The families forcibly displaced from Artsakh will long remember the lack of bread during the months of blockade. That bread, often moist and bitter, has become a symbol of their struggles, deprivation, courage, and strength.

Zina Sahakyan, mother of six children

We Shared Flour

When we first arrived in Armenia, our relatives hosted us in their home. The table was set and there was bread on the table. Upon seeing it, my niece turned pale, and exclaimed, “Mom, is this bread?” We all broke into tears.

Occasionally, I managed to buy dough from the bakery. I would bring it home and invite my relatives to take half. Once, on a particularly tough day, my sister said, “We don’t need it, it’s barely enough for your family.” To which I replied, “If your children won’t eat this bread, mine won’t either.” It was a difficult time, but we knew we would survive this as well.

Two days ago, I baked bread that did not turn out well. When I showed it to my children, intending to throw it away, my son got upset. “Have you forgotten we did not even have this in Artsakh? Don’t throw it away, I will eat it,” he insisted.

Christine Shahgeldyan, baker

We Were Being Cursed

There was no wheat flour, we were baking bread from corn flour. Each person received 200 grams of bread daily, and that was with coupons.

People were lining up from one in the morning to get bread for breakfast. Only half of them managed to get bread. The situation was dire, with hunger on one side and high prices on the other. People made accusations, not caring whether it was appropriate or not. They claimed that we favored our relatives. However, this was never the case. We operated with coupons. We exchanged the coupons for flour. Despite this, people complained and cursed us. It was necessary to treat people delicately.

The work was strenuous for us. We worked all night, even during blackouts, and we were exhausted.

On the 16th and 17th of September, there was no flour at all. The situation was very bad. We received white flour on the last day. We sold it to people for 100 drams. That was the end; that was the last of our bread baking. People ate the white bread that day, and then the war began.

I remember my first thought in Armenia, when I realized that I could bake bread again without a flour shortage. The feeling when we reached Goris and saw bread… There is no need to describe how we felt.

Zarine Avagyan, baker

We Believed in Doing Good, Confident God Would Reward Us

They say that this is the fate of Armenians. Even baking bread is considered part of that fate.

We baked bread using three types of flour: white four, corn flour, and wheat bran. We were content because we didn’t go hungry that day.

There were families who would come to buy bread, and I knew some of them had many members. One such family had six children. They were allocated three loaves of bread, but I couldn’t bear it. During that time, bread was already being distributed using coupons. Our administration mandated that we should distribute bread according to these coupons to receive flour also by coupons.

There was an old man living alone who would come and take 200 grams of bread a day. I understood that this was not enough for him, so I gave him a loaf of bread. In such cases, we always thought, let’s do good, and God will reward us.

Speaking About Horrible Things in Another Language

On August 29, 2023, I highlighted the issue of the Artsakh blockade in Zurich, Switzerland. Using my body and a net filled with bread, I depicted the hunger and adversity faced by the people of Artsakh.

STOP THE BLOCKADE: OPEN THE ROAD was my inaugural performance in Zurich. Initially, I was hesitant to undertake projects in Switzerland, as I wanted to familiarize myself with the local context and environment. However, as media reports about Artsakh and the severe hunger there started to proliferate, I could no longer wait.

For three days, I collected bread as a volunteer at the FOODSHARING project, which focuses on preventing food waste. This means I used surplus bread to avoid wasting food. My friends and I then used this bread to create an installation with a net.

It was important for me to address the issue of war through images and media pieces, using art instead of sharing another photo. This is the role of the photographer: to communicate about horrible events using a different language — the language of images and symbols.

Misha Badasyan, artist

Photos from Misha’s personal archive

Why Is the Bread On the Ground?

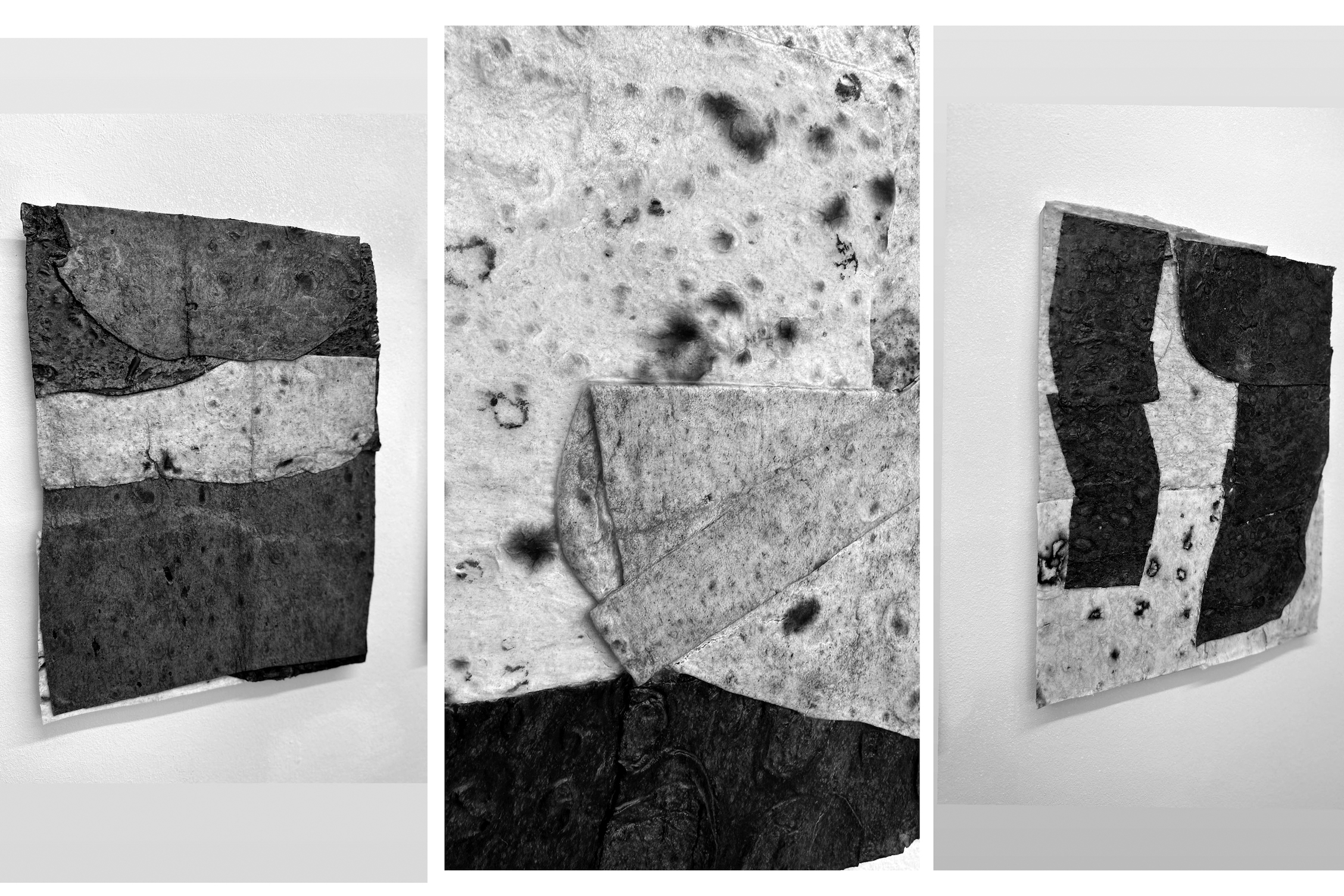

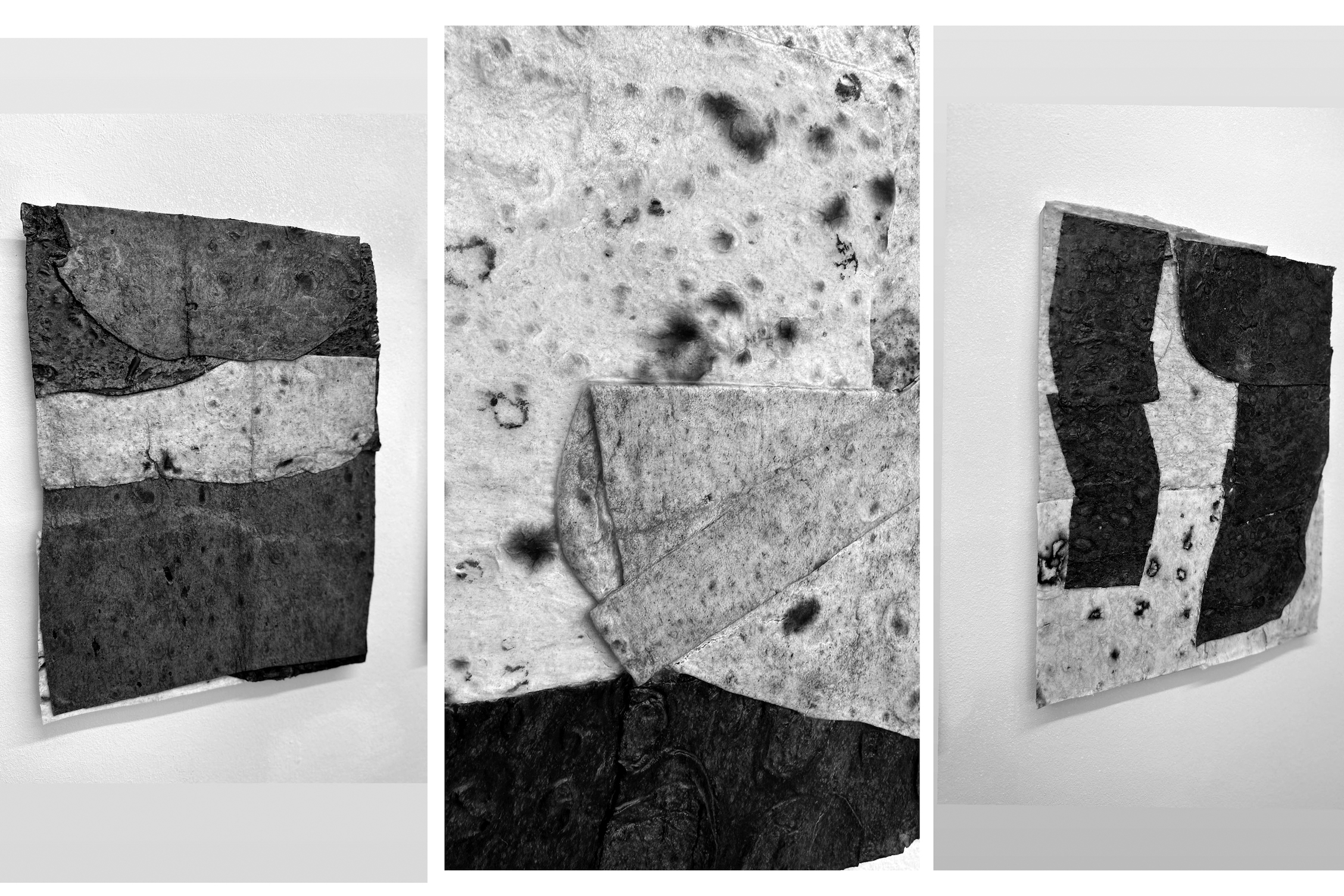

I create artworks using lavash. My latest pieces, made of this type of bread, were exhibited at an art center in Frankfurt.

Many viewers did not initially realize they were looking at bread. They asked, surprised, if it was leather or paper. Upon discovering it was bread, their interest heightened.

A year ago, I created an installation. I arranged lavash in the shape of Armenia’s map on the ground and noted that visitors could walk on it. For most people, this was not a problem and was even fun, except for one man from Syria. He was surprised to see bread on the ground. At that moment, I did not reveal that it was my work. Instead, I explained that it was an installation and its placement on the ground was meant to elicit reactions. He said, “No, in my country people are starving. This is unacceptable.”

I agreed and explained that was the point. Here, bread was casually strewn on the ground, seemingly without value. Yet, at this very moment, many people were starving and nobody seemed to be thinking about that.

Ani Barseghyan, artist

Photo from Ani’s personal archive