September 27, 2020, unraveled into a 44-day battle for life and death for Artsakh, Armenia and Armenians. True to journalistic idiosyncrasy, many of us set out to witness, record and convey to the world the horrors of an assault on peaceful citizens and on justice and humanity. Little did we know we would “fail,” even if subtly, especially when the world responded with logical fallacies, under the cover of false equivalence. In the post-truth era, reporting is just another “clickable” story in a sea of disinformation, misinformation, daily official briefings and social media posts all amid a deficit of real information: “Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink.”

It was war and we did what we knew, maybe we should have known more.

To be fair, many of us were covering press conferences in hotel lobbies a day before and suddenly found ourselves covering conflict. I, and many like me, were not war reporters and having covered our own war does not make us one. How to report with journalistic integrity when you are a side to the war, when you are at war, under attack? How does one deal with their own patriotism? The journalistic code of ethics instructs us to “do no harm”, but do we do that by reporting or not reporting events we witness in all of their reality or do we censor ourselves by cutting out some of the harsher realities? Much of the population had already left Artsakh by September 28. Stepanakert was technically a ghost town a week into the war with mainly the mothers of soldiers, the sick and the old left behind in bunkers; some soldiers were already deserting their posts…would anyone have been better off knowing all this sooner, less angry at the end?

As Vardan Hovhannisyan from Bars Media says, “You should think about the dilemma before the war, not after. Our mistake was that we did not prepare for war like armies do. As journalists and filmmakers we think, ‘well, when war starts, we will go and everything will be in front of us.’”

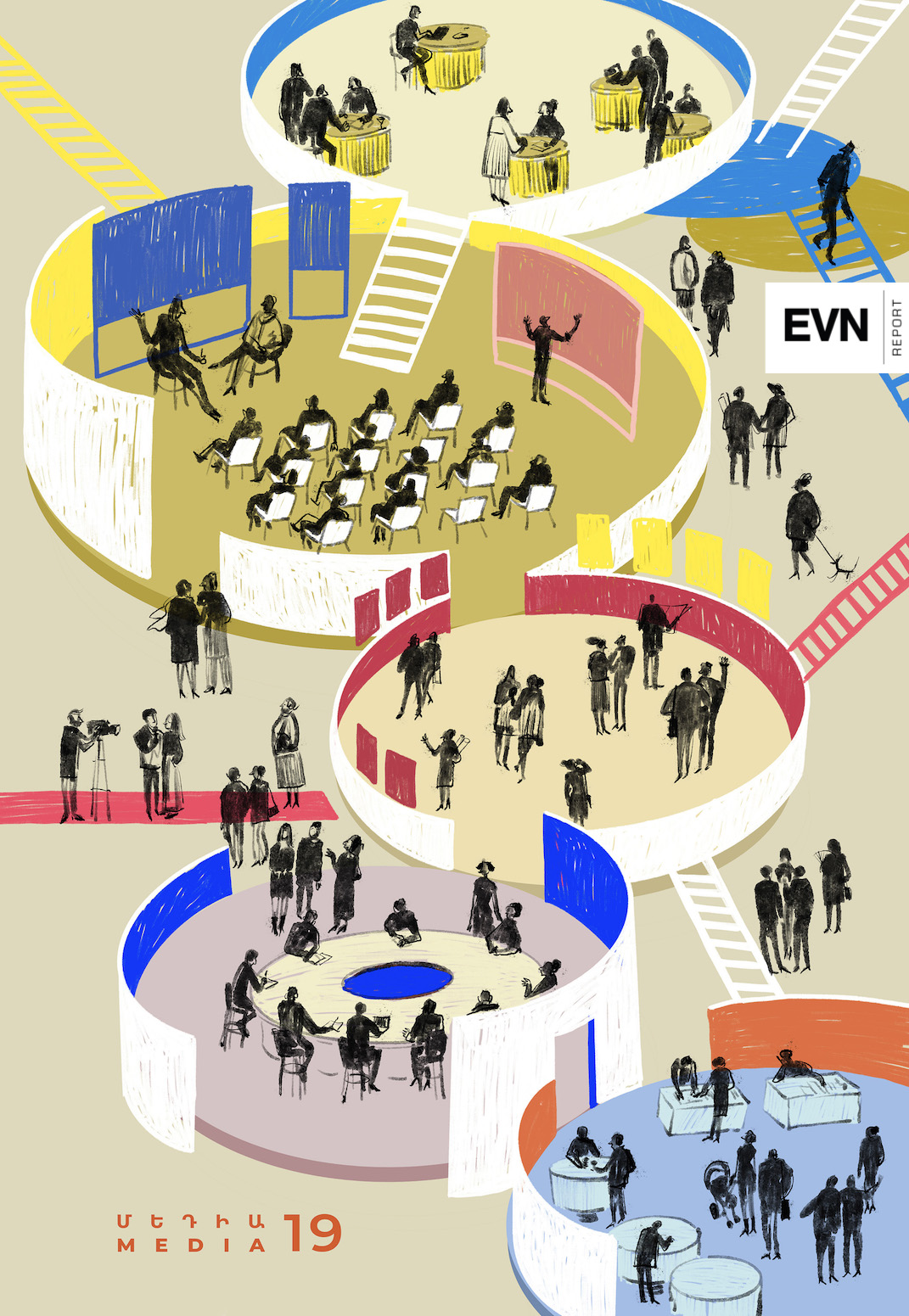

The panel discussion on War Reporting during EVN Report’s Media Festival was an attempt at post-truth, post-war collective and public introspection.

The Dilemma is Multifold

Media globally is changing and so are wars. And the way we tell the story needs to change.

Wars unravel quickly and as journalists on the front we are always right behind events. You can only be in one place at a time and most often that place and time is the target of the next air strike. Dozens of us take the same images, report the same incident, and chase the same stories with the same frenzy and purpose. At what point do you pause and reconsider, put aside the professional fear of missing out and rethink your storytelling?

Augustinas Šulija, a multimedia journalist and foreign news editor at Lithuanian National Broadcaster LRT worked in Artsakh during the 2020 war. He also later went to Ukraine to cover the war, and says that in Ukraine, they decided not to chase breaking news. “For sure Reuters is going to be faster than you,” he explains. They made a conscious decision to find “slower stories.”

Artsakh was different, Šulija says. From the first hours of the war, it became clear that Armenia was ready and open for journalists to come: “For me, it was something new –– usually it’s the other way around. It was something very helpful in the situation and allowed very quickly to get engaged, understand and feel the atmosphere and engage with people and officials.”

Dilemma: Access and Perspective

The 2020 Artsakh War was different for those of us who were not there to tell a story for an audience with no relationship to the conflict nor to its geography and history. Access for us who were there to witness and document truths in intricate detail and to create a record that would inform our own narrative and hopefully rectify the world’s, was denied.

Angela Frankyan, a documentary filmmaker who was in Artsakh when the war started and who stayed to document first and tell the story later, says it was not only about access—being allowed to report from the hospitals, to visit the frontlines, talk to soldiers—most of the population saw people with cameras as a threat. We were often seen as an foreshadowing of air strikes, a bad omen. We film, the enemy sees, the enemy strikes.

But back to access. Angela offered to volunteer as a fixer for foreign media, to translate when needed to be able to have access, which she said she understood was relative. During wars everything is constantly shifting and you don’t know if you can go back to the place you were a day before. You constantly feel unsatisfied. “Maybe I did not film enough. I could have done more and I did not,” she says.

Frustration and Post-war Syndrome

“There are two timelines when it comes to war reporting,” says Laurence Cornet, a photo editor for Le Monde. One timeline is when you collect material to make sense of it later, and the other is “urgency time,” bringing the story to the news that day. Even then, you need to step back for a moment to get the bigger picture.

War does not end with the end of hostilities––the story continues, so does the storytelling. “We encourage everyone to actually revisit their [photo] archive a few months and a few years later because then the story keeps unraveling,” says Cornet.

Post-war syndrome is what this panel conditionally termed the guilt each of us has when it comes to archives that burn your conscience and remind you of a responsibility unfulfilled. You have what you have; your last photo of Shushi is your last photo of Shushi regardless of whether it is a good photograph or not. What to do with it, if anything?

Angela found a way back into her own story, when she revisited the person who saved her life when a group of journalists were targeted in Martuni. “Maybe that is how I can get out of this survivor’s guilt, that is how maybe I will save this archival material for which I had risked my life,” she says.

When you are on the frontline you should [be able to] answer the question, “Why am I here, what is my mission, what is my real mission ––and not what you would like to do?” says Vardan Hovhannisyan, a veteran filmmaker who has covered our wars and the wars of others. “During the first [Artsakh] war I was an idealistic 20-year-old, there to make a meaningful film about war.” While on his mission to make the film, Vardan became a POW twice, escaping from captivity the first time and being exchanged for another POW the second.

Why Am I Here?

Finding meaning in your own presence as a witness, even when you are the designated storyteller and not a soldier is not straightforward. Especially when your people are under attack, the sons of your friends are on the frontlines and you are physically in danger.

“When you enter a house that has turned into rubble, where people have died, it is a constant internal battle to continue to decide that you might have helped by photographing,” says photojournalist Vaghinak Ghazaryan. He adds that it is true that for some it is easier to be there as part of it all at the moment, harder to be away.

Ghazaryan’s photograph, “The Resting Soldier” won 3rd prize in the 2021 World Press photo contest, in the Contemporary Issues category. The photograph is of a soldier sleeping in the trenches. He would have been hard to see if not for the plastic tarp underneath him keeping him dry from the moist earth, with which he would have otherwise been camouflaged.

It is an image that tells many untold stories. Yet the author says he headed to Artsakh with his camera and his military booklet not knowing which one he would end up using.

“During the four years of the first war I never carried a weapon. The weapon became an option during the 2020 Artsakh War. At one point I was thinking of quitting filming and joining the army. I had a weapon as a backup to my camera.” This is realism as Vardan calls it.

Augustinas echoes Vardan’s sentiments: “All my life I declared that I would never pick up a gun, I do not want to shoot at anyone ever, it was a very strong feeling that I always had but Artsakh changed that.” He says it is the repeated story of a small country being attacked brutally and left to fend on its own, not unlike Lithuania and the stories of self defense that he grew up hearing.

Is any story worth telling if the price is death or health, when all you have walked away with is a failed mission to petition the world to see the facts. Or maybe the conjecture of “failure” is simply a reflection of the times we live in. If we need the world to care about our wars, we need to learn to care about the wars of others. And if we need to be heard or seen we need to find a new language with which to talk about war.

Is it possible to be a neutral observer when the war is happening in your country? How do journalists prepare to go to the frontline to cover a war? Were Armenian journalists prepared for the challenges and obstacles of reporting on the 2020 Artsakh War? What about physical safety? Moderator: Roubina Margossian, EVN Report

Panelists:

Augustinas Šulija, Lithuanian National Broadcaster LRT

Vardan Hovhannisyan, Bars Media

Laurence Cornet, Le Monde

Angela Frangyan, filmmaker

Vaghinak Ghazaryan, Photojournalist

The panel was filmed and edited by Hetq Media Factory.

Issue N19

The Editors

During EVN Report’s Media Festival, a group of editors from different media outlets were invited to discuss the challenges and opportunities in working in an ever-changing, fluid and unstable environment.

Read moreThe Armenian Start-Up Ecosystem in National Narratives

Young people in Armenia can use start-ups as a vehicle to impact change and disrupt the status quo not only in their country, but also for solving global problems despite overwhelming challenges.

Read moreThe Malice of Politesse: On the Critical Condition of Cultural Criticism in Armenia

Only in nurturing the growth of critical thinking can we strengthen the positions of our cultural identity and its continuing relevance in the increasingly chaotic geopolitical and technological tides of the 21st century.

Read more