriation in the Armenian context is even heavier given how the Soviet propaganda machine welcomed and then forwarded thousands of repatriates into ditches in Tiga. Repatriation is also often the wrong word. For the Armenian diaspora it is rarely a return to the place of origin or country of citizenship. Armenia is not the origin of the classical diaspora, Armenianness is. Citizenship is not our civic right but granted to us on the grounds of Armenianness. Citizenship is also a great equalizer. What is left after your rights and responsibilities to Armenia are instated by citizenship is a spectrum of cultural influences that has enriched Armenia more than we often care to recognize.

If we step away from the harshness of our self-imposed narrative – when someone leaves Armenia they have tragically immigrated, if someone moves to Armenia they have selflessly repatriated – we might just see what those amplified replicas of all who passed through here before us are evidence of. Armenia is many things to many people. An emotional surrogate for a lost homeland, a legitimate alternative, a place of opportunity or refuge, an old new place with a gravitational force that pulls you in, yet can repel you.

Armenia is multicultural in the most covert ways, a landlocked country who has an Ayvazovsky. Whether you are moving forward by moving back or moving away, you are in its orbit.

Armenia was exile for Sayat Nova, a place where Komitas came looking for peace and found contention, it was punishment for Khachatryan, an emotional placeholder for Saroyan to visit and for Yesayan, an ideological destination. Parajanov considered moving to Armenia because a house and a museum was promised and hopefully an end to persecution. For Tamanyan, it was a place to build.

So, if you are here for your six month study trip, then be it. If you are here to breathe the air and marvel at the Mountain then be it. If you are here to build, then build. If you are here because you have nowhere else to go, then be here. If this is your transit, then pass with ease. If you are just living here for now then it does not matter if you are singing Pour Toi Arménie or if this is your La Boheme.