After Azerbaijan and Armenia signed a ceasefire statement in November 2020, a peace deal between the two countries that would finally recognize the borders of the two countries and provide stability to the South Caucasus was expected. However, just two years after that ceasefire was brokered, fighting broke out again,this time along the eastern border of Armenia proper. After mutual accusations and loss of life, Azerbaijan announced that it had gained control of several strategic locations in southern Armenia. Baku also claimed that Armenia, including its capital city of Yerevan, is actually Azerbaijani territory.

At the same time, parts of the Azerbaijani public opposed the actions and statements of the Azerbaijani government: Azerbaijani activists who opposed the limited but symbolic occupation of Armenia and who rejected official arguments questioning the existence of Armenia were targeted on social media. Ignoring these oppositional voices of Azerbaijani society, the Turkish opposition and Turkish government were vocal in their unconditional support for Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, the Lemkin Institute for the Prevention of Genocide, named after Raphael Lemkin — the inventor of the term genocide — called the language used by the authorities and state-controlled media of Azerbaijan “genocidal” and drew the attention of international organizations to atrocities committed by Azerbaijani soldiers. Simultaneously, Mustafa Destici, Chairman of the far-right Great Unity Party, a member of the People’s Alliance (alongside the ruling Justice and Development Party and Nationalist Action Party), threatened to erase Armenia “from history and geography”.

But how do young Armenians in Turkey, who were born in the late 1980s and 1990s, feel about the use of genocidal language, which is not just used by ultra-nationalist groups? Since the war in 2020, during which Turkey provided military and political support to Azerbaijan, Armenians in Turkey have felt increasingly isolated. Threats to “erase Armenia”, as well as the lack of concern among the democratic opposition for the pain and trauma caused by the war on Armenians, seem to have weakened the hope of Armenian youth to live safely and peacefully in Turkey.

“We Were Reminded That We Are the ‘Other’ of the Other”

We, the Istanbul Youth Research Center, attempted to understand the experiences and perspectives of Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish youth with various religious, sexual and political identities and belongings.This qualitative research project was supported by the Hrant Dink Foundation. One of the major focuses of the study was how Armenian youth have been impacted by political developments in Turkey since 2007.

Hrant Dink’s assassination in 2007 sparked a response that the orchestrators of the murder could not have anticipated. Tens of thousands of people attended Dink’s funeral, expressing shock and anger at the assassination. The public closely followed the trial process, and every year on January 19th, thousands of people gather in front of Agos, the Turkish-Armenian newspaper that Dink headed, to commemorate him.

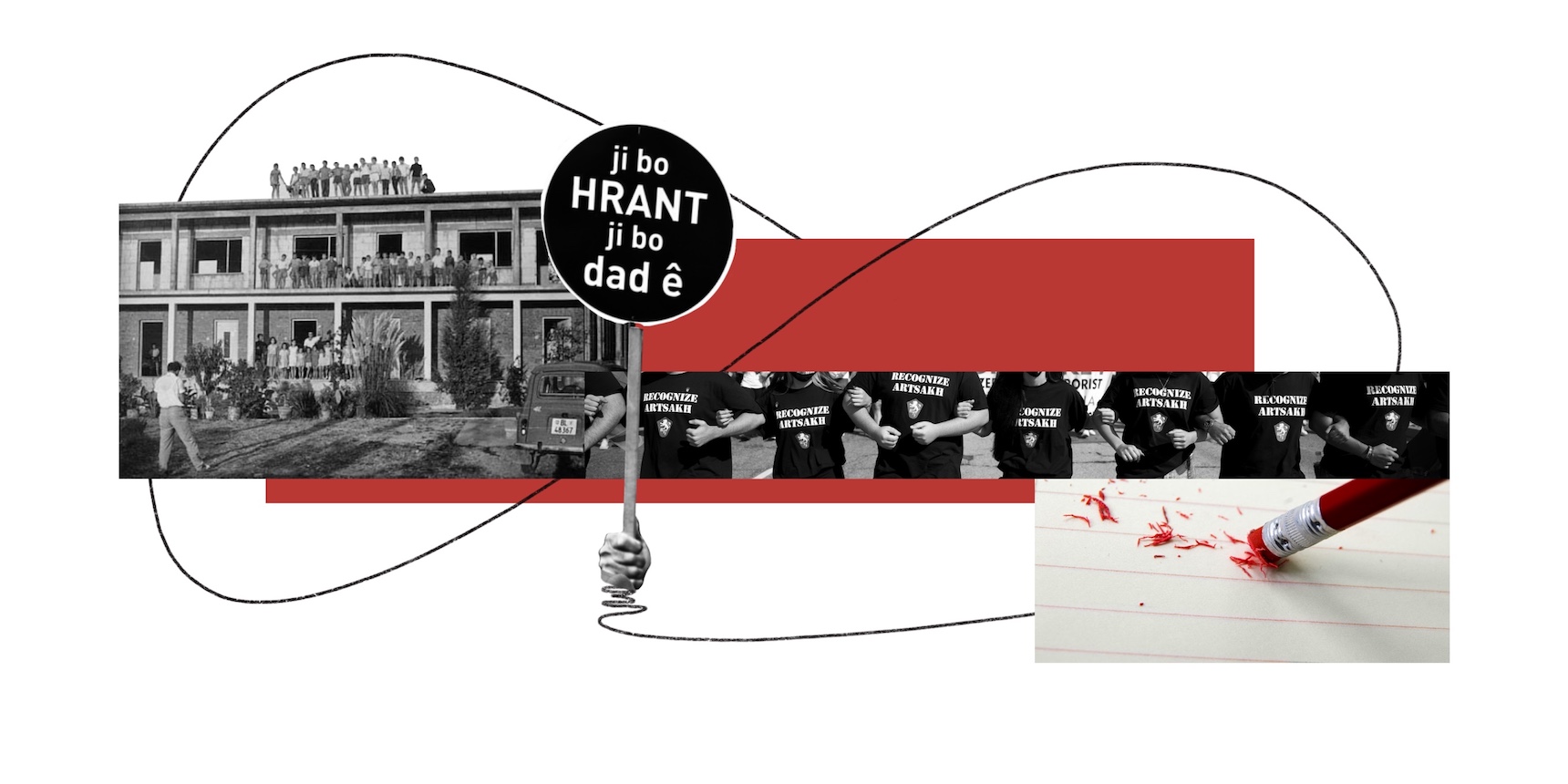

The youth participants in our study, including Armenians, Turks and Kurds, narrated January 19th as a turning point in their political engagement. This shared narrative highlights the significance of Hrant Dink’s assassination and ensuing memorial ceremonies and marches as a pivotal foundational event. Hrant Dink’s murder and the coalition-building that took place after 2007, including mass protests at his funeral, commemorations on Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, and resistance to the eventual demolition of Camp Armen in 2015, played a key role in shaping a new political identity and subjectivity among youth in Turkey. In other words, Hrant Dink’s assassination and the solidaristic-coalitional spaces created by Armenian community and the democratic opposition in its aftermath helped to forge and solidify a new shared political orientation among youth towards issues related to the Armenian genocide, the nation-state, identity, memory, and justice. Researchers in Turkey have been referring to this generation as the “January 19 Generation”.

In the shared memories of older generations in the Armenian community in Turkey and the diaspora, Hrant Dink’s murder was viewed as another episode in a series of injustices dating back prior to 1915. However, the most remarkable aspect of the shift after January 19 is that it has become a historically significant event with a profound impact on the political activism of Armenian youth, fostering a sense of unity and shared political perspectives among them. They established and joined Armenian youth-led organizations and cultural initiatives, such as Nor Zartonk, after Hrant Dink’s murder. Furthermore, through their trajectory of politicization, young Armenians began bringing contemporary social demands — in addition to demands around historical justice including recognition of the Armenian Genocide — to the forefront of public attention. Thus, Armenian youth in Turkey became an intersectional actor in the public-political space, active in various causes including ecological, feminist, and LGBTIQ+ rights movements, as well as in student activism. As a result, connections between Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish youth and other pro-democracy groups were strengthened. The political journey of the “January 19 Generation” sustained between 2007 and 2015. The youth-led movement organized in 2015 by Armenian, Turkish, and Kurdish activists to prevent the demolition of Camp Armen in 2015 was a notable example of the solidarity and coalition-building efforts of the January 19 Generation.

However, the 2020 Artsakh War was another defining moment in the political engagement of young Armenians in Turkey. One of the key findings of our research was that efforts towards coalition-building between Armenian youth and the public opposition in Turkey have been severely weakened during the war. The fact that most of Turkish society sees itself as a party to the 2020 war and the ongoing conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and the fact that Turkish society generally takes Azerbaijan’s side as if watching an international match, has caused significant fear and anxiety among Armenian youth from Turkey. The display of Azerbaijani flags in neighborhoods where Armenian migrant workers and Armenians from Turkey live, as well as verbal attacks directed at Armenians, have had a profoundly detrimental impact on the Armenian community. Young Turkish-Armenians, meanwhile, have been involved in activism for social change despite the ongoing state of emergency in place since the failed military coup in 2016. One member of this young generation, Ararat (23 years-old), who was interviewed during the research, highlighted how the current sense of alienation among Armenians has reawakened past traumas: “Armenians were again in a state of unease. Because there are traumas of the past: massacres, genocides, migrations, persecutions… A series of bad memories, one after the other. It is also difficult to get over those memories.”

The lingering trauma of past acts of mass violence against Armenians in Turkey and the fear that such atrocities could occur again amplifies feelings of desertedness and frustration among Armenian youth. Avedis (23 years-old), who has been involved in activism post-2016 under an increasingly authoritarian presidential system, describes this feeling as being “reminded that we are the other of the other.” Another young man, Nartos (30 years-old), who became politically active in high school following Hrant Dink’s assassination, states, “I thought I had very good non-Armenian friends, but I realized that they were actually anti-Armenian.” Many interviewees reported that they are exposed to violence both through a narrative of a constructed “us” that excludes them as well as anti-Armenian war slogans in the media and at school and work. The damage to their sense of citizenship and belonging in Turkey and the portrayal of Armenians as the “enemy” or the “other” has caused Armenian youth to withdraw into their shells — effectively meaning they withdraw from the public sphere. Another interviewee, Zakar (28 years-old), describes this as “feeling like hostages in our own country rather than true citizens of this land.”

The Armenian youth we interviewed expressed that they were not shocked that the majority of Turkish society participated in anti-Armenian sentiments. What disappointed them was that those who were on their side politically and emotionally — including social media friends and ecology activists — were silent and apathetic when it came to creating democratic public-political spaces in Turkey during the Artsakh War. This undermines the January 19 Coalition established among Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish youth as well as other democratic actors in the public-political arena. Armenian youth in Turkey had only their own Armenian community and friends to turn to: as Talin (28 years-old) shares: “But a border is drawn in one’s heart. You understand again what we should and shouldn’t talk about (with non-Armenians).”

“The Only Reason Armenians Stayed in Turkey After Hrant Dink’s Murder Was That Crowd”

The memory of Hrant Dink’s murder in 2007 and the memory of the coalition that formed in response to it is still strong among Armenian youth. They view Dink and the January 19 Coalition as a source of inspiration and confidence to stay in Turkey. As Talin (28 years-old) notes: “Seeing people at the April 24th commemorations or that crowd on January 19th… That crowd was the only reason Armenians stayed in Turkey after Hrant Dink was killed. Seeing that crowd still today encourages us to stay here.” For young Armenians, Hrant Dink’s murder and the January 19 Coalition are not only past events, but also hold historical importance that continues to shape their relationship with Turkey, their political beliefs, and their aspirations for a democratic society.

Turkey’s growing authoritarianism post-2016 has diminished the aspirations of young people for the future. In this oppressive environment where economic and democratic crises intersect, it is becoming increasingly difficult for youth to see Turkey as a place to realize themselves. In the post-2016 period, young Armenians have experienced another significant shift in their political orientation — a decrease in their involvement in activism due to disappointment with those they previously saw as allies. This new reality is causing young people to retreat into their own identity groups. The silence or even complicity of democratic political actors in Turkey, including the Turkish left and democrats, intellectuals, and civil society, has not only weakened the hopes of Armenian youth for a peaceful coexistence, but also greatly hindered political progress made from 2007 to 2015. We find that the narratives of Armenian youth around the alienation they experienced intensely during the Artsakh War deserve genuine interest and attention among democratic opposition and civil society actors in Turkey.

Could Everything Be Explained by Authoritarianism?

It would be wrong to explain the sense of isolation of Armenian youth only through the hegemony of Turkish nationalism and the closure of the public sphere to free discourse. The Armenian Genocide, for example, is a deeply taboo subject in Turkey because it that necessitates a critical re-examination of the founding and liberation story of the Turkish Republic. However, there is a counter-public space where knowledge about the genocide and its aftermath can be accessed and different political positions can be taken on this issue — something seen as a security threat in the Republic of Turkey. Over the last two decades, academics, researchers, publishers, and activists in Turkey have accumulated a significant body of knowledge about the genocide. This knowledge has contributed to various left-leaning organizations and traditions to support both the Armenians’ calls for historical justice and recognition of the genocide, despite the Turkish state’s strict censorship policies. It has also allowed for a stance that critiques the entrenched silence of the Turkish left in the face of a century of official denialist policies.

Since the 1990s, the left in Turkey has been unable to take a clear stance on the so-called Karabakh Issue due to ideological reasons, and has failed to take a principled position against official Turkish nationalist discourse. Many socialist organizations and intellectuals believed that real socialism was the answer to problems arising from nationalism, and attributed ethnic conflicts that emerged with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia to a capitalist distribution problem and nationalist reaction. This belief ignored the connection to the vivid memory and trauma of the Armenian Genocide, which was a root cause of the decades-long conflict between Soviet Armenians and Azeris (or Turkish-speaking Azerbaijani peoples). In fact, fear that the fate of Artsakh Armenians might be similar to that of the Ottoman Armenians spread even before the Soviet Union fell apart. This fear was reinforced when minor clashes between Azeris and Armenians in Artsakh turned into organized pogroms against Armenians in the city of Sumgait, creating irreversible distrust between Armenians and Azeris. The lack of interest from leftists in Turkey in the South Caucasus, combined with the tendency to explain the complex Karabakh issue with simplistic ideological explanations, has prevented progressives in Turkey from providing an alternative to Turkish nationalist and Pan-Turkish theses.

Given this context, what can progressive activists and movements from Turkey, many of whom have had to leave Turkey, do now? As they reflect on the historical silence of Turkey’s left in the face of the 2020 Artsakh War, it is crucial to carefully consider the new but intense impact of this issue on the Turkish-Armenian community, particularly on the younger generation.

However, it would be incorrect to limit the disappointment experienced by Armenians solely to those in Turkey. After Hrant Dink’s murder, academics, journalists, and activists from Turkey have been successful in building new relationships in Armenia and the Armenian diaspora. It is true that these relations have weakened as a result of the failure to establish “normalization” of state relations between Armenia and Turkey. However, the silence and lack of response from Turkish academics and activists during the 2020 war and clashes have also disappointed Armenians in Armenia and the diaspora — people who have worked and cooperated with them. This situation flags a crucial question to ponder for Turkish activists, who still believe that Armenians, Turks, Kurds, and other peoples can live in peace in Turkey and the Southern Caucasus: How can the recent trauma and disappointment experienced by Armenians in Turkey and around the world be eased?

Special thanks to Narod Avcı, Rudi Sayat Pulatyan and Özgün Muti for their valuable contributions to the research and this article.

Also see

The Eternal Minority?

Armenians scattered globally share one very prominent reality: they represent a minority status, writes Paul Mirabile arguing that the Armenians' numerical “weakness” has forged a most extraordinary but, at the same time, a most tragic reality.

Read moreRedefining Home: Overcoming Feelings of Unbelonging in Children of the Diaspora

Suspended between two worlds, many Diasporan youth struggle with the question of belonging and the looming discomfort of never feeling able to maneuver through either culture.

Read moreA New Generation of Istanbul Armenians

This article explores the changing and evolving mindset of young Istanbul Armenians not only through a sociological lens but through a political one, exploring the history and changing political landscape of Turkey and the clear power distinction that exists between Armenians and Turks.

Read moreThree Apples: The Relic

After decades of moving from city to city, writer and journalist Paul Chaderjian ends up with a relic that has no place in his two suitcases of mere essentials. A personal story that comes full circle from orphanages in Aleppo to civil war Beirut to Fresno and New York to Doha and Istanbul.

Read moreEthiopian-Armenians: Ancient Allies and Imperial Confidants

Ethiopian-Armenians are emblematic as a diaspora community that balanced their civic and cultural identities to build a prosperous and trusted community.

Read moreCanadian-Armenians: From Highlands to the Farmlands of Georgetown

In the early 1920s, 148 orphans of the Armenian Genocide were brought to Canada to begin a new life. They were known as the Georgetown boys and girls and their legacy forms the basis of the Canadian-Armenian story.

Read more