Life is a fairy tale made up of two parts: the years of the Artsakh war and the years following it. This is how Colonel Aida Serobyan, who was called dokhtur (doctor) on the battlefield, looks back at her journey. Aida went to Artsakh with the intention of staying for two months, but ended up staying for two years up until the end of the war. During those years, she was injured four times and took part in the liberation of Karvajar, Aghdam, Horadiz, Zangelan and Jabrayil, making it all the way to Minjavan, to the shores of the Arax River where she “washed her bloodsoaked hands in the river.”

When full out war began in Artsakh in 1992, Aida was 36 years old. She was working in No. 2 Polyclinic and at the same time learning first aid in the Ministry of Interior’s House of Culture. “One day when I came home from work, I saw an emergency broadcast,” she recalls. “I immediately ran to get closer to the television. They announced that medical personnel were needed in Artsakh.” After a sleepless night, the following morning, instead of going to the Polyclinic, Aida went to the Ministry of Health and asked them to send her to Artsakh for two months.

Only her colleagues at the Polyclinic knew about Aida’s decision. Her mother and three children thought she had been sent to work in one of the health centers in the spa town of Jermuk. “My mother was very happy and yet surprised that out of 340 people, I was chosen to go,” Aida says. “Fortunately, she didn’t realize that I was going to war.” Before Aida departed, her mother gave her a large cup so she could drink from the curative waters of Jermuk everyday.

Donning high heels, Aida flew to Martakert. Her family only came to know about her real destination months later. One of their neighbors, having seen Aida on television, hastened to their house to tell her family members what she had seen, however, Aida’s mother didn’t believe the neighbor and insisted that her daughter was in Jermuk. A few days later, Aida’s mother sees her daughter’s photo in a newspaper with the caption: “A lion’s cub is a lion, male or female.”

Until the creation of Artsakh’s Defense Army in September 1992, Aida was serving with the partisan brigade in the region of Martakert. When the Armed Forces was created, she moved on to serve in the Martakert regiment, and later by a decision of the Defense Ministry, she was transferred to the Artsakh Rescue Service, which had six rescue squads but no medical personnel. “It was very dangerous because the first responders were forced to remain on the battlefield, with guns in their hand,” Aida remembers. “When someone was injured, I would put down my gun and dress their wounds. If their injury was life threatening, I would personally take them to the field hospital, if not I would send them off in a vehicle so that I could continue to fight.”

Aida was among the first to be awarded with the “Mother’s Gratitude to the Courageous” medal in 1993, which was made by collected pieces of shrapnel from the bombing of Shushi. “They called and brought me from the battlefield to the theater building of Stepanakert,” Aida says. “To be honest, I was slightly frightened when they told me I had to be in Stepanakert on this hour of this day. I was scared that they were going to bring me bad news from home.”

Aida recalls that the battles were so heated that they didn’t even know when and if New Years had come to pass: “In December 1992 heavy battles were taking place in Martakert. We were fighting for days on end. All of a sudden, the battle stopped. One of the boys said, ‘Dokhtur, what day is it today?’ I said, ‘To be honest, I don’t know what day it is, nor do I know what month it is. All I know is that it is 1992.’ From a bit farther away, one of the boys called out, ‘Dokhtur, it’s been 1993 for the past five days now.’”

Impregnable Fortress and Beauty

They had to liberate the village of Kusapat which was located on a hill. Armenian forces had been forced to retreat several times and managed to maintain control over only five small villages, one of which was the village of Vank, where the monastery of Gandzasar was perched on a hill. “The Azerbaijanis had said that if they were able to capture Gandzasar, then Artsakh would cease to exist,” Aida recalls. “And we had taken an oath in Gandzasar that we would not retreat a single step from the Church. If the Azeris have to enter Gandzasar, they would have to pass over our corpses.” Aida and her comrades-in-arms made Gandzasar impregnable and were even able to move their positions forward. During the liberation of Kusapat, Monte Melkonian joined Aida and her friends with numerous tanks.

The instability and horror of the battlefield were not capable of breaking Aida’s desire to see beauty and find an imagined springtime in everything. She remembers during the years of war how enthralled she was by Artsakh’s natural beauty, and how it had managed to awaken sprouts of hope inside her: “I remember it was the end of February. The snow had melted and we were waiting for our orders to move forward. Where the snow had melted, patches of flowers covered the earth. I picked a bouquet of flowers and then the order came to push ahead. I put the flowers in the pocket of my army uniform. When we suffered our first casualty, a young man, 19-20 years of age, I took the flowers out of my pocket and placed them in the pocket of his uniform. Till now I wonder what they thought at the morgue when they saw those flowers. They probably thought that his beloved had placed them there; they would have had no idea that the person responsible was an unfamiliar doctor.”

On January 1, 1994, Aida was transferred from the Artsakh Rescue Service to the 52nd battalion of the Shushi regiment as a doctor. Later, she participated in battles for the liberation of Martakert until May 20, 1994. “We were in our positions in Avan Seysulan when one of the soldiers called out ‘Dokhtur!” I responded with “Hey!’ He yelled loudly, ‘Congratulations, the fight has ended.’”

Aida notes that at that time, seeing a woman on the battlefield was unusual. She smiles as she recalls an incident once when they had confused her with a man. “For more than a year I had no news from home,” she says. “I made the wounded comfortable and decided to go to the military post. As I was ascending, I was lost in thought. All of a sudden, I heard someone saying, ‘Uncle, uncle, will you give me a bullet?’ I turned around and saw a five-year-old girl. The child had been under the impression that only men could fight.” News about Aida began circulating so quickly that children began to not only create legends about her but that it was shameful not to know her.

She recalls another humorous story having to do with children. “One time in Stepanakert, two little boys were walking toward me and because they were talking loudly, I could hear their conversation from a distance. One was saying, ‘Listen, she is that dokhtur, who came from Armenia and is fighting with us.’ His friend, wanting to boast that he knew me well, says, ‘Yes, I know her. She is a karateka.’”

During the war, Aida and her female comrades made a solemn promise to one another that if anyone of them were to die on the battlefield, the rest would take care of her family. Today, these women continue to stay in touch. Seeing how many of them live in difficult conditions, Aida decided to establish the Organization of Women Participants of the Artsakh War so that she could help the women war veterans and their families in any way possible.

Today, Aida continues to lead this organization. She also teaches preliminary military training and first aid at the Yerevan State Humanitarian College and at the Republic of Armenia’s Armed Forces. The memories of the war years have become an inseparable part of her life and when speaking about that time, those memories are intertwined and accompanied by pride, pain and yearning.

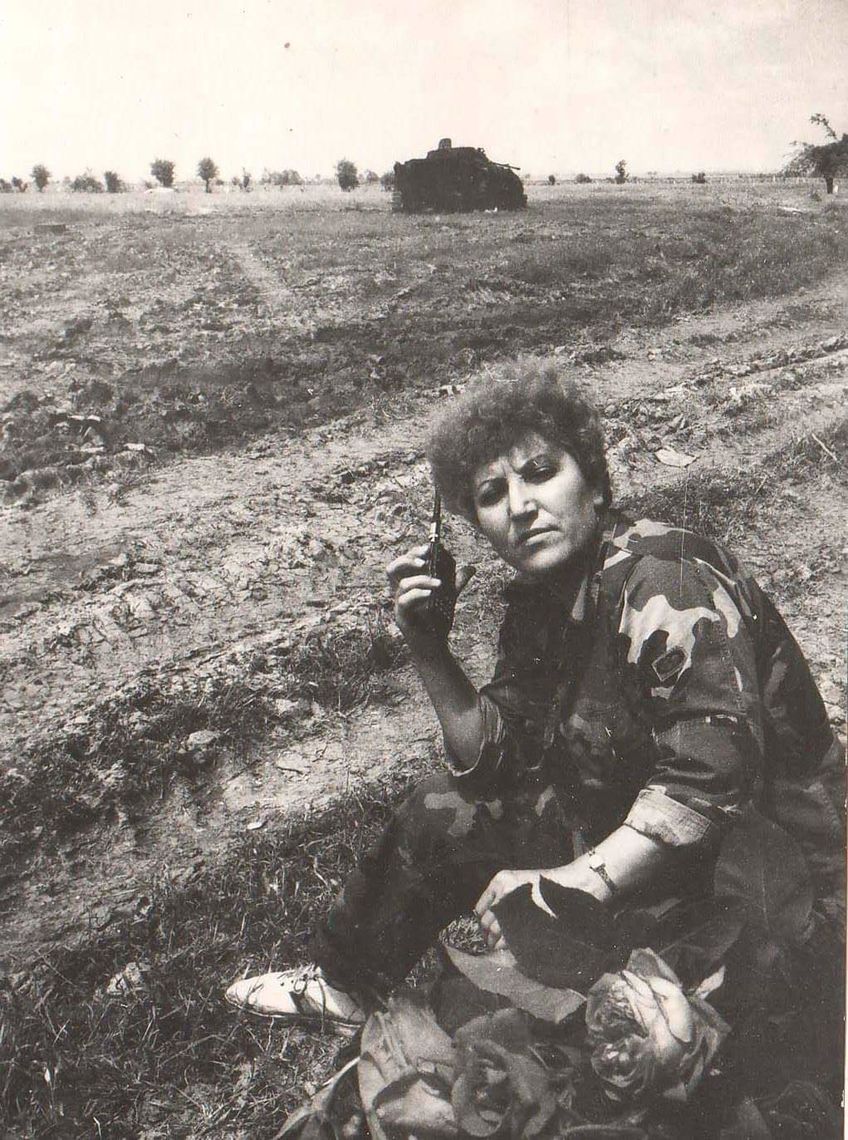

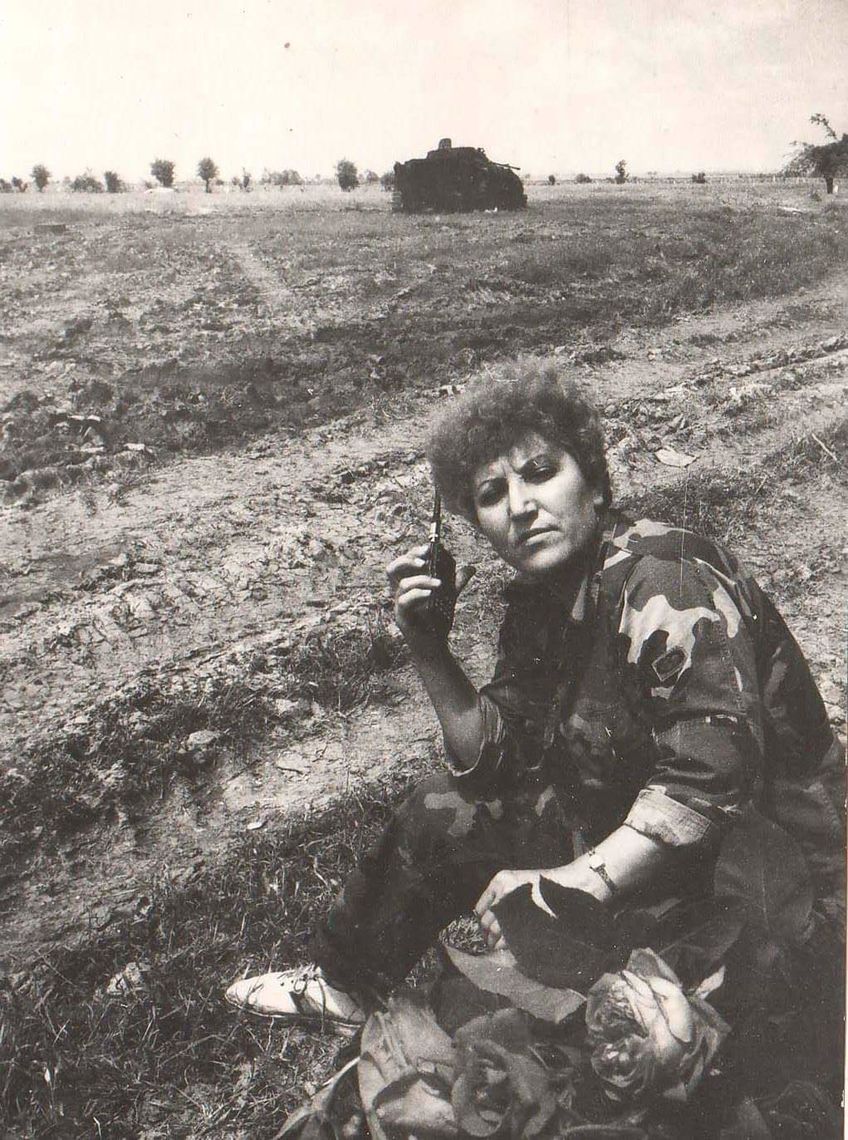

“Dokhtur” Aida Serobyan on the battlefield.

Aida Serobyan with her comrades-in-arms in Artsakh.

“A lion’s cub is a lion, male or female.”

“We had taken an oath that we would not retreat a single step from the Church.”

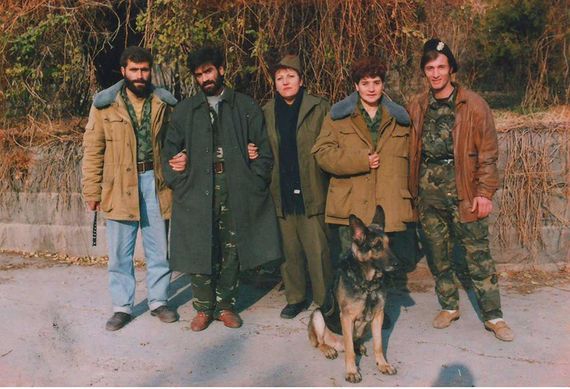

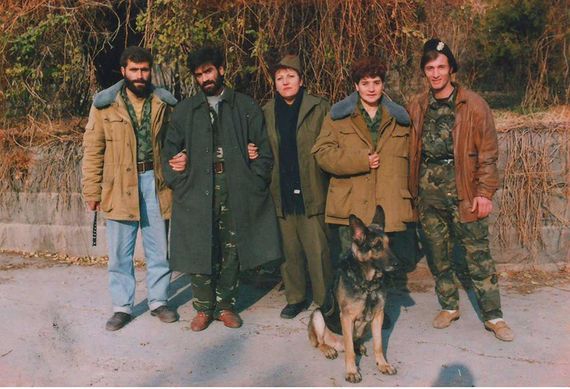

Aida Serobyan with Arayik Khandoyan (2nd from the left) and other comrades.

Aida Serobyan with Vazgen Sargsyan, Armenia’s first Defense Minister.