Listen to the article.

The village center in Voskepar was full of people despite the dark clouds in the sky and the gloomy weather. People were gathered in small groups, standing mainly in silence. A film crew from France was trying to convince the mayor to give an interview, he was resisting.

Following Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s visit to Voskepar on March 18, the villagers are unsettled.

The Prime Minister had come with what residents say is “very bad news.” The demarcation and the delimitation process between Armenia and Azerbaijan was entering its implementation phase, and it was going to start from Tavush.

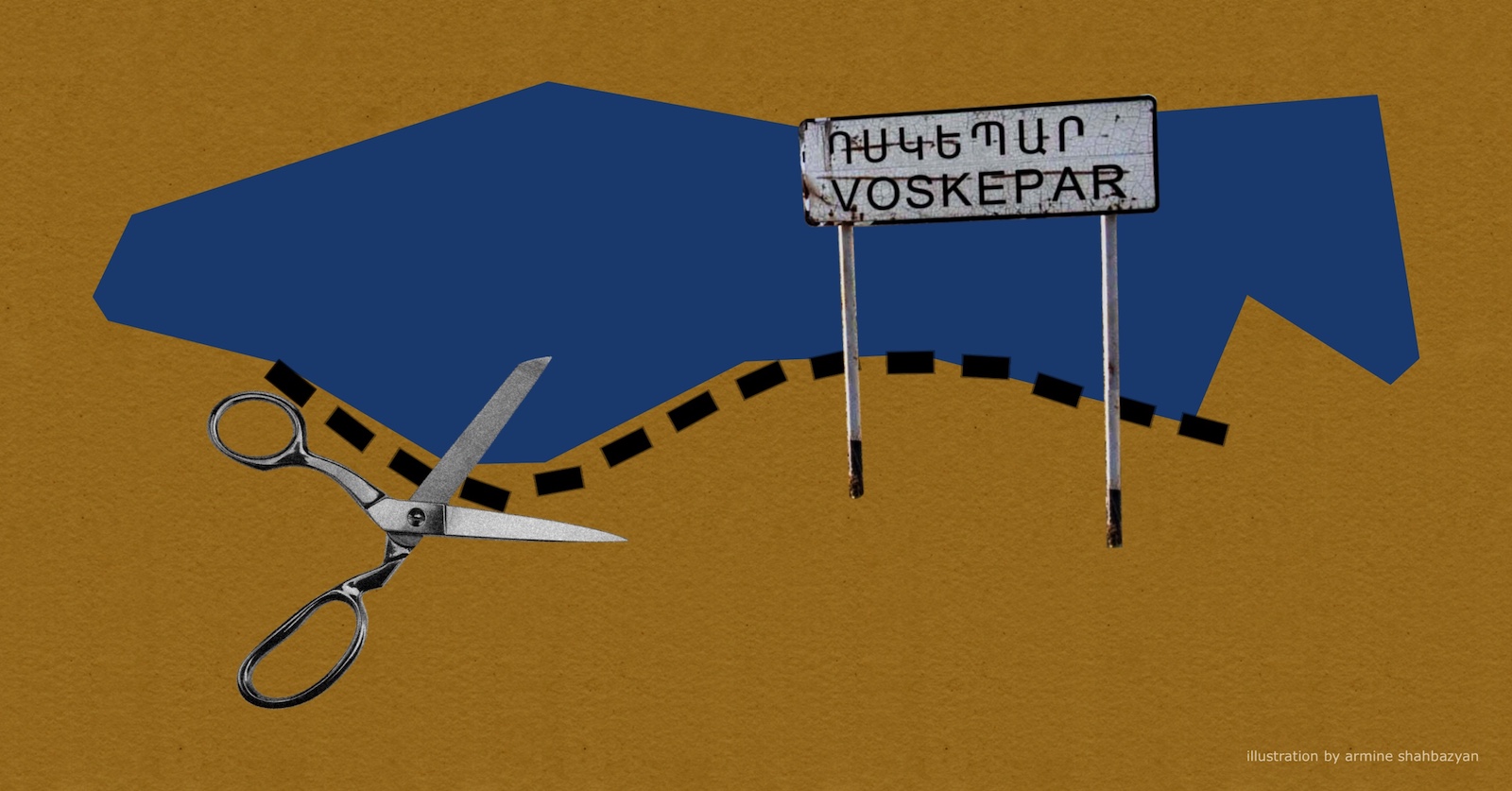

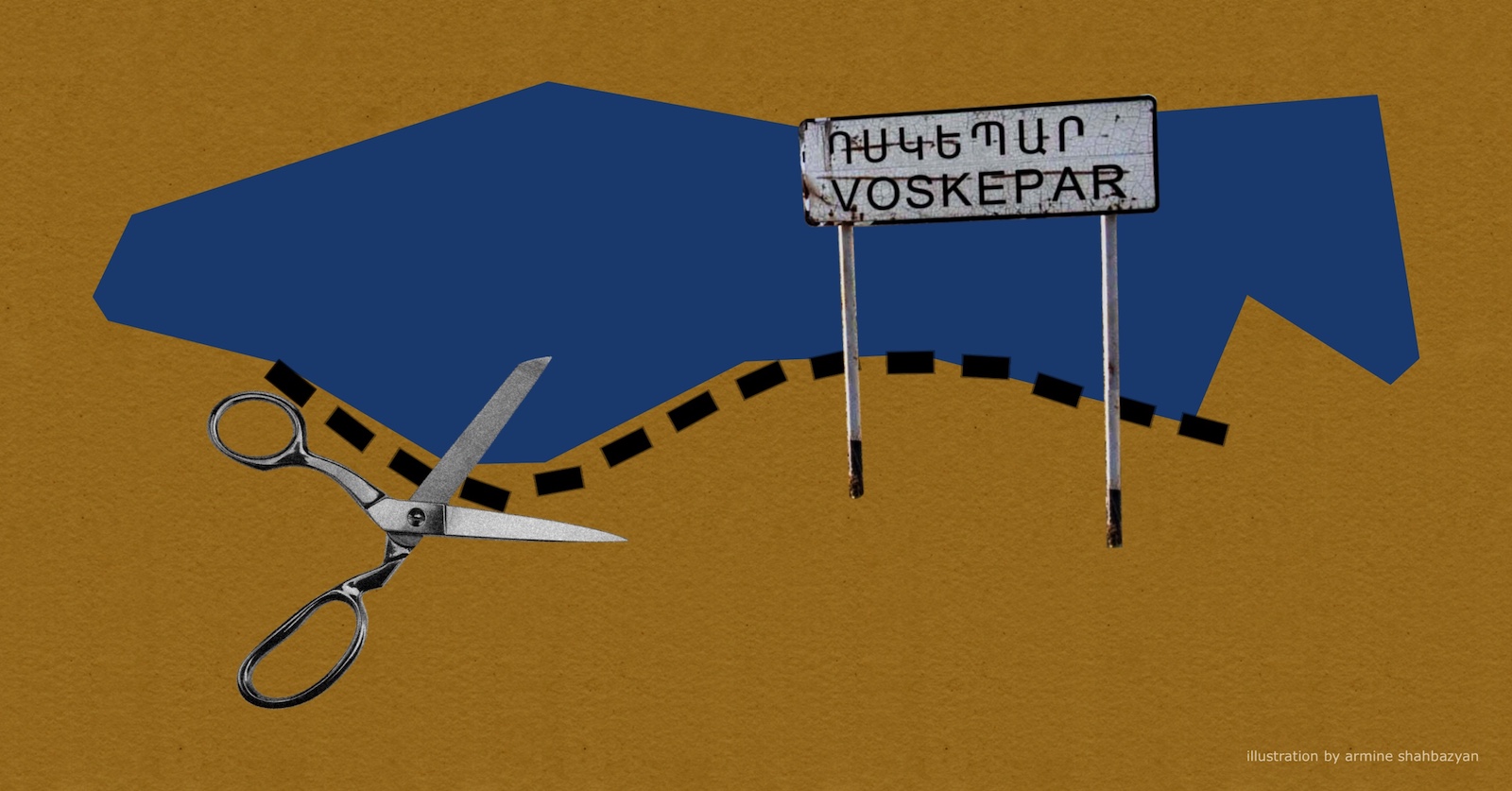

Official Baku has demanded the immediate return of four villages in the Gazakh (Qazax) region, located immediately across the border in Tavush: Baghanis Ayrim, Ashaghi/Lower Askipara, Kheyrimli, and Gizilhajili. As per the Alma Ata Declaration, these four villages are not de jure in Armenia’s territory. “There have never been villages with such names in Armenia,” the Prime Minister had said as consolation.

These villages came under Armenian control in the early 1990s during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. The interstate road to Georgia and the gas pipeline entering Armenia are nearby.

March 23: 4 p.m.

“Are you from Voskepar?” I asked, approaching a group of people standing in the center of the village.

“Absolutely!” responded one of the men in the group, sharply accentuating the first vowel of the first syllable as if trying to compress several meanings in one word while shutting down my attempts of initiating a more elaborate conversation.

“I’ve spoken plenty, I’ve answered so many of these questions that my head feels like a pumpkin. That man there in red, he is a teacher, you can talk to him.”

My interlocutor readily introduced himself.

“I am the headmaster of Voskepar secondary school military education, a historian by profession. Beglaryan, Nver.”

When Prime Minister Pashinyan went to Tavush, he said that more than likely, the demarcation and delimitation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan state border would begin in Tavush, specifically the Baghanis-Berkaber section, stressing that their objective is to prevent war. “We are doing this not only for Armenia but also for the village of Voskepar, for the village of Kirants, to guarantee the safety of these villages,” he had said.

If the return of these four villages would benefit the safety of Voskepar, then why are the villagers so concerned, I asked.

Beglaryan responded on behalf of the village: “Everyone in Voskepar and the region are against this decision. We give the land, that means we allow the Turk [Azerbaijani, Ed.] to come and stand on our head. The people understand the repercussions. First of all, we will lose access to the Armenia-Georgia road, secondly we lose the Yerevan-Syunik road near Tigranashen, near Azatamut, we will lose the connection to Berd, Vazashen … the Azerbaijanis simply want control over Armenia’s highways. By moving forward and positioning themselves above Voskepar, they will eventually take the village and the population of Voskepar will emigrate. This is not only my ancestral village but it is also a stronghold connecting Ijevan and Noyemberyan. If there is no Voskepar, then Noyemberyan, Ijevan, Vanadzor and Gyumri are wide open. The people have said their decisive ‘No.’”

But the justification is that these four villages in question were never part of Armenia’s official border, they were Azerbaijan’s.

“They were theirs, now they are ours. We should not return them because there is international law… When those villages were neutralized at the beginning of 1990s, they were already not villages, the population had left. At that point, they were military bases. The neutralization of military bases is recognized by international law. The Armenian army did just that to insure that our population can continue living in the region.”

I approached another group.

“Are you from Voskepar?”

“We are, yes but have nothing new to say, we have been talking for days now. But if you approach the man with the white hair, he will definitely be willing to talk,” one of them said.

Indeed, the white haired man readily responded to my request to talk but refused to give me his name.

“No offense, but many like you come, ask people questions, get their answers and then turn them around, there are some games at play.”

How likely is it that the people of Voskepar will emigrate after the handover of these four villages?

“Emigration will be natural, it will happen if they proceed with the map the Azerbaijanis are proposing. People immigrated even after Voskepar took self-defense measures in the 1990s. To date, half of the villages are immigrants somewhere else, can you imagine what it will look like if the Turk directly has eyes on us? We could say we will not move, but what would be the point of lying?”

According to a recent census, as of January 1, 2023, there were 721 people living in Voskepar.

I ask the group what they think of the opinion that the villagers here should be armed.

“There is no need to arm the people, they should simply understand that this should not be an option, it is not a viable solution. After having been through all that we have been through, how can the Turk be trusted to take over our current positions, which give-or-take are good positions, and still keep the peace. Is that even possible?”

The Prime Minister said, if we refuse, there would be war within the week.

“War… first of all, that was not the right word to use. Azerbaijan tried war once in these territories in the 1990s and what was the result? They lost territories, they lost these villages. There is no need to scare the people, break their spirit. But also, let no one declare themselves heroes, boast of being ready to do this or that… still, no need to speak to the people in that language.”

Do you think peace and peaceful coexistence is possible?

“We are pro-peace. There was a time when we had normal relations. I might have believed it would still be possible before the 44 Day War. We need peace but having seen what we have, there is no trusting the Turk, after all the likely and the unlikely things have already happened.”

Someone else joined the conversation.

“There was a time when we would attend each other’s weddings, Armenians and Azerbaijanis…now the borders are set in a way, we did not realize this at the time, that the situation between the two countries could be manipulated to escalate at any given time. We know what war is but one-sided concessions are not the way to go either. We are not pro-war. They are openly against peace. In this case, it is not possible to find common ground with them.”

People from Voskepar point to the areas that are to be given to Azerbaijan and make it clear that the outcome will be that Voskepar itself will consequently become somewhat of an enclave inside Azerbaijan. Our new interlocutor continues.

“So, we were defeated in 2020, this does not mean that we will have to stay defeated, constantly offer concessions. Our defeat does not mean the Turks can do whatever they want. I’m not even in the mood to talk. We give those villages, it means Voskepar will be in a ring, I’m not optimistic. Our positions here are ok, they are not bad. Ijevan is the regional center and we have to head there for every little thing. Imagine if we had to go all the way to Kirovakan [Vanadzor] to then reach Ijevan.”

The people gathered at the village square were mainly men and one of them pointed out: “Women have no business coming and standing in the village square. We have our customs. For example, you’ll never see the youth hanging out here with bottles of beer. That is not something acceptable here. We try to keep everything here within limits.”

As the man concluded his sentence, I noticed two women on the road. I tried to reach out to them but the man stopped me.

“Where are you going? That is my wife, Hamest. Hamest! … Hamest wait, it is time to milk the cows, we need to go.”

The woman smiled from a distance in confirmation of her husband’s words, making it clear that she had work to do, had no time to chit-chat at the village square.

Is there a wedding venue in Voskepar? My question made the white haired man frown.

“Eh…we do have a hall for celebrations but as fate has it, more often than not, it serves as a funeral home. Weddings are rare. Even when there is one, usually they do it somewhere outside the village.”

There were two half-constructed structures next to the municipality. I was told that the owners decided not to finish building, that there was no point to it, they are not even there, they live in Russia.

Then I noticed a woman in the adjacent house, she was sweeping the yard.

“Good evening.”

She looked in my direction, and continued to sweep without replying.

“Would you mind if we talked?”

“I don’t want to, I’m not in the mood to talk.”

It was getting dark, people were still standing at the village square, no one was ready to leave.

Also see

Enclaves Enter Armenia-Azerbaijan Peace Talks

The issue of tiny but strategically placed Soviet-era enclaves in Armenia and Azerbaijan has come to the forefront of peace talks in recent months. Hovhannes Nazaretyan maps it out.

Read moreThe New Home the Men of Artsakh Built

After being forcibly displaced by Azerbaijan, a group of men from Artsakh transformed the interior of a dilapidated hospital in the Ararat region of Armenia and built eight separate apartments for their families. A photo story by Ani Gevorgyan.

Read moreMonologues: The Homes They Lost in Artsakh

“The story of the house began with a smile and ended with tears,” writes Yan Shenkman, a Russian journalist, who moved to Armenia after the war in Ukraine started. He compiled monologues from the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh for an upcoming exhibition about the homes they lost.

Read moreWe’re Home, And Yet We’re Not

In September, two families-in-law from Artsakh found refuge in the village of Yeghvard, Armenia, joining over 100,000 displaced Armenians facing similar challenges. Marut Vanyan, a journalist from Artsakh, provides insight into their experiences.

Read moreThe Now of Literature, After the War

How does war shape the collective narrative? How have Armenian writers since the 1990s approached the impact of multiple wars? Mariam Aloyan looks at Armenian “war literature” spanning generations and decades.

Read more