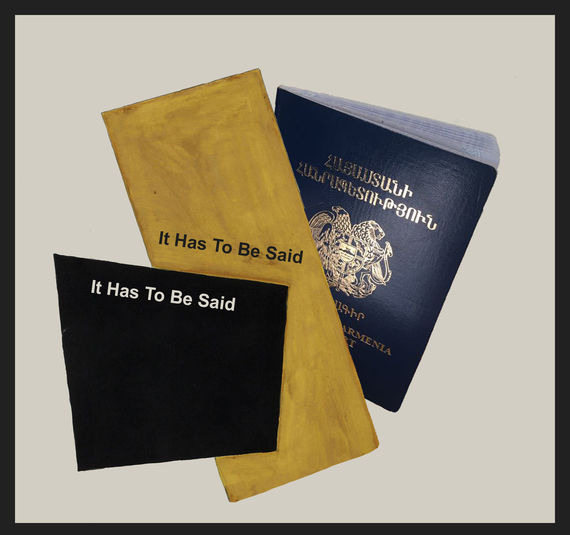

This week, the country’s leadership woke up to the fact that acquiring Armenian citizenship was a massive headache for diasporans. No kidding. Countless diasporans (including yours truly) have had to endure the agonizing, dizzying, frustrating, near-stroke-inducing experience. There may be an untapped market need for psychologists to treat the post-traumatic stress disorder that inflicts those who have had to go through the bureaucratic nightmare – a term the Republic of Armenia could copyright.

Let me explain.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan received a letter this week from a woman who moved to Armenia from Canada with her family following the Velvet Revolution. She complained at length about the maze of red tape she had to navigate at the Visa and Passport Office (OVIR) in her quest to become a citizen of what was, in her heart, her native country.

Pashinyan, finding the ordeal unacceptable, published the woman’s letter on his Facebook page (with her permission). He demanded that the Deputy Prime Minister, Chief of Police, Minister of Justice, High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs and his Chief of Staff look into the matter. He even publicly directed the police chief to fire employees who are working “badly.”

No matter who gets fired at OVIR, it will not solve a problem that goes much deeper and cuts across all state agencies and bodies.

But first, let’s get back to the story.

The woman, who was actually born in Armenia, had lost her citizenship when she left the country in 1999, before the law on dual citizenship came into force. She had married in Canada and taken her husband’s last name. Consequently, she was required by OVIR to provide proof that she was who she said she was; in other words, they could not confirm that she was born in Armenia until she brought proof of her name change via an official document from Canada with an apostille. Canada is not a signatory to the Hague Apostille Convention and, therefore, does not issue apostilles for their official documents. The bureaucrats at OVIR showed little concern that this requirement was an insurmountable obstacle for this woman to overcome. In fact, some apparently even went so far as to rudely ask her why she had bothered to move to Armenia in the first place, declaring that “the Prime Minister has tricked us all.”

I want to believe that the Prime Minister’s motivation in raising the issue by writing a status on his Facebook Page came from a place of genuine concern, given the fact that he keeps appealing to diasporans to return to the motherland (as opposed to giving an order to fire an underpaid, uninspired, ineffective and I dare say incompetent bureaucrat who felt “tricked”).

The broader issue at hand, therefore, is the bureaucracy itself and the people who work there.

The Law on Civil Service was adopted on December 4, 2001, and was meant to ensure the rights of civil servants were legally protected, that professionals in their respective fields could take on roles in the state apparatus without fear of being arbitrarily fired without just cause simply because a new political force came into power (as had been the practice). It was meant to establish a well-balanced human resources policy and mitigate corruption risks. Frankly, I remember applauding the decision, but there was so much I didn’t understand about the ethos of Armenia’s bureaucracy back in 2001.

The same law makes it extremely difficult, virtually impossible, to dismiss a civil servant, even when poor performance normally would provide just cause. A supervisor would need to provide the following notices in writing: i. warning; ii. reprimand; iii. severe reprimand; iv. decrease in salary prescribed by law; and only then dismissal by consent of the Civil Service Council. The process involved is so arduous and burdensome that a minister or head of a state agency realizes it is a fight they are not likely to win and definitely not one worth draining their capacity when there are figurative fires they need to focus on putting out.

And that is where the problem lies.

Everyone is talking “off the record” about what is clearly a problem that stands in the way of efficient governance and productivity – an incompetent civil service (there are exceptions to be sure). Yet, no one is talking about it “on the record.” We have a bureaucracy that has ballooned in numbers with each successive administration. Public sector jobs were used as a way to reward political allies and build out a bribery funnel that used to go all the way to the top.

When Serzh Sargsyan resigned, that apparatus remained in place. The post-Velvet administration of mostly-new, mostly-inexperienced cadres still relies on a civil service that has an entrenched culture of pernicious practices. To expect that these attitudes would all suddenly disappear on their own after the spring of 2018 is naive at best.

And thus, no one who has interacted with the system was particularly surprised by this treatment of a diasporan by a bureaucrat at OVIR. We could have told you about it, and we did, except that, before, no one was listening. Hopefully, this incident will spark a process to reexamine the sometimes obtuse regulations to obtain citizenship. Once upon a time, a broken system may have been desirable if it helped to exasperate an otherwise-honest applicant into finally greasing the palms of an intransigent bureaucrat. To everyone’s relief, those days are now behind us. We don’t need to humiliate those who are willing to bring their financial and human capital to help in the country’s rebuilding process. Instead of insulting this woman, a transformed civil service would be the first to offer solutions, even in areas that require legislative reform. Such a transformation won’t happen overnight but it is needed across every government agency, not just at OVIR.

There was a time when this woman’s letter would have been thrown in the trash. She would have returned to Canada and warned all she met not to take the risk that she did. Though one Facebook post won’t change things immediately, it does attest to the fact that the needed transformation at least has begun.

And hopefully, those of us who had to endure the nightmare of acquiring citizenship, which often bordered on humiliation, will be the last in contemporary Armenia to have experienced such behavior.