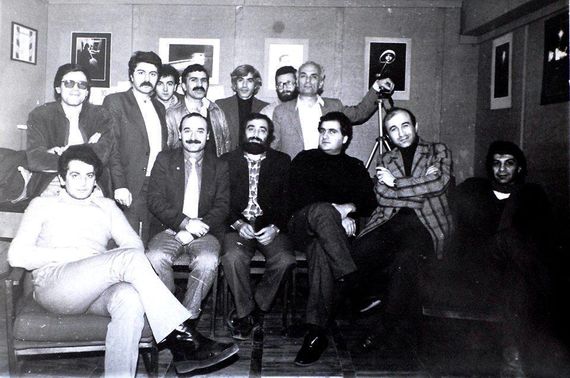

I am staring at a 1984 photograph taken at one of the regular meetings of the “Yerevan” photo-club – the most prominent organization of its kind in Soviet Armenia at the time. Assembled in two rows, thirteen members of the association stare back at the camera with reserved joviality. Framed examples of their photographs are displayed on the surrounding walls – all of them clearly experiments in “art photography.” After all, this was the period immediately preceding Mikhail Gorbachev’s era of Glasnost and Perestroika and Soviet culture had already set course towards de-politicization, endorsement of artistic subjectivity and the rehabilitation of aesthetic formalism as a valid component of socialist art. The photographers included in this 1984 group photo reflect this triumphant rise of individualism with each member flaunting their personal sense of fashion and taste – from buttoned-up shirts and ties to leather jackets and turtleneck sweaters.

The “Yerevan” photo-club, 1984. Photographer unknown.

But this display of apparent diversification hides a glaring absence that makes this otherwise ordinary documentary photograph uncanny and somewhat disturbing. All the club members in this image are men.

Formed in 1962, “Yerevan” was a pioneering effort that aimed to create an environment for networking and discussion between professional photographers in Soviet Armenia. Though other unofficial circles existed before, they were short-lived and did not have the “creative” focus of this specific endeavor. The absence of women amidst the members did not reflect some men-only policy or a hidden misogynist rhetoric. Simply put, there were no women in the field accredited as professionals. That is not to say that they were entirely absent. Rather, they were invisible. Perched behind the counter, retouching in the lab, or sometimes operating the camera (if the client wasn’t important enough) the female workforce had been a permanent part of the photographic industry since the 19th century.

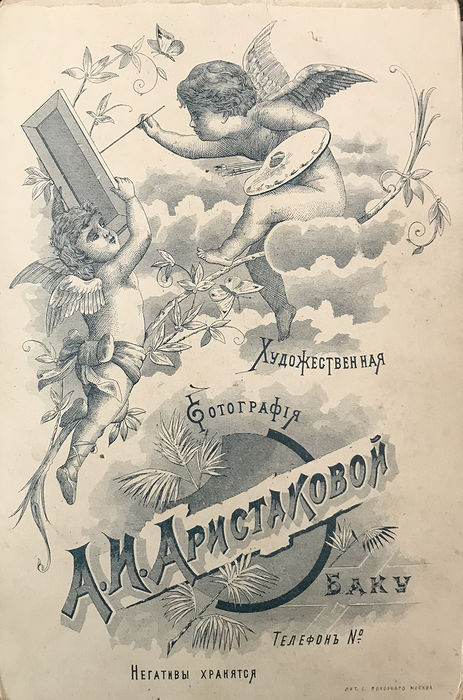

In some rare instances women were able to break out of this exploitative cycle when they were given the opportunity to take over the reigns of an inherited business from a sibling or a spouse. In the context of Armenian photography, we have examples like Elizaveta Musheghyants, running her father’s studio in Alexandrapol and later, Tbilisi, at the dawn of the 20th century. Her compatriot Ashkhen Aristakova made a go of it in Baku around the same time, but did not achieve long-term success. The recently rediscovered Mariam Shahinyan had better fortune with her Istanbul studio called Foto Galatsaray, which quietly thrived on wedding, childhood and theatrical portraiture between the 1930s and 80s. In the post-war period we find an unassuming woman named Shake, who had begun her career as an assistant in the iconic Cairo studio of internationally renowned Aram Alban in the mid-1950s. The heirless Alban was so protective of his dedicated companion, that he married her so that he could will her the business legally. Notwithstanding her small stature, Shake managed to keep Studio Alban a successful enterprise during the waning decades of traditional studio portraiture and put her stamp on this establishment, even to the point of adding her first name to the famous Alban brand.

The 2007 biographical dictionary of Armenian photographers compiled by Vahan Kochar, mentions two or three other women who ran studios in Soviet Armenian towns between the 1940s and 80s. As usual, these were operations organized around family collectives, in which the women had eventually taken the supervising roles as a way for sustenance, rather than any particular desire. Some other names such as Satenik Gibrianosyan, Annie Karakaian and Hasmik Matosyan were discovered in the course of research for Lusarvest – the comprehensive online database of Armenian photo-media practitioners initiated by the Lusadaran Armenian Photography Foundation. Nevertheless, of all these women, only one – the Egyptian-born, London-based Ida Kar – succeeded in working her way into the pantheon of photographic history. She managed to do this through countless tribulations, including her staunch rejection of her Armenian family’s conservative views regarding the “appropriateness” of her career and lifestyle choices.

Kar was the exception that proved the rule and unless providence helps us to discover a long-lost Armenian Vivien Meyer, all evidence points to the fact that photography was not deemed a suitable occupation for women in Armenian communities either in the 19th or 20th centuries. Why this was so, may be partially explained by the overall rhetoric of functionalism that surrounded photography’s uses – particularly in Soviet Armenia. Primarily serving the objectives of state-controlled mass media, local photography was also tied to the domain of a social infrastructure that entailed everything from passport photographs to commemorative family portraits. In this context, the supposedly feminine attentiveness to detail was deemed as a suitable aptitude only for negative retouching, bookkeeping, set decorating and other such tasks. But the job of creating an image, whether for media or personal purposes, was too anchored in a very public display of “recording” and “gazing” that ran against the strict codes of suitable female behavior in a society that held women as beacons of moral virtue.

In terms of standard documentary photography, the practical necessity of working long, irregular hours amidst crowds, on streets or in remote areas, meant that women would have to often break from their regulated regimes as wives and mothers – something that few were willing or able to do. More perniciously still was the fact that until the late 1980s, and despite the efforts of a few dedicated believers like Andranik Kochar, Nemrut and Gagik Harutyunyan, photography was utterly ignored as a medium of individual artistic expression in Armenia. This helps explain the schism between the large number of Armenian women engaged in painting, sculpture, literature and even architecture, and their dearth behind the still or moving image cameras. A mechanical device that mostly spun-out uninspired news reportages or tasteful mementoes for the family album, photography was, quite simply, not worth the trouble.

But, the upheaval of the 1988 Spitak earthquake, the Karabakh War and the collapse of the USSR in 1991, brought a renewed urgency to photographic documentation. It was no longer enough to merely relay or record events. What was needed was more than a gaze: in the aftermath of the Soviet Empire, the photographer had to become a mediator who sifted through the chaos in order to find some sense. It is precisely in this context that women sporting photo-cameras begin to appear in Armenia.

Interestingly, it was the diasporan women who initially broke the mold. In some of the archival video footage documenting the earthquake relief efforts or the parliamentary elections of 1990, one can spot the Detroit-based Michelle Andonian and the Parisian documentarist Armine Johannes determinedly going about their business in a sea of men. Their presence in Armenia was an anomaly, and though both photographers returned to Armenia in the following years, they did not directly spawn a generation of local female photographers. And yet, they were a clear example that Armenian women could, in fact, become successful at this profession and present alternative perspectives on current reality.

On the other side of the spectrum, the Iranian-American artist Sonia Balassanian had arrived in Armenia to establish a new center of contemporary art (Armenian Centre for Contemporary Experimental Art – ACCEA) together with her husband, Edward Balassanian. An established video artist, Ms. Balassanian curated a number of exhibitions at ACCEA that put a special emphasis on photo-media art. This, in turn, encouraged numerous local women artists to take up photo-media as their primary means of practice at the dawn of the 21st century. The pronounced criticality and aesthetic bluntness of Karine Matsakyan’s, Diana Hakobyan’s, Astghick Melkonyan’s and Sona Abgaryan’s photographic and video performances, brought a hitherto unseen willingness to show and speak about subjects that were either too controversial or abject to be addressed in Armenian visual culture. It is this realization of photography’s ability to expose and break social taboos that has underlied women’s engagement with the medium in Armenia since the early 2000s.

Ashkhen Aristakova’s Baku studio backstamp. 1900s.

Elizaveta Gavrilovna Musheghyan. Portrait of Arpik and Siramarg Kanayans, Alexandrapol, 1900s. Courtesy of National History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan.

Shake Alban. Wedding portrait, Cairo. 1960s. Lusadaran Armenian Photography Foundation.

Like most ex-Soviet countries, Armenia was also a mini-lab for socio-cultural experiments initiated or supported by various European and American organizations that were eager to prod the country onto the path of westernization and integration into the capitalist system. One such project was the photojournalism course initiated by the newly-founded Caucasus Media Institute in 2004. Run by the renowned photo correspondent Ruben Mangasaryan, this was essentially the first accredited, professional training course for documentary photography ever held in Armenia. The initial one-year program led to an independent course designed by Mangasaryan, which attracted a significant number of enthusiastic twenty-somethings drawn by Mangasaryan’s international reputation and the chance to enter the adventurous field of photo-reportage. Few could have possibly anticipated that these courses would become a boot camp for a veritable brigade of local women photographers.

Nazik Armenakyan. From the series ‘The Stamp of Loneliness’. 2011.

The 2004 cluster was comprised of practicing photojournalists from ex-Soviet countries, among whom was Nazik Armenakyan – one of the first local women to enter the profession. Coming from an arts background, Armenakyan had experimented with painting and writing, prior to taking up photography as her primary medium. She firmly pushed her way into the ranks of working photographers, getting a job at the Armenpress photo agency in 2002. Right up until his untimely death in 2009, Mangasaryan put a special emphasis on engaging and supporting female students. Many currently practicing photographers such as Anahit Hayratepyan, Piruza Khalapyan, Inna Mkhitaryan, Anna Davtyan, Aza Andreasyan, Nvard Yerkanian and Nelly Shishmanyan started their careers in photography under Mangasaryan’s tutelage.

But, whatever their background, the fascinating thing about these emerging new forces in photography was the combination of common imperatives and the desire to carve out an individual approach. While going on to form groups, networks and teams, these photographers have gradually focused on their own interests, compulsively honing a personal vision that could also speak to urgent, collective questions from a personally engaged perspective. But how was this work meant to be reinforced and reach the public in a context that lacked established infrastructures for the production and reception of documentary or art photography? To be a professional in this field meant either hustling for very limited and badly paid jobs in the mass media, taking the commercial route or basically going into the financially unpredictable wilderness of independent practice. As Armenakyan states, most of her early career “was spent trying to prove that I could do the same things that male photographers could do.” As can be expected, the odds were stacked against women, most of whom also had young children to care for and faced considerable resistance in a society not accustomed to talking about intimate and morally contentious matters. And as time would prove, these were precisely the kind of questions that women were interested in exploring.

Despite the obstacles, the 2000s was a decade of bustling activity that consolidated the fact that a female-led generation of documentary and art photographers had assumed the stage, bolstered in part by international, grant-based civil-society projects as well as contemporary art initiatives. When I curated my first photographic exhibition in Armenia in 2011 (Industrial Symphony, ACCEA, Yerevan), half of the twenty participants were women. They had been consistently turning their attention to topics that spoke to their own experience of social marginalization, discrimination and the problems of historical memory. Tentative first attempts eventually led to outright confrontational projects whose full scale and relevance was revealed in a range of exhibitions organized in the first half of the 2010s. In the 2013 all-female group show “mOther Armenia,” ten photographers had turned their lens on aspects of Armenian reality that generally remained lodged within the netherworlds of public consciousness. Anahit Hayrapetyan showed a shocking portrait of domestic violence suffered by women next to unflinching photo-essays on peasant and refugee poverty by Mary Aghakhanyan and Inna Mkhitaryan. More provocative still were the investigative series on Yerevan’s transgender community by Nazik Armenakyan, Sara Anjargolian’s probing into the non-combat deaths in the Armenian army and Anush Babajanyan’s striking portraits of “Outlandish” women whose extravagant garbs defied norms of “decency” on Yerevan’s streets. More subtle, albeit no less pertinent were Piruza Khalapyan’s photographs depicting Armenia’s Yezidi community and Nelli Shishmanyan’s gently ironic look at the issue of urban waste. The narratives and characters brought to public scrutiny in these works had rarely (if ever) been accorded representative significance or been treated with such empathy.

Curated by Svetlana Bachevanova, “mOther Armenia” was organized by the 4 Plus Documentary Center formed in 2012 by Armenakyan, Babajanyan and Hayrapetyan. The collective has steadily evolved over the past years and currently operates as an important platform for the production and dissemination of socially-engaged documentary photography in Armenia (both by women and men). Such collaborative, self-mobilizing tactics have played a key role in affirming the place of women on the local photography scene. Their determination to continually probe the most painful and sensitive areas of life in Armenia has often meant that these documentarians are often on the frontlines of local conflict zones, such as the anti-government protests of 2008 and 2018, as well as the farthest and most neglected areas of the country. The strong sense of photography’s social responsibility defines both the proactive intent and the formally raw realism of their oeuvre. This staunch belief in the medium’s ability to have a direct impact on reality is an aspect that sets apart the work of Armenian female documentarians from the more self-conscious and critically vigilant approaches of their Euro-American peers.

At times this unshakable investment in the oft-decried “objectivity” of photographic reflection can appear like perceptual naiveté, blanketing photography’s politically grounded mediation of the world. Realizing this disjuncture, a number of women photographers have gradually moved away from traditions of “straight” documentation to explore the inherent ambivalences and conceptual complications of the medium itself. We can observe these developments in the work of independent photojournalist Ani Gevorgyan, whose pointedly aestheticized reportages turn current events into strangely haunting hybrids of 1920s avant-garde photography and investigative journalism. In a similar vein, both Piruza Khalapyan and Anush Babajanyan have turned to more subjective explorations of historical and environmental dilemmas (post-industrial cities, the ecological disaster threatening Lake Sevan and so on) as a way relaying their specific, personally grounded experiences of these issues. The question of the “female gaze” in general has become prominent in debates surrounding the current state of photography in Armenia as it has elsewhere. Some reject any kind of gendered differentiation in line with theoretical critique of homogenous understanding of the term “woman” by the likes of Judith Butler and Rita Felski. Others, meanwhile, hold out the position of difference as a way of resisting the still predominantly patriarchal structure of Armenian society and culture.

Regardless of how one perceives the matter, it is impossible not to see the way photography by persons who mostly identify themselves as heterosexual women (in tandem with representatives of queer or minority groups) continues to act as an intervening, deconstructive and critical force, which unfixes our certainties about social reality and the work of photography itself. This tendency is especially marked in the works of photo-media practitioners like Anna Davtyan, Lusine Talalyan, Irina Grigoryan and Svetlana Antonyan who work in the grey zone between contemporary art, political activism and documentary photography. What their ambiguous images reveal to us is not simply the deeply uncertain state of humanity today, but that reality is a multifarious beast in a constant state of transformation, shaped by the ebbs and flows of time and history, power hierarchies and culturally anchored individual experiences. It is this quaveringly fluid perspective that is embodied by Anahit Hayrapetyan’s 2010 self-portrait series “Since I am Pregnant” – a poignantly fearless ode to uncertainty and emotional openness that stands like an antithesis to that 1984 group portrait of Yerevan photo-club members.

In a culture struggling to define its own identity against the incessant pressures of globalization, capitalism and the existence of the multiplicity of voices and histories within its own fabric, such revelations are of immense value. To be blunt, the work of women photographers within less than two decades has been instrumental in showing the cracks, flaws and hidden crevices of the monolithic disciplines that have governed Armenian society for centuries. They have achieved this without any help from governmental bodies or much support from the public. Ironically, it is also thanks to their inherited status as nurturers, educators and, generally, models of public virtue that has provided women with the power to speak about the unspeakable, approach the unapproachable and touch on the kind of divisive issues that would be considerably more difficult to access for many of their male colleagues. Few in Armenia would dare to question the integrity of a woman sporting a camera and a newborn baby on her back. More crucially still is how photographic stories produced by women have steadily diversified the spectrum of visual representation in Armenia, creating vital channels for communication between different segments of Armenian society as well as the country’s neighbors and the world at large.

This imperative to induce empathy and constructive dialogue is perhaps the only primary characteristic that binds the diversity of means and varying trajectories that are explored by local women photographers and photo-media artists today. Their emergence in the post-Soviet space is in itself a testament to the speed with which socio-cultural realities can change for the better when people find the will to come together and challenge the orders that suppress freedoms, silence voices and limit our capacity to see beyond preordained frameworks.

Anahit Hayrapetyan. From the series ‘From Princess to Slave’. 2013.

Nelly Shishmanyan. March 2. After the protests. 2008.

Anush Babajanyan. Zena and Barakis, 7, pose for a portrait on a street in the Koumassi district of Abidjan, Ivory Coast on July 25, 2017.

Ani Gevorgyan. Police. 2014.

Piruza Khalapyan. Metsamor. 2017.