A week ago I received a call from Hratsin Ohanyan, a resident of Martuni and mother of four undergage children. I was silently listening to her, trying to find the words to relieve her worries as she painted a vivid picture of her family’s situation. “My youngest daughter keeps asking me for something sweet, but I can’t even get bread from the bakery anymore,” Hratsin says, explaining that if a customer owes money, the bakery will no longer give them bread. “Every night my daughter asks me if we can at least have tea with some sugar.”

Children and young people have been among the most vulnerable during the Azerbaijani-imposed blockade of Artsakh, now in its eighth month. Throughout the siege, young people had to keep up with their education — often with no gas, no electricity and sometimes on empty stomachs.

For the past few weeks, through its illegally installed checkpoint, Azerbaijan has been blocking all humanitarian aid into Artsakh, even for the Russian peacekeepers and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the only international organization operating there. According to the ICRC statement, “Despite persistent efforts, the International Committee of the Red Cross is not currently able to bring humanitarian assistance to the civilian population through the Lachin corridor or through any other routes, including Aghdam.” As of August 1, Azerbaijan is also blocking the 360 tons of emergency humanitarian aid sent by Armenia.

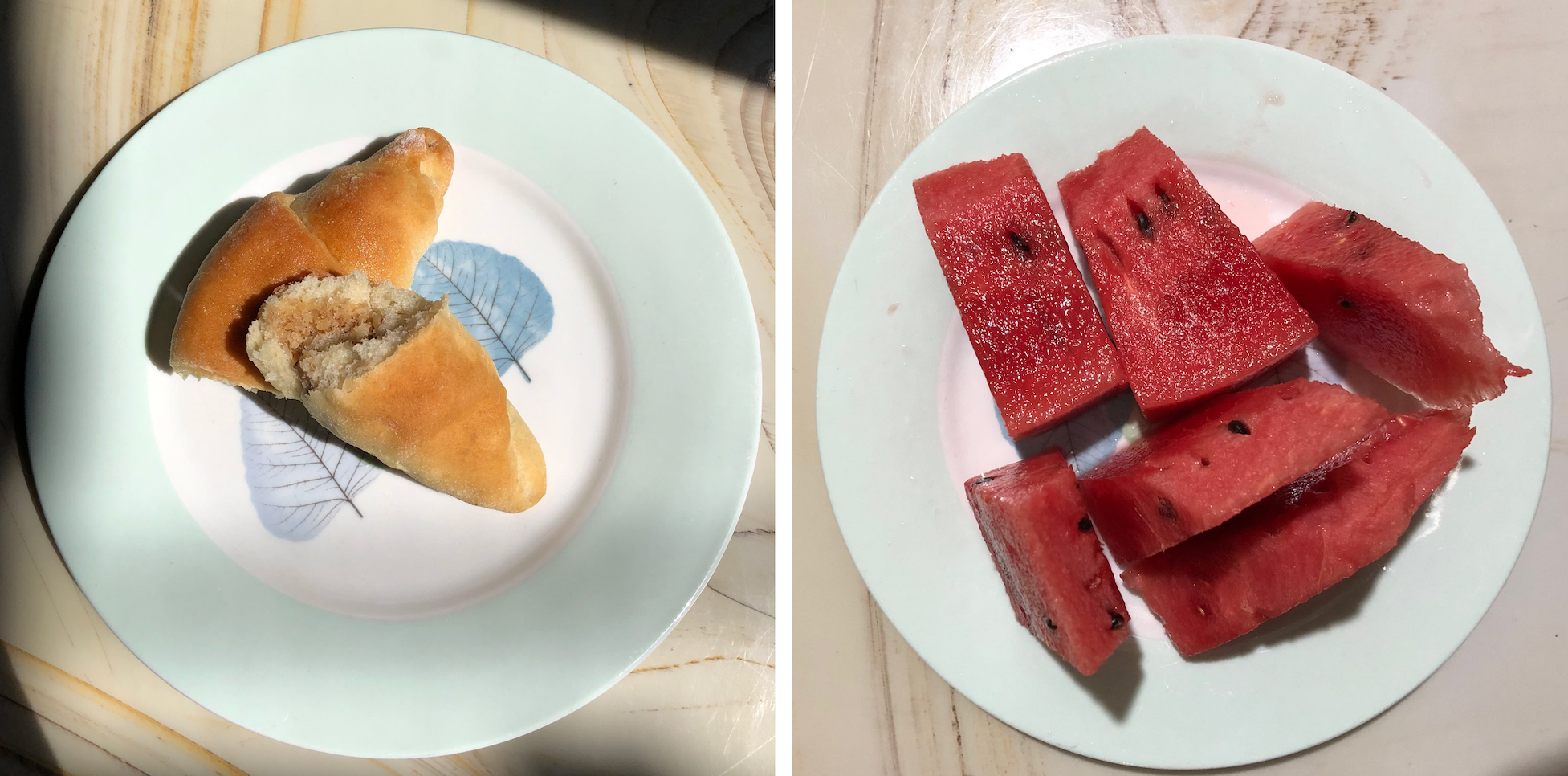

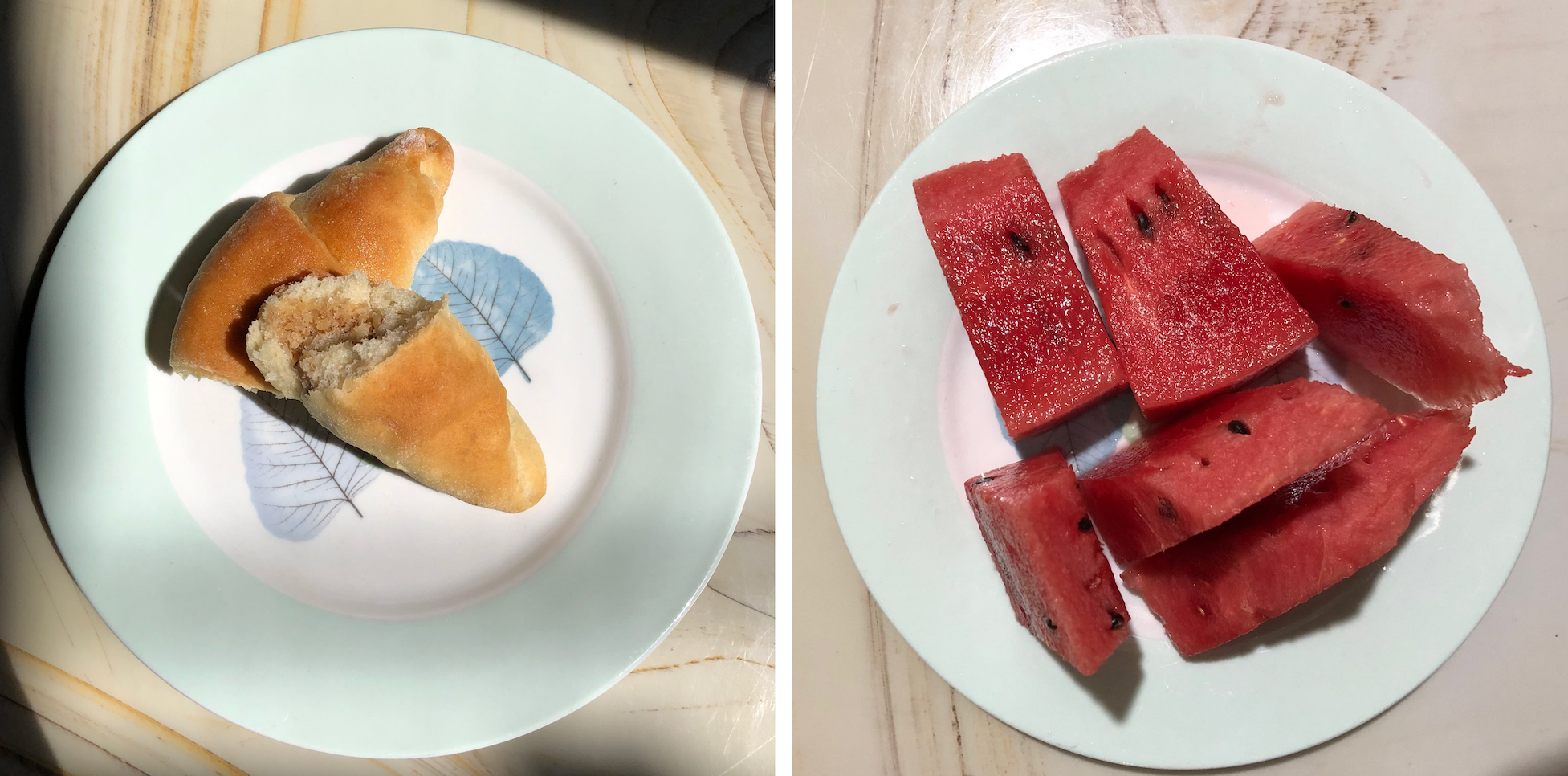

Due to the scarcity of food and energy supplies, the people of Artsakh are now facing a new wave of challenges. Amid the ongoing humanitarian crisis, young people share images of their meals and stories.

“Prior to the blockade, I used to have various options for breakfast; coffee with a biscuit or chocolate, cottage cheese with fruits or berries, something light and delicious,” recalls Raya Gasparyan, 18, from Stepanakert. While she used to have freedom to choose what to eat, finding basic necessities now feels like a miracle to her. “If you go out, you’ll see long lines of people waiting for bread for hours, in the hot sun, just to get two loaves of bread,” she says, adding that food is not the only thing hard to find; medicine, hygiene and house cleaning products are also non-existent at this point.

Raya admits that the situation is truly dire, but people are doing their best to survive. Residents in the city have turned the little flower patches in front of buildings into tiny farms. Raya says her family is lucky enough to have a little garden. “It literally saves us,” she says, noting that although the reality they live in is tough for everyone, it is especially hard for her younger siblings. “We understand the situation, bear it somehow, but it’s different with the little ones. It’s emotionally hard when a little kid asks for something delicious but you can’t find it, you can’t give something that basically doesn’t exist at all in our stores.”

“Stores being empty is an understatement; there’s a pile of dust on the shelves,” says 17-year-old Ani Balayan, a photographer with CivilNet in Artsakh. Ani has been skipping most of her meals. “There’s no street food, so I mostly don’t eat during the day and only have a meal when I get home,” she says, jokingly adding that if she were to photograph her daytime meal, it would be an empty plate. Her options for dinner are so limited that she says they have “memorized the tastes by now.” One of the foods she misses is scrambled eggs with tomatoes. “The price of tomatoes has skyrocketed and there are no eggs,” says Ani.

In the capital Stepanakert, where most people rely on produce from the market and grocery stores, fruits and vegetables have turned into a luxury. Although the Artsakh government regularly issues a cap on prices, they still remain higher compared to the prices for the same produce in Armenia. Artsakh’s State Commission on Public Services and Economic Competition regularly publishes the allowed retail price for fruits and vegetables. According to their latest report issued on July 27, the price for tomatoes, aubergines and peppers is 1000 amd/kg, for example. The most affordable fruit at the moment is watermelon; 300 amd/kg. The spike in food prices is especially challenging for low-income families, many of whom have lost their jobs due to the economic consequences of the blockade.

According to locals, the situation isn’t that dire in the villages where many people manage to get fresh produce from their own garden. “My mom manages to bake our own bread and we get most vegetables from our garden,” says 15-year-old Anna Ghazaryan from the village of Khachmach in the Askeran region. However, they still lack many essentials including hygiene products. “There are two stores in the villages; both of them are empty.”

The situation has worsened with the cessation of transportation across the country. Due to fuel shortage, all public transportation has been suspended in Stepanakert since July 18. According to Artsakh’s Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure, since July 25, all inter-city transportation has also been suspended.

“I was in Askeran with my friends when we heard the news. We panicked at first worrying how we would get back home [to Stepanakert],” 15-year-old Vera Mkrdumyan recalls. With no fuel to be found, she says they were preparing to walk all the way to Stepanakert when her friend’s brother found a battery-run car. Looking back at the start of the blockade, Vera adds, “My cousins and I have come to the conclusion that you should never complain. The more we complained the worse the situation got. Sometimes when I complain about walking for an hour in the burning sun and then waiting for a couple of more hours to get two loaves of bread, I remind myself that it could be much worse — at some point maybe we won’t even be allowed to live here, and I will be in a different place longing for these days, just to be in my city.”

While Vera tries to stay emotionally balanced, the blockade, however, has started to affect her family’s health. Her grandmother, who was taking care of the family because her parents are in Armenia unable to return home, is currently in hospital due to health issues caused by her new diet. Vera has been having digestive issues lately, as well.

The scarcity of resources caused by the blockade not only affects young people’s physical, but also mental health. “I’ve become more anxious and aggressive. I lost 4 kilograms due to stress. At the moment, it’s the other way around — I eat irregularly, and sometimes I overeat due to stress,” says Larisa Nersesyan.

With endless social media posts from her fellow Armenians showing mouth-watering foods, Larisa, like many of her peers in Artsakh, feels somewhat neglected. “Honestly, when I scroll my Instagram page, I get quite annoyed by the fact that I do not have the same life as they do. On one hand, I realize it’s normal that people go on with their lives and I have no right to judge them,” she says. “On the other hand you feel forgotten and abandoned, as if your compatriots don’t give a damn about you, and it’s very hurtful.”

Note from the author: Thanks to Diana Balughyan from Stepanakert for her assistance.

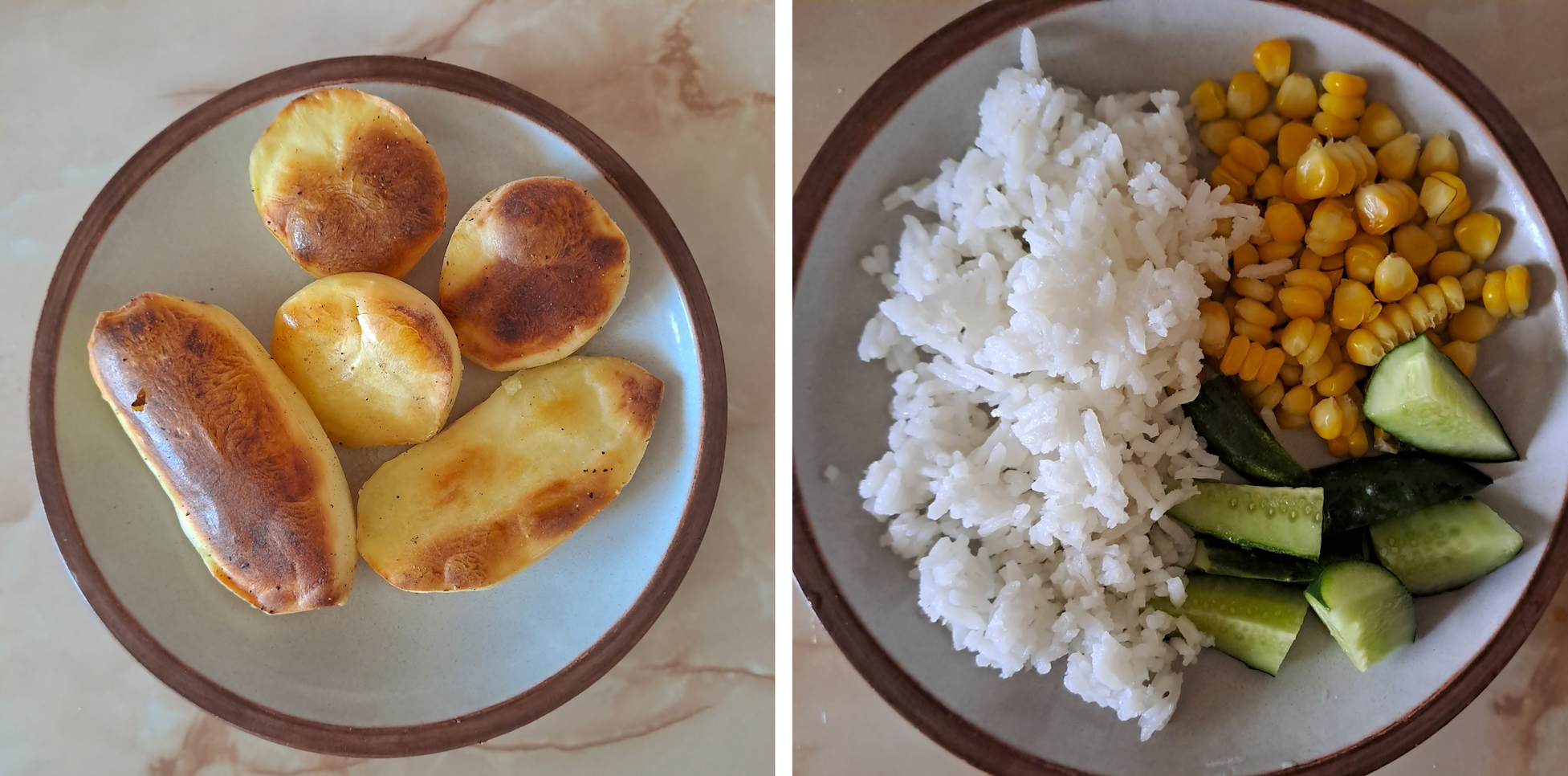

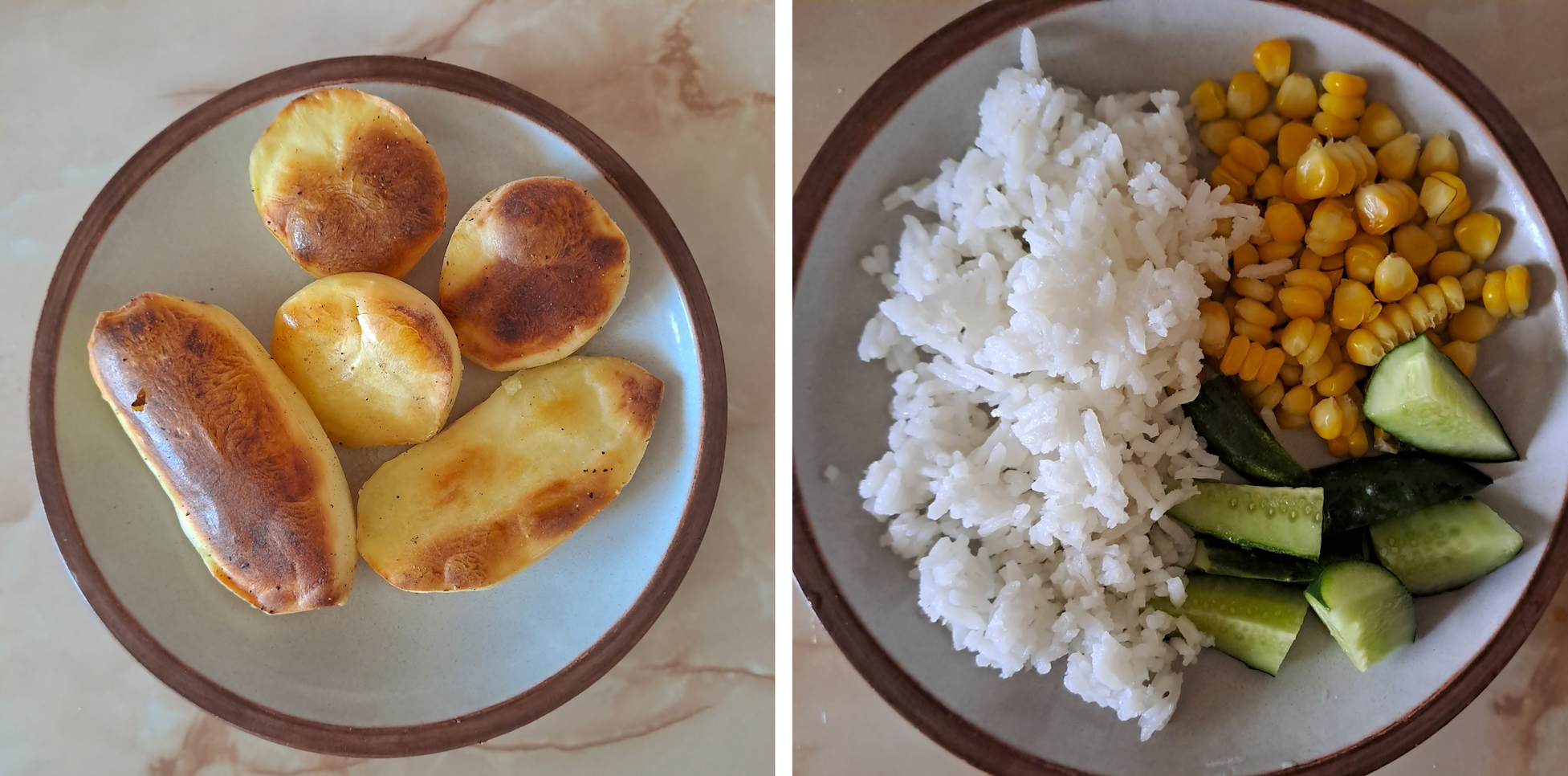

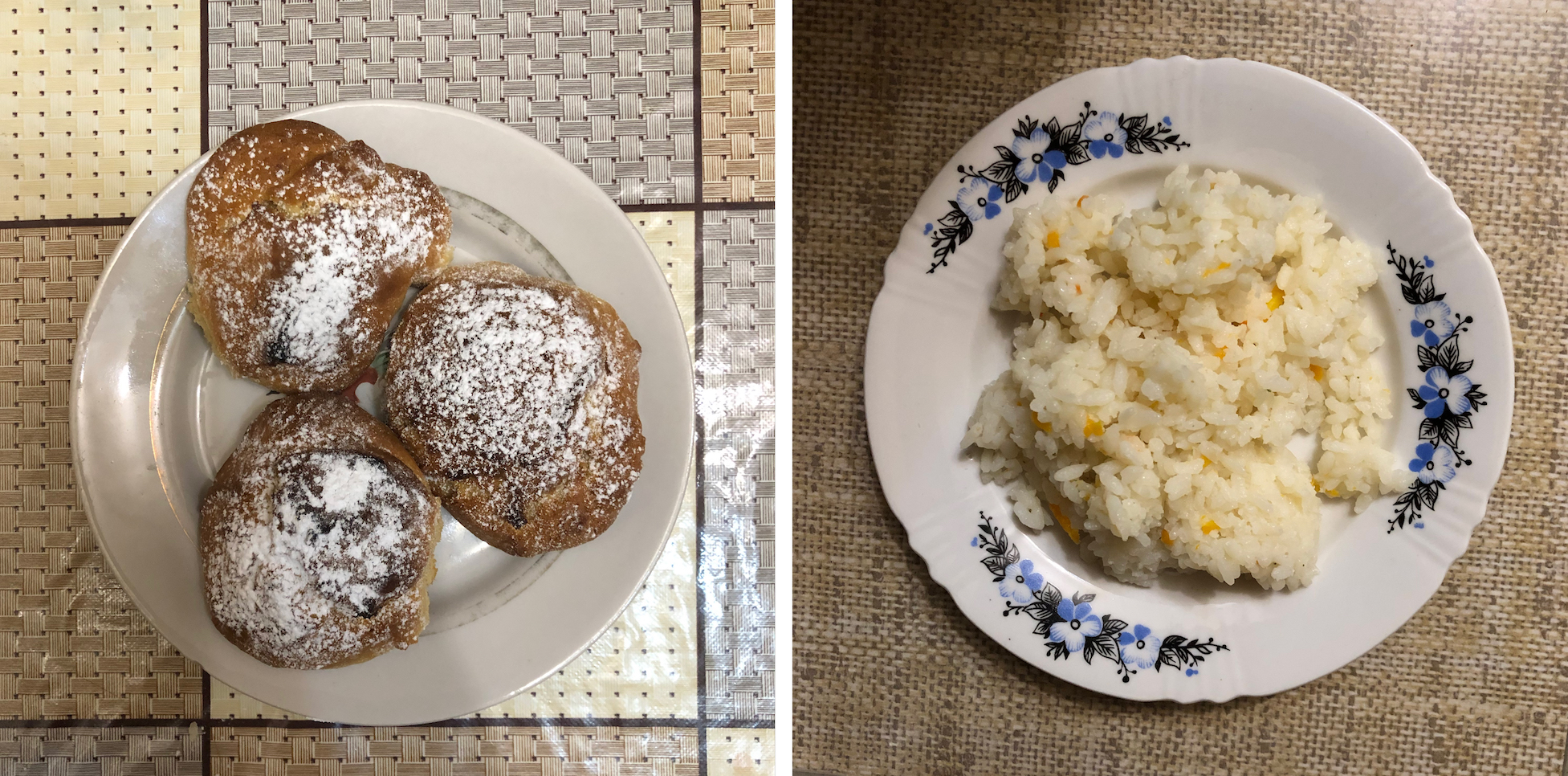

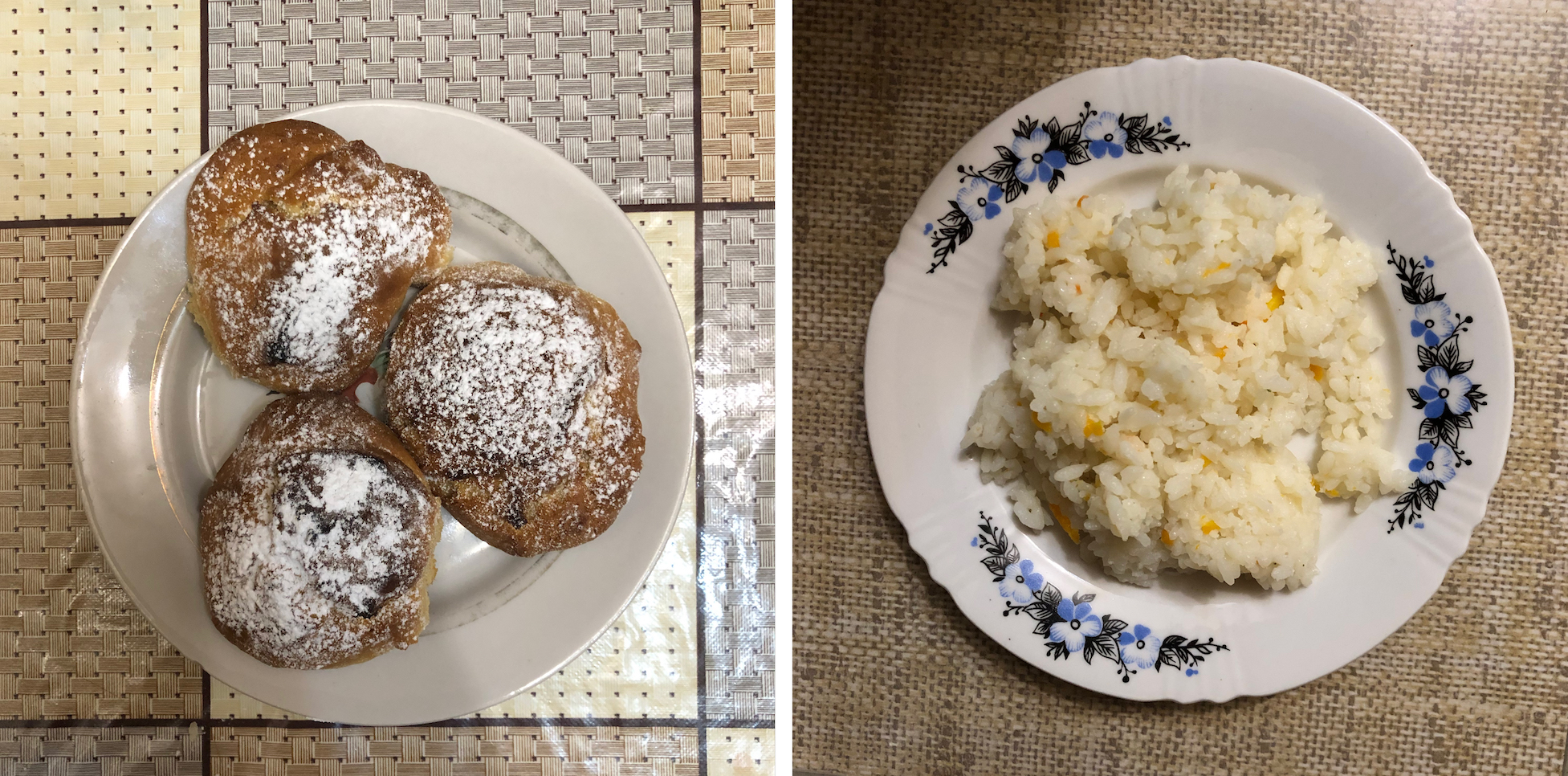

Raya’s meals

July 27

July 28 and 29

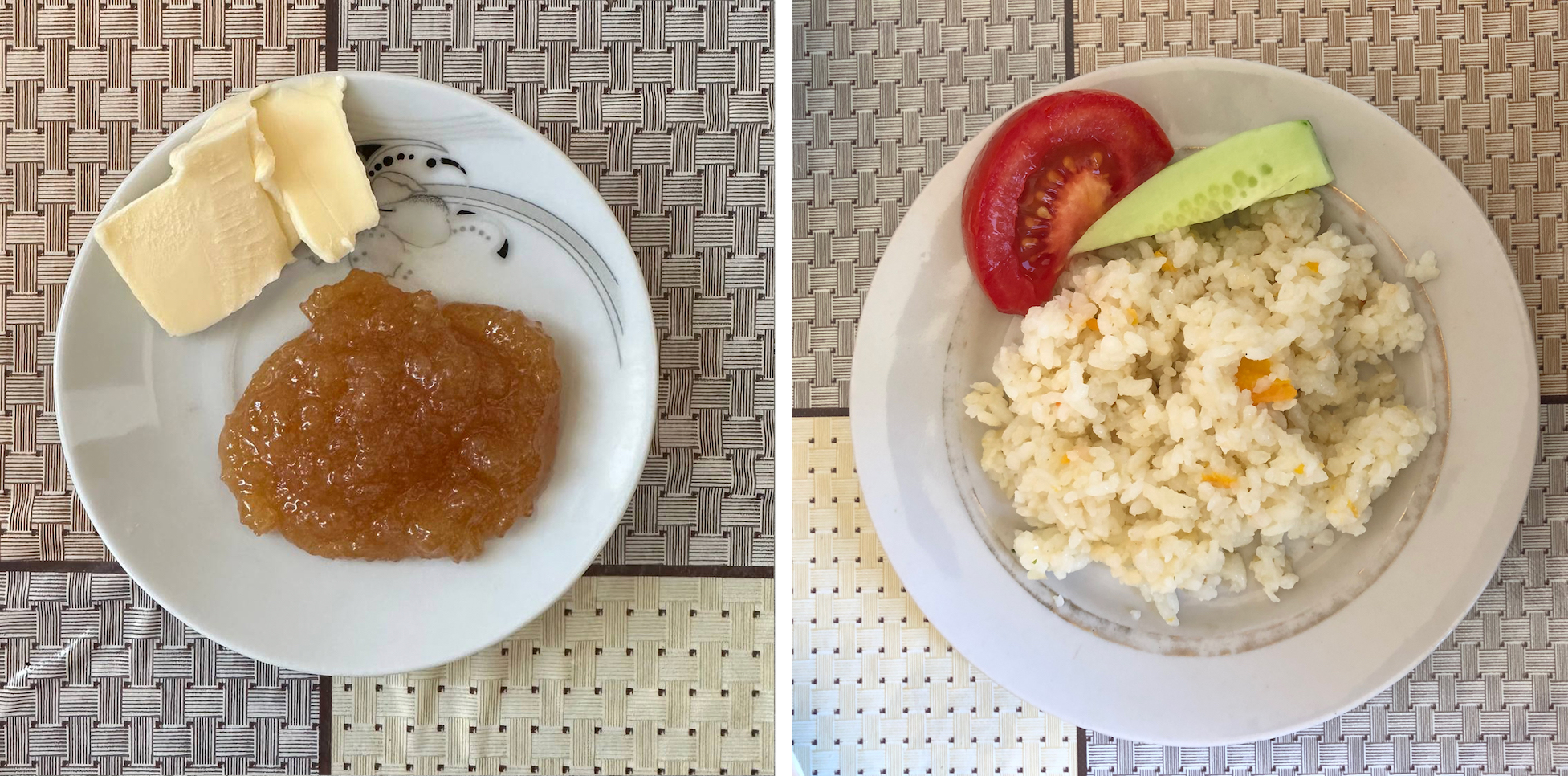

Anna’s meals

July 27

July 28

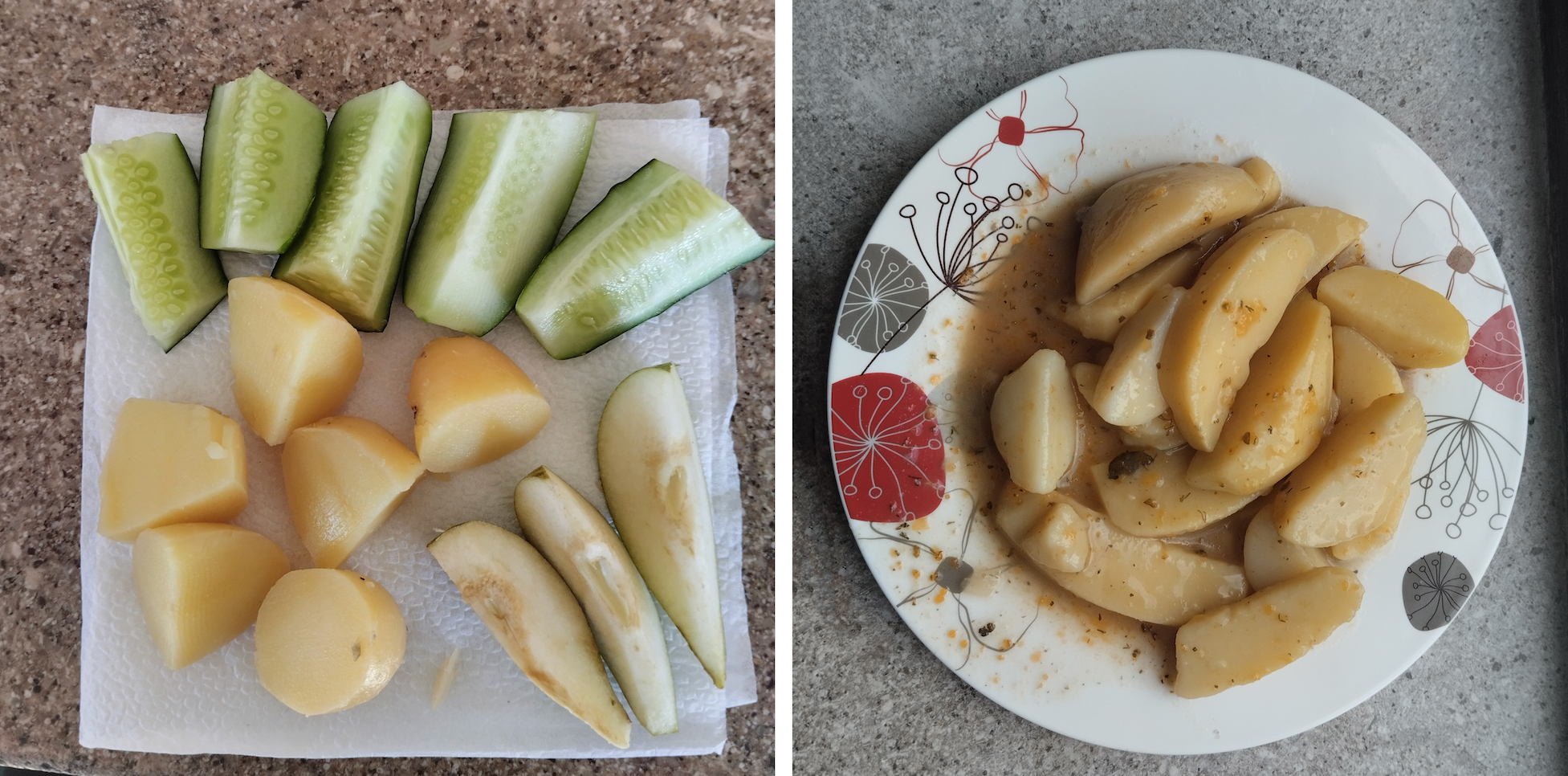

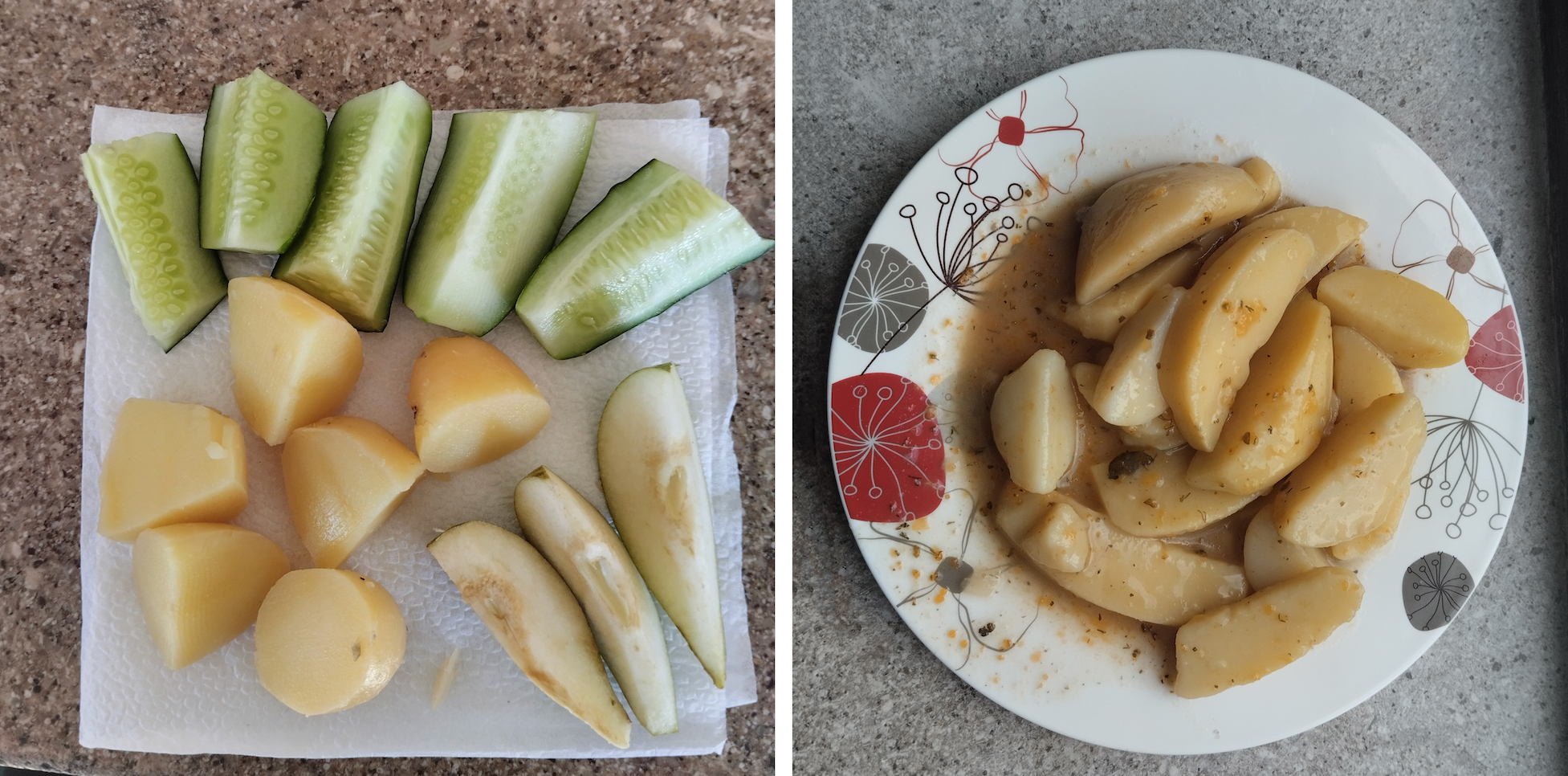

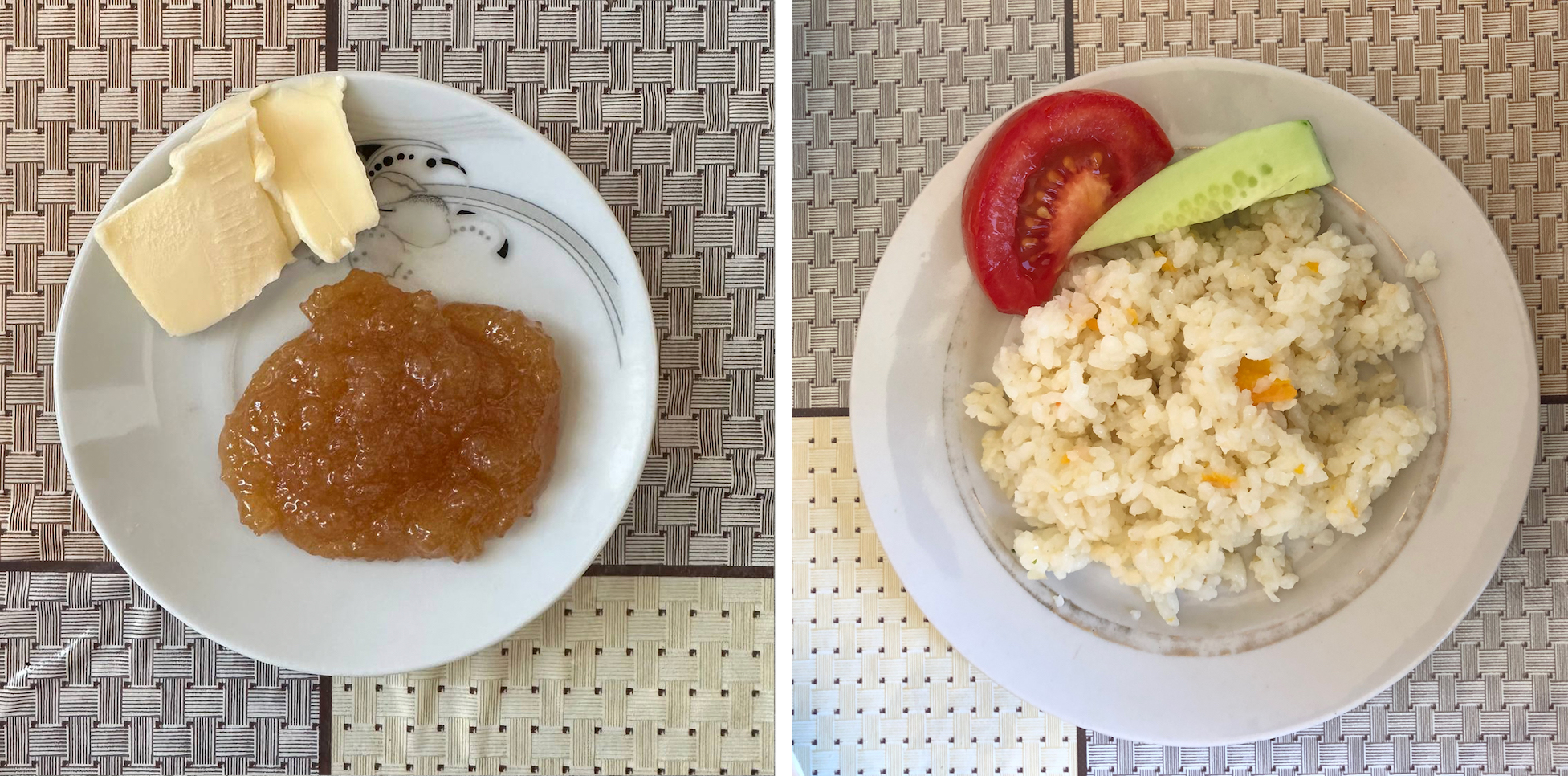

Vera’s meals

July 27

July 28

Larisa’s meals

July 27

July 28