Going forward, all English language articles on EVN Report will have audio versions.

Listen to the article.

I grew up in a predominantly female environment, with conversations around the coffee table revolving, in an endless spiral, around family issues and problems not voiced outside of this circle. I liked hovering around the living room, privy to those candid confessions shared between women. The common thread in these conversations was the domestic issues associated with living in multigenerational, extended families.

Looking back as an adult, I realized that these seemingly interpersonal conflicts were more often than not rooted in social, economic, cultural and even political issues. These problems and their causes are multifaceted. The realities these women shared over cups of coffee often foreshadowed the challenges awaiting a new family.

“There were no separate rooms for his many sons, each of whom had a large family. They all lived in one room, under one roof, which was nothing more than four walls covered with logs. This is where the hearth was lit, the baking was done, food was prepared, and where they all ate and slept,” so goes the depiction of Khacho’s family in Raffi’s late 19th century novel, “The Madman”/«Խենթը». Khacho’s family included his seven children, their wives, and sometimes even the families of his grandchildren.

This would be today’s multigenerational family, where three or more generations live under the same roof. While this is the traditional family structure in Armenia, the nuclear family is more “traditional” in countries like the United States or Canada.

Growing up, I often heard complaints about multigenerational living. As a young adult, I always stated that I intended to live separately with my own family after marriage. However, my relatives would respond that my living conditions might not be entirely up to me. They would ask what I would do if my in-laws needed care, why I would pass up on the opportunity to have in-laws — resident babysitters — and how I had considered finances. All these factors need to be taken into account.

In Armenia, new families often start in a multigenerational living arrangement with the intention of eventually moving out.

The family model is influenced by various factors. These include social and cultural changes like the growth of the urban population, an increase in highly educated women, and the state of the economy that impact the family model. Government policies have also played a role in allowing nuclear family living to coexist with multigenerational homes in Armenia.

The term “nuclear family” was first introduced in 1926 to describe a family comprising a married couple and their children.

According to Marxist economic theory, the establishment of capitalism led to the creation of the nuclear family, which contrasts with the evolutionary explanation of the multigenerational family. This theory positions the nuclear family as a vehicle for introducing and establishing new societal norms, and for transferring capital between generations.

During the 1950s, the nuclear family consisting of a father, mother and two children, was considered the all American family model. This ideal was featured in movies, literature and television.

However, in modern western societies, the nuclear family is no longer the predominant form. Starting from the 1970s, “alternative or the variant” family structures expanded the conventional understanding of family.[1] These include families headed by a single parent, unmarried couples, same-sex couples, and even multigenerational households.

Similarly, the family structure in Armenia has undergone its own evolution. Until halfway into the last century, the traditional family in Armenia typically consisted of 10-15 members. According to a 1970 census, the average Armenian family was made up of five members. By 1989, the average was 4.7 members, which further reduced to 4.11 in 2001 and 3.92 in 2011.[2]

While the nuclear family in Armenia is often associated with more recent times, it actually became more prominent during the industrial development and rapid urbanization of the Soviet era. The alternative family structure also emerged in Armenia, but not in the contemporary sense of the family free from traditional institutional formulas. Instead, it arose due to the 1988 Spitak earthquake, immigration, the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, and the 2020 Artsakh War. These events contributed to the increase in single-parent households.

Labor migration, particularly in rural communities, has also influenced family structures. Often, the father is absent due to work, leaving the mother to manage the household and the children.[2] These factors, along with cultural shifts and government policies, have significantly impacted the family structure in the country.

New Family, New House?

When governments invest in long-term planning, their goal is often to support and develop a society that can effectively meet the needs of the state. Subsidized government programs aimed at helping young families acquire homes can significantly influence models of family living. For example, smaller housing units provided to young families can reduce the likelihood of multigenerational living.

Buildings better known as “Khrushovkas” were commissioned by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushov in the 1960s. These are three to four-story concrete structures with an average living space of 30-60 square meters per apartment, designed for small families. Although they were intended to be a temporary solution to the needs of the day, many are still in use in a number of neighborhoods of Yerevan and other post-Soviet cities. Perhaps not intentionally, but certainly by their continued existence, they have contributed to nuclear family living.

The State Program for Affordable Housing for Young Families in Armenia, which started back in 2010, illustrates the impact of policy on family living arrangements. The program’s justification indicates that it was launched when it became clear that most young families couldn’t afford to buy their first home. It also reveals that 46% of married couples would like to get a mortgage to buy an apartment, but high interest rates and mistrust in the banking system discourage them. On the other hand, 90% of young people in the country, given other prerequisites, see owning an apartment as a prerequisite for starting a family. To qualify for the program, the combined age of the couple should not exceed 60, and neither partner should be older than 35.

One initiative, the Income Tax Refund program, allows Armenian citizens to purchase apartments directly from developers for no more than 55 million AMD. It offers a refund of mortgage interest rates from the beneficiary’s income tax fund. By the end of 2023, the program had 38,911 beneficiaries, and from 2018 to 2023, 132,042 units of real estate were built.

While these two state initiatives may primarily aim to stimulate construction and therefore the economy, several factors such as the age criteria and the cap on the available sum, coupled with current real estate market prices, suggest that they will indirectly boost the numbers of nuclear families.

“How Unbecoming of You”

At 34 years old, Marine Ghazaryan has lived with her in-laws for 13 years. She realized shortly after marrying that they would need to move out, despite her in-laws’ house being large and comfortable. She found that regardless of their good relationship, intergenerational differences were inevitable.

Her reasons for not moving out were cultural and financial. “It was a persistent discussion with my husband. He initially opposed the idea, unable to understand why we should leave a spacious house and his parents,” Ghazaryan recalls. The financial considerations, like the necessary down payment and high loan interest rates, were also a deterrent.

Over time, societal changes influenced their decision. Ghazaryan was initially the only one who felt her nuclear family should move out. However, she noticed that her mother-in-laws’ friends’ children were marrying and choosing not to live with their parents. This made her mother-in-law reconsider the benefits of their independence.

Societal pressure to stay with the parents remained, even after they moved out. Relatives lamented, “How unbecoming of you.”

Eventually, the couple applied for the Tax Refund program and bought a house in a new development, not far from the parents’ house. They were able to create their own space and time alone, while still being available to support the parents and receive help in raising their children.

Studies Have Not Shown

Throughout my life, I’ve been told that the ideal path for young people, especially women, is moving from their parents’ house to their in-laws’. The response to my contant curiosity about living alone or with the person of my choice has consistently been: never. The Youth Study Armenia (In)Dependence Generation report reveals that 26% of 14-29 year olds in Armenia are completely financially dependent on their parents, and 17% rely on financial assistance from them. In rural communities, young people are financially more dependent on their parents than their urban counterparts.

However, even when financially independent, young couples still face cultural and social barriers that delay their desire to live separately from the older generation after marriage.

Contrary to the common belief that Western culture’s influence on Armenian society is causing the traditional Armenian multigenerational family to break down, several economic, demographic, political, and natural factors have continuously impacted the family structure in Armenia. The multigenerational family model, often generalized as the traditional Armenian family, is not unique to Armenia. It’s been the predominant model in various societies at different times, helping overcome the challenges of each era.

Living separately before and after marriage is no longer a far-fetched notion. Today, it’s becoming the reality for many people around me. The challenges facing today’s society are different, and so are their priorities. Modern societies are noticeably more complex and diverse. These changes are not inherently positive or negative; they’re simply facts.

Footnotes:

[1] Betty E. Cogswell, “Variant Family Forms and Life Styles: Rejection of the Traditional Nuclear Family”, The Family Coordinator (1975)

[2] Pogosyan G., “Armenian family. Between tradition and modernity” (2021), Issue 10 C. 106-115

Raw & Unfiltered

Transgression Object: How A Nice Mormon Boy Made a Lot of Azerbaijani Enemies

A personal account by Alexander Thatcher of what it means to be targeted and attacked by Azerbaijani trolls, a kind of harassment made possible because of the ambiguity afforded by anonymity.

Read moreDeciding to Untie the Knot: Divorce Rates on the Rise

Over the past decade, the number of marriages in Armenia has been decreasing, while divorces are on the rise. Gohar Abrahamyan looks at the psychological, social and financial implications of deciding to untie the knot.

Read moreThe Crossing: Armenians Arriving in Los Angeles via Mexico

There has been a dramatic increase in the number of Armenian nationals crossing the U.S.-Mexico border following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War. This trend speaks to the urgency and desperation of those leaving a country plagued by conflict. Maral Tavitian’s investigation.

Read moreWhat Role Can Armenia Play in the Defense of Minorities in the Near East?

For over a decade, there have been attempts by the conservative and even the extreme right to protect Near Eastern Christians and other Eastern minorities, which all too often does a disservice to the cause of the very populations they claim to defend.

Read moreDiscussing Waste and Trauma

While there is enough food produced in the world to feed everyone, almost one third of all food produced globally is lost or wasted. With an almost 30% poverty rate, the issue of food waste in Armenia should become part of the public discourse.

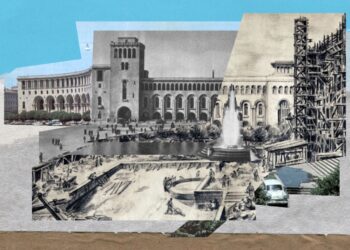

Read moreBetween Ownership and Neglect, Part 1: MFA Building

In the first of a series of articles about privatized and abandoned historic buildings in Armenia’s capital, Hovhannes Nazaretyan looks at the privatization process and current condition of the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs building in Yerevan’s Republic Square.

Read moreBetween Ownership and Neglect, Part 2: Aram’s House

The home of Aram Manukyan, widely recognized as the founder of the First Armenian Republic, located on 9 Aram Street in downtown Yerevan, continues to be abandoned and dilapidated and its future uncertain.

Read more