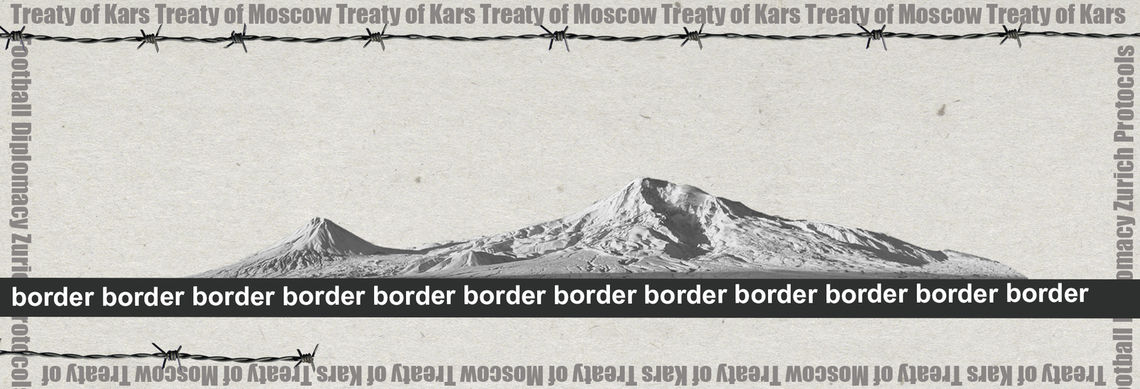

With guard towers, closed crossings, and regular armed patrols, the present-day border between Armenia and Turkey would strike many as a relic of the Cold War. Although the product of a demarcation process just over a century ago and decades of Soviet rule, the closure and sealing of the border after 1991 was largely the result of political factors and has led to an ongoing series of stresses on modern day Armenia. This ranges from the strain of the ongoing economic blockade to the physical separation of Armenian travelers from Mount Ararat and ancestral lands in what was Western Armenia. This article will provide a brief history of the Armenian-Turkish border spanning from Armenia’s incorporation into the USSR to the present day. This piece will also touch upon the “Zurich Protocols” – a proposed treaty that would have normalized and opened Turkey’s border with Armenia – and reflects on the viability of a future normalization process.

The Treaty of Moscow, the Treaty of Kars

In the wake of the First World War, the Ottoman and Russian Empires’ control over the Caucasus had receded and in this vacuum emerged the First Republic of Armenia. With Yerevan as its capital, the First Republic of Armenia covered what are today the Republics of Armenia and Artsakh, as well as the territories of Kars, Nakhichevan, and Mount Ararat. The fledgling states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia engaged in a series of skirmishes and minor conflicts while the newly formed Soviet Union and Republic of Turkey sought to reclaim influence in the region. After two years of independence, the lands of Armenia were again divided between Istanbul and Moscow following the 1920 Turkish-Armenian War and the later Red Army invasion of Armenia.

With the First Republic of Armenia bisected by Soviet and Turkish troops, Turkey and the USSR negotiated what would be known as the Treaty of Moscow in the spring of 1921. In addition to establishing friendly relations and other basic forms of diplomatic contact between both governments, the agreement was largely designed to demarcate the historically turbulent region of the South Caucasus and prevent a future territorial incursion by either party. As neither the Soviet Union nor Kemalist-Turkey were recognized by the international community, the agreement was also key in legitimizing the governments of both Vladimir Lenin and Mustafa Ataturk as political actors with full agency to conduct foreign affairs.

This was later followed by the Treaty of Kars – a nearly identical agreement signed later that year that was designed to reiterate the territorial demarcations referenced in the Treaty of Moscow. According to the treaty, all land west of the Araks and Akhuryan rivers would be ceded to Turkey while all land east would be incorporated into the USSR. Under this demarcation Mount Ararat fell just outside the borders of Soviet Armenia along with the cities of Ani, Kars and Van – all of which were of great cultural and historic importance. While elements of the Soviet leadership had protested this allocation of land and proposed future territory swaps with Turkey, the terms of the Treaty of Kars were largely unchallenged. It is worth noting that the Soviet signature on the Treaty of Kars was divided between the constituent republics of the USSR – meaning that the Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian Soviet Socialist Republics were considered individual signatories of the treaty, with the Russian Federal Socialist Republic largely acting as an intermediary. As a result, the treaty would be used to establish territorial boundaries between Turkey and the USSR but would also be used in establishing Turkey’s borders with Armenia and Georgia after the collapse of the USSR.

A Soviet Border

In the years following the Treaty of Kars the western borders of the Armenian and Georgian SSRs would represent the Soviet Union’s international border with Turkey. While relations between both countries would dip after Turkey’s decision to join NATO in 1952, the Soviet-Turkish border never reached a level of militarization like the Iron Curtain. When looking at potential military activities across the Soviet-Turkish border, the Armenian SSR was not necessarily considered to be a point of contact between Turkish and Soviet forces. One of the main reasons for this was the greater strategic importance of the Black Sea compared to the rocky highlands of the South Caucasus. The Soviet Union considered Georgian ports like Batumi and Poti to be of high military and industrial importance. Additionally, infrastructure like the Georgian Military Highway and Abkhazian segment of the Transcaucasian Railway provided a high degree of accessibility from the Georgian SSR to the rest of the Soviet Union. In comparison, Armenia’s rocky geography and remote location from the core of the USSR made it a less-ideal location for a strategic foothold. There was also the reality of disparities between Turkey’s eastern territories and the Soviet Union’s holdings in the Caucasus. According to a declassified CIA Report from 1952, the Armenian and Georgian side of the Turkish-Soviet border was considerably more developed than the territories of Eastern Turkey. Cities like Tbilisi and Yerevan were described as major centers of population and industry in the Caucasus, while Turkey’s eastern provinces were under developed and sparsely populated. For both the Soviet Union and Turkey, the territories of the Caucasus were a largely underdeveloped periphery

But that is not to say that both countries were without their tensions. The Turkish Straits Crisis led to an ongoing diplomatic standoff between both countries after Turkey denied the Soviet Black Sea Fleet access to the Mediterreanean Sea. The stationing of Jupiter Missiles by the United States in Turkey was considered to be a major provocation from Istanbul and Washington by the USSR and contributed to what would eventually become the Cuban Missile Crisis. With these conditions in mind, the Red Army maintained a presence in the Caucasus and designated the region as the “Transcaucasian Military District.” While Georgia was an area of great strategic value due to its aforementioned Black Sea coastline and military highway, the 127th Motor Rifle Division of the 7th Guards Army was stationed in Leninakan (present-day Gyumri) and designated with patrolling the border of the Armenian SSR and Turkey.

During this period, limited movement was possible across the Soviet-Turkish border. A wide-gauge rail line constructed in the 1800s ran from Gyumri (then Leninakan) to Kars. This line was not designated for passenger use, but mostly used for the movement of freight between Turkey and the USSR. While a gauge-break between the Turkish and Soviet rails required carriages crossing the border to be lifted and their wheels swapped, the line was still frequently used with roughly 65,000 tons of freight crossing the border at its peak in 1984. While smaller crossings for persons did exist, most passenger traffic was directed through Georgia.

Independent Armenia

After gaining independence from the Soviet Union Armenia’s border with Turkey became one of the country’s four international borders. While Armenia’s conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh began during the dissolution of the USSR and carried over into the independence period, relations with Turkey were surprisingly cordial in the early 1990s. During this period the two possible points of crossing the Armenian-Turkish border were the Dogu Kapi-Akhourian border gate and the rail crossing between Kars and Gyumri. Limited travel was possible and at one point a group of Armenians traveled on a pilgrimage to the city of Ani via the Gyumri-Kars railway.

However, this period openness was brief. In 1993 Turkey sealed its border with Armenia to all traffic as a demonstration of solidarity with Azerbaijan after the Battle of Shushi and scuttled any efforts to establish diplomatic relations with Yerevan. This created an economic blockade and limited Armenia to conducting all international trade via Iran and Georgia. This limit on international trade compounded Armenia’s economic woes, as the country was still recovering from the Spitak Earthquake and navigating a complex transition towards a market economy. Beyond its status as a major economy in the region and potential trading partner, Turkey would have been a key conduit for Armenian trade with Europe. Existing agreements like the EU-Turkey Customs Union would have facilitated Armenian trade with the participants of the European Union’s Single Common Market through its border in Turkey. Currently, any trade between Armenia and the European Union must travel north through Georgia towards the Poti, where goods would be then shipped across the Black Sea. For several years Turkey’s blockade of Armenia also included a ban on any travel into Turkish airspace, effectively making commercial flights between both countries impossible. This limit was eased however, and seasonal and charter flights between Istanbul and Yerevan were made possible.

By 1993, Armenia was caught in a vice between the ongoing war with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh and increasingly poor relations with Turkey. With a pressing need for some type of assurance of security, Armenia turned to the Russian Federation. At the time Russia was experiencing many of the same economic shocks as Armenia and its influence in the South Caucasus had been steadily receding. However, the country was still a major influence in the region and would be capable of providing a counterweight against Iran and Turkey. During a transition period after the dissolution of the USSR, former Red Army garrisons in the South Caucasus were placed under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) yet still largely coordinated by Moscow. In response to threats from the Turkish government regarding intervention in support of Azerbaijan and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakichevan, Commander of CIS Military Forces Yevgeny Shaposhnikov issued a warning, stating that with such action “we shall be on the brink of a new world war”. In 1995, Armenia and Russia signed a treaty on cooperation in defence and security which included the formal establishment of a Russian military base in the city of Gyumri known as the 102nd Military Base. This was followed by a 1997 Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance which would form the basis of Armenian-Russian relations and would later be revised and expanded. In addition to Armenia’s participation in the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization and the presence of both a Russian base in Gyumri and military airport in Yerevan, Moscow’s security assurances to Yerevan include an agreement that Armenia’s frontiers with Iran and Turkey would be patrolled by units of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs. Although the presence of the Russian military may have diffused the threat of conflict with Turkey in the years following the Battle of Shushi, it was effectively an indefinite remilitarization of the Armenia-Turkey border.

Football Diplomacy and the Zurich Protocols

While Armenian-Turkish relations remained frigid throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, this would change during a brief period of what would later be known as “Football Diplomacy.” A World Cup qualifying match was to be held in Yerevan’s Hrazdan stadium between the Armenian and Turkish national teams. To the surprise of many, then-President Serzh Sargsyan extended an invitation to Turkish President Abdullah Gul to visit Yerevan on the occasion of the match, during which meetings would be held between both presidents and their respective MFAs. Considering that Gul was the first Turkish head of state to visit the Republic of Armenia, this meeting was considered a major development in Armenia-Turkish relations and signaled a potential thaw in relations.

The visit was not without controversy. Large crowds of demonstrators flocked to Hrazdan during the match and protests were organized throughout Gul’s visit in response to Turkey’s ongoing denial of the Armenian Genocide. At the core of these protests was Turkey’s ongoing denial of the Armenian Genocide. As the primary organizers of the demonstration, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF-Dashnaktsutyun) reiterated that no bilateral ties would be possible without genocide recogniton and that the protest of Abdullah Gul’s visit was in line with similar demonstrations held by members of the Armenian diaspora throughout his visits in Europe. Gul and Sargsyan’s conversation was mostly grounded in bilateral relations and broader developments in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. From all available information, genocide recognition was not mentioned during the meeting at Hrazdan stadium. In the aftermath of the meeting the governments of both Armenia and Turkey delivered public statements reflecting on the productivity of the visit and a mutual willingness to move forward with improving bilateral ties. This was followed by the announcement of a roadmap to reconciliation between both countries that later be known as the “Zurich Protocols.”

The Zurich Protocols was a proposed treaty between Armenia and Turkey that sought the normalization of relations between both countries. Many negotiations on the treaty were kept secret due to the sensitive nature of its subject matter. The treaty divided this task into two protocols. The first, titled “Protocol on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations,” was the formal establishment of diplomatic relations between Armenia and Turkey. The second, under the title “Protocol on Development of Relations,” was the opening of the Armenia-Turkey border and the creation of interstate working commission between both countries.

It is worth noting that a “normalized” or “open” border does not necessarily mean one that is non-existent. As in the early 1990s, Armenia and Turkey would still control their own policies on visas and travel and would be free to enforce their respective customs standards. However, with a normalized and open border, the complete economic blockade of Armenia by Turkey would be lifted and dedicated points for crossing would be reopened, similar to Armenia’s borders with Georgia and Iran.

Given the sensitive nature of the agreement and potential protests in Armenia and Turkey, the protocols were initially negotiated in secret with Swiss mediation starting in 2007. The announcement of the protocols led to the withdrawal of ARF deputies from Sargsyan’s coalition government. Others criticized the implementation of the protocols, feeling that the agreement was largely the product of outside parties and not in Armenia’s direct national interest. Among the many concerns regarding the agreement was that its drafting and negotiation was largely done in secret and away from public view. There was also the question of how the protocols and potential normalization of relations with Turkey would affect genocide recognition. Some theorize that the President Obama hesitated to use the word “genocide” in the 2009 anniversary of the Armenian Genocide out of caution that it would potentially threaten the passage of the agreement, despite having previously campaigned on the position of genocide recognition. The agreement also drew extensive criticism from diaspora organizations, who felt that the agreement was effectively compromising positions on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenian territorial claims, and genocide recognition.

Among the proposed parts of the intergovernmental commission was the creation of the following:

“[a] sub-commission on the historical dimension to implement a dialogue with the aim to restore mutual confidence between the two nations, including an impartial scientific examination of the historical records and archives to define existing problems and formulate recommendations, in which Turkish, Armenian as well as Swiss and other international experts shall take part”.

It can be inferred that the sub-commission listed above is referring to an “impartial scientific investigation” of the Armenian Genocide. This is not the first time that a joint investigation of the Armenian Genocide had been proposed. In years prior, a Turkish-Armenian Joint Reconciliation Council was created for a similar purpose and in 2005 the Turkish Parliament released a statement supporting the creation of a joint historic investigation with Armenia. But while joint investigations may seem like a step towards progress in genocide recognition, previous efforts have delivered questionable results. Investigations by the Turkish government have conceeded Armenians were killed in 1915, but that their deaths could not be considered genocide and were not as extensive as the 1.5 million figure often cited. Even the Joint Reconciliation Council’s conclusion that the Ottoman Empire did in fact commit genocide did not change Turkey’s stance towards the topic.

On October 10, 2009, the Zurich Protocols were signed by the Armenian and Turkish Ministers of Foreign Affairs and included diplomatic representatives from the European Union, France, the United States, and the Russian Federation. The agreement included the above provision for a joint commission for a historical investigation, but included neither a reference to the status of Nagorno-Karabakh nor the phrase “Armenian Genocide.” While the signing of the agreement was considered a major development in the South Caucasus, sluggishness in the actual implementation of the normalization protocols were already visible one year later. The agreement remained a controversial subject in both Armenia and Turkey and the necessity for both country’s parliaments to ratify the agreement added another potential roadblock. Throughout this period little effort was made by the government of Turkey to begin a normalization process of the Armenian border and ease the economic blockade. In comparison, elements of Armenian government and industry had made preparations for the opening of the border.

The brief period of good-will between both governments following the signing of the protocols quickly faded as passage of the agreement became less and less likely. Although both sides agreed to ratify the agreement without preconditions, the Turkish government stalled its ratification process, stating that the treaty would only be sent to the parliament should major developments occur in the resolution of the Karabakh conflict. This was met with protest from the Armenian government. For the Turkish government, there was also concern that normalizing the border would partially vindicate Armenia’s claims to territory located along the eastern edge of the country. Neither country’s parliament ratified the Zurich Protocols and the treaty was condemned to legal limbo. After recalling the treaty from the parliament in 2015, President Sarksian nullified the agreement on March 1, 2018, citing a lack of willingness towards action from the Turkish government.

The Border Today, Looking Forward

The Armenian-Turkish border remains sealed to all traffic and is still patrolled by Russian forces. Georgia continues to be Armenia’s main conduit for international trade, with poor infrastructure between both countries increasing the costly circumvention of the blockade. With the development of infrastructure projects designed to connect Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia, the ongoing economic blockade isolates Armenia within a region that is increasingly connected to the global economy. The blockade has not only disconnected Armenia from conventional infrastructure projects in the region, but has also impacted the development of telecommunications infrastructure and created a potential digital bottleneck. But Armenia is far from being at fault for this scenario. While Yerevan was steadfast in supporting the signing of the protocols without pretext, Ankara’s insistence that a signature would only be provided following progress on the resolution of the Karabakh conflict was essentially a reiteration of the terms provided during the start of the blockade in 1993. Despite the unilateral blockade, roughly $220 million dollars worth of goods are imported annually from Turkey to Armenia by circumvention through Georgia – much of this figure being plastics, fabrics, cleaning chemicals, and other cheap products.

Developments in Turkey and the surrounding region have cast doubt on the viability of a future border normalization process. President Erdogan continues to shape Turkey into an authoritarian state and maintains popular support through continued usage of nationalist rhetoric. This has included slights and attacks against Turkey’s Armenian population and the continued public denial of the Armenian Genocide. Turkey’s military incursion into Northern Syria, dubbed “Operation Peace Spring,” saw decendents of Armenian Genocide survivers subjected to acts of violence by the Turkish military alongside the country’s Kurdish population, awakening a sense of intergenerational trauma. The operation was supported by Azerbaijan and Pakistan, hinting at the emergence of a strategic triangle of countries who were previously united in support of Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh war. The operation was followed by a statement from President Erdogan, reiterating that Turkey would ensure the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan with regards to the Karabakh conflict. The events of Operation Peace Spring have shown us Turkey’s willingness to use force against its neighbors and in doing so has seemingly cemented the strategic necessity of the Russian military’s presence along Armenia’s western border.

Beyond the Caucasus and Middle East, trends within the international community as a whole may also impact the possibility for future border normalization. While the Zurich Protocols were mainly negotiated between Armenia and Turkey with Swiss mediation, the treaty was still dependent on cooperation between third-party partners for full actualization. The United States and European Union were crucial in keeping Turkey engaged with the negotiation process, while the Russian presence along the border and wider security relationship with Armenia led to Moscow’s inclusion in the process. Since the negotiation of the Zurich Protocols, relations between Turkey and Russia have alternated between periods of rapprochement and conflict in relation to the Syrian civil war. The United States has an ongoing trade dispute with the European Union and President Trump’s personal relationships with Vladimir Putin and Reccip Erdogan often clashes with official American policies towards Russia and Turkey.

With these factors in mind, it seems that the political climate that led to the creation of the Zurich Protocols may never be repeated. Although the blockade and closed border present a challenge to Armenia by no means is the country without options in mitigating its effects. The continued circumvention via Georgia is likely to continue indefinitely, with improvements to infrastructure potentially lessening the cost of this process. Armenia’s inclusion in the Belt and Road Initiative has opened avenues for Chinese funding of infrastructure projects, while the emerging EU-Asia Connectivity Project may provide an alternative model for improving Armenia’s global connectivity. Russia’s expanding presence in key sectors of Armenia’s industry and infrastructure, such as the national railway, hint at a deepening integration between Armenia’s economy and the rest of the Eurasian Economic Union. Amidst all of this lies the ever-green option of resolving the blockade through the rules of the WTO. While this strategy was previously declined and the structure of the organization has complicated this process, it nonetheless remains an option. Similarly, since Turkey is officially an associate of the European Union and potential candidate for future accession (however unlikely as that may seem now), the EU could pressure the country to comply with the “Copenhagen Criteria,” which requires that a candidate complies with the EU standards for market accessibility and barriers to trade. Yet still, at the core of all this political maneuvering is a unilateral blockade by one country against its smaller neighbor and which only the Turkish government is capable of lifting.

Until then, trips to Ararat will have to pass through Georgia.