Может быть, выпадут лучшие дни.

Мы не увидим их… Поздно, усни…

Это — обман.

Maybe, there will come better days.

We won’t see them…It’s late, sleep…

It is all a lie.

– Andrei Bely[1]

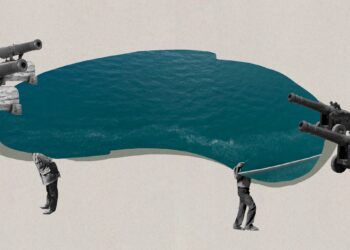

Throughout much of the 19th century, Russia viewed itself as a European power. However, due to its distinctive geography and socio-economic dynamics, it had to turn towards the east, acknowledging the vast territories beyond European Russia as an integral part of itself. In German this process can be simply described with the word Verostlichung (Easternization). Thus, this text embarks on a journey through 19th-century Russian history within the context of Verostlichung, ultimately culminating in the October Revolution of 1917. The following subheadings should be seen as a series of vignettes offering glimpses at the different aspects of Russian history in the 19th century. If some important historical events are omitted or not discussed in length it is with the purpose of not overburdening the reader.

Politics Between Reformists and Reactionaries

Catherine the Great’s reign ended during the French Revolutionary wars (1796). Her immediate successor, Paul I, failed to make a significant impact. His short reign was characterized by reactionary policies, as he rejected his mother’s reforms with the aim of concentrating power in his own hands. He also treated the noblemen as servants and removed their freedom from corporal punishment. Paul’s erratic behavior and his absolutist tendencies made him an unpopular figure among the nobles.

Although Paul I managed to establish a law of succession for the Romanov dynasty, a question that troubled his mother throughout her reign, he did not make any other lasting contributions to Russian history in the 19th century. Paul I was eventually assassinated on March 11, 1801, and his son, Alexander I, was proclaimed Tsar in his place.

Alexander I is often described as an autocratic idealist, torn between his desire for reform and his reluctance to curtail his own autocratic power. Despite his aspirations for change, he hesitated to take bold steps in that direction.[2] Nevertheless, the emergence of the reformist Mikhail Speransky seemed to signal that these expectations would be fulfilled.

Speransky worked tirelessly on a set of laws for the Russian Empire, with the goal of instituting local governance structures and creating a national assembly. His influence reached its zenith during Russia’s war with Napoleon, whose eventual defeat in 1812-13 elevated Russia to the position of a major European power. However, this external prestige did not reflect the internal state of affairs in Russia. Napoleon’s defeats in 1813 and 1815 resulted in an era of peace across the continent.

This meant that European rulers could finally attend to domestic affairs without worrying about external threats. However, it was at this point that Alexander I became involved with Christian mysticism, causing a conservative shift in his worldview. Additionally, the creation of the Holy Alliance, which partnered Russia with the conservative powers of the continent –– the Habsburg Empire and Prussia, further solidified Alexander’s alignment with the political status-quo established at the congress of Vienna in 1815. On the domestic front, this conservatism resulted in a decline in the influence of Alexander’s enlightened advisor, Speransky. Many of his reform plans remained unrealized and were archived. The same fate awaited the reform ideas of Nikolay Novosiltsev, who was asked by the Tsar himself to draft a constitution for the Empire in 1820. Although the draft reached the Tsar, it was never published or implemented. The reasons behind Alexander’s decision to shy away from implementing Novosiltsev’s reform agenda are still subject to debate. It is possible that the Tsar was influenced by conservative circles in St. Petersburg and especially in Moscow. The rebellion in faraway Spain could have renewed fears of a similar scenario in Russia if the autocrat showed any signs of weakness.[3]

In the end, Alexander’s reign delivered far less than it promised for internal improvements in the Empire. The political upheavals of the 1820s ensured that his younger brother, Nicholas I, would rule with unmitigated conservatism. The main characteristics of Nicholas’ reign were formed during and immediately after the Decembrist rebellion. Often described as an 18th-century coup in the 19th century, the rebellion lacked a coherent plan that would garner unequivocal support from all participants.

To begin with, the Decembrists were divided into the Northern and Southern Societies. The division was merely geographical. The Northern Decembrists sought mainly political change through the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, drawing inspiration from the Glorious Revolution of England (1688-89) and the American Revolution (1776). On the other hand, their southern counterparts embraced more radical ideas, influenced by the style and ideals of the French Revolution. They proposed centralizing the state and completely restructuring society, as outlined in the draft constitution of Pavel Pestel, the leading ideologue of the Southern branch. These notions were foreign to the Northern branch, which aimed to prevent the would-be regime from descending into despotism.[4]

The ideological breach between the two branches, among other factors, led to the eventual failure of the Decembrists in 1825. The uprising was suppressed, and the participants were either executed or exiled to Siberia. Nicholas I, as the new Tsar, could finally begin his rule. As expected, he had fears of future plots and rebellions. His policies aimed to suppress dissenting voices and force society into obedience. As a result, the Tsarist autocracy, which had been somewhat open to reformist ideals during Alexander I’s reign, transformed into a completely personalized and highly centralized rule.

During this period, the autocratic regime found its advocate in Sergey Uvarov, who drafted the three principles of Russian official nationalism in 1833: “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.” While devoid of the reformist tendencies of his brother Nicholas I’s reign, it could not be considered a complete stasis. Reforms were still planned and occasionally implemented, albeit with little success and on a limited scale. The discussions around reforms outweighed their actual realization, resulting in minimal progress. Historians of Russian history agree that the societal element played a minor role in the political life of the Empire during Nicholas I’s rule. Reforms were planned by small committees formed from the shrinking circle of Tsar’s trusted advisors. Russia struggled to break free from the legacy of Peter the Great time and again. The most significant achievement of Nicholas I was the establishment of a bureaucratic system. His reign saw the rise of subservient state servants known as “chinovniki”.

Nicholas I’s reign hampered the growth of society, alienated the intelligentsia through censorship, and ultimately saw the decline of Russian political prestige abroad. The once victorious nation, who had defeated Napoleon and acted as the gendarme of Europe, suffered a defeat on its own doorstep during the Crimean War (1853-1856). This war outlasted Nicholas I, who died in 1855. Alexander II inherited an empire facing military, political and economic crises. There were certain issues of utmost importance that could no longer be ignored or brushed aside. While his father’s oppressive rule had been balanced by Russia’s military strength on the international stage, the image of this powerful empire was shattered by the Crimean War. As a result, the empire could no longer justify its repressive policies. Alexander II’s most significant and audacious reform was the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. Following the implementation of the Edict of Emancipation, Alexander II turned his attention to other problems within the Empire. Reforms of local self-governments were carried out in rural communities and urban regions in 1864 and 1870, respectively, through the introduction of zemstvos (rural governing circles) and city dumas. The Russian judicial system was also reformed in 1864. The next priority was military reform, as the Russian army lagged behind its European counterparts. In 1874, universal conscription was introduced, allowing soldiers to be recruited from all social classes in the empire, rather than solely from the peasantry. However, none of the subsequent reforms held the same significance or impact of the emancipation of the serfs.

Alexander II’s reign was marked by his fervent pursuit of reforms. However, it also witnessed the rise of a politically conscious intelligentsia that was eager for change. To this group, Alexander II’s actions seemed timid and unsatisfactory. The repressive regime of Nicholas I failed to suppress the spirit of protest in the population; instead, it only caused it to solidify into a more extreme form. In the 1860s and 1870s, the Russian Empire witnessed the emergence of a radical group called the Narodniki, who aimed to represent the common people on the political stage.

The conservative turn in politics, following the demise of Alexander II and the ascension to the throne of his son, Alexander III, also marked a return to the ideology of Byzantinism, but with new, nationalist, specifically Panslavist contours. This ideology emphasized the belief in the Orthodoxy of Russia and its responsibility to protect it in the face of any challenge. Konstantin Pobedonostev, a trusted advisor of the young Tsar, held ultra-conservative political views that sharply contrasted with the more liberal tendencies of Loris-Melikov, an Armenian novus homo who rose to prominence in the last years of Alexander II’s reign but fell out of favor with Alexander III and eventually retired from politics.

In society, Russia regressed to the era of Nicholas I, albeit with one significant difference: the liberal reign of Alexander II had fostered a politically active intellectual movement that opposed the ultra-conservative societal politics of the young Tsar and Pobedonostev. However, the state recognized its internal weakness on economic and financial matters, and thus pursued grand projects like the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway during Alexander III’s reign. Russia turned its focus towards its eastern territories with the hope of rejuvenating the Empire economically and overcoming the regionalism of Siberia, which had become a safe haven for various centrifugal forces within the Empire.

Despite increased censorship and the rejection of the reform-minded bureaucratic circles, Alexander III had to accept that Russia could not be ruled solely by his own will, as the bureaucracy had become indispensable. Many of Russia’s internal conflicts stemmed from the fact that different ministries, such as transport, war and finance, often held opposing views on the modernization of the Empire. This lengthy and delicate decision-making process, despite the Tsar’s absolute right to make final decisions, ultimately led Alexander III to rely on the Ministry of Finance and his capable minister Sergei Witte to push for economic reforms while avoiding political ones.

However, even in a rapidly industrializing empire, Alexander III’s reign failed to alleviate discontent. In fact, it further angered revolutionary intellectuals. The true consequences of his conservative politics would be seen during the reign of his son Nicholas II. Nicholas II, who sought to continue his father’s political approach, had to rely on reform-oriented advisors to implement top-down modernization. Nicholas II placed too much confidence in the paternalistic image of the Tsar, which was no longer accepted among the Russian peasantry as it once was in the 19th century. Urbanization and industrialization had significantly altered the social fabric of Russian society, especially in St. Petersburg and Moscow. As a result, this meant that the Tsarist state no longer enjoyed active support or passive acceptance from the peasants, many of whom had already cut ties with the village commune and became urban proletarians. Adding to the challenge, Alexander III’s reign had also alienated many members of the educated classes, including students and intellectuals, who associated Tsarism with oppression and hoped for a revolution to finally end it.

A Tale of Two Cities

When discussing Russian history from the 18th century onwards, one can draw parallels to the novel, “A Tale of Two Cities”. St. Petersburg and Moscow, viewed as strongholds of different intellectual currents, represented two opposite ends of the same political and societal spectrum.

To paraphrase Andrzej Walick, Moscow was the old capital, the center of religious zeal and mysticism, and the stronghold of old noble families. It stood apart from the rationalized politics of the enlightened age, making it an antithesis to the imperial capital. On the other hand, St. Petersburg was a city without a past, more open to change and new ideas. It became a hub of rationalism, progressive thought, political pragmatism, and revolutionary plots, following a broader European pattern.

Moscow’s intellectual elites had to view ideas through the prism of “Ancient Russia”, a romanticized ideal invented in the late 18th century to contrast pre-Petrine Russia with the Europeanized Russia of the post-Petrine period.[5] Even the debate about the potential Trans-Siberian railway had to be discussed in the context of the St. Petersburg and Moscow divide.

Konstantin Pobedonostsev was well aware of the distinct cultural and political environments of the two cities. He tried, in vain, to persuade the young Tsar Alexander III to move the capital from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Pobedonostsev believed that in Moscow, the Tsar would be among traditionalists who were true allies of the crown, and any political unrest could be quickly quelled by the police forces.[6]

While it is important not to overstate the Moscow-Petersburg dialectics, there were significant differences between the two cities, partly due to the geographic distance separating them. This influenced the Bolsheviks’ decision to move the capital from Petersburg to Moscow. The move was not simply symbolic; it represented a rejection of a certain political and cultural outlook. St. Petersburg was designed as a gateway to the West, but by the end of the 19th century, Russia was becoming more insular.

Revolution and Intelligentsia

To fully understand the extent of transformation that the Russian Empire underwent in the 19th century, it is important to consider not only geography and politics, but also the diverse range of intellectual currents in the country. Unlike the lightning-fast and top-down Petrine reforms, the 19th century saw intellectuals voicing their demands and opinions on the future of Russia. The crown was no longer solely responsible for imposing change on a passive population. Particularly after the reign of Nicholas I, this segment sought to achieve its goals through practical, albeit radical, means.

In the 19th century, like in many other parts of Europe, nationalism had a significant impact on cultural life in Russia. Intellectuals grappled with various issues related to Russian society. During the 1830s and 1840s, two distinct currents of thought emerged in Russia known as Westernizers and Slavophiles. One group criticized Russia’s rural backwardness, while the other saw it as the country’s only hope for survival. It is important to note that both the Westernizers and Slavophiles were influenced by Western ideas. The main difference between the two groups was their relationship to Enlightenment rational thought. The Westernizers embraced this philosophy, while the Slavophiles looked back to the romantic ideals of the early 19th century and projected them onto the Russian past, adding their own unique elements. This led to idealized descriptions of ancient Russia, preserved only in the peasants’ way of life, and constant arguments against rational philosophy from Europe. The Slavophiles’ fascination with ancient Russia was part of a broader European fascination with the Middle Ages following the French Revolution, which had unleashed a sense of nostalgia.

While the Slavophiles indulged in unattainable and long-gone utopias, the Westernizers set out to challenge the existing social conditions of their country. Although their ideas also resembled a utopia, it was a future-oriented and action-driven one, which had the potential to disrupt the life of the Empire. Thinkers like Alexander Belinskiy sought to emancipate the individual from the shackles of autocratic rule. Even though this philosophy did not immediately lead to action, it laid the foundations for the action-oriented philosophy of the following decades.

The Crimean War marked a shift from intellectual indecisiveness and retrospective utopias to a philosophy focused on action. This shift was foreshadowed by the Westernizers, who believed that philosophy should acquire a practical purpose to move beyond pure reflection. The true inheritors of this philosophy were intellectuals who actively voiced their opinions through politically-motivated disruptive actions after Alexander II’s reforms.

While the Slavophiles were involved in the emancipation of the serfs for their own interests, the Westernizers saw Alexander II as an ally and believed in the creative agency of the state. Another group, consisting of radicals and revolutionaries, questioned the validity of the reforms during their implementation. This philosophy, known as “Russian socialism,” emerged through the writings of Alexander Herzen, who combined elements of Slavophile and Westernizing thought. Herzen advocated for preserving the Russian village commune, a pre-capitalist form of socialism, while also advocating for individual freedom and rejecting capitalism and proletarianization.

While Herzen remained primarily a theoretician, thinkers such as Nikolay Chernyshevsky tried to agitate the newly emancipated serfs into open uprisings. The Narodniki movement, with its return to the soil movement, opposed both the liberal intellectuals who still hoped for reforms through the state and the ultra-conservatives who rejected Western ideas and supported Tsarist autocracy and Orthodoxy. The Russian intelligentsia, as portrayed by Sergei Bulgakov in his essay “Heroism and Asceticism”,[7] saw its heroic role in educating the peasants and helping them overcome oppression.

Some of the Narodniki’s methods and ideas were later adopted by revolutionary socialists and communists in the Russian Empire, who used them to pursue the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Circle of Tchaikovsky, a populist offshoot, started disseminating revolutionary ideas among the growing proletariat in St. Petersburg in the early 1870s.[8] Amid the sweeping political ideologies in Russia, there were also solitary and eccentric figures like Afanasy Schapov and Konstantin Leontiev. Schapov, representing Siberian regionalism, studied the struggle between Russian centrifugal forces and the Muscovite state. He believed that the Russian peasants had their own way of life and did not need the mediation of the intellectuals.

Siberia became a refuge for politically persecuted intellectuals in the 19th century, starting with the exile of participants of the failed Decembrist coup in the 1820s. Leontiev, known as the Russian Nietzsche, advocated neo-Byzantinism, which envisioned Russia’s historical mission as conquering Constantinople and ushering in a new cultural phase. However, later in life, Leontiev regretfully admitted that Russia’s future might lie in socialism.[9]

Finally, with the death of Alexander II, the reform era came to an end. Alexander III’s court embraced a significantly chauvinistic version of Slavophile thought, known as Panslavism. Alexander III presented himself as an Orthodox father figure to the people, while championing Russian nationalism with the support of Konstantin Pobedonostsev. These reactionary politicians had to face a final showdown against the revolutionary socialists, leaving liberal-minded intellectuals caught between opposing forces. Their actions inevitably displeased one group or the other.

While conservatives and revolutionaries were present throughout Europe at the time, the problem was particularly pronounced in Russia due to internal backwardness and the declining legitimacy of the Tsarist regime.The regime struggled to fully control the general population. The awakening of the masses in the Empire proved fatal to the Tsarist state, as it failed to understand the desires of the people. Alexander III’s reactionary politics were no longer as effective as they were during the reign of Nicholas I. Reforms and lighter censorship over the previous two decades had cultivated a group of socially active people. Although this educated class lacked the support of the ordinary people, mainly villagers, who they claimed to represent, it was clear that the populist movement would not be stopped by exile or imprisonment. The radicalism that led to the central government cracking down on those involved in Alexander II’s death persisted. The populists continued to hope for a change in the regime by threatening the lives of the ruling circles and the members of the Tsarist family. Even a minor crisis could trigger movements that the Tsarist regime could not effectively counter.

In the end, grappling with Western philosophy influenced the development of Russian philosophical thought which was influenced by both native traditionalism and political radicalism. In both thought and politics, the Russian Empire began to look towards the East to understand itself and assess its potential.

However, when the Revolution came, this rich tapestry of various intellectual currents became one of its casualties. It gradually had to yield to the dominance of Bolshevism.

Economy and Material Life

Russia entered the 19th century in a precarious economic and financial situation. The strained fiscal system and the trading difficulties were the results of the Napoleonic wars. Throughout the century, the Russian state had to deal with increasing state expenditure and find new sources of revenue, especially during military conflicts along its frontiers in the Far East, the Armenian highlands and the West. Military expenditure consistently strained the financial abilities of the Russian state. Despite attempts by successive finance ministers to reduce the military budget, they faced strong opposition from the Ministry of War, which believed that military ventures were essential for the Empire’s success. It is important to acknowledge that the Empire’s biggest challenge was maintaining a European-standard army while relying on revenue from a population that was not as economically prosperous as that of rival European states.[10]

During the last decades of the 19th century, Russia began to industrialize at a rapid pace. However, its industrial capability was still far behind that of European states, which had already made significant progress in areas such as iron production, railway building and armament due to early industrialization.

While liberal economic policies were dominant in the 1860s, the Russian state started to intervene actively in the economy from the 1870s onwards. This intervention included promoting specific aspects of economic life, like railway construction, and providing support and funding for selected enterprises over others. The finance minister, Michael von Reutern, oversaw this shift away from private enterprise following the 1873 stock market crisis. However, his successor, Nikolai von Bunge, attempted to move away from interventionist and restrictive policies.

During Bunge’s tenure, efforts were made to improve working conditions in factories, and the employment of minors was prohibited by law in 1882. However, his position was weakened by two consecutive years of poor harvests in 1883 and 1885, which further worsened the Empire’s economic troubles.

The conservative forces in the government, led by Pobedonostsev, pushed for Bunge’s resignation, which occurred in 1887. Pobedonostsev, a firm believer in the infallibility of the autocratic regime, advocated for protectionism and constant state intervention. However, even future finance ministers did not fully align themselves with Pobedonostsev’s economic ideas.

In the 1890s, a new era in the economic life of the Russian Empire began with the death of Alexander III in 1894 and the appointment of Sergei Witte as Finance Minister in 1892. Witte aimed to develop Russia’s domestic industry, not only focusing on the major cities and European part of the Empire but also looking towards the East to access markets there.

The construction of the Trans-Siberian railway, a substantial achievement during Witte’s tenure as minister of finance, was an integral part of his economic and political plan. Witte spared no resources for this ambitious project, which continued until the early 1900s and cost over one billion rubles, when the Empire’s annual budget was less than 1.5 billion rubles.[11]

The debates and discussions that preceded the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway deserve their own treatment, as they demonstrate the shift in Russian political and economic thought during the 19th century. Initially, the government planned to create a number of railway routes to link Siberia and the Urals. However, these plans were not indicative of the grand project that slowly emerged. By the mid-1870s, debates arose about linking Siberia with European Russia, resulting in two rivaling routes. The ideological battle between two economic schools of thought played out along Moscow and St. Petersburg lines. One plan proposed building a railway along the southern route, linking Siberia to Moscow. The other, put forth by Minister of Transport Konstantin Posyet, aimed to link Siberia to St. Petersburg via a northern route. The southern route was considered more viable due to its passage through a densely populated territory with better trade and industry. The northern route, in contrast, would pass through sparsely populated and economically lacking lands. Supporters of limited government intervention favored the southern route, while technocrats like Posyet hoped to increase the Empire’s economic vitality by supporting underdeveloped areas along the northern route. Both options were ultimately shelved due to the o financial resources being consumed[12] by the onset of the Russo-Turkish war in 1878, preventing the execution of either plan.

In the 1880s, as the Russian economy slowly recovered, the issue of a Siberian railway gained importance once again. The two opposing viewpoints clashed once more, but this time the vision of Posyet, promoted by the Ministry of Transport, emerged as the winner. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Finance still hesitated to provide the necessary funds for the construction of the railway. The situation only changed when Sergei Witte came to power. Witte, who had been compared to the Spanish conquistadors due to his adventurous nature, pursued both economic and political goals. Economically, he aimed to connect Russia to the eastern market, while politically, he sought to colonize underpopulated territories by introducing Russian or European civilization to areas that were considered historically “untouched.” As Mark Bassin describes this process, which had already begun in the mid-19th century, “…through their progressive civilizing activities among the Siberian heathens, the Russians believed in effect that they could transform the quality of their own civilization.”[13] The Trans-Siberian railway was not only a result of this inward turn of Russia, but also an accelerator of it. From then on, Siberia played a more significant role in the life of the Empire than ever before.

The fact that the railway did not meet expectations should not diminish its importance in linking the Western and Eastern halves of the Empire. It also made Russia realize its reliance on the eastern territories, as some of Siberia’s economic potential was only discovered during the railway’s construction, after a thorough geological study of the area.[14] The first trial for the newly finished railway came in February 1904. Initially, the Russian war effort against Imperial Japan relied heavily on the Trans-Siberian railway.[15] However, facing consecutive military defeats, the Empire eventually experienced its first major revolution of the 20th century.

Revolutions and the Fall

After the Emancipation Act of 1861, the Russian Empire underwent a lengthy and tumultuous process of industrialization, reaching its peak in the late 19th century. This process coincided with the growth of the urban population, as emancipated peasants flocked to work in factories. The industrial proletariat began to slowly emerge, whether through the workers’ own initiative or with the support of the radical intellectuals, students, and academics who educated the workers and prepared them for their role in revolution and change.

With the Russian Empire’s astonishing increase in the number of workers, reaching 2 million according to the 1897 census, particularly in cities like St. Petersburg and Moscow, it came as no surprise that both the state and various political groups, including liberals, populists and socialists, placed their hopes or fears in the growing proletariat and its potential for disruption.[16] Initially, the urban worker still maintained ties to their village commune and had to navigate two distinct identities: one as a peasant who saw the Tsar as a paternal figure and benefactor of the common people (Alexander II was known as the Tsar Liberator), and the other as a worker who faced not only the whims of their employer but also the scrutiny of the Russian state, which viewed strikes or protests by workers with suspicion.

However strikes gradually became part of the working-class culture in Russia beginning in the 1870s. The government feared a similar situation to the one in Western Europe, where protests had a crippling effect on the Empire’s political and economic state. Considering the long-term development of the working-class movement in the Russian Empire, it seems logical that the workers were the main driving force behind the revolution that gripped the Empire in 1905. Nevertheless, even with this in mind, the revolution was the result of the exacerbation of what began as a peaceful protest and ended with a march to present a petition to the Tsar at the Winter Palace.

After the appearance of the protestors, the imperial guard opened fire on them in an event known as Bloody Sunday, which marked the start of the active phase of the revolution. Workers’ strikes soon spread in the industrial regions of the Russian Empire, and in some regions like the Caucasus, it took on an ethnic character. For example, in Baku, Armenians and Caucasian Tatar groups clashed. Both the periphery and the center of the empire were paralyzed, and the war with Japan ended in defeat. The autocrat, Nicholas II, was forced to introduce the State Duma and grant a constitution, theoretically diminishing the power of the Tsar. Concurrently, there was an increase in the process of Russification, which may have been another symptom of the declining political importance of the Empire. In an attempt to reassert Russian influence in the various parts of the multiethnic Empire, Nicholas II antagonized the Finns, who had previously enjoyed a state of relative autonomy, and the Armenians, who were among the most loyal subjects of the Empire.[17]

Nicholas II’s reign is also notable for the presence of Pyotr Stolypin, the last great Russian reformer, whose legacy is still celebrated in Russia. In 1906, he became both the prime minister and the Minister of the Interior of the Empire. His agrarian reforms aimed to privatize land ownership in rural Russia in order to increase agricultural capacity and create a more conservative landowning class that would be less likely to incite revolution. Stolypin sought stability through reform,[18 but he faced challenges from the Tsar himself, who feared that his popularity might affect his image among Russians. Despite opposition from Nicholas II, Stolypin persevered, though some of his plans were occasionally thwarted by the paranoid Tsar.[19] With the demise of Stolypin, no reformer of his stature appeared in Russian politics. As a result, the Russian Empire entered the First World War ill-prepared compared to other belligerents. Ultimately, Nicholas II’s erratic decision-making plunged the Empire into an even greater crisis, from which neither the Tsar nor the Romanov dynasty could recover. The period during and after the Great War has raised questions about Russia’s 19th-century history, including whether the Empire’s belated political and economic reforms were to blame for its downfall. While it is easy to retrospectively identify the root cause of major upheavals, it is important not to hastily pass judgment on the quality or timeliness of the numerous reforms enacted in the Russian Empire after 1861.

In hindsight, one can argue that the reforms came too late. The failure to establish a parliament, due to the reluctance of Alexander I and the neglect of his successors, came at a high cost. The reforms implemented by Alexander II were groundbreaking and unquestionable. However, the results of these reforms took longer to materialize than anticipated, and their impact on the Tsarist state, whether positive or negative, could not have been foreseen from their beginning.

The revolution of 1905 was initially suppressed with the help of the army and mitigated through the introduction of the State Duma and the constitution of 1906. However, the outbreak of the Great War provided another opportunity for revolutionaries to overthrow the Tsarist regime. The liberal revolution was eventually followed by the communist revolution. Ultimately, the defeat of the pragmatic and liberal elite revealed a desire for an even more radical change that would completely reshape the Empire. Autocracy, however, persisted and eventually gave way to totalitarian rule.

A desperate Nikolay Berdyaev questioned whether a revolution had truly occurred in Russia. According to him, the methods of governance did not significantly change, despite the shift in rulers.[20 Nonetheless, an important political change did occur in Russia, which further solidified throughout the 20th century: Russia’s isolation from Europe.

In the 19th century, Russia still considered itself as part of the Concert of Europe. The Tsars, although desiring autocratic rule, did not aspire to be Oriental despots but rather European monarchs. Despite their intentions, history took its own course, and Russian history in the 19th century became one of unfulfilled hopes and an eventual Verostlichung of the Empire and its Russian core.

Footnotes:

[1] An excerpt from the poem Великан (The Giant) written in 1901.

[2] Hildermeier, Manfred: Geschichte Russlands: Vom Mittelalter bis zur Oktoberrevolution, 2013 Munich, p. 706.

[3] Ibid., p. 742.

[4] Hildermeier, Manfred: Geschichte Russlands: Vom Mittelalter bis zur Oktoberrevolution, 2013 Munich, pp. 755-763.

[5] Walicki, Andrzej: The Slavophile Controversy: History of a Conservative Utopia in Nineteenth-Century Russian Thought, Notre Dame 1989, p. 70.

[6] Byrnes, Robert Francis: Pobedonostsev: His life and thought, 1968.

[7] Булгаков, Сергей : Героизм и подвижничество, in: Гершензон, Михаил Осипович (ed.) : Вехи. Сборник статей о русской интеллигенции, Moscow 1909.

[8] Venturi, Franco: Il populismo russo, Vol. III, Turin 1972, pp. 70-156.

[9] Walicki, Andrzej: The Slavophile Controversy: History of a Conservative Utopia in Nineteenth-Century Russian Thought, Notre Dame 1989, 522-523.

[10] Waldron, Peter: State finances, in: The Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. II: Imperial Russia 1689-1917, Cambridge 2006, p. 486.

[11] Ibid., p. 472.

[12] For a more detailed account of the debates and discussions leading up to the construction of the railway see: Marks, G. Steven: Road to Power: The Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Colonization of Asian Russia 1850-1917, Ithaca 1991, pp. 57-94.

[13] Bassin, Mark: Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840–1865, Cambridge 2004, p. 200.

[14] Marks, G. Steven: Road to Power: The Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Colonization of Asian Russia 1850-1917, p. 79.

[15] Fuller, William C., Jr.: The Imperial Army, in: The Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. II: Imperial Russia 1689-1917, p. 542.

[16] Zelnik, Reginald E.: Russian Workers and Revolution, in: The Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. II: Imperial Russia 1689-1917, pp. 617-637.

[17] Williams, Beryl: Late Tsarist Russia, 1881-1913, pp. 29-30.

[18] Ascher, Abraham: P. A. Stolypin The Search for Stability in Late Imperial Russia, Stanford 2001, pp. 208-261.

[19] Shakibi, P. Zhand: Central Government, in: The Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. II: Imperial Russia 1689-1917, pp. 446-447.

[20] Бердяев, Николай: Была ли в России революция, in: Народоправство, N. 15, 1917, pp. 4-7.

Also see

Tsardom and Empire: The Formation of Russian Imperial Ideology

Can Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its weaponization of the Orthodox faith and Putin's references to Peter the Great and his campaigns indicate historical precedents for Russia's re-emerging imperialism?

Read moreThe 1853-1856 Crimean War and Deep Contradictions in the International Order

The Crimean War in the 1850s did not resolve the geopolitical rivalries of the parties involved. The fight for influence in the Black Sea region continues even today.

Read moreRusso-Turkish Wars Through History

This new series presents the Russo-Turkish wars of the 19th-20th centuries, which were of crucial importance for the two segments—eastern and western—of the Armenian people.

Read moreThe Endless Geopolitical Struggle

Western attempts to infiltrate into the sphere of Russian influence have meant to weaken Russia and maintain constant tension. Could this result in larger clashes with more unpredictable consequences, this time between large geopolitical players?

Read moreThe Calamitous 1921 Treaty of Kars

The Treaty of Kars was signed under difficult geopolitical conditions. Turkey was able to use the “threat” of normalizing its relations with the West to extract maximum concessions from the Russian side, mainly at the expense of Armenia.

Read moreThe Calamitous 1921 Treaty of Moscow

The Treaty of Moscow reaffirmed, almost identically, the borders laid out in the Treaty of Alexandropol. Armenia, thus, conceded 20,000 square kilometers to Turkey. Mikayel Yalanuzyan reveals the details of those turbulent times.

Read moreBlack Garden Aflame: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict in the Soviet and Russian Press

A collection of articles about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict through the lens of Moscow by Dr. Artyom Tonoyan entitled, “Black Garden Aflame” will become a classic and a major go-to resource for scholars, writes Dr. Pietro Shakarian.

Read more200 Years of Armenia As a Refuge for Russian Emigres

While the recent wave of Russians moving to Armenia following the invasion of Ukraine has been surprising to some, it’s worth pointing out that Yerevan has hosted successions of Russian emigre communities for quite a long time now.

Read moreA Country That Changed Hands: A Conversation About Us and Us

Lusine Hovhannisyan was a witness and participant in the Karabakh Movement. Thirty years later, she had the chance to meet with someone who was on the opposite side of the barricades - a Soviet official who had tried to infiltrate the ranks of the demonstrators.

Read moreSeven Who Made History

limited podcast series

Seven Who Made History: Aleksandr Myasnikyan

The first episode in the series focuses on Soviet Armenian statesman Aleksandr Myasnikyan. An Armenian from Nor Nakhijevan (Rostov-on-Don), Myasnikyan was sent to Armenia by Lenin in 1921. His mission was to implement a more moderate approach toward governance, in line with Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP). Myasnikyan inaugurated the NEP era in Armenia, allowing the republic to rebuild and stabilize after the 1915 Genocide and the experience of the First Republic. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan.

Read moreSeven Who Made History: Shushanik Kurghinyan

A native of Aleksandropol (Gyumri), Shushanik Kurghinyan was a prominent Armenian writer, feminist, and social activist. Inspired by the 1905 Russian Revolution, she became a tireless advocate of the working people and advocated for their cause in her poetry. She was also a staunch advocate for women's rights, and she cared for Armenian refugees fleeing the 1915 Genocide in Rostov-on-Don. She later returned to Armenia, at the urging of her old friend Aleksandr Myasnikyan, during the NEP period. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan.

Read moreSeven Who Made History: Nersik Stepanyan

Born in Elizavetpol (today Ganja, Azerbaijan), Nersik Stepanyan was an Armenian Bolshevik activist and Party theoretician. A participant in the Russian Revolution in the Caucasus, Stepanyan later became known for his sensitive approach toward national cultures and traditions. A fearless public intellectual, he was also the most vocal critic of Soviet Georgian leader Lavrentiy Beria within the Soviet Armenian political elite. Tragically, Stepanyan’s arrest by Beria’s men in the summer of 1936 set the stage for the Stalinist Purges in the republic. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan.

Read moreSeven Who Made History: Aghasi Khanjyan

A native of Van in Ottoman Armenia, Aghasi Khanjyan arrived in the Armenian republic as a refugee. Attending Gevorgyan Seminary at Etchmiadzin, he was quickly drawn to revolutionary activity and soon became a member of the Bolshevik Party. By the early 1930s, Khanjyan had ascended to the post of Armenia’s First Secretary and became a popular leader known for encouraging a flexible policy toward Armenian national expression. His death at the hands of Georgian leader Lavrentii Beria in 1936 became a pivotal moment for Soviet Armenia during the years of the Stalinist repressions. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan.

Read moreSeven Who Made History: Stepan Shahumyan

This episode explores the “Lenin of the Caucasus” – Stepan Shahumyan. Originally from the Georgian capital Tbilisi, Shahumyan would forge his revolutionary legacy in Baku, as the leader of the Baku Commune during the Russian Revolution and Civil War. However, the story of Shahumyan is not only the story of the Baku Commune. He also played an instrumental role in developing the Bolshevik (and later Soviet) policy on nationalities. Executed by the British-aligned Socialist Revolutionaries in the Turkmen desert, Shahumyan continues to live on in the monuments and memories of Armenia today. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan.

Read moreSeven Who Made History: Anastas Mikoyan

A disciple of Shahumyan, Anastas Mikoyan was a native of the village of Sanahin, in the historical Lori region of Armenia. A survivor from Il’ich Lenin to Il’ich Brezhnev, he became renowned both in the Soviet Union and internationally for his role as a consummate diplomat and for his management of foreign trade. However, less well known has been Mikoyan’s role in Armenian affairs. Although forced by Stalin to participate in the 1930s repressions in Armenia, he would later become the major force behind de-Stalinization in his native republic. He also worked behind the scenes as an informal lobbyist for Yerevan in Moscow, securing key support for Armenia from the Kremlin. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan.

Read moreSeven Who Made History: Yakov Zarobyan

Born in Artvin (today northeastern Turkey), Yakov Zarobyan and his family fled as refugees to Rostov-on-Don. Later, the young Zarobyan began his career as a worker in NEP-era Ukraine. Eventually becoming a Party activist, he became engaged in the affairs of Soviet Armenia and rose to the position of the republic’s First Secretary in 1960. It was from that position that Zarobyan forged greater ties between Soviet Armenia and the Diaspora, and advocated for the commemoration of the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Although his tenure in Armenia was short, it would truly have a lasting impact on the republic. The series is hosted by historian Pietro A. Shakarian and produced by Sona Nersesyan. Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Read more