Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

“There have been wars before but Armenians, as well as Ukrainians, we have stayed and protected our heritage as much as possible,” says Anushavan Mesropyan. The 54-year-old translator was born and raised in Yerevan. Having studied Ukrainian language and literature, Mesropyan came to Lviv in 1991 for an exchange program. He ended up staying, marrying a Ukrainian woman and raising his two sons in the city.

“Now, my homeland is here. And I am not going anywhere. I am not scared,” he says. Mesropyan works as a translator, studying old Armenian manuscripts and translating Armenian literature into Ukrainian and vice versa. Like him, most of the Armenians in Lviv are planning to stay, despite the war. The sirens waking them up every night and the two bombings that occurred in the Lviv region are not enough to make them quit the lives they have built.

Established Roots

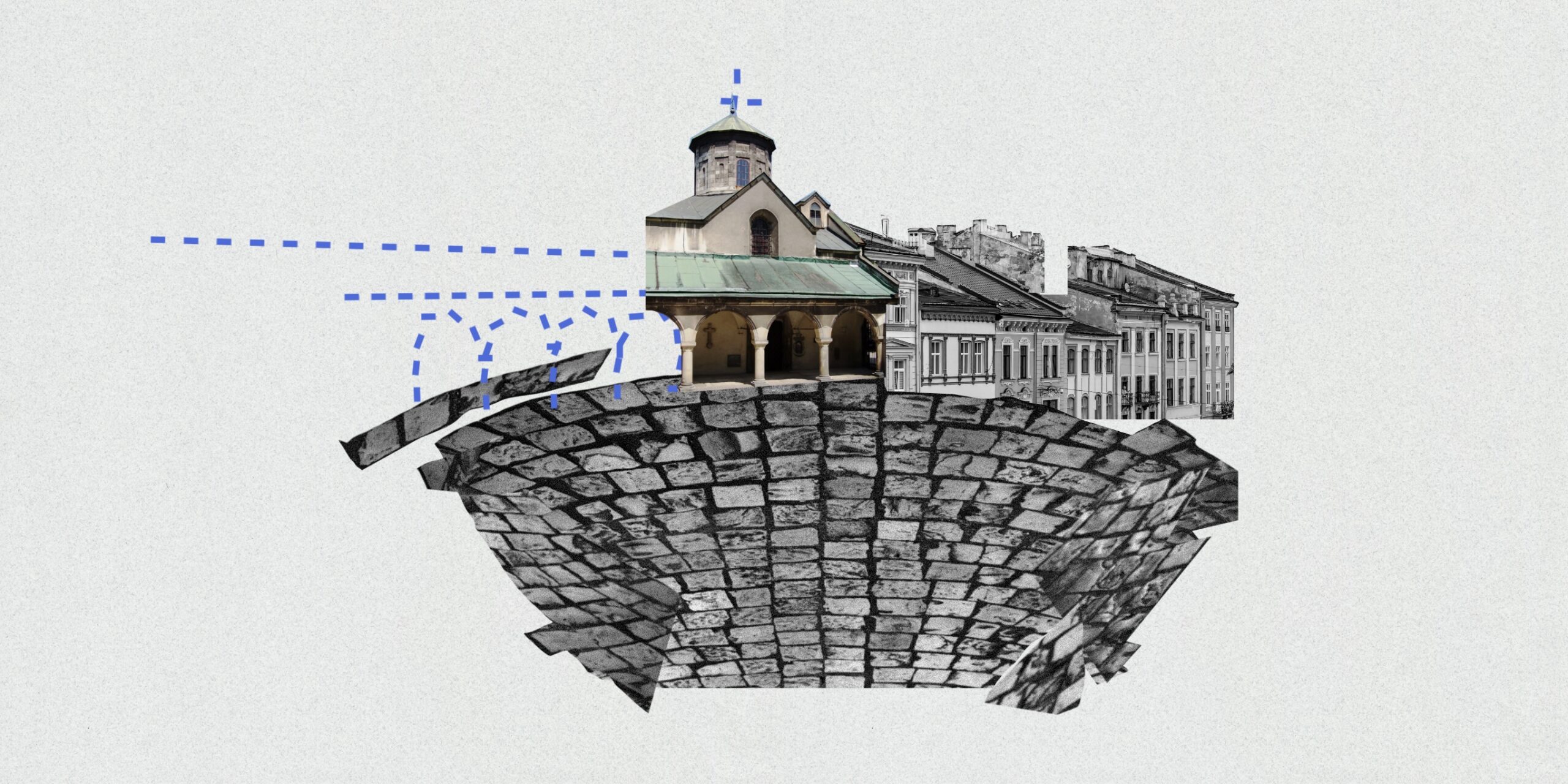

Armenians originally came to Lviv (then a part of Poland and spelled Lwow) in the 1040s, from the city of Ani, during wars between Armenia and the Byzantine Empire. The Armenian Cathedral in Lviv was built in 1363. Around it, a “Little Armenia” is still standing. Virmenska [Armenian, in Ukrainian] Street is located in the colorful old town of Lviv. It is a popular attraction for tourists. Around it, the Armenian café, Kilikia restaurant and the Para Janov Café are more modern reminders of the city’s medieval heritage.

Between 1946 and 1991, the church was closed, and served as a depot. Today, it is functioning once again, and locals can admire its unique frescoes. It was a spiritual home to Armenian Catholics until the city came under the control of the Soviet Union during World War II. Since the 2000s, it is operated by the Armenian Apostolic Church.

But most of the Armenians currently living in the city are not direct descendants of the medieval Armenian community. They moved here, and to other parts of Ukraine, during the Soviet era to follow employment opportunities. Some came here as refugees after the 1988 Spitak Earthquake, the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, or fled the pogroms against Armenians in Azerbaijan. Today, Ukraine boasts one of the largest Armenian diaspora communities in the world (after Russia, the United States and France). About half a million Armenians lived in Ukraine before the war.

The wooden Jesus Christ statue was removed from the church on March 5, to be stored in a bunker for safe keeping. The last time that happened was during World War II. Outside, some of the statues and ornaments have been wrapped in foam and plastic.

The Armenian church has refused to make any public statement about the war, fearing repercussions against the community. During a mass held in the Lviv church, the Deacon Artur made a prayer for peace, and reminded that this territory had hosted Armenians for centuries. He easily goes from Grapar to Eastern and Western Armenian, Ukrainian and Russian, and welcomes everyone to the church.

“Not My First War”

“One morning, I woke up from the sirens. That’s when I realized war was coming closer,” remembers Anatole Arakelov. The young videographer was born and raised in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, to an Armenian-Ukrainian father and a Russian-Polish mother. His parents met in Baku, and left for Ukraine during the pogroms. He is no stranger to conflict.

After living in the U.S. for several years and traveling across Europe, Anatole moved to Armenia to reconnect with his Armenian roots. In September 2020, when war erupted in Artsakh, he was in Armenia. “So this is the second time we face war already, it’s not my first war—I knew what to do,” says Arakelov.

The “we” refers to him and his girlfriend, Maretta Ayvazyan, who defines herself as an “Armenian with a Russian passport living in Ukraine.” Ayvazyan’s family was also originally from Azerbaijan and fled persecution. She was born and raised in Krasnodar, in Southern Russia. The couple decided to move to Lviv a year ago. They never expected to face a war of this scale in Ukraine.

“A few days before this war started, I was following the news and American intelligence, and I got worried,” says Anatole. “But I did not imagine anything like this.” Since Lviv is relatively safer than the rest of Ukraine for the time being, the young couple is helping out internally displaced Ukrainians.

Anushavan Mesropyan posing on a bench in Ruska Street, Lviv.

Inside the Armenian Cathedral in Lviv.

Maretta Ayvazyan and Anatole Arakelov inside the Armenian Cathedral in Lviv.

Maretta Ayvazyan and Anatole Arakelov posing next to the Armenian Cathedral in Lviv.

Photos by the author.

“We host relatives and friends, refugees,” says Maretta. “We prepared our documents, food, water, money and everything. We looked for the shelters,” recalls Anatole. “People started to flee from Kharkiv, Kyiv, Mariupol. We hosted many people who were heading to Poland,” he explains.

Though born and raised in Russia, Maretta never felt Russian because of the racism she faced in Krasnodar. She says she was constantly reminded that she was Caucasian and not Slavic while growing up. [In North America, the word “Caucasian” is often interchangeable with “White”. But in Russia, “Caucasian” is used to point out the darker features of people from the North and South Caucasus regions.]

Maretta feels more accepted in Ukraine. “I had been living here for several months before the attack happened, and people were friendly. Nobody said anything about my Russian passport, because they understood I was Armenian and didn’t support Russian aggression,” she says. “And Armenians and Ukrainians actually have more in common than they realize. We are all trapped in a toxic relationship with Russia.”

Anatole started relating to his Ukrainian identity in 2014. “When the Euromaidan revolution happened, it was like a wake up call for me. My relationship with Ukraine changed. I supported the Maidan and started being more active,” he says.

For Maretta, it was when Russia annexed Crimea that things changed. “I was confused. I thought it was weird to just go and take a region like that, without having a true understanding of why it’s bad at the time,” she says. “Now I think that being apolitical is also a problem. Not saying anything means you agree tacitly with what is being done. And I disagree with Russia’s invasion.”

“Not What Life Should Be Like”

Kristine Manukyan is 24 years old. The young illustrator was born and raised in Lviv, where her parents moved from Armenia in 1996.

“I have two homelands: Armenia and Ukraine. When the war started in Karabakh in 2020, I felt in the most profound way ever that I was Armenian. And now it’s the same: I realized how Ukrainian I am, too,” she says.

Kristine’s mother was in Armenia when the war started in Ukraine. She went to Poland with her sister for a few weeks to meet her mother, who took a flight to see them. But she will be going back to Lviv afterwards.

“I don’t want to believe that it’s going to get worse everywhere, even here. All my life is in Lviv, my work, my friends, my family,” she says. “We live next to the airport, so we decided to move. Each week we stayed with relatives or friends further away from the airport. The sirens are scary of course, even though we were thinking nothing would happen to us. You cannot sleep; you have to go to the basement. That’s not what life should be like. But we are not leaving Lviv.”

“We all have a ready-to-go backpack, for when we hear the sirens. But we have not prepared anything to leave. We are staying,” says Anushavan Mesropyan. Schools are closed, but his two sons are continuing classes online. Schools, stadiums and some religious buildings are used to stockpile food and host displaced persons.

“I followed the war in 2020 in Armenia, and that was hard for me, too. Now I get mad sometimes when I talk to some of my friends in Armenia. They watch Russian news and believe it and do not realize what is actually happening to us in Ukraine,” he says.

Anatole and Maretta say they believe Ukraine will be able to defend itself and have decided to stay in Lviv for now to try and help however they can.

Also read

The Fragile Situation in Artsakh in Light of the 2020 War and the Crisis in Ukraine

Sossi Tatikyan looks at the risks and opportunities for ensuring the security of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh in the post-war situation and in the current turbulent international context.

Read moreArmenia a Safe Haven for Russians and Ukrainians

Amid the war in Ukraine and economic turmoil in Russia, the Armenian government has been quick to open its doors to Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian citizens who want to relocate to Armenia or find temporary refuge.

Read moreDeconstructing the Divide: Armenia and Ukraine in Modern Eurasia

Armenia and Ukraine seem to have found themselves diametrically opposed on a variety of issues. However, Yerevan and Kyiv would benefit from a pragmatic relationship despite their seemingly disparate positions.

Read more