My name is Arthur Tonoyan. I am the Executive Director of the Armenian Psychoanalytic Association and work at the Ayg Psychological Services Center, the National Center for Mental Health, and the Nubarashen Psychiatric Hospital as a clinical psychologist.

I started my professional career in 2013. I worked as a child psychologist at Green Floor-Rainbow Garden, and as a clinical psychologist at the Nubarashen Correctional Institute, and the Yerevan-Kentron penitentiary.

The Four-Day War

I first came into contact with war during the 2016 Four Day April War. It was an unprecedented challenge. I started working with wounded soldiers to provide individual counseling and psychotherapy sessions.

At that time, a group of us decided to create a team that would be specially trained to provide psychological support in war and other disaster situations. We participated in survival courses, as the Ministry of Defense had reported that Armenia lacked the needed number of specialists with those skills in the event of an emergency.

We trained with the Special Forces. We gained a lot of experience, but that was the end of our “psychological career in war”. Professionals did not place enough importance on specializing in this field. Although I myself participated in all the seminars, I did not try to immerse myself too much in military psychology.

Surprise

On September 27, 2020, on that painful day when the war broke out, I was called to the military commissariat to be sent to the border. I waited there until midnight, but they did not take me. They told me to go home and said that I might be called back later.

The thought of going to the border would not leave me. Several times I attempted to travel to Vardenis with the director of the Ayg Psychological Services Center, but both attempts failed. My two colleagues and I had already packed our bags and were prepared to go there and work, but another team went instead of us.

The psychological unit ramped up very quickly. It was organized by Armen Soghoyan (psychiatrist, President of the Psychiatric Association), Khachik Gasparyan (clinical psychologist) and others. They were well organized and were able to promptly gather a group of specialists and divide the work.

The night when my trip to Vardenis was called off, I had a chance encounter with Armen and told him that I wanted to go to the front line. Later, I was informed that we would leave for Goris early in the morning. My things were already packed, and I was happy, as I had already been denied going to the border three times during this war.

My family members started jokingly saying, “Return to sender… Whoever takes you, does not keep you.” I repeatedly bid farewell to my friends, only to later tell them that I did not go.

At 6 a.m., I received a call from the commissariat to report in person again. Again, it turned out that there was not a seat for me in the vehicle. I said, “I will not go back home. If you do not take me, I will sit on the hood of the car and travel like that.” Finally, I managed to insist on going with my own car, accompanied by another psychologist, Aram, who is a specialist in cognitive therapy. We were told that we were going to work in the hospital in Goris, and afterwards in Stepanakert. We had prepared accordingly. I was wearing a white T-shirt and blue pants. I even took a lab coat.

When we arrived in Goris, I was told to leave my car behind. We sat in a military jeep and set off. After about 20-30 minutes, I wasn’t sure where we were. I asked Aram, “Where are we going?” Surprised, he said, “Maybe we are going to the battlefield.”

As we approached Jrakan, we met large groups of people who were leaving their weapons and retreating, signaling to us not to go there, that it is a “meat grinder”.

Ministry of Defense representatives told us to stay in the car until they could figure out what was happening by speaking to those turning back. It was like a scene from the movies. There was tremendous panic. I did not understand what was happening; I had no idea that the situation was so complicated and catastrophic.

We eventually moved on and came to a place where there were a large number of troops. It was an unexpected scene for me: a lot of chaos, everyone was shouting, looking for something. They told us, “We’ve arrived. Go out there and work.”

Up until that moment, I thought I would be working in a hospital with the wounded. But this was real field work.

I got out of the car in my white shirt, with white sneakers and ironed pants. The other psychologist, Aram, had long curly hair with a mustache like that of Salvador Dali. We met the troops who had been living the war, had not had a chance to wash for days, had gone without meals and slept in open fields. We were from two different realities.

At that moment, I thought I should quickly try to minimize the contrast. I changed my sneakers with another pair I had on me. I took my military backpack and walked toward the army.

“Hi guys, how are you? Can we have some coffee?”

That was the first and last coffee I drank during the war.

Adapting

I started talking to the men, trying to understand what issues they had.

They were very surprised and looked at me strangely: “But what will you be able to do?” They seemed to wonder, “Where have you come from, so cleanly dressed and with neatly combed hair?” I tried to explain that I will also be looking like them before long.

At first, we were traveling to different locations. Then, out of the blue, we found ourselves close to the front line. We had to work with soldiers and volunteers deployed to the front.

If you have never yourself been on the front lines of war, how can you work with those whom you are supposed to prepare for it? But that is psychology for you: the psychologist does not have to be in the same situation to be able to help. They must understand the given individual in the given moment.

In the beginning, I did not know that we were so close to the front line. It began to rain heavily during the night; the sky started to turn red and explosions were heard. I said, “Lightning struck. One, two…” Aram replied, “Arthur, don’t you want to accept that it is not lightning? It is a heavy weapon, a rocket that is exploding.” The sky was completely red, everything was shaking. And yet I was saying, “Oh, lightning struck again.”

Denying the existence of the explosion was my internal defense mechanism. There was no electricity. We were already in our dugout, hungry and with no place to sleep. The three of us settled into a military jeep, which we had hid under the trees and covered up with bushes. At dawn, the shootings resumed. Even under these circumstances, I found spring water, and the first thing I did was brush my teeth. With projectiles exploding around me, I was standing there, brushing my teeth. It was amusing; it seemed like I was taking the situation lightly or that it was not sinking in. Yet, it was my way of overcoming my inner anxieties.

The first night, when I was very hungry, they opened a can of beans. I ate that bean stew as if it were the tastiest thing in the world.

We woke up at dawn and set off, because we were traveling constantly and changed locations as needed.

I was the only one with a computer. As it turned out, it would come in handy in locations where secret information had to be delivered, where there was no connection and no equipment. The guys would say, “It has become a historic computer that has seen war.”

Panic

Panic was abundant.

We toiled night and day. We were trying to help everybody, but it was evident that we would be unable to get to everyone.

We did both individual and group sessions. But the latter was a different kind of psychological effort. It included everyone: officers, doctors, soldiers. The issues were also varied: one had a psychotic reaction, the other neurosis, the next mutism, and so on.

The two instincts of our psyche, life and death, often come into conflict in such situations. Instincts help us survive: you do everything you can to stay alive. The other is pathology: when the fear response does not function, as was my case.

When the shooting started again and someone was injured, I realized then and there that I was not reacting to fear. With my computer over my shoulder, I ran without a minute’s thought given to the fact that I had no bulletproof vest or something to shield me, and I could be the next to get shot. I ran and saw a fallen major. I studied for two years to get into medical school, but then I chose another profession. I know biology, and the survival training I received in 2016 helped me during those days. I do not know how, but at that moment, everything came back to me. I bandaged his intestines, because his body had been lacerated in seven places and he was unconscious. There were no actual bandages, though; I ripped a shirt for its material. Suddenly, a car carrying medication appeared. I dumped the medicine out to find what I needed. Everyone was confused, did not know what to do, and they would call out to me, “Doctor, doctor.” At that moment, I had involuntarily become a doctor. I bandaged one person and turned to examine the other. Unfortunately, he was already dead; I could not do anything for him.

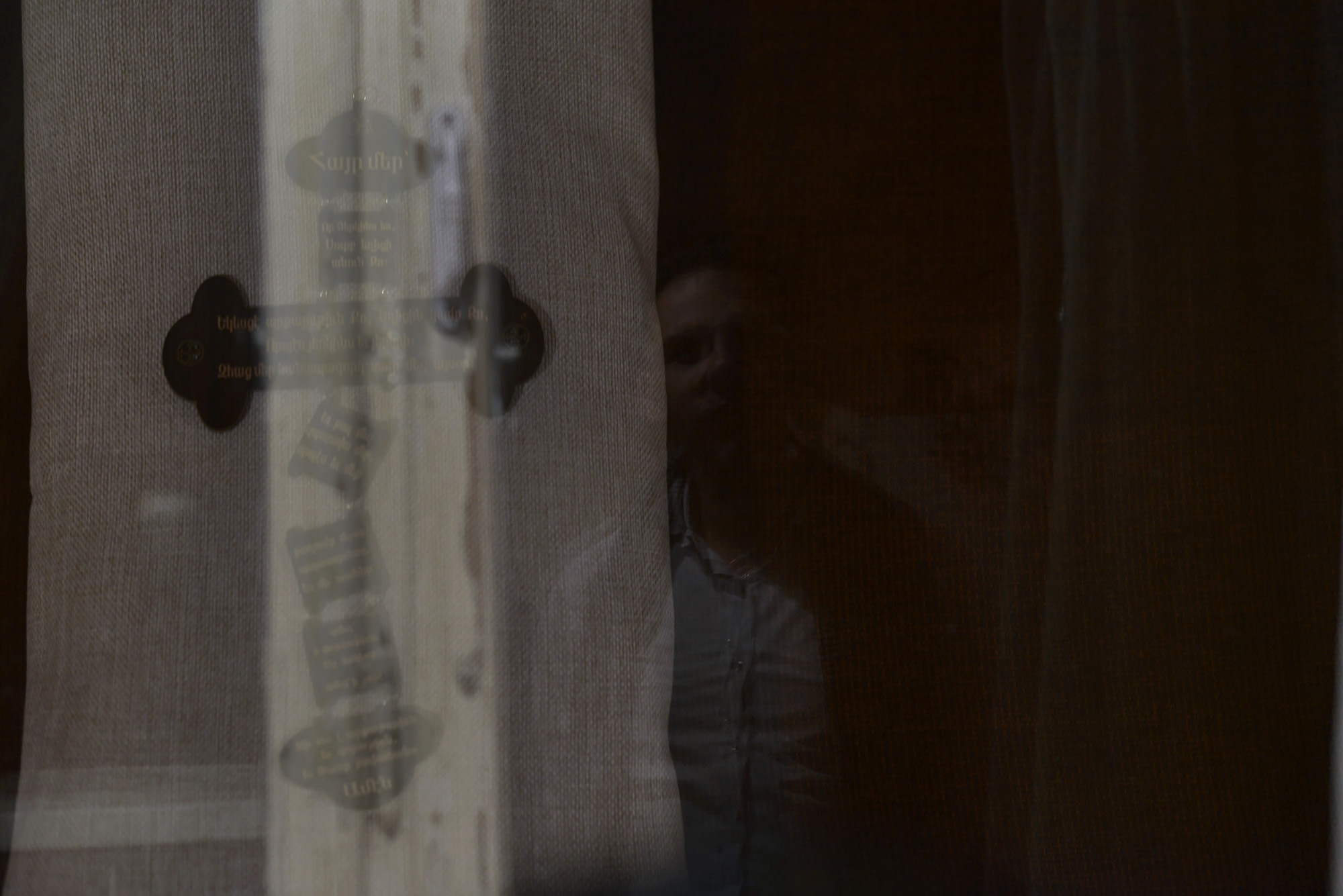

We, the psychologists, decided not to wear a military uniform; we did not have bulletproof vests, we did not have any military items. That was our principle. It aided our work. Sometimes a soldier would approach us, hug us and say, “Let me embrace you. I do not know when I will see someone in civilian clothes again.”

Later on, the soldiers began to receive us with more ease. They often came to us and asked, “Can I talk to you?” Sometimes they cried and got emotional.

Many times, when alone, I would get emotional myself. I watched groups ascend the mountain before me, and realized that few returned.

Dark Humor

Humor was a way of overcoming fear, depression and fatigue. We were very tired at the end of the day. One day, the troops had just left, and we were in a house. It was raining heavily, there was no electricity, and Aram and I were sitting inside. We thought of playing Rock Paper Scissors to pass the time. Then someone shouted, “They switched on the electricity!” Excitedly, we started looking for the source of electricity in the house. We found it, but could not turn the lights on, because it was dangerous; the enemy might see us. So we just charged our equipment and had a hot drink.

Two thick cables ran down the wall, and there was a large electric heater with two open wires. The cables had to be connected to the open wires. I am afraid of electricity. I am a psychoanalyst, Aram is a cognitive therapist. So I said, “Aram, I am analytical. I can analyze what we can do. You are a behavioral specialist; you have to do this job. I think it, you do it.”

“But why should I die?” he asks.

“Because according to theories, I cannot connect it; I am ‘the brain’ and you are ‘the behavior’,” I answered.

Aram made the first attempt at connecting the wires and they short-circuited. I continued to joke, “Aram, you should not be afraid. You should overcome your fears, because we want to drink hot coffee.” Aram tried once more and succeeded. We made our coffee. With our phones charged, for a long time, we looked around to search for a place where the house owners might have kept the WiFi code. We had just found it and successfully connected to the WiFi when soldiers burst in and said “We are quickly leaving here.”

We hesitated, “But guys, the coffee is finally ready, the WiFi is working, everything is ready, let’s sit down for a bit.” The soldiers made it clear that the enemy was gaining on us. We had no choice but to leave quickly.

Our team included Vigen Manukyan, Hakob Govorgyan, Alik Babayan, the leader of our group, and our driver Vardan—a.k.a Schumacher. He drove the jeep as if he were driving a Porsche. He was an exceptional driver and human being. He drove in the dark without turning on the headlights. He would not let you be sad; he kept talking to keep you occupied, so you didn’t have time to feel sad.

Goris

We finally arrived in Goris. We had received orders to work in the Goris regiment. We would make rounds at the border and on the front line simultaneously. One day, after we had left our station, it was bombed shortly after, killing eight people.

There were 600 people in the Goris regiment. We worked with groups who did not want to go to the front lines. A medical commission had been established. There was a medical center, there was a nurse, but there was no doctor. All the doctors were on the front line. I had become a doctor by force of circumstances; I was bandaging, injecting, etc.

I am thankful to all my doctor friends, because while located in Yerevan, they were always with me. I would call a traumatologist or a psychiatrist or a neurologist and describe the problem. I had some medical knowledge, but I am not a doctor. I would describe the situation, the pain, the patient would talk on the phone, and my doctor friends would tell me what to do.

There was also a young man there. He was the definition of a great man, in every sense of the word. He had come to serve, to go to war, but they did not take him because of a health issue. Throughout the entire war, he remained in Goris and took on the role of a feldsher*. He would pay for medicines from his own pocket. He felt guilty for not being on the front and, instead, he worked day and night. “I cannot sleep,” he would say. The entire medical unit was on his shoulders.

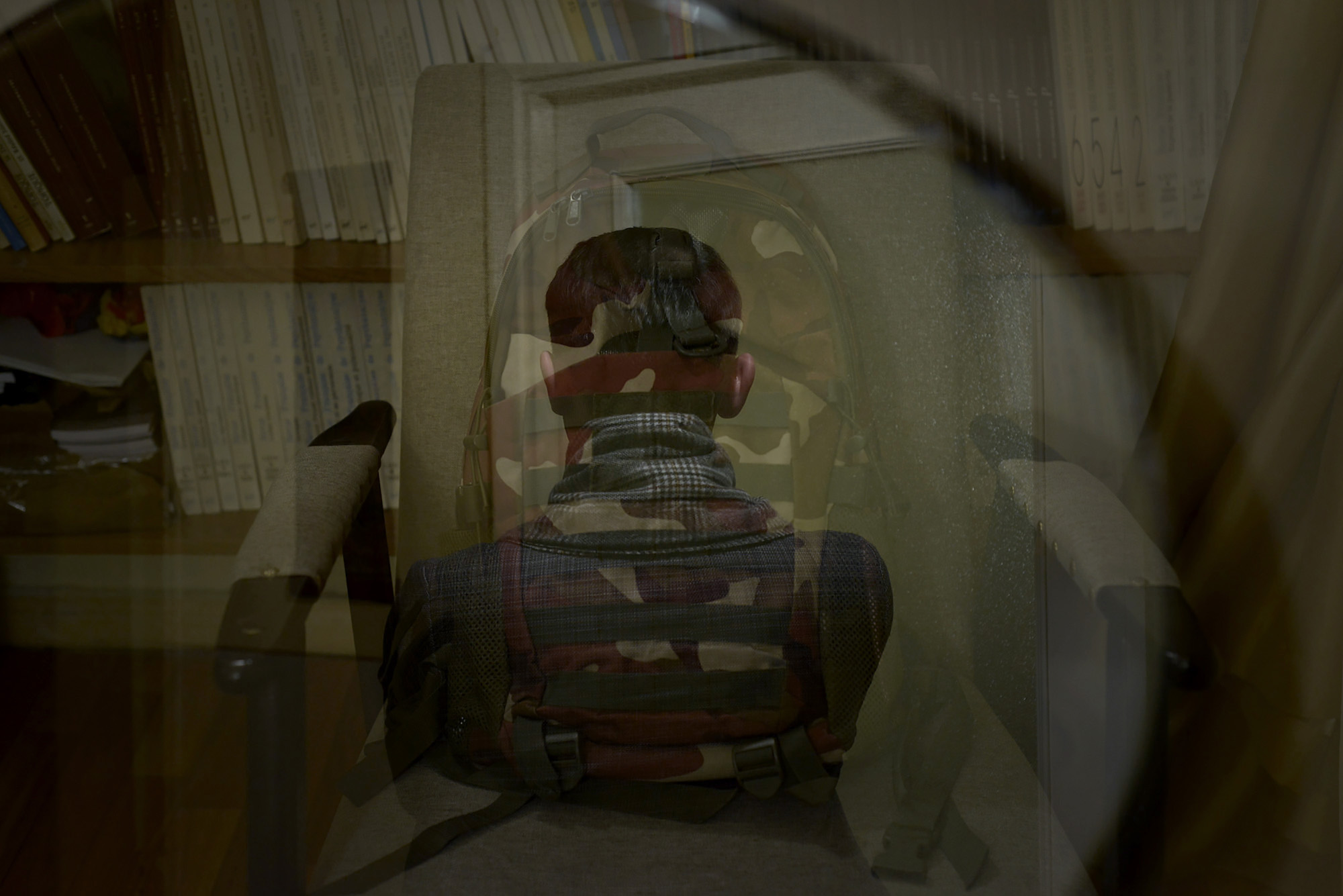

Khndzoresk

Khndzoresk became the first triage hospital; the most severe cases were brought here. At this point, the military hospital of Jrakan was no longer functional. It was an unbearable sight; everyone was crying out. It was an intense situation. I cannot describe what was happening there. I was admitting 30 patients a day in Khndzoresk, because of which, at one point, I felt like my sensory system was failing me. There was a patient who was in psychosis. He would shout and beg me to sit next to him. He would hold my hand and say, “Do not leave me, I want to sleep for 10 minutes,” because he had not slept for five days. I held his hand. He would sleep, then scream again and embrace me. We sent such cases to Yerevan, to a psychiatric hospital.

I have never prescribed psychiatric drugs, because I am not a psychiatrist. I have not crossed the line of professional ethics. I would call my good colleague Lusine Arzumanyan, who is an excellent psychiatrist. I called other colleagues and described the problem. Sometimes, I passed the phone to the patient and a remote consultation was held. I myself did not diagnose. We cooperated with the doctors, the mental health department, and the heads of the Ministry of Defense. Assessing the soldier’s condition, I would guide them, indicating which soldier should be taken to a medical facility urgently, and who can continue to serve.

One of the most obvious psychological problems are the different situational reactions during the war. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is assessed after the war, i.e. at least 30 days needs to pass for PTSD to be diagnosed. But during the war, doctors can indicate that the individual has had a traumatic reaction. That is why we send them to a psychiatric hospital, where they are diagnosed.

Sisian

Then I returned to Sisian. By now, they were organizing things better; they were preparing the troops before sending them off. We started working with the troops.

There was a huge amount of work to be done in Sisian. I became a part-time taxi driver, taking soldiers to and from the hospital in my car. At the start of the war, when I came to Sisian, the situation was catastrophic: the hospital was full of burnt people, soldiers were lying on the ground with their names taped onto them so they would not get lost. Then a medical commission was set up to decide whether to send patients to Yerevan or not. One day, one of the doctors said, “You know what, my friend? Since we tend to the patients you bring, why don’t you come and tend to our patients.” This was because there was no psychologist there. And so we started cooperating. In the morning, I would take 15-30 people to them, and while my patients were being examined and tested, I would examine their patients and indicate who should be sent to Yerevan, who should stay, or what should be done. The hardest part was when the parents would beg, “Doctor, please! My child, my child, my child…” I was tired, I was powerless. I wanted to say, “I want to discharge everyone, but I cannot do that.” I had to keep my professional objectivity. I was not Artur anymore; I was a clinical psychologist and that was that.

I had taken the responsibility of working with a few patients. I did short therapy sessions with them, unlike field work, which requires other resources and experience.

There were cases when a soldier’s desire for revenge (for example, if someone dear to them had been wounded in front of their eyes) dulled his sense of awareness in the face of danger, and in ignoring that danger, he sacrificed his own life unnecessarily. In such cases, it was necessary to make sure they snapped out of that condition and directed their energy toward their mission.

Northern Avenue

We were in Kubatlu, but before we could reach the military barracks there, it was blown up. I found a notebook under the rubble: a soldier had written down memories and poems. I constantly think about finding the owner (if he is still alive), but I cannot part with that notebook yet.

We started working with the troops in Kubatlu. They were all magnificent young people. When they were feeling broken, and it was necessary to boost their energy and instill positive feelings, I would often say, “Guys, don’t be dispirited. We will meet up soon on Northern Avenue.”

In mid-November, when the war was over, I received a letter. “Good evening, are you well? I am sitting in the trench right now, and do you know what I just remembered? That we were still there: the war was ongoing and everything was fierce. We were not sure if we would live to see tomorrow or not, and you told one of the guys that we would get through it, that we would all survive and walk down Northern Avenue together. At that moment, I thought, ‘I wish this would come true.’ I did not believe that the day would come when I would walk in the city again. I am alive and am now walking through a trench. I am waiting for my military leave, to come and walk down Northern Avenue with you.”

And when they started granting military leaves, I would often meet up with the soldiers on Northern Avenue…

Don’t Despair

My parents did not know of my whereabouts the entire time. They only found out after the war. They would call me, but I would not answer their calls.

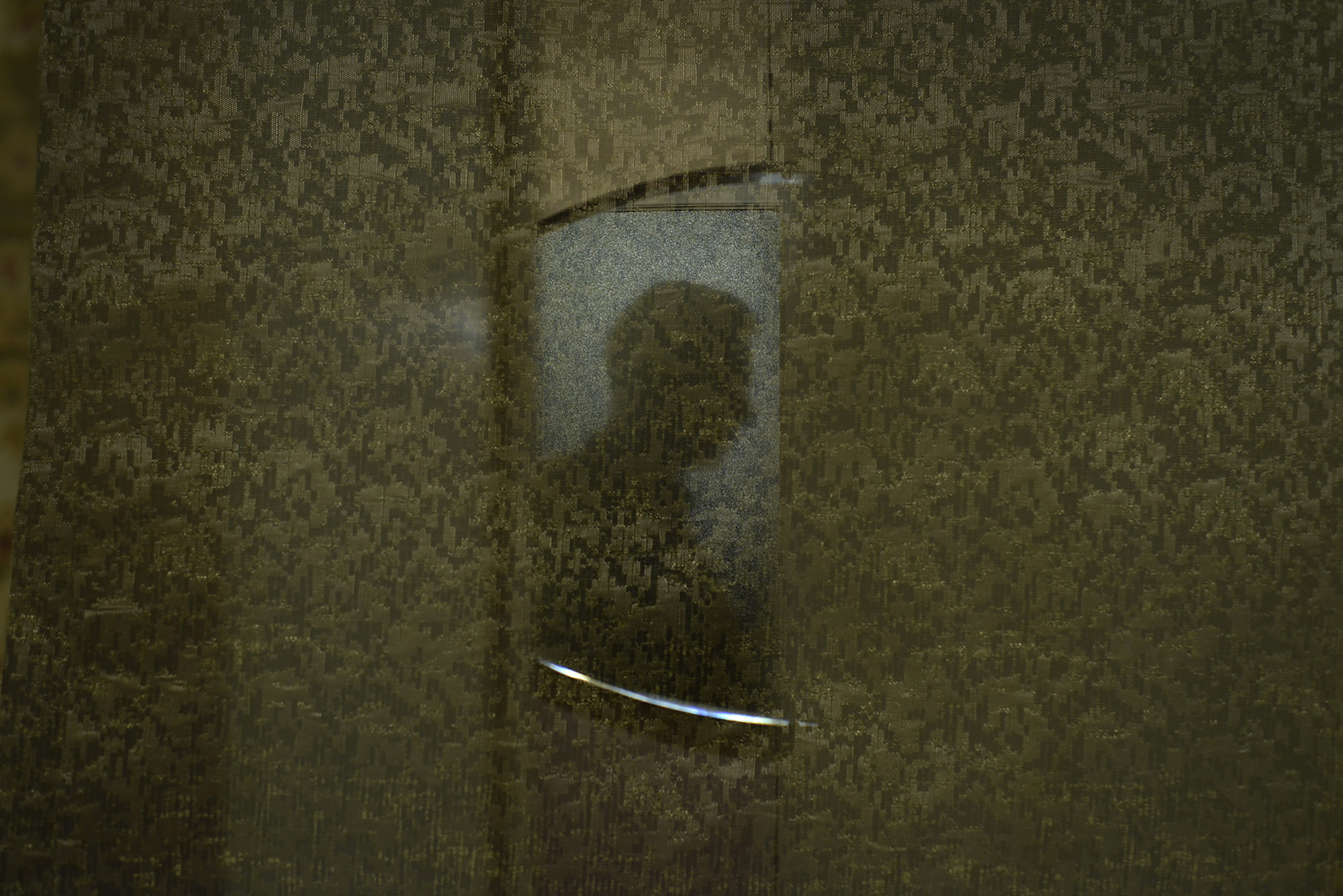

During the war, people often asked, “How does Arthur always remain positive?” But, that positivity was conditional… I always tried to work with a positive and joyful attitude, but I would cry in secret. On difficult days, my colleagues would help me; they had proposed I contact them and talk to them regularly, to share my feelings. Connecting with the world outside the war also helped in maintaining my vitality and optimism. When psychologists in Yerevan would organize online seminars with specialists from France or other countries, I sat under the bushes, listening to these seminars on my phone. And this helped me stay level-headed and live.

Grief

Working with grief is important. To this day, one can observe the transgenic transmissions of the destructive memory of the Genocide and the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, and the problems arising from them. Psychological intervention can help to work through grief and the memory associated with it, so that it becomes constructive. During the war, at the end of October, I contacted my psychoanalyst once more, and we resumed our work. I continue to see him.

“Grief is not simply another feeling; it is a fundamental anthropological phenomenon. There is not a single intelligent animal which buries its kinfolk. To bury is, consequently, to be a human being. However, to bury is not to throw away, but to hide and keep. Human grief is not destructive (forget, break away, distance) but constructive; its job is not to scatter, but to gather, not to destroy, but to create — create a memory.”

-Fyodor Vasilyuk