Biography of the President

Levon Ter-Petrosyan (often abbreviated “LTP”) was born in Aleppo, Syria, to parents from Musa Ler, known for their resistance against the Turks during the genocide. For generations, his paternal ancestors served as priests in Cilicia, hence the “Ter” prefix on his last name. His father, Hakob, was a member of the left-wing Hunchakian party, and then a founding member of the Syrian-Lebanese Communist Party, who volunteered to fight for the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. The Ter-Petrosyans, along with tens of thousands of other diasporans, repatriated to Soviet Armenia in 1946, a year after Levon was born.

The son of genocide survivors, Ter-Petrosyan grew up in Yerevan. He majored in oriental studies at Yerevan State University and completed his postgraduate studies at the Leningrad branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Returning to Armenia, Ter-Petrosyan began his career at the Abeghian Institute of Literature as a researcher. In 1978, he began working at the Matenadaran, the museum-institute of Armenian manuscripts. In the 1980s, he taught at the Gevorgian Seminary in Etchmiadzin. In 1987, he defended his doctoral dissertation on Armenian-Assyrian literary ties in antiquity. Ter-Petrosyan is fluent in Armenian and Russian and has a working knowledge of French, English, German, Arabic, Assyrian, Aramaic, Ancient Greek, Latin and Biblical Hebrew.

Ter-Petrosyan’s engagement in politics began during his university years. In 1965, when the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide was first publicly commemorated, he took part in demonstrations advocating for the Armenian Cause. In the fall of 1987, he organized a petition among Matenadaran employees calling for the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Soviet Armenia. Beginning in February 1988, when massive demonstrations swept Yerevan with the same demand, he gradually became a leading spokesperson for the cause. On December 10, 1988, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev visited Armenia to inspect the aftermath of the December 7 earthquake, Ter-Petrosyan and other leaders of what had become known as the “Karabakh Committee” were arrested. They were released on May 30, 1989.

Rise to Power

Ter-Petrosyan’s rise to power occurred in the aftermath of the parliamentary election in 1990, held in two rounds on May 20 and June 3. Pro-independence candidates formed the Armenian National Movement (Hayots Hamazgayin Sharzhum) faction within the Supreme Soviet, or Supreme Council (Geraguyn Khorhurd), as the parliament was then called. After several close rounds of voting for Chairman with Communist leader Vladimir Movsisyan, Ter-Petrosyan eventually came out on top on August 4, 1990. Under his leadership, the Supreme Council adopted a Declaration of Independence on August 23, 1990, which proclaimed the country’s desire to begin its path toward sovereignty. It officially renamed the country to the Republic of Armenia.

In March 1991, Armenia rejected the proposal of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for a new union. Armenia’s de jure independence came when an independence referendum was held on September 21, 1991, and the independence of the Republic was officially declared by the parliament two days later.

Ter-Petrosyan was popularly elected President on October 16, 1991, with 83% of the vote, crushing Paruyr Hayrikyan, a prominent Soviet-era dissident, and Sos Sargsyan, a beloved actor nominated by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, or Dashnaktsutyun). Ter-Petrosyan was inaugurated as independent Armenia’s first president on November 11.

Major Challenges

Ter-Petrosyan was elected Armenia’s first president at a time when the country faced major socio-economic and security challenges. Due to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Armenia was blockaded by Azerbaijan and later Turkey, while Georgia was in turmoil due to a civil war and conflicts in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Armenia did not initially have a secure land link with Iran. With the Soviet disintegration, Armenia’s economy collapsed dramatically. Factories gradually closed, unemployment skyrocketed and skilled workers emigrated.

Armenia’s northwestern part, what is now Shirak and Lori regions, were still devastated by the December 1988 earthquake, with many living in temporary housing, while around 300,000 Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan had settled in the country. Based on a poll conducted in November and December of 1993, after the introduction of the dram, the national currency, it was estimated that 80% of Armenia’s urban residents could not purchase basic foodstuffs. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reported in 1996 that only 4% of Armenians could meet their family’s daily needs.

High-Profile Murders

Perhaps the most high-profile murder during the Ter-Petrosyan presidency was that of Marius Yuzbashyan, the head of Soviet Armenia’s State Security Committee, better known by its Russian initials KGB, from 1978 to 1988. He was shot dead on July 21, 1993. The murder remains unsolved to this day.

After Ter-Petrosyan was ousted in 1998, numerous charges were brought against a close ally of his, Vano Siradeghyan, the notorious Interior Minister, whose whereabouts have remained unclear since he fled Armenia in 2000. Siradeghyan was notably charged with ordering the assassination of Hambardzum Ghandilyan, head of Armenian Railways for two decades, on May 3, 1993.

The last prominent assassination during Ter-Petrosyan’s presidency was that of Hambardzum Galstyan, mayor of Yerevan in 1990-1992. Galstyan was also an early member of the Karabakh Committee, but later became a critic of Ter-Petrosyan. He was gunned down on December 19, 1994.

Trial of the ARF

Ter-Petrosyan had an uneasy relationship with the ARF from the start, but it became particularly evident after the war in Artsakh ended and international divisions in Armenian politics were exacerbated. In July 1992, he ordered the expulsion of Hrayr Maroukhian, the ARF Bureau Chairman, who was a Greek national. Ter-Petrosyan grew increasingly authoritarian in the post-war period. Their relationship reached a low-point on December 28, 1994, when Ter-Petrosyan, in a televised speech, accused the ARF of having harbored DRO, a secret organization he claimed was engaged in assassinations, drug trafficking, terrorism and espionage, and “was planning to destabilize the country by committing more murders.” Ter-Petrosyan effectively suspended the party. Upon a request from the Justice Ministry, the Supreme Court formally banned the party for six months on January 13, 1995, citing violations of the law on political parties. Thus, the ARF, a key opposition party, could not run in the parliamentary election in early July 1995. Apart from the party itself, ARF-affiliated organizations including newspapers were also shut down. 22 ARF members were arrested, one of whom, Artavazd Manukyan, died in custody. The Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, a US government agency monitoring human rights, noted that “defendants’ access to attorneys has been restricted, and the lawyers themselves have reported harassment, intimidation and beatings.” Freedom House noted that the trial was “marked by several serious inconsistencies and persistent violations of the defendants’ rights to due process.” In May 1995, Ter-Petrosyan explicitly blamed the ARF for the murders of four individuals, most notably Hambardzum Galstyan, and called the ARF a terrorist organization. Eventually, all defendants were found guilty, but according to Stephan H. Astourian, a history professor at University of California, Berkeley, the link between DRO and the ARF was not proven. In July 1995, Vahan Hovhannisyan, a leading ARF member, and 31 others were arrested and charged with terrorism and planning a violent government overthrow.

1995 Constitutional Referendum

Armenia’s first constitutional referendum took place on the same day as the vote for parliament, on July 5, 1995. Until the new constitution was adopted, Soviet Armenia’s 1978 constitution was effectively still in place, though it was heavily amended to fit Armenia’s post-Soviet realities. The turnout for the referendum was 56%, and it was approved with 68% of votes, while 29% voted against it.

The constitution created a strong presidential system and downgraded the role of the parliament. The 1995 constitution gave Ter-Petrosyan the power to dissolve the parliament (renamed the National Assembly, Azgayin Zhoghov) and made him the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Freedom House argued that the new constitution provided the “strongest presidency” among OSCE member states.

In their assessment of the referendum, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly observer delegation said it was “free but not fair.”

Elections

1991 Presidential Election

Armenia’s first presidential election took place on October 16, 1991. Ter-Petrosyan was the obvious favorite, but the running field included several prominent figures. Paruyr Hayrikyan, a Soviet-era pro-independence dissident and leader of the National Self-Determination Union party, was his main challenger. Other candidates included Sos Sargsyan, a beloved film and theater actor, who was nominated by the ARF; Ashot Navasardyan of the then-minor Republican Party of Armenia; Rafayel Ghazaryan, another early member of the Karabakh Committee, who ran as an independent; and Zori Balayan, a Karabakh-born writer who rose to prominence in 1988. Ter-Petrosyan easily won with around 83% of the voters backing him, while Haryikryan received only 7% and Sargsyan 4%. This election is widely considered to have been the only unrigged election until 2018.

1995 Parliamentary Election

The first parliamentary elections in independent Armenia took place on July 5, 1995. 190 seats were contested in the election, with 40 allocated to party lists and 150 for single-mandate district constituencies. Out of the 13 that ran, five blocs and parties passed the 5% threshold. Ter-Petrosyan’s Armenian National Movement led the Republic Bloc, which won 43% of the popular vote and received 20 of the 40 proportional seats. The runner up of the election was Shamiram, a party of women, mostly wives of officials, established two months before the election, which received 17% of the vote and 8 seats. The Communist Party won 12% of the vote and 6 seats, while the National Democratic Union, led by Vazgen Manukyan, and National Self-Determination Union led by Paruyr Hayrikyan received 7.5% and 5.6%, respectively, and three seats each.

Candidates affiliated with Ter-Petrosyan’s ANM won the vast majority of single-seat constituencies. Overall, the ANM controlled 160 of the 190 seats in parliament, giving it absolute legislative power. The turnout stood at 54%, but as much as one fourth of ballots were declared invalid. International observers from the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly delegation said the elections “may only be considered by international standards as generally free but not fair.” The delegation detailed some specific problems and violations of the electoral process. The ban on the ARF—as opposed to individuals accused of crimes—“resulted in the removal of a major opposition voice from the elections process.” There were numerous reports of violence and intimidation and voter lists “appeared to be grossly outdated and included large numbers of voters who no longer reside in those districts.” The OSCE delegation also complained of the lack of training of polling station workers.

1996 Presidential Election and Protests

The presidential election on September 22, 1996, was a two-way race between Ter-Petrosyan and his former ally Vazgen Manukyan, who had become his chief rival. Vazgen Manukyan, who was the candidate of the unified opposition, was also backed by the banned ARF. The other candidates were Sergey Badalyan, leader of the Communist Party, and Ashot Manucharyan, another former ally of Ter-Petrosyan from the Karabakh Committee. The final results released by the Central Electoral Commision declared Ter-Petrosyan the winner with around 647,000 votes or almost 52%. A second round was avoided by a margin of a mere 22,000 votes. Manukyan received nearly 516,000 votes or 41.3%. International observers noted that electoral irregularities were sufficient to question the official results, especially because the margin of Ter-Petrosyan’s victory was so narrow. Particularly concerning for observers was the discrepancy of around 22,000 (the same number as Ter-Petrosyan’s vote over 50%) between the number of people who voted and the voter coupons that were deposited.

Both Ter-Petrosyan and Manukyan claimed victory. It became the first in a series of presidential elections after which opposition candidates launched large demonstrations in protest of allegedly rigged elections. On the following days, large crowds gathered on Freedom Square near the Opera Theater, which culminated in violence on September 25. Opposition protesters broke into the parliament building on Baghramyan Avenue, home to the Central Electoral Commission, and beat up Ter-Petrosyan allies parliament Speaker Babken Ararktsyan and Vice Speaker Ara Sahakyan. This incident was used to justify the crackdown on the protests. Defense Minister Vazgen Sargsyan famously declared: “After this, we would not let them come to power even if they had won 100 percent of the vote.” Sargsyan and national security minister Serzh Sargsyan claimed in a televised speech that government forces had prevented a coup attempt.

Thereafter, Ter-Petrosyan declared a state of emergency, while troops and armored personnel carriers came to Yerevan to restore order and quell the demonstrations. In a show of force, protesters were beaten and shots were fired above their heads. Anti-government politicians and activists were beaten and arrested, while party headquarters closed down. The case was taken to the Constitutional Court, which after deliberations on November 22 rejected the appeal by Manukyan and Manucharyan for a repeat vote.

Nagorno-Karabakh Negotiations

Ter-Petrosyan was Armenia’s leader through the entirety of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War that had turned into a full-scale war with Azerbaijan by 1992. A ceasefire was signed in May 1994 and established de facto Armenian control of most of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) and most of the surrounding seven districts.

During the war, there were several attempts at an armistice. In May 1992, while Armenian forces were planning an attack against Shushi, Ter-Petrosyan flew to Tehran, the Iranian capital, to negotiate a deal with the Azerbaijani leader Yakub Mamedov and Iranian President Rafsanjani. A trilateral agreement was signed on May 7, but further negotiations collapsed on May 9, when Armenian forces captured Shushi. At the time, the position of the Armenian government was that it was not involved in the war, only supporting the Armenian cause in Artsakh.

Negotiations over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict were institutionalized in 1994, when the Minsk Group was formed by the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE, now OSCE) and became the main platform for the talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan. At the December 1996 OSCE summit in Lisbon, all member states except Armenia agreed to a draft statement prepared by the Minsk Group which put forward three main principles for the settlement of the conflict. It sought to settle conflict within Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, give Nagorno-Karabakh the “highest degree of self-rule within Azerbaijan” and guarantee the security of Nagorno-Karabakh and its population. Putting Nagorno-Karabakh back into Azerbaijani control, regardless of promises of autonomy, was unacceptable for Armenia and Ter-Petrosyan vetoed the proposal.

In September 1997, Ter-Petrosyan agreed to what has become known as the step-by-step approach, proposed by the Minsk Group. On November 1, 1997, he published his famous article “War or Peace?”, in which he argued that Armenia and Artsakh have no allies in pushing the independence of Artsakh and the only solution to the conflict is a compromise with Azerbaijan. As its name implies, the approach called for a phased solution. First, Armenian forces would withdraw from the districts outside the former NKAO, borders would reopen and economic and transport ties would be re-established, and only after that the status of Nagorno-Karabakh would be determined. Ter-Petrosyan argued that Armenia and Artsakh have the upper hand and were stronger than ever and should use the moment to settle the conflict in their favor. The approach was unacceptable for the leadership of Artsakh, and some of Ter-Petrosyan’s closest allies, including some of his own cabinet members: Prime Minister Robert Kocharyan, Defense Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and Interior and National Security Minister Serzh Sargsyan. At a Security Council meeting in January 1998, the divide became evident. Kocharyan and Vazgen Sargsyan led the attack on the plan. Left with little choice, Ter-Petrosyan resigned from office on February 3, 1998. In his resignation address, Ter-Petrosyan said, “the party of peace and dignified reconciliation has lost in Armenia.”

Diplomacy

After Armenia declared its independence in September 1991, other countries began to recognize its independence and establish bilateral diplomatic ties. The first two countries to establish formal diplomatic relations with independent Armenia were Lithuania (November 21, 1991) and Romania (December 17, 1991). Turkey officially recognized the Republic of Armenia on December 24. By the end of 1992, Armenia had established formal diplomatic relations with some 75 countries.

During Ter-Petrosyan’s presidency, Armenia joined several regional and international organizations. Armenia joined the United Nations on March 2, 1992, on the same day as seven other former Soviet states. Earlier, on January 30, 1992, Armenia had become a member of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), which in 1995 became the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) that now brings together 57 nations in Eurasia and North America. Membership in the OSCE is significant for Armenia for several reasons, but two stand out. Firstly, the OSCE Minsk Group, founded in 1994, has been the main forum where negotiations over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan take place. Secondly, the OSCE has been a major player in observing and assessing elections and human rights in Armenia. Notably, the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) has observed all nationwide elections and referendums in Armenia since 1996.

Armenia joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) on December 21, 1991. It is a loose coalition that brings together nine of the fifteen former Soviet states. On May 15, 1992, Armenia joined Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan to sign the Collective Security Treaty, which led to the creation of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) a decade later. Armenia also established relations with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1992, when it joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (now called the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council). It made Armenia an ally and/or partner of NATO. Armenia joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme in 1994.

In June 1992, Armenia signed the Bosphorus Statement, which led to the establishment of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) in 1994. It had 11 original members, including Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Economy

In the early 1990s, Armenia’s economy experienced major changes and challenges. With the centrally-planned economy of the Soviet Union gone, the country’s economy collapsed dramatically. In 1992, the first year of full independence, Armenia’s GDP dropped by some 42%. The economy only began to recover slowly in 1994.

The ongoing fallout from the 1988 Spitak earthquake (which obliterated approximately 25% of Armenia’s industrial sector), the shut down of the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant (which provided about 40% of the country’s electricity), the transition to a Western-style market economy following independence, the ongoing conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh which turned into an all-out war, mass privatization schemes and flourishing corruption by some elements in the ruling elite decimated the economy. These were compounded by the blockade of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh by Azerbaijan (Armenia imported approximately 80% of its fuel supplies from the USSR, 82% of which was produced in Azerbaijan.) The impact of the blockade was aggravated when Turkey imposed its own blockade of Armenia in 1993. Civil strife in neighboring Georgia (1992-93) also disrupted transit routes that were vital to Armenia, leading to an energy crisis that came to be known as the “cold and dark years”.

Ecology

Environmental concerns were one of the first public concerns to be discussed and protested in the late 1980s. In the fall of 1987, months before mass protests for the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Soviet Armenia began, several small but significant demonstrations took place in Yerevan raising ecological concerns in the capital and the safety of the nuclear power plant in Metsamor, Armenia’s sole nuclear power plant. It was closed down in 1989 due to environmental concerns associated with the 1988 earthquake and the Chernobyl disaster of 1986. Its closure caused, among other reasons, a massive electricity shortage in Armenia through that period.

In the 1990s, due to the energy crisis, the water of Lake Sevan was exploited for hydropower generation on the Hrazdan River. Between 1992 and 1998, Sevan’s level dropped by more than a meter. It caused instability in its water level, which had begun to recover in the 1980s after the completion of the Arpa-Sevan tunnel.

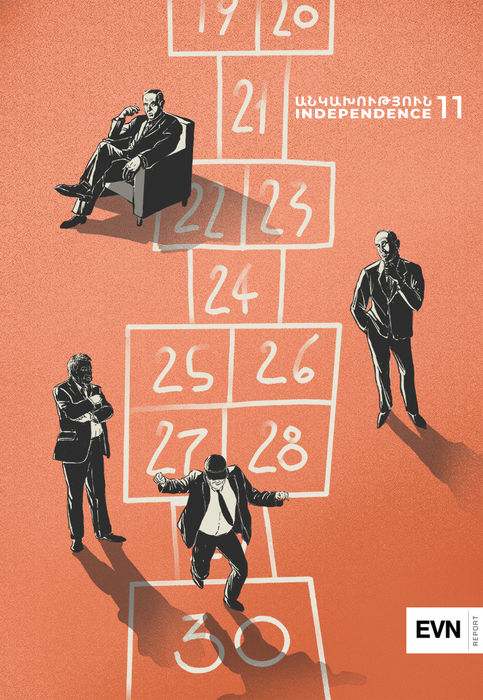

Illustration by Harut Tumaghyan.

Independence | N11

The Republic of Armenia marks the 30th anniversary of its independence on September 21, 2021.

As the Soviet Union was collapsing, the Supreme Council of the Armenian SSR adopted a Declaration of Independence on August 23, 1990. On September 21, 1991 a nationwide independence referendum was held. Independence was officially declared by parliament two days later.

Marking a milestone independence should be celebratory, but in the shadow of the 2020 Artsakh War, it is one that will be marked with mixed feelings and uncertainty about the future.

EVN Report’s 11th magazine issue entitled “Independence” looks back over the four administrations of independent Armenia, revealing their major challenges and hurdles, their setbacks and successes. Over four days, we will cover Armenia’s first President Levon Ter-Petrosyan (1991-1998), second President Robert Kocharyan (1998-2008), third President Serzh Sargsyan (2008-2018) and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan (2018-2021). As bleak as the future seems today, understanding the past is the first step to forging a brighter path for the fourth decade ahead.