A study commissioned by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, “Independence Generation Youth Study 2016 – Armenia” provides valuable insights into how the Armenian youth perceive themselves and the world around them. This essay will explore in more detail the section of the study that relates to politics, particularly domestic politics, governance structures, political regime and so on.

Some of the results of the study come as no surprise. In a country with a struggling economy, widespread poverty, migration and a smoldering conflict the young generation names reduction of unemployment, strengthening Armenia’s army, and economic growth as areas the Armenian government should prioritize.

The study also revealed a few interesting patterns that run contrary to what one would expect, and undermine some of the clichés often heard about the independence generation. A few points are elaborated below, exploring young people’s political ideology, Russia-West preferences, the level of political interest in the regions, as contrasted with the capital and perceptions of governance structures. Some tentative recommendations are offered at the end, aimed at stimulating further discussion.

Latent Socialists?

Young Armenians often describe themselves as the new force that parts way with the Soviet past. Unlike their parents, they do not have the Soviet nostalgia and seem to embrace Western liberal ideas, particularly when it comes to the market economy. Or do they? How would we describe the ideology of the Armenian youth?

First of all, it is important to note that the traditional Western “left-right” scale makes little sense to many Armenians.[1] When asked to position themselves on a “left-right” scale in the World Values Survey in 2011, 40 percent of the respondents said “don’t know, ” and another 21 percent chose the middle position (which is often a signal of having no position but not wanting to say that explicitly). The remaining 39 percent of the answers were more or less evenly spread across the spectrum, with a slight tilt towards the right.

The Independence Generation study takes a more nuanced approach. It asks a range of meaningful questions that allow us to understand how the respondents see the role of the state in regulating market relations. Should the state bear greater responsibility for people’s social welfare (a rather socialist attitude) or should people bear a greater responsibility for their own social welfare (a rather liberal attitude)? Should society’s wealth be distributed evenly (a fairly strong socialist attitude) or society’s wealth should not be distributed evenly to encourage competition (liberal capitalist attitude)? Should we increase the state ownership (socialist approach) or the private ownership (capitalist approach) of the economy? Is competition dangerous because it reveals the worst qualities in people or is it a good thing because it stimulates industriousness and creates new ideas?

For the first two questions, most Armenian youth are firmly on the socialist end of the spectrum. According to the study, 64 percent want the state to take more responsibility for the social welfare of the people, with 50 percent choosing the strongest possible option on the position scale; 52 percent want wealth distributed more equally, with 37 percent expressing the strongest possible support for this position. In the case of state ownership vs. private ownership, the opinions are more or less evenly split. The only question where the Armenian youth is clearly on the liberal side of the spectrum is the attitude towards competition as something good: 80 percent of the respondents chose this option, with 47 percent expressing the strongest possible endorsement of competition as a positive phenomenon.

Thus, the only element of the Western liberal ideology the Armenian independence generation has unquestionably embraced is the idea of competition as a positive, creative force. But then again, it is not an entirely new idea. Competition in sports, at school, in volunteering and even friendly competition at work was encouraged during the Soviet Union through various activities and forms of recognition. Taking the four ideology related statements together, we can see that the Armenian independence generation is rather socialist in its thinking. Competition is fine, and many people are in favor of private means of production in the economy, but at least half of the youth wants more state ownership of the economy; most want more state responsibility in providing social welfare and reducing wealth inequalities.

East or West? Russia or Europe?

A misconception often heard from young people is that the independence generation is less pro-Russian, more pro-Western, as compared to the last Soviet generation of their parents. The data, however, suggests something else.

Seventy-seven percent of the respondents of the Independence Generation study are interested in Armenian politics. This comes as no surprise. Next is not the Caucauses, the world, Europe or Turkey. Next, in terms of interest in politics, comes the interest in Russian political events: 52 percent compared to 45 percent interested in international politics and 37 percent interested in European politics. This is a fairly clear signal of what part of the world Armenian youth is watching, regarding political processes.

This fits nicely with data from another survey, the Caucasus Barometer. In 2015, 75 percent of the Armenian people named Russia as the current main friend of Armenia. There was absolutely no difference in how different age cohorts answered this question. Young and old alike see Russia as the main friend of Armenia. No wonder the Armenian independence generation is more interested in Russian, rather than the world or European politics.

75 percent of the Armenian people named Russia as the current main friend of Armenia. There is absolutely no difference in how different age cohorts answered this question.

Politicized Regions

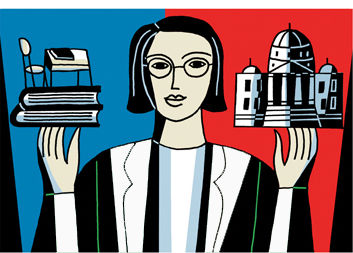

In political science, we often think of urban spaces (and particularly the capital) to be the hub of political activity, interest, knowledge, etc. Partially because urban spaces are where “things happen” in terms of big political events, buildings in which power is concentrated, visits by other country leaders and so on. Partly because urban spaces are saturated by educated and higher-earning individuals, who tend to be more active in politics.

Among the Armenian independence generation, the pattern is reversed: the less educated youth and the regional youth (two categories that probably largely overlap) are more politically active. They are more likely to vote in elections and are more likely to know which party they would be voting for. The authors of the Independence Generation report explain this with clan solidarity, which is stronger in rural communities. That is a very plausible hypothesis indeed. At this point, one is tempted to write a critical statement on how this is bad for the young Armenian democracy because citizens are not making critical choices and instead are following family traditions. Family-based party identification is nothing new or uncommon. It is not a “plague” of the developing world. It has been well-known and documented in the West. Parents’ party identification is one of the strongest predictors of children’s political outlook (see the famous Michigan Model of voting in the U.S. and works of Campbell for example).

The fact that the rural youth is more politically active reflects the overall level of political activity in the regions.

69 percent of rural residents would “certainly participate” if presidential elections were held next Sunday, as compared to 56% of Yerevan residents.

Regional concentrations of party loyalties are also well-known. Think of “red” and “blue” U.S. States, European agrarian parties with strong support in rural areas or the Bloc Québécois in Canada. Both geography and family matter in politics; we see some of it in the opinions of the independence generation.

The fact that the rural youth is more politically active reflects the overall level of political activity in the regions. Caucasus Barometer data shows that the rural residents overall are more active, regardless of age. Sixty-nine percent of rural residents would “certainly participate” if presidential elections were held next Sunday, as compared to 56% of Yerevan residents.

Perceptions of Political Institutions and Processes

Armenian youth is distrustful of most political institutions and processes. The parliament, the president and the political parties (both in power and in the opposition) receive almost equal amount of negative perceptions: more than half of the respondents said they do not trust them at all. The least disliked institution is the local government: 40 percent distrust them completely, the rest trusts somewhat or “a little.” Voting in elections is not seen as an opportunity to make one’s voice count. Sixty-seven percent of the respondents think that their opinion is of little to no importance to the results of political elections. From Caucasus Barometer 2015 we know that 52 percent of people in the age group 18-35 characterized the most recent national elections as “not at all fair.” Given that, it is little surprise that the youth does not think their opinion matters in elections.

Despite distrusting the core institutions of democracy and not believing in the importance of elections[2] the independence generation is rather satisfied with the state of democracy in Armenia. Or are they? Let’s take a closer look at the range of answers. There are five answer options. The one in the middle (“I am satisfied”) received the highest number of responses: 54 percent chose this option. It is a well-known fact that responses to scale-type questions like that often cluster in the middle. People perceive it as a “neutral” option and tend to choose it if they do not have a clear stance on an issue. Do Armenian young people understand what democracy is and what it means to be “satisfied” with how it works? Could it be that many respondents simply hit the middle option on a question that sounded vague to them?

The younger generation might be less supportive of democracy, compared to their older peers. 38 percent of those between 18 and 35 years old agreed with the statement “democracy is preferable to any kind of government” compared to 42 percent in the 36-55 age cohort and 47 percent of those 56 and older.

Despite low trust and skepticism towards the governance structures, the young generation believes things in Armenia will improve.

The World Values Survey helps us see the misconceptions Armenians have about democracy. When asked what constitutes an essential characteristic of democracy, 75 percent of respondents in 2011 thought that state aid for unemployment is such an essential characteristic; another 67 percent thought that democracy means government taxing the rich and subsidizing the poor; 45 percent believed that democracy is when the state makes people’s incomes equal (another flashback from socialism, perhaps). These misconceptions are not related to age. The young generation is as likely to express these opinions as older people. Armenians often confuse democracy with social welfare.

Caucasus Barometer suggests that the younger generation might be less supportive of democracy, compared to their older peers. 38 percent of those between 18 and 35 years old agreed with the statement “democracy is preferable to any kind of government” compared to 42 percent in the 36-55 age cohort and 47 percent of those 56 and older.

Taken together, the data of the Independence Generation Study, the World Values Survey and the Caucasus Barometer suggest that the Armenian youth pays lip service to democracy, without a clear understanding of what it is and without a firm commitment to it. What they express is not a genuine satisfaction with democracy, but probably a general “it’s ok” kind of an attitude, colored by the optimism of youth and a belief in a better future. This is the overall good news of the study: despite low trust and skepticism towards the governance structures, the young generation believes things in Armenia will improve. Without such optimism, our future would look bleak indeed.

Recommendations

The study shows misperceptions and confused ideas about democracy, liberalism, capitalism and so on. My recommendation is not more training and awareness raising campaigns. If it did not work for the past two decades, there is little reason to believe it will work now. As an educator who works with the young people and invites them to grapple with those very questions of ideology, forms of government, good and bad aspects of democracy and its practical daily implications, my recommendation is to encourage the natural curiosity of the young minds. Don’t give them ready-made answers. Make them ask questions. What are their values? What do they believe in? What do they want for themselves, their families and their country? At a time when the world is questioning the Washington consensus and the dominance of the neo-liberal paradigm, it is naïve to expect the Armenian youth to embrace those values. Instead, they are searching for their own answers. That should be encouraged. Support for critical thinking through various forms of education is most likely the best, though not the shortest, neither the most obvious (in terms of measurable impact) type of action needed.