Dr. Lusine Sahakyan detected a tumor in a patient when she was providing free breast cancer screenings in Armenia’s rural villages, but the patient who was in her thirties did not want treatment. “If you are not going to sell your cows now to cure your wife, in two years time, you are going to have to sell them to pay for her funeral,” Dr. Sahakyan told the patient’s husband. Tough love, but like many cases in Armenia, familiarity around the screening and treatment of breast cancer remains scarce.

Breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer among women in Armenia. But many women were not going to the screenings when Dr. Sahakyan started providing them in 2008 with the Children of Armenia Fund (COAF). “They were scared that they will come and something will be detected,” recalls Sahakyan. Based on a study conducted by the American University of Armenia (AUA), the biggest reasons for high female breast cancer mortality rates are awareness, access, cost, lack of transportation, mistrust of healthcare providers, cultural beliefs, and the “underlying belief that cancer, itself, is incurable.” While the State now provides primary care coverage, mammograms are not carried out in most Primary Health Care facilities—what’s more, women are not educated on their importance.

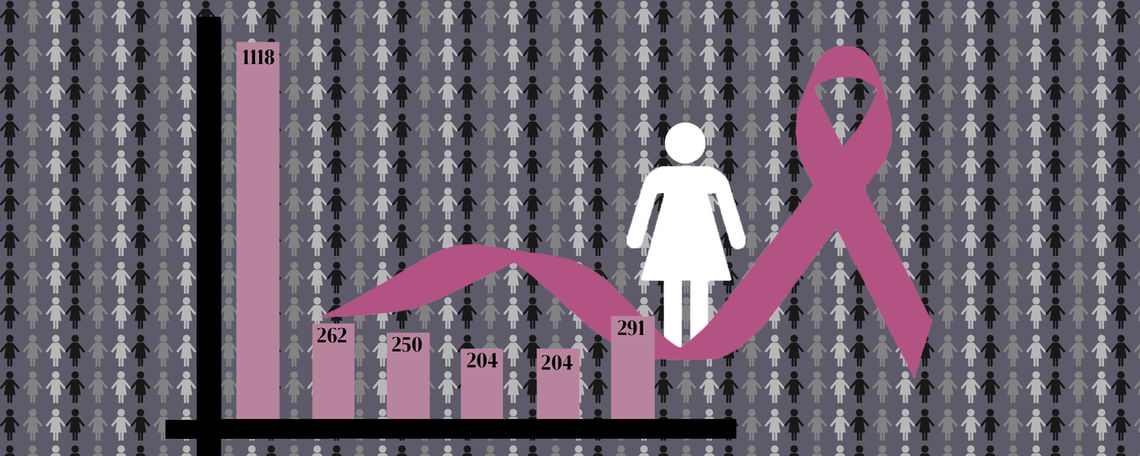

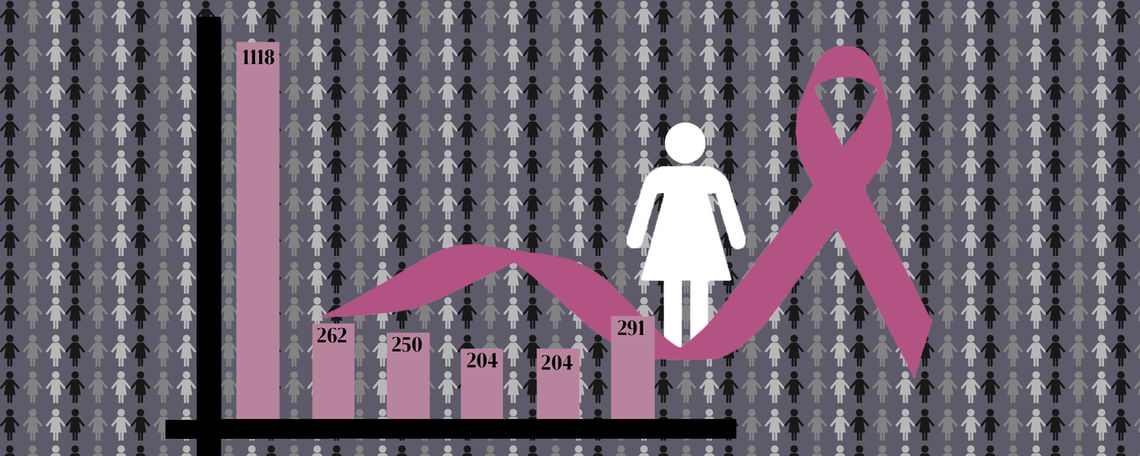

Between 2008 and 2014, attendance of Dr. Sahakyan’s screenings (physical examination and ultrasound) in six villages (Karakert, Lernagog, Dalarik, Myasnikyan, Yervandashat, Shenik, Armavir) increased tremendously through education, training and sharing success stories. The Armenian American Mammography Center has also been functioning in Yerevan since 1997 providing early detection, among other organizations. The mentality of declining screenings however, has certainly lingered within the country as a whole.

“We have a lack of demand,” says Dr. Varduhi Petrosyan, Dean of AUA’s School of Public Health. “Women don’t appreciate the importance of early check ups because of the mistrust. In terms of supply, providers working in primary health care facilities might not know how to do annual medical examination for breast cancer.”

Hripsime Martirosyan who runs Henaran, an organization conducting educational seminars for women about breast cancer, says that the distrust in the healthcare system also comes from women correlating high mortality to oncologists. “The unfortunate cases: people’s lives being lost, are outweighing the success stories,” she says. In fact, Dr. Sahakyan recalls that it took a few survival stories to generate higher turnout for her screenings. When COAF spoke to the Ministry of Health however, “the minister was quite inspired by the data, and a collaboration was launched,” she says. That collaboration is a new grant project providing mammography in three out of the 11 regions (marzes) of the country, which is scheduled to begin in early 2020.

The Ministry received a grant of $1 million US from the Eurasian Foundation for Stabilization and Development in 2018, to implement a mammography program in the three regions of Lori, Syunik and Tavush considered to be vulnerable border regions. The grant will cover one mobile mammography unit to travel throughout those regions for two years providing screenings targeting women between 50 and 69 years old.

Kristine Sargsyan is the Director of the Health Project Implementation Unit of the Ministry of Health and is responsible for the implementation of this project. She explained that they will closely collaborate with Primary Health Care (PHC) physicians. “General practitioners and physicians are the key responsible people who are going to work with the population to raise awareness and to send them for mammography,” she says.

According to Sargsyan, the project will also contain an educational aspect regarding information on cancer itself, risk factors, healthy lifestyle changes and self-examination training. Sargsyan says it will be a comprehensive approach and predicts 50 percent coverage with about 26,000 women attending the screenings. “We have already started developing research on PR to maximize participation,” she says. Regarding long term benefits, the mammography unit will go to the state funded Surb Grigor Lusavorich Medical Center in Yerevan after the two years, and local doctors will be trained to refer women to screenings, according to Sargsyan.

The grant project may increase public awareness and participation of screenings similar to COAF’s work. For the communities outside of these regions and those who have not received help from organizations, early detection is not always available at the moment, and screening is predominantly offered in Yerevan. Transportation to the nearest clinic is not always convenient and affordable for those outside the city. Martirosyan mentions that often, a woman might think that “if there is no evidence that I have something wrong going on, why should I spend extra resources to get screened?” Similarly, Angin Manukyan, an oncological nurse at the Institute of Hematology in Yerevan says that many of her patients are from outside of Yerevan, and “don’t see any issues, so they don’t go to mammograms until it’s too late.” Uttering the word cancer itself is in some cases considered sensitive as well: another AUA study describes that “there were women who learned about their diagnosis after having received their first chemo treatment.” Martirosyan concurs, explaining that families sometimes want to “protect” the patients by denying that they have cancer. This mentality is slowly shifting however, especially with the new government project in place.

Manukyan admits that while she has free access to a screening, she has not yet gone, although both sides of her family have a history of cancer—Manukyan does, however, regularly check herself. When a doctor at Hematology offered free screenings one year, she and her colleagues did not go because they worked with him and knew him personally, she says adding that doctors in smaller villages especially, know everybody in the community and women feel “ashamed” to be checked. While this is not to generalize all cases, it is important to note that increasing public awareness can change this mentality. At Henaran’s educational seminars which Martirosyan holds in some of Yerevan’s largest companies to maximize reach, she recalls often hearing the comments: “If I had known that a man would be conducting the seminar, I wouldn’t have come.”

Martirosyan, Dr. Sahakyan and Manukyan note that the mentality of preferring not to know if one has cancer and discomfort with the topic is quite common. The awareness of self-examination for early detection is also lacking, effectively causing women to present their diagnosis in the later stages (III and IV) which makes up over 20 percent of cases in Armenia. This is not only an issue for survival rates, but also for cost. If detected early (stages I or II), a cancer can be surgically removed for free as of February 1 of this year after a decision made by the Ministry of Health. At early stages, patients have an almost 100 percent survival rate, and may not require chemotherapy. If a woman does require chemo however, the path to being cancer-free is much more nuanced and also expensive.

“They take out loans from banks, sell their houses, get money from their relatives. If they are wealthy enough they will do that until they are bankrupt,” says Manukyan about how the majority of her patients finance their postoperative treatments. Only some are covered through the State or employers. One chemo round alone costs approximately $1,000 US on average, and radiation around $3,000 US, although different sources suggest that expenses vary depending on the individual’s case, but are burdensome nonetheless. One annual screening costs “between $30 to $40, which is roughly 9-12 percent of the average monthly salary in Armenia,” the AUA study states. Manukyan says that for many of her patients, the family had to work hard to convince the patients to undergo treatment because they “don’t want to be that burden.” She adds that women without families will often simply forego treatment altogether.

“Of course chemotherapy is very expensive, therefore it’s not feasible for a country with such scarce resources to cover it,” says Dr. Petrosyan. When it comes to Manukyan’s patients, they have to buy the chemo themselves and bring it to the oncologists which is a common practice in Armenia. Before this year, the availability for chemo coverage was limited to a very small category of socially vulnerable people. Recently however, the government expanded the amount of people who can be eligible for coverage and will pay for either 30, 50 or 100 percent depending on one’s category of vulnerability. This has been in place since June and greater access to radiation since July of 2019. As for the new mammography project, the grant will not be able to cover the continuation of treatment once a cancer is detected, but “there are steps and discussions being held with the Ministry and all responsible agencies,” says Sargsyan.

Important to consider with early detection are the different risk factors and levels of susceptibility which vary among women. While women at age 50 will be given mammograms (this is the standard in many countries), the age distribution of breast cancer actually begins at around 30 years old, and tumors are generally more aggressive before menopause. Aside from age, susceptibility factors also include family history, weight, reproductive state and many more uncontrollable elements.

A 2016 study sheds light on the issues of mammography, concluding that with over-provision, “women were more likely to have breast cancer that was over-diagnosed than to have earlier detection of a tumor that was destined to become large” causing unnecessarily vigorous measures such as biopsies, out of fear of the tumor. The solution is not as simple as offering mammography to women without first considering susceptibility and risk factors, as well as less invasive methods such as physical examination and ultrasound. With regards to the three regions receiving screenings from the grant project, “The protocols and guidelines that we are now starting to develop will cover all the issues, defining the risk population among even these target populations” says Sargsyan. Compared to cervical cancer which can be detected with a simple annual pap test that is universally offered, Armenia is slowly transforming how early detection of breast cancer is handled.

Regardless, the first step to refining these measures is general public awareness of their gravity and implications. Creating higher participation of early detection will be crucial in preventing women from having to sell their cows or homes to pay for long and painful treatments. As Dr. Petrosyan says, the hope lies in trained doctors and “a population who is aware of potential risks and go for more prevention. It is not easy, but it’s possible to improve the situation.”