Opposition parties in Armenia’s second and third largest cities considered the last local municipal elections to be illegitimate and refused to attend council meetings for a year. Gyumri and Vanadzor held their most-recent municipal elections on October 2, 2016. It was the first (and, to date, only) municipal election the cities have held under the new 2015 Constitution and updated Electoral Code, under which the mayor would no longer be directly-elected but would instead be chosen by the city council.[1] Thus, they would be following the model used in Yerevan since 2009. In turn, seats on the city council would be allocated to parties based on the proportion of votes they received.[2] That principle is a fair one. It was the additional tweaks that threw things off course.

Gyumri Results

In Gyumri, Samvel Balasanyan was the incumbent mayor, seeking re-election in 2016. Previously a manager at a local beer brewery, he was first elected to the Armenian parliament in 1999 as an independent candidate in a district seat. Over his 13 years in parliament, he changed his political affiliation several times, starting off as a member of the Stability caucus, then joining the People’s Agricultural and Industrial Union, until he joined the Country of Law Party and became their caucus leader, finally joining the Prosperous Armenia Party (PAP), which he represented as Deputy Speaker of the National Assembly. He left national politics to run for Mayor of Gyumri in 2012 under the PAP banner, winning with 65% support (exactly 27,500 votes). In 2015, when PAP founder Gagik Tsarukyan announced that he would be stepping down from active politics (he later re-entered in 2017), Balasanyan left the PAP and continued serving Gyumri as mayor as an independent. For his re-election campaign in 2016, as the new rules required the mayor to secure council support, Balasanyan ran as the mayoral candidate of the “Balasanyan Alliance,” which included the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) and the smaller Christian Democratic Union of Armenia.

Lining up to challenge him, a group of employees at the privately-owned GALA television station, which broadcasts from Gyumri and was often critical of Serzh Sargsyan’s RPA government of the time, created a new political party to contest the Gyumri municipal election. The party was named “Alliance of Like-Minded Liberals,” which is abbreviated to GALA in Armenian. Levon Barseghyan, an incumbent city councillor first elected in 2012 and founding editor of Gyumri’s Asparez newspaper, joined the GALA ticket. The Bright Armenia Party (BAP) made an agreement to run a joint party list with the GALA Party in Gyumri. Three of the 24 candidates on the list were nominated by the BAP, but they would campaign together under the GALA banner.

Abandoned by Balasanyan, the Prosperous Armenia Party was now campaigning against their former colleague. Their new mayoral candidate was Vardevan Grigoryan. Sadly, tragedy struck his family with weeks to go before the vote. His son, in his mid-20s, suffered a fatal gunshot wound in the basement of their home. Police determined it to be a suicide but the timing of the incident did have some people exploring conspiracy theories. All parties suspended their campaigning activities in the aftermath of the event to show respect. Media reports paid particular attention to a poster of gambling dice that had been put up in the vicinity of the Grigoryan home then quickly taken down. The candidate’s brother had been killed two years earlier.

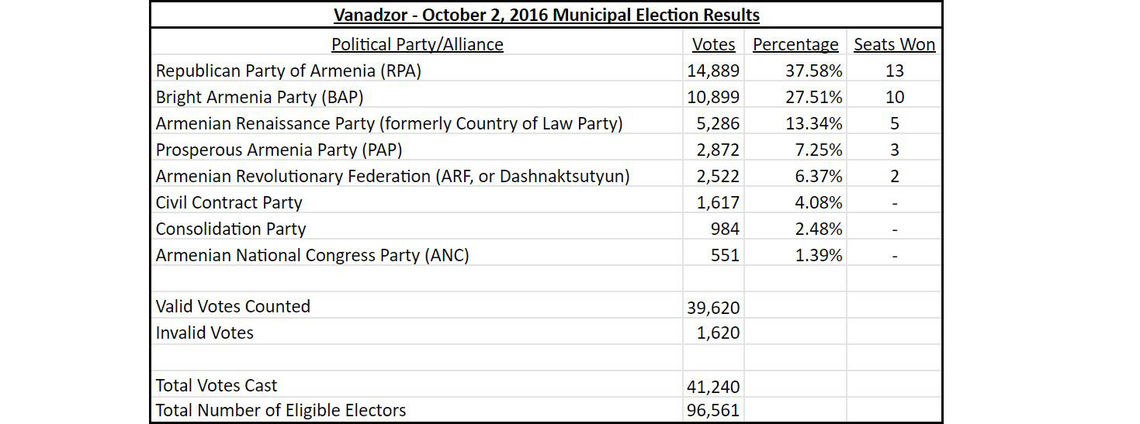

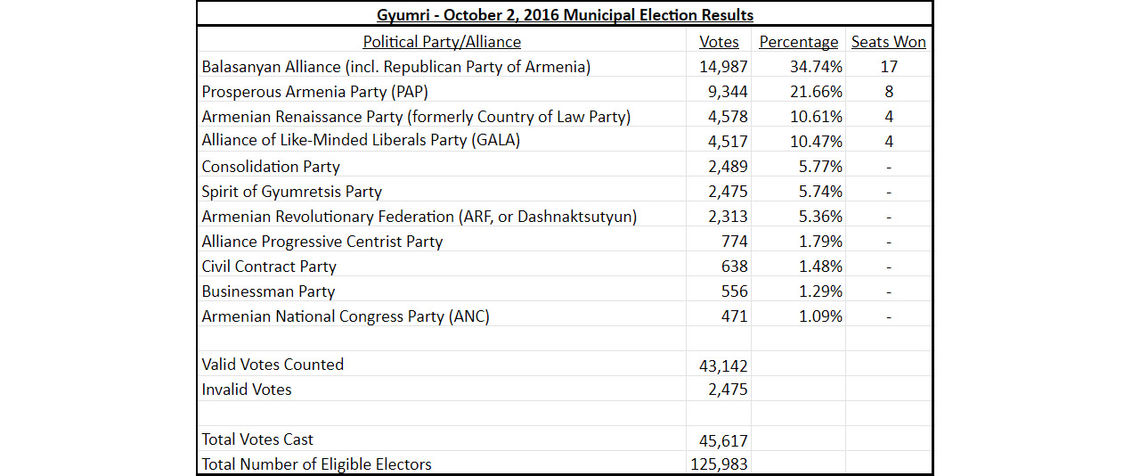

On election night, the following were the final results:

Source: Central Election Commission

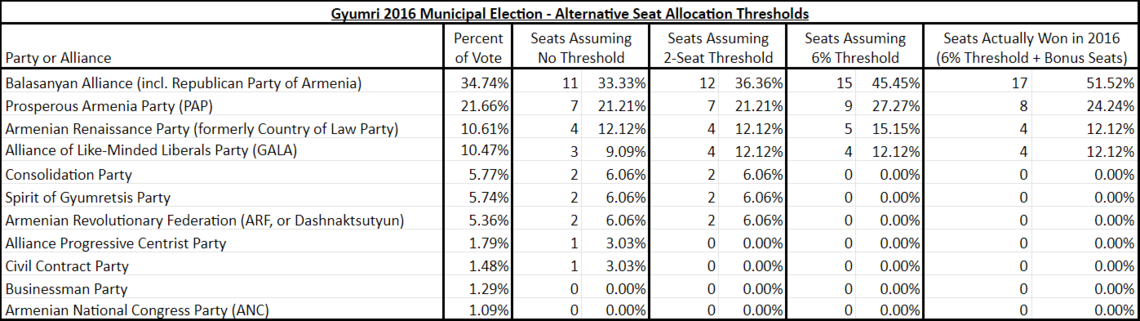

Instead of a hard percentage-based cutoff, a different approach could be to, first, consider all party vote totals in allocating seats, then, redo the calculation by considering only those parties or alliances that received at least two seats. The table above provides the results that a 2-seat threshold would yield, which are much more proportional than the way the seats were actually finally allocated.

Recommendation: Instead of 6% and 8% thresholds for parties and party alliances, use a 2-seat minimum threshold, applied equally to both parties and party alliances. Also, require that the top two candidates on a party (or alliance) list be from different genders.

Problem #2: Bonus Seats Grant Artificial Majority

In the table above, you probably noticed that the 6% threshold was not the only factor distorting the parties’ seat counts from their corresponding vote totals. When Serzh Sargsyan’s Republican Party rewrote the Armenian Constitution and Electoral Code, they placed special emphasis on a “stable majority” principle, where the largest party received major advantages to minimize the chances that they would need to cooperate with other parties in making decisions. At the municipal level, this included a “bonus seat” clause that automatically gave a majority of the seats to the largest party, if they would otherwise have between 40-50% of the seats.[5] In Gyumri, after the 6% threshold is applied, the Balasanyan Alliance would have had 15 seats (45.5% of the total – 33). Thus, the bonus seat provision kicked in, giving them an extra two seats (taking them from the opposition parties) so that they would have a majority. You can see how the layers of distortions advantaged the establishment: they received 34.7% of the vote, qualifying them for 45.5% of the initial seat allocation, knocking them up to a 51.5% majority, granting them 100% of the decision-making power.

The concept of bonus seats has a suspicious history. It was first used by Benito Mussolini [6] to take control of the Italian Parliament in 1924 (and subsequently cancel multi-party elections). Various other bonus schemes were introduced and eliminated in Italy’s post-war history, until the practice was struck down by their constitutional court in 2013.

Greece is another country that used bonus seats in national elections. The largest party would get 50 additional seats in parliament, which did not guarantee a majority but gave them a significant advantage. They eliminated the practice by a vote in parliament in 2016.

Stable majorities provide a government with the legal cover to make unpopular decisions like privatizing assets, negotiating harshly with public sector unions, expropriating land or creating new taxes. They have a big impact under Armenia’s current Electoral Code as the mayors of Yerevan, Gyumri and Vanadzor need to be elected by an absolute majority of all city councillors. Currently, there is a provision to hold a runoff election between the top two candidates if no mayoral candidate receives majority support from the city council in the first round.

Without a majority, a mayor would have to depend on other parties, either as part of a coalition agreement or on an ad-hoc basis, to pass by-laws and, most crucially, the budget. A politician may view this as cumbersome and restricting their flexibility. In a truly democratic process, however, a government that never received a majority of the votes in the first place should be made to negotiate with others to find mutually acceptable solutions.

Currently, only the top two candidates for mayor would participate in a runoff. It would be more fair to hold multiple runoff rounds, with only the bottom candidate being eliminated in each round.

Recommendation: Eliminate bonus seats. Allow city council to vote for the mayor using multiple runoff rounds, if required, such that the final winner does not require an absolute majority of the entire council (in the case of abstentions).

Gyumri Boycott

Although these provisions are written into the Electoral Code, they infuriated the opposition. They appealed the results in court and refused to take part in city council sessions while the matter was still pending. In the meantime, the Balasanyan Alliance conducted their city council sessions with their 17-seat majority, passing all items unanimously. Eventually, the Constitutional Court upheld the constitutionality of the bonus seat provision, rejecting the appeal. By autumn 2017, all three opposition parties that did receive seats in the election had ended their boycott and begun participating in the city council sessions.

Vanadzor Results

In Vanadzor, five-term mayor Samvel Darbinyan, an RPA member, did not run for re-election in 2016. The RPA named Mamikon Aslanyan, a notary, as their mayoral candidate. The main challenger was the BAP, whose mayoral candidate was Krist Marukyan. His brother, Edmon Marukyan, had been elected to the National Assembly in 2012 to represent Vanadzor as an independent, later founding the Bright Armenia Party. The final results are shown below: