Over 100 years ago, my maternal grandmother’s entire family was massacred in the city of Van, situated on the southeastern shore of the eponymous lake in present-day eastern Turkey. This May, just over 108 years after the start of the Armenian Genocide – which systematically destroyed the Armenian nation within the Ottoman Empire and left 1.5 million Armenians dead throughout the First World War – I visited the beautiful city on the lake where echoes of its Armenian past still remain visible; and where my great-grandmother was the lone survivor of her extended family.

Having spent months living between Yerevan, Armenia and Tbilisi, Georgia, I joined a dear friend living in Tbilisi for a four-day road trip through eastern Turkey days before one of the most consequential elections in that country’s history.

Our journey started with a five-hour train ride from Tbilisi to the picturesque Georgian port city of Batumi on the Black Sea in the Adjara region. At the Sarpi border crossing, a 30-minute taxi-ride from Batumi, we crossed into Turkey and met up with Murat, our car rental agent, waiting for us at the mosque a few hundred feet from the border station. Our journey through Turkey started in our 2023 white Renault Clio rental.

Traveling toward the city of Van (Armenian: Վան; Kurdish: Wan), our ultimate destination, we followed the D010 highway. We made a quick stop in the quaint city of Artvin – the “pearl” of Turkey’s Black Sea region” – tucked deep into the valley where the Çoruh River flows through the Kaçkar, Karçal and Yalnızçam mountains, before continuing on to the ancient city of Kars (Armenian: Կարս or Ղարս; Kurdish: Qers).

The road to Kars was a majestic blend of scenery, encapsulating the landscapes of multiple continents. Having already passed through the dry hills covering the Çoruh river and its many dams, the road towards Kars snaked into hillsides, dotted with small cottages. The drive through winding mountain roads, canopied with tall trees and breathtaking views, stretched into the horizon.

By nightfall we were near the 22,000 populated historic city of Ardahan (Georgian: არტაანი, Armenian: Արդահան, Kurdish: Erdêxan). Our Clio’s headlights lit the flat land, speckled with melting snow – the air was covered by an ominous mist. Once in Kars, the air opened up, revealing a city shrouded by a dark night sky with sparkles of light from illuminated small cafes, bars, and a few restaurants in the city center.

The over 90,000 populated modern city of Kars is remembered by Armenians as the ancient capital in the 10th century of the Bagratid Kingdom, a polity which covered much of the “Armenian plateau”. The ancient fortress of Kars still sits high above the city granting a commanding view stretching for miles in all directions. Nearby, in an eye shot of the border with the Republic of Armenia, lies medieval ruins of the famed city of Ani nestled by the Akhurian River between the Armenian and Turkish border. Noted for its grandeur, Ani was a wealthy metropolis, and a key point along the Silk Road and other trade routes. Over a thousand years ago, the Cathedral of Ani was home to the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church, and Ani was nicknamed the “City of 1001 Churches” – as Armenians still refer to the city (an exaggeration, but a symbolic one nonetheless for the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion in 301 AD).

Following countless cycles of conquest by differing ethnic groups and empires, by the 1700s Ani was completely abandoned. Today, as a world heritage archaeological site, the dark pink volcanic basalt tufa stone constructed ruins of the cathedrals are testament to the religious architectural prowess of the medieval Armenians. While the region passed hands and eventually ended under Turkic control throughout the following centuries, it prominently remains in the Armenian national memory.

In Kars, as in all the cities we visited, we were treated to the hospitality noted in the broader region. Even though the majority of our interactions required extensive use of our mobile translators, the warmth and kindness of every person we encountered felt familial. Our breakfast feast could feed an entire family – served, of course, with an endless supply of warm, dark tea (Chay). The spread of fruits, vegetables, breads, dips, and eggs brought back memories of the Sunday brunches I helped make with my parents back in the U.S. and similar to those I occasionally treated myself to while living in Yerevan.

Departing Kars for Van, we drove towards the ancient, open air museum of the city of Ani, under a light rain. Our arrival coincided with a heavy downpour – dashing from our car to the tourist ticket office left us completely soaked. After spending a few minutes admiring the ruins of Ani from afar, and with the rain persisting, we decided to get a headstart on our five-hour drive to the city of Van. I will most definitely return to Ani soon – hopefully on a sunnier day.

The route to Van revealed a different scenery than the previous day. Skirting by the ancient Ararat mountain standing at over 5,000m/16,000ft, another geographic symbol of the region which I had admired from across the border in Armenia, I now had full views of Ağrı Dağı (mountain of sorrow in Turkish) with its two dormant volcanic snow-capped peaks. Located entirely in Turkey, Ararat’s wider region is said to be where Noah landed his ark following the devastating floods recounted in the Old Testament. For Armenians viewing the mountain from across the (closed) border, Ararat is a reminder of historical traumas and the present realities.

In the southeast of Turkey we drove along the Iranian border. As Turkey is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) only border with the Islamic Republic of Iran, the well-guarded hillsides are dotted with countless guard posts and armed guards, bearing Turkish and Iranian flags. The road to Van circled a portion of the eponymous lake and its sun-drenched, shimmering blue waters – focusing on the road with the breathtaking view was challenging. We pulled over by a small sandy beach to admire the full landscape. I decided that the next day I would take a dip into the clear waters of Lake Van in memory of my great-grandparents.

That night’s dinner in Van was once again an unexpected feast fit for a tribe – we were treated to table ladened fresh herbs, deliciously aromatic salads and vegetables, and specialties of the region. After dinner we stopped by one of the countless bakeries lining the main boulevards to satisfy my sweet tooth, which has feasted on many baklavas over the years – but never a homemade Turkish version. Whether due to my tiredness, or sheer incompetence, the price the pastry seller gave astounded me. “10 dollars for a small piece of baklava, that’s outrageous,” I thought to myself, and made my dissatisfaction known through hand gestures as I walked away.

A few minutes later, I realized I had wrongly converted the price to Georgian Lari instead of Turkish Lira. The kind baker – whose confusion at my reaction was outwardly visible – asked for 28 Turkish Lira ($1.07!) – which I registered as 28 Georgian Lari ($10.79). Needless to say, out of sheer embarrassment I did not return to the bakery that night – and decided to fulfill my sweet cravings another time.

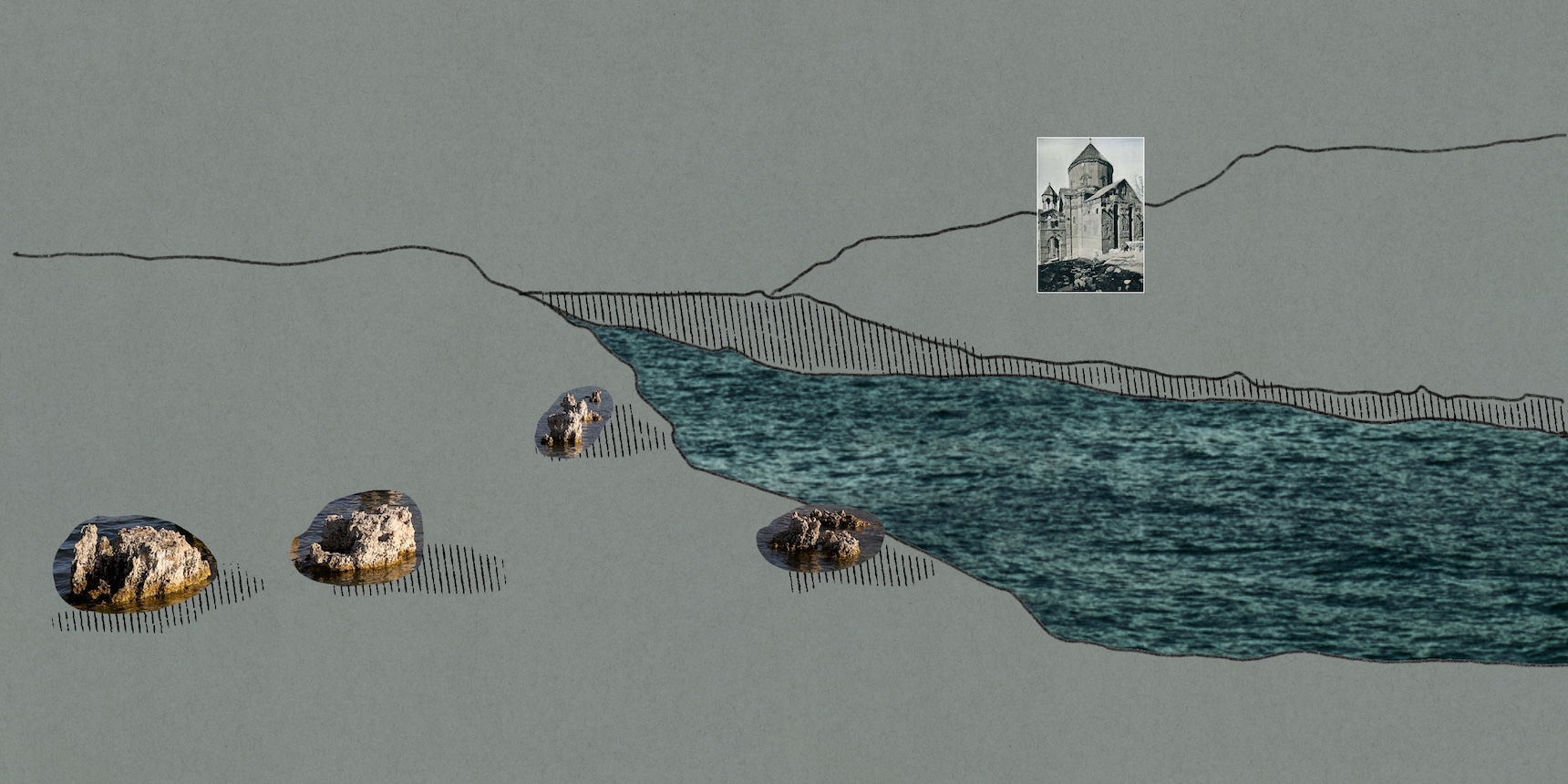

The following morning, after indulging in a humble “Turkish breakfast for two” we drove west along the lake towards the town of Gevaş to charter a small ferry to the ancient Akhtamar Island, the second largest of the four islands on Lake Van and where my great grandmother was married. The island is home to the 10th Century Holy Cross Cathedral, built under the Armenian King Gagik 1 of the Artsruni dynasty which ruled the Kingdom of Vaspurakan. The national poet of Armenia, Hovhannes Tumanyan’s poem Akhtamar makes for an easy read while aboard the 15-minute ride to the island and tells the legend of a love affair. The Cathedral, having endured degradation and vandalism in the early years of the Turkish Republic, has since been revitalized as a UNESCO site. While critics may point to the Turkification of the island and the church, I was grateful to visit and embrace the remnants of an Armenian past still (mostly) preserved.

Instead of spending a second day in Van, we got a head start on our 10-hour drive back to the Turkish border city of Hopa, to return our car and head back to Batumi. We embarked northwards on a five-hour drive to another ancient city: Erzurum. Following the partition of eastern Anatolia between the Byzantine and Sassanid (Persian) empires in the 4th century, the city, renamed to Theodosiopolis, became a fortified outpost along the contentious new border. By the 13th century, it fell to Seljuk Turkic rule who built the breathtaking Twin Minaret Madrasa, which became an institution for Islamic education. Still intact today, it showcases Islamic artwork and scripture tucked away within chambers throughout the main atrium.

Once back in Hopa, following a five-hour long rain-covered route along an endless stream of tunnels through the mountain edges, we met up with Murat, who drove us back to the Turkish border crossing at Sarpi. A long caravan of cars, vans and buses were decked out in political advertisements, flags, and, of course, music on the opposite side of the road. Murat talked to us in Turkish about Sunday’s elections. I asked who he supports. In Turkish he responded, “CHP” and in English he confirmed “Not Erdogan. On Sunday, May 14 2023, as neither incumbent Erdogan nor his challenger Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu reached the threshold needed to secure an outright victory, the second round was scheduled in two weeks time. Erdogan went on to win the election on May 28 and extend his two-decade rule over Turkey.

Also see

Magazine Issue N12

Tastes and Memory

Food is a repository of our most cherished memories. It connects us through time and space and memory unlocking the keys to our heritage. It carries us back to our childhood. To large family dinners, of tables overflowing at Christmas, Easter, birthdays. It binds us to the lands that we are no longer the masters of. Recipes carried across cities and deserts and continents, handed down from one generation to another are vessels of a family’s traditions and customs even when they are altered, adapted and molded to new realities. This month’s issue entitled “Tastes and Memory” is not simply about food or recipes, it’s about identity and the stories that are woven into the fabric of our collective memory.

Artin DerSimonian’s essay is one of the saddest descriptions of the goals and dreams of a member of the Armenian Diaspora. Artin admits that his family was from Van and that the family was butchered in Van. He doesn’t give the names of his ancestors and he fails to identify the perpetrators, were they Ottoman soldiers? Sunni Turkish civilians? Kurdish tribesmen? Artin states that his family was killed within the city of Van. Maybe the Turkish military killed his family during massacres in Van in April-May of 1915. . .There is a “don’t ask, don’t tell” aspect to the narrator’s interaction with Turks and Kurds in Van. Do the locals admit the crimes of their ancestors? Did they know that he, Artin, was an Armenian by way of Scotland, and that Artin’s very own great-grand parents were born in, and on, that land? Artin states that the Turks and/or Kurds were hospitable and friendly, but did these hosts know that he was a great-grand son of that land? The essay just discusses this or that beautiful lake, mountain, some good food. . .Jewish people can go visit the Death Camp at Auschwitz were their ancestors were murdered. It’s a dark pilgrimage, a solemn one. Our Armenian ancestors’ bones are scattered on across the places Artin visited. When we visit Van, are we to simply have a sumptuous Turkish meal and ignore the fact that the locals live in the open-air cemetery of our ancestors? We, Armenians, are allowed to visit Van because there are no “open” Armenians there (there are “Hidden” Armenians, but this essay doesn’t seek to find them), but right now we can’t visit Stepanakert, because there are still Armenians there?

Western Armenia is a crime scene, and we have not received even a modicum of justice.