“What should we talk about?”

“The blockade.”

“What is a blockade?”

“A blockade is when there is no food.”

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), forcibly displaced children from Artsakh are showing signs of severe psychological distress, and without immediate assistance, their psychological health is at risk of deteriorating further.

“This dialogue is most frequently repeated in my conversations with children from Arstakh,” says Hasmik Ghushchyan, a psychologist with the Ministry of Internal Affairs Rescue Services.

“It is not within my scope to directly inquire about what has occurred; we can only discuss it if the child brings it up,” says the psychologist. She notes that the children of Artsakh have witnessed, endured, and felt things that even adults would struggle to comprehend. After nine months of deprivation, 24 hours of bombardment, and in some cases, a second displacement, these children require attention and extremely cautious care.

“The displacement, along with military operations and blockade, has had a severe impact on their physical, psychological and mental well-being. These children will continue to suffer the consequences of these incredibly traumatic experiences for years without ongoing support.”

Understanding Timing

According to Albert Grigoryan, a member of the Psychological Service, children are more likely to trust female psychologists and to trust them more quickly. But, the situation changes when the team arrives in their “911” car. The children immediately start smiling upon seeing the vehicle.

“We provide psychological first aid to people who have been displaced from Artsakh. Our focus is on working with children. While adults often claim to be doing well and not in need of help, they can still rely on their relatives and friends for support. With children, it is more challenging. They are less likely to comprehend the situation and even if they do, they may struggle to express themselves and seek help.”

“When they say the child is having issues, our first question is, ‘starting when?’ Nothing happens in a void; everything has clear reasons. We previously worked at the largest refugee shelter in the city of Ararat, with the Artsakh children living at the local sports hall. Now, we are in Artashat, this time at a kindergarten that has been converted to accommodate the forcibly displaced.”

Psychological First Aid

Sona Muradyan of the Psychological Service says that each member of their team has a specific role: “One is in charge of gathering information, another assesses primary needs, another works with children, and someone else focuses on the elderly. Before working with children, we must first obtain permission from their parents. Then we assess the child’s emotional state, their experiences during displacement, and their journey to Armenia.”

“This is psychological first aid –– this is not in-depth individual therapy. However, if we identify a child in need of more specialized assistance, we inform the parents.”

Gohar Mkhitaryan from the team says that they always provide coloring books, paint, and books about fairy tales for the children: “Many of them have not even been able to bring their clothes, let alone their favorite toys. It is important for the children to have something to keep themselves occupied and not focus too much on conversations with the adults.”

“We Are Unwanted”

Karine Harutyunyan is the director of the Artashat kindergarten, which is hosting displaced individuals. She has been coordinating the resettlement of people from Artsakh. In Artashat, there are 17 families consisting of 73 people, with 34 of them being minors.

“Throughout the day, many people from different art schools visit, offering classes in macrame, tapestry, painting and other subjects. The children have busy schedules.”

Gohar Grigoryan, from the village of Khramort of Artsakh’s Askeran region, says her three underage children were psychologically devastated in Artsakh. However, she now sees positive changes in them on a daily basis.

“When we were there, one of my kids kept saying, ‘no one wants us’ but now that we are here, the children feel the attention, which serves as a welcome diversion for them. Sometimes, I wish I was their age.”

Zoya Yegoryan from Stepanakert despite leaving everything behind, she brought with her three cockatiels in a birdcage.

“I may have left everything behind, but could not leave my cockatiels. Seeing them now brings me joy, and the children love them too.”

They Draw What They Love

Hasmik Ghushchyan says she engages in fairy tale therapy with children: “We create fairy tales using characters and narratives suggested by the children. We try to develop the story in a way that ultimately portrays good triumphing over evil. The children really like it. Afterwards, we just draw whatever the children request.”

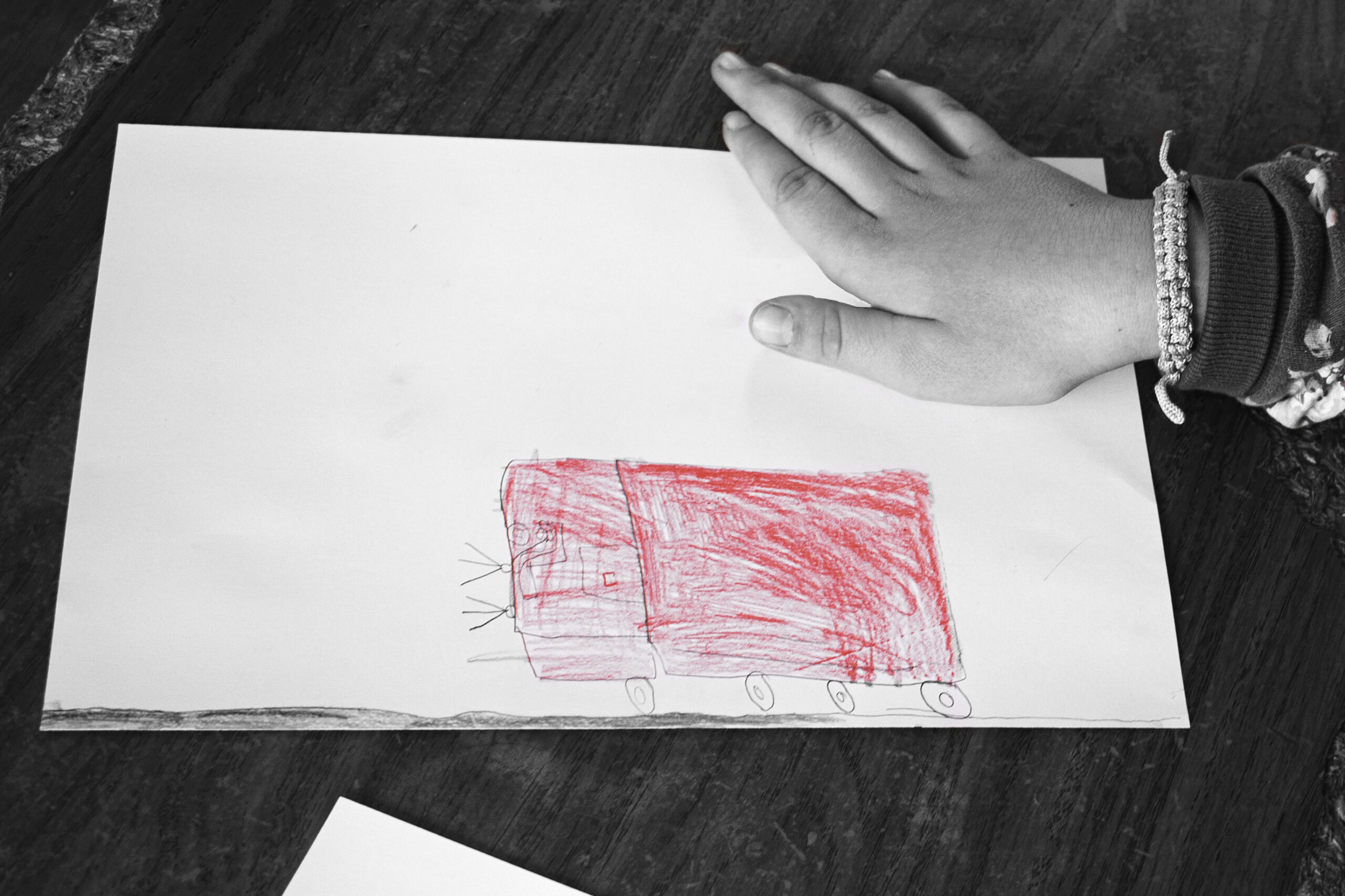

“Sometimes it is the drawings that indicate how much anxiety a child has at the moment. Children who feel safe draw the things they like, such as cartoon characters and their friends.”

“Our aim is for the children to experience a sense of relief from their anxieties after each visit. In our most recent session, one of the children finally drew something that a child feeling safe and relaxed would draw –– something they liked, rather than war, soldiers, or guns. The child drew our 911 vehicle.”