In 2011, four citizens of the Republic of Armenia were called up for mandatory military service. The men – Artur Adyan, Garegin Avetisyan, Harutyun Khachatryan and Vahagn Margaryan – refused to comply stating it was against their religious beliefs. The men are Jehovah’s Witnesses. Additionally, they also refused alternative service which is envisioned under Armenian law stating that it did not comply with European standards, which guarantee that military authorities are excluded from the process and service is of civilian nature. If the men had opted for alternative service, they would have to serve for 3.5 years as opposed to the regular two-year mandatory service. The four applicants stressed their readiness to perform alternative labor service if it was not supervised by military authorities and did not violate their religious beliefs.

In the autumn of that same year, the four men were convicted of draft evasion. They were sentenced to two years and six months in prison. All four men served for just over two years before being released in October 2013 in a general amnesty. After exhausting all legal means, the four men filed cases against Armenia at the European Court of Human Rights (Application no. 75604/11). Just recently, on October 12, 2017, the ECtHR declared that in fact, there had been a violation of Article 9 of the Convention and delivered a judgment according to which the Armenian government has to pay EUR 12,000 compensation to each applicant.

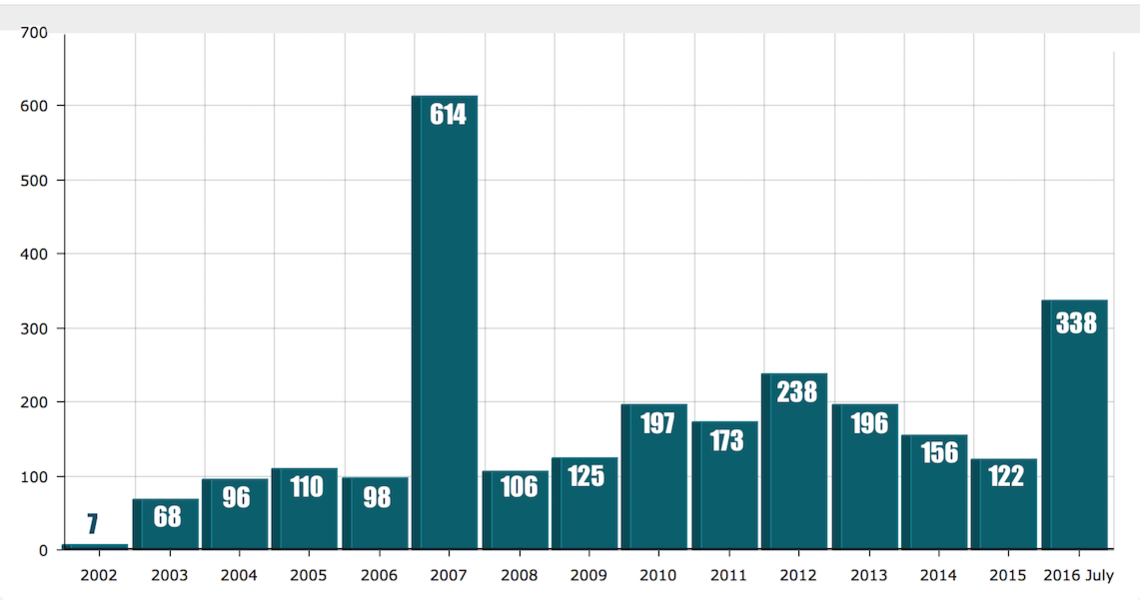

Since joining the Council of Europe on January 25, 2001, becoming its 42nd member state and ratifying the European Convention on Human Rights (2002), Armenia’s government has been obligated to pay over 900,000 Euros as compensation to Armenian nationals who have taken their cases against the Republic of Armenia to the ECtHR. Today, per capita, Armenia has one of the highest numbers of complaints at the ECtHR.

As of 2016, 1,406 out of 3,060 applications were declared inadmissible or struck out during the Court’s initial procedure of pending out application admissibility. Vahe Grigoryan, a Legal Consultant at the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre in the UK, emphasizes that the main generator of the flow of complaints to the Court is the result of systemic defects within the Armenian judiciary. To date, the court has delivered 85 judgments against Armenia

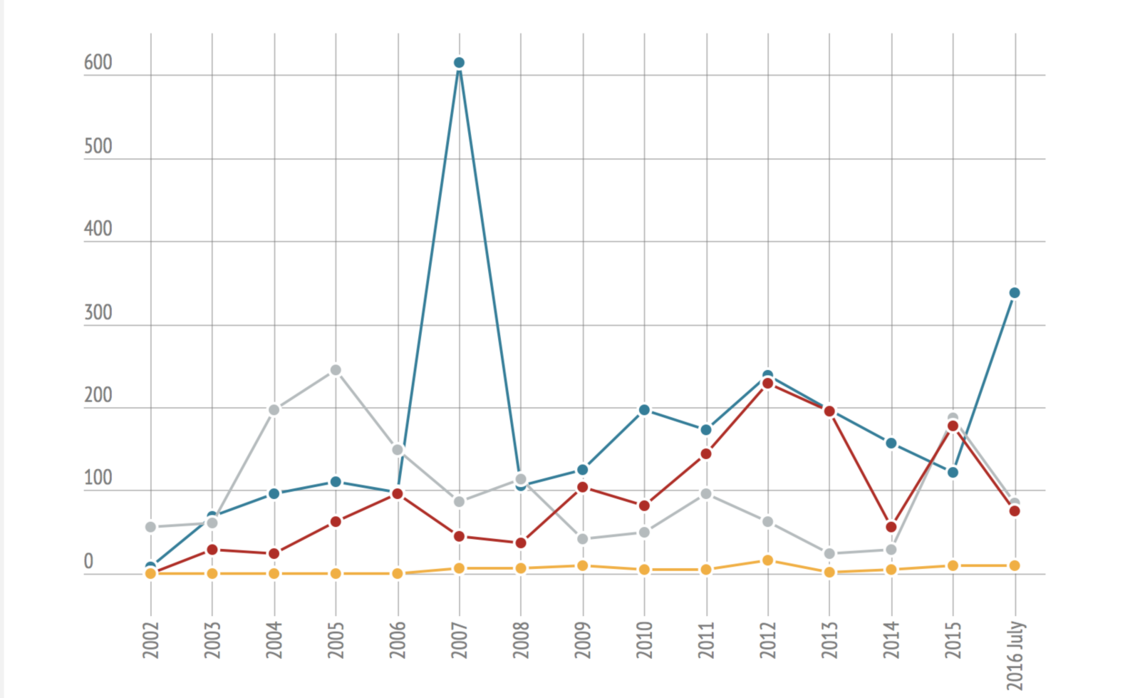

Blue- applications allocated / Grey-applications decided / Red- applications declared inadmissible or struck out / Yellow- applications decided by judgment. Source

Today, per capita, Armenia has one of the highest numbers of complaints at the ECtHR. The government has been obligated to pay over 900,000 Euros in compensation in rulings against the Republic of Armenia.

The ECtHR has specific admissibility criteria, which are strictly followed when the applications are received. In order to be considered admissible the applications submitted by individuals should comply with the following conditions:

– all domestic remedies should have been exhausted before applying to the Court;

– the application should be introduced within the period of 6 months after the final decision was made on national level;

– the application should not be substantially the same as a matter already examined by the Court;

– the applicant is not eligible to apply if he/she has also applied to another international investigation or settlement;

– the complaint should be made against a state, which ratified the European Convention;

– the application will be considered inadmissible if it is ill-founded or contains an abuse of the right of individual application to the Court;

– the application will be inadmissible if the applicant has not suffered a significant disadvantage.

Based on ECtHR statistics, the countries with the highest number of applications are Ukraine, Turkey, Russia, and Italy, respectively. Currently, Ukraine has the most applications pending before the Court; one case for every 9,125 persons. In Turkey and Italy the numbers are relatively the same: 18,572 and 18,831 respectively; and the numbers for Armenia and Russia are again relatively close: 39,000 and 42,528, respectively.

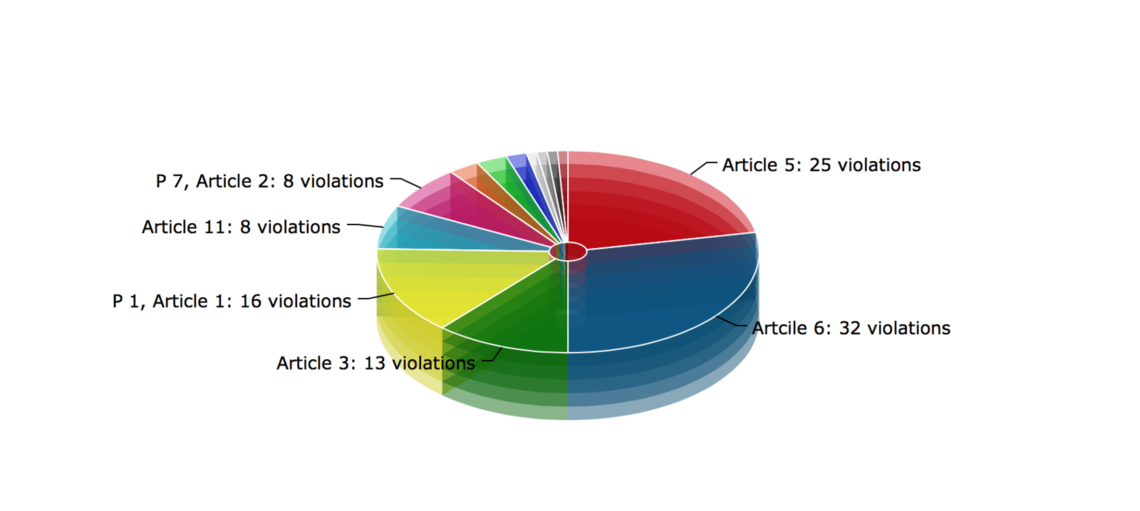

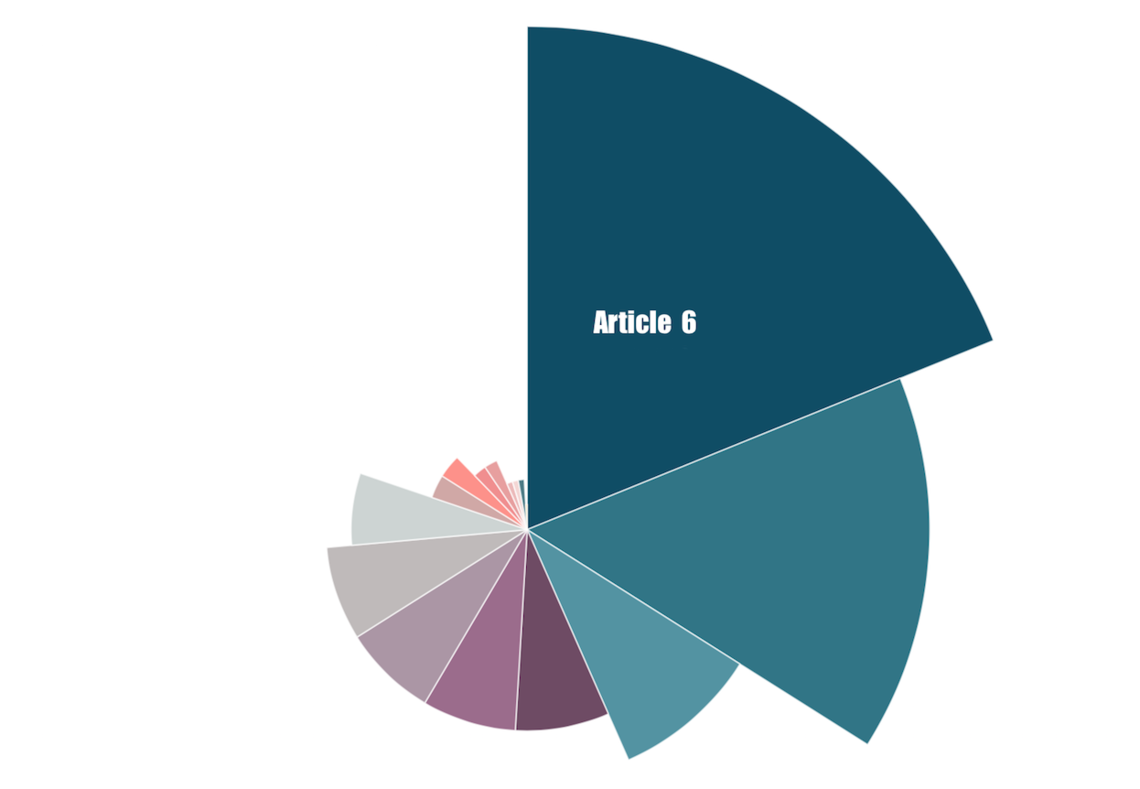

In the cases against Armenia from 2002-2016, the main articles of the Convention which were violated include: the right to a fair trial (37 cases), right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions (property rights, 24 cases), right to liberty (16 cases), prohibition of torture (11 cases), freedom of assembly (eight cases), freedom of religion (four cases), right to life (three cases), right to respect for private and family life (two cases), right to an effective remedy (four cases), and prohibition of discrimination (one case). Out of these 10 articles, right to a fair trial (Article 6) is the one which was violated the most: 32 times out of 75.

Virabyan v. Armenia

Virabyan v. Armenia (Application no. 40094/05) is a high profile case against Armenia, which concerns the torture of an opposition activist while in police custody in April 2004. During the 2003 presidential elections, Virabyan acted as a proxy for the main opposition candidate. According to police materials, on April 23, 2004, at 5:40 p.m. on suspicion of carrying a firearm and for using foul language towards police officers and not obeying their lawful orders, Virabyan was taken to the Artashat police station. The applicant claimed that he was repeatedly kicked and punched in the groin during his custody and, as a result, his left testicle had to be removed. There were violations of Article 3, prohibition of torture and lack of an effective investigation, of Article 6 & 2, the presumption of innocence, and of Article 14, prohibition of discrimination. This is the first case in which the Court found a violation of Article 3 by Armenia on account of an applicant having been tortured. The Court also criticized the Armenian authorities for failing to conduct an effective investigation into Virabyan’s allegations that his ill-treatment had been politically motivated.

Aside from the cases brought to the Court by Armenian nationals, another reason for the high number of applications against the government stems from the Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh) Conflict, which counts for approximately ⅓ of the pending cases.

Chiragov and Others v. Armenia

One of the noteworthy cases against Armenia, the compensation claim of which is still pending is Chiragov and Others v. Armenia (Application no.13216/05). This case may have significant influence (positive or negative) on Armenian-Azerbaijani relations as it concerns one of the most sensitive aspects of the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) conflict: the return of refugees and IDPs and/or remedies for their damages and losses. The applicants who identify themselves as Azerbaijani Kurds claimed that they lived in the district of Lachin for their entire life (de jure recognized as part of Azerbaijan, but currently de facto controlled by Artsakh). The applicants alleged that since 1992, when the Artsakh Conflict gradually escalated into a full-scale war, they were forced to leave their properties and were prohibited from returning to their homes by Armenian forces. The applicants claimed that a number of rights under the Convention were violated by Armenia.

Violations by Subject Matter (2002-2016)

As statistics in the official website of the Government’s representation before the ECtHR state, the complaints of Article 6, right to a fair trial, surpasses all the other complaints within the pool of applications against Armenia, as is the case for all the other ECHR member states. Source

The Court has granted the complaints of the applicants by finding that Armenia was in breach of the following rights of the Convention:

– the right to respect for applicants’ home regarding the continuous denial of access to it (Article 8 of the Convention);

– the right to applicants’ property regarding the denial of access to it and lack of compensation (Article 1 of Protocol of the Convention);

– the right to effective remedies, which were not available to the applicants in respect of their above-mentioned complaints (Article 13 of the Convention).

Statistics provided on the website of the Government’s Representation Before the ECtHR state that as a result of the 75 delivered judgments against Armenia, the Government paid 903,229 EUR (504,161,390 AMD) as compensation to all the Armenian nationals whose rights have been violated by a government agency or its officials.

Grigoryan identifies three main reasons for the high number of applications against Armenia pending before the Court. He stresses that the core of the systemic problems in the judiciary is the lack of its independence, which incubates violations of various rights under the Convention. “If the judiciary lacks basic independence in adjudicating disputes between the parties, then anything else but justice can be the possible outcome of the proceedings,” says Grigoryan.

International observers, including the United Nations Human Rights Council, Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and International Federation for Human Rights have all criticized the Armenian judiciary’s shortcomings in this regard. Grigoryan notes that this is a systemic defect that stems from deliberate policies and practices of the political elite aimed at subjugating the judiciary. The result of those policies and practices, of course, could not have happened without “the silent obedience of the judges.”

The system of the appointment and promotion of judges in Armenia, included in the Constitutional amendments of 2005, provided unlimited power to the country’s President to appoint judges, to promote them and, more importantly, to grant leave to prosecute a judge. This situation severely restricts the independence of the judiciary which has no room to exercise discretion to act against the interests of the political elite. “As a result, Armenia is a rare nation in the world that despite not being a monarchy, has a judiciary where all the appointments of the judges are made by the President, by his unlimited discretion,” adds Grigoryan.

The injustice which is a direct result of the dysfunction of the judiciary and lack of its independence consequently affects the quality of justice in Armenia. Grigoryan believes that the unrestricted and unlimited influence and interference by political powers, including the President of Armenia has hampered the work of the courts. “The Court of Cassation and, more specifically, the President of the Court of Cassation are the primary tools which are employed to control the courts and judges for this purpose,” Grigoryan explains. He further stresses that such unrestricted interference over the judiciary has its institutional and subjective reasons.

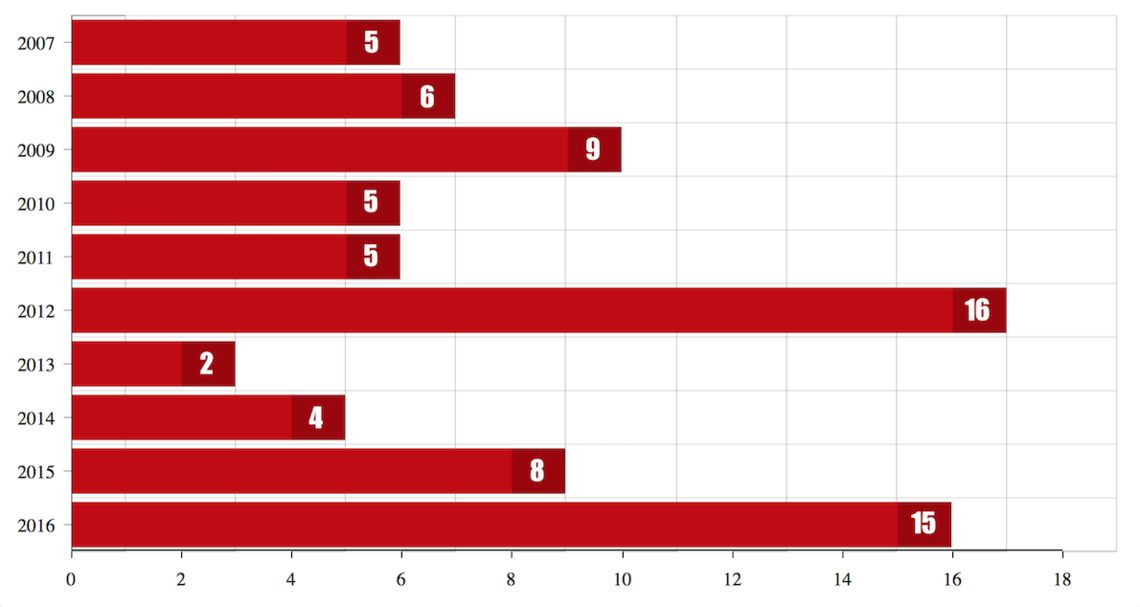

Violations by Cases (2002-2016). Source

The current situation is the result of the influence of political elites to exercise unrestricted power in order to control the judiciary on the one hand, and lack of culture and judicial tradition of genuine independence of the judiciary, on the other. As a result, the judicial system of Armenia continuously fails to guarantee the transparency of the system and increase citizens’ trust towards it. Thus, it is composed of and operates under the overall control of the current President and ruling Republican Party of Armenia. Grigoryan clarifies that in such circumstances, the judiciary does not need any instruction from a “supervising authority,” rather operates for the protection of the interests of that political group.

According to Grigoryan, another reason that Armenia has one of the highest numbers of complaints per population in the ECtHR is the backlog of cases against Armenia that has grown over the last 13 years, since the country’s accession to the ECHR.

Since 2003, when an Armenian judge was first elected to the ECtHR, the country had one of the slowest processing speeds of cases. Former Armenian judge, Alvina Gyulumyan, who was in office throughout this period, publicly stated that the primary reasons of non-performance were understaffing and long vacation period of the Armenian lawyer in the ECtHR.

The European Court, with the magnitude and scale of examining a high volume of cases from 47 jurisdictions in one judicial institution, as well as the quality of justice it renders on a daily basis, it certainly faces difficulties. Grigoryan believes that it is unimaginable that the reason for the overall low speed of processing Armenian cases can be trivialized and explained by a long-term vacation of a Council of Europe employee, who enjoyed his or her legal leave. “Even if that was indeed the technical reason, we are not speaking about unexpected snowfall in the middle of July. If he/she was entitled to leave, that could have been foreseen long before,” he adds.

As statistics in the official website of the Government’s representation before the ECtHR state, the complaints of Article 6, right to a fair trial, surpasses all the other complaints within the pool of applications against Armenia, as is the case for all the other ECHR member states. Grigoryan explains that the most obvious reason for the violations is that the exercise of the right to a fair trial is an important precondition for the protection of a number of other rights. Thus, if a fair trial is not secured, the vast majority of the Convention rights are exposed to arbitrariness and grotesque failure of protection. Therefore, it is not uncommon that a complaint of a substantive right may arrive at the European Court along with a complaint of a violation of Article 6.

“When speaking about the right to a fair trial, we speak about a large number of parallel and often distinct rights, which all are prescribed by Article 6, under the heading of the right to a fair trial,” notes Grigoryan. “There are more than a dozen distinct procedural rights that are involved in criminal, civil, administrative, disciplinary proceedings or those before the constitutional courts.”

While talking about the possible solutions of the problem in Armenia, Grigoryan stressed the importance of building the rule of law: “I cannot recall any example in history when a rule of law nation existed without a functioning democracy.” He further stresses that the right to a fair trial has a twofold purpose. On an individual level, it secures fairness of the judicial review as well as the protection of individual rights. On a collective level, it is the guardian of democracy and the rule of law. “It would be unreasonable to try to secure the right to a fair trial in an environment where the overall tendency of processes leads to the opposite direction,” Grigoryan says.