Listen to the article.

Just like a phantom limb can ache after amputation, memories of the genocide still live within Armenians today. It is this analogy between body and memory that historian Dr. Elyse Semerdjian explores in her book, Remnants: Embodied Archives of the Armenian Genocide. She disrupts existing narratives by incorporating nuance and an intersectional research approach. Her subject: abducted and tattooed women, and Armenian memory culture as a whole. She seeks to heal the “severed” memories with her feminist retelling of the genocide – perhaps the first of its kind.

“We’ve had a lot of political histories of the Armenian genocide. I wanted to offer something different. I benefited from those other studies, but I had different questions because my whole career has been spent trying to find the voices of women,” she explained in an interview with EVN Report. “By blending together these different disciplines as I have — feminist theories, sometimes critical theory and history, I’m trying to write a better history or a different history.” For Semerdjian, a historian of the Ottoman Empire and professor at Clark University with a history PhD from Georgetown University, Remnants is not her first endeavor. She has dedicated much of her work to women’s issues and Middle Eastern studies, and she is also the author of Off the Straight Path: Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo.

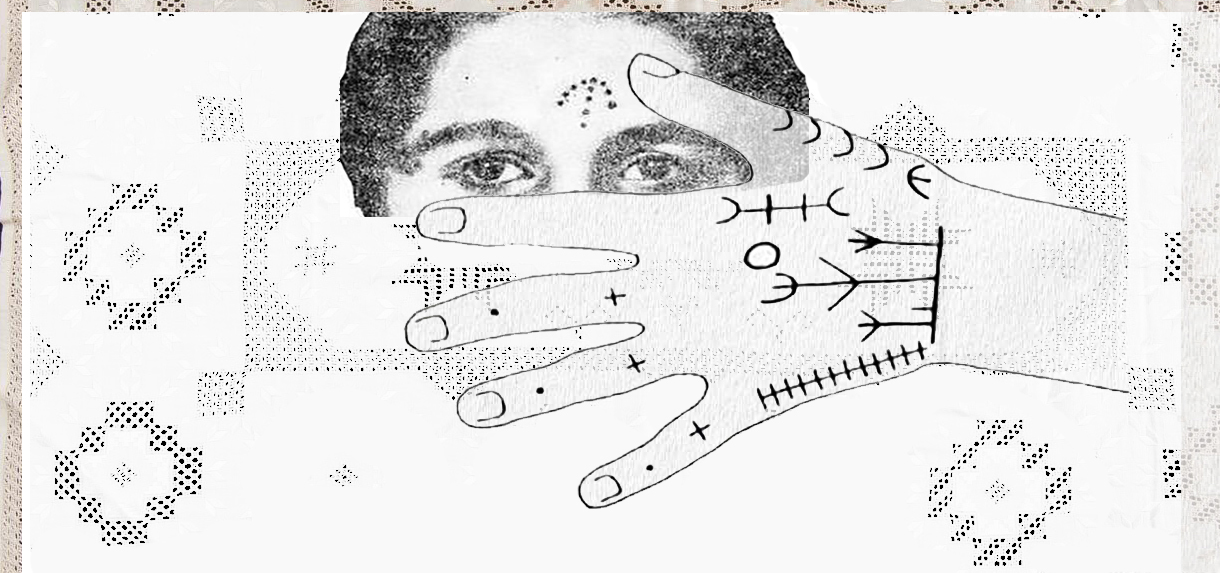

At its core, Remnants, published in 2023 by Stanford University Press, reexamines the experiences of Armenian women during the genocide. Many of these women were tattooed while living in Muslim households. This often accompanied abduction, slavery, humiliation, prostitution, and forced marriage, an attempt to dismantle Armenian society and family structures.

However, Semerdjian is fascinated by the ambiguity of these tattoos and their perceptions among Armenians. Typically, these perceptions were rooted in shame and impurity. But could they not also symbolize survival and resilience?

“Why was it that some women were overcome with shame to the degree that they had tattoo removal surgery, and why do some women within those communities have the same exact symbols but feel differently about them?” Semerdjian asks, hoping that she has “offered some new ways of thinking about it.”

Her research led her to understand the methodical, archival function of tattoos — from their ancient, indigenous and ritualistic origins, to their racial connotations in the West that emerged during the colonial era and into the 19th century. This evolution turned the tattoo’s image into one of otherness and deviance among many Christians. “In either case, the tattoos were viewed as a hindrance to Armenian national development because it could, in some instances, threaten the marriage-ability of those who bore them,” she writes in chapter nine. However, she also highlights that “While tattooed bodies were sensationalized in the age of mass media, the historical record also contains traces of those who resisted the dominant or commonsense view of tribal tattoos. In these counter narratives, the tattoos that Armenian survivors bore are understood to be marks of heroism, survival, resistance.”

Many Armenian genocide relief efforts were led by Christian missionaries, who often received tattooed women with dismay. “Mabel Elliott and other doctors who were working in Constantinople believed that the marks that these Armenian women had were marks that they had been held as sex slaves, which of course so many were,” she said. “They were also bringing with them an understanding of tattoos that came from another place where it was also a marking of a kind of colonial contact or possible racial mixing, racial miscegenation that they feared.” It is perhaps through this cultural divide in how tattoos were viewed that led so many Armenian women to go to extreme lengths to remove their tattoos, either out of fear of being seen as unmarriageable or simply out of intolerable shame. Some even committed suicide.

Blending archival research, anthropology, oral history, and her own Armenian heritage and fragmented ancestry, Semerdjian guides us through a historical timeline that is also an anthropological, ethnographic, and at times emotional journey. Semerdjian conducted interdisciplinary research in regions where some of the worst crimes of the Armenian genocide occurred. She sought hidden pieces of feminist history, interviewed people, and found a sense of closure to unresolved questions about female voices and her own cultural heritage.

Divided into three parts: Body, Skin and Bones, Semerdjian boldly uses the body as a metaphor for the broader Armenian experience. She introduces the term “prosthetic memory” to draw these parallels, defining memory as an embodied practice. “Rather than use the term postmemory, I’ve chosen to use the term prosthetic memory to describe the intergenerational and mediated transference of shared memories and stories because the term captures how memory is an embodied practice. Memory is stored within the body and genocide is remembered as body horror in which victims are forced to witness extreme violations of the body and desecration of the corpse,” she explains in the book’s introduction.

The book is structured around nine “remnants”: excerpts, letters, poems, and other documents. Each offers a form of written coping mechanism. “Remnants are also immaterial traces of psychic intergenerational trauma as descendants grapple with fragmentary postmemory: secondary traumatic memories that are not rooted in personal experience but have instead been transmitted through image, narrative, and storytelling to form a range of communal memories,” she writes.

In the early chapters, Semerdjian’s descriptions of the Ottoman Empire’s genocidal weapon of sexual violence against Armenian women and girls are often hard to read. There might be a temptation to look away, but the book urges the reader to do the opposite. For non-Armenian readers, the reading experience is grueling initially but ultimately eloquent and enlightening, perhaps different from the experience of Armenian readers.

A feminist retelling and exposé of the genocide’s patriarchal nature is essential. It offers a window to better understand contemporary Armenian identity and gender politics. Although Semerdjian does not explicitly connect past and present, Remnants opens a discourse on how these genocidal practices impact Armenian women today. “And there’s multiple reasons, but one among them could be that kind of epigenetic trauma, and also the way that the patriarchal conditions of genocide also have this weird ripple effect in terms of intensifying patriarchy in the survivor community,” she explained during the interview.

Using photo documentation and her “remnants”, Semerdjian uncovers hard truths. Her sources include the Prime Minister’s Ottoman Archives in Istanbul, despite the controversy around its activities regarding genocide denial, something she grappled with at times. She also used the Armenian Genocide Memorial Institute in Yerevan, the Karen Jeppe Archives in Denmark, the Zoryan Institute in Toronto, and the Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive at the University of Southern California. Additionally, she incorporated accounts from 25 respondents and an array of other archives and published material.

Her research journey was not straightforward; it was filled with puzzles and discrepancies. “The most contradictory thing in the whole story is how Armenians have a particular understanding of the tribal tattoos that women bore as a result of their time among Muslims in Muslim homes, particularly Arab and Kurdish homes,” she said. “And that over time, they become narrated as Islamic markings, as if the symbols themselves are religious. And what I found by looking at tattoo anthropology was that the practice is much more ancient and that the tattoos themselves can signify any number of things. And so that creates ambiguity.”

Body (part I) provides a graphic look at the sexual targeting during the genocide and the strenuous, heroic rescue efforts. Notable figures like Ruben Herian and Karen Jeppe, along with others, essentially sacrificed everything for these women. They established in-home orphanages and risked their lives to rescue them. The text also explores the ethical dilemmas faced during rescue missions, particularly when women were reluctant to leave their new Muslim families and become orphans again.

Skin (part II), is a contrast — it is a calm after the storm. The section takes us to the core of Semerdjian’s research. It offers an intriguing exploration of how tattoo culture was expressed through stories, photos, and personal accounts of women and their varied relationships with their markings.

Bones (part III) explores the phenomenon of pilgrimages to collect Armenian remains dispersed around the Deir ez-Zor desert in Syria. This was a reaction to the improper burials given during the genocide marches, during which many did not survive. The narrative also follows Semerdjian’s personal journey to Deir ez-Zor in the early 2000s for research and to explore her Syrian-Armenian roots.

Before the Syrian war, which devastated the Armenian communities and their “graves” in Deir ez-Zor, Armenians made arduous pilgrimages. They would drive up to 20 hours in a day to collect scattered human remains as a way to reconcile their uprooted history. For them, Deir ez-Zor was sacred yet haunted. Similar to how some wouldn’t spend a night in a graveyard, these pilgrims quickly gathered fragments of unclaimed bones in their pockets and left.

In the final chapters of Remnants, Semerdjian dissects what these pilgrimages reveal about memory culture and human nature’s relationship to mourning, particularly following genocide. The selection of Syria, specifically Aleppo, as one of the final settings in Remnants is both historically and symbolically significant. The current war in Syria has drastically compromised Aleppo’s Armenian community which has been one of the most important hubs for the diaspora, prompting broader discussions around cultural genocide, especially considering ongoing threats from Azerbaijan.

Throughout the book, we witness how incredible networks managed to orchestrate fundamental rescue missions and makeshift safe havens, accomplished without modern communication technology, proper infrastructure, or compensation. Throughout the book, we see the most innovative expressions of solidarity, survival, and hospitality that continue to resonate within Armenian communities today.

In her contribution to Armenian Genocide history, Semerdjian is candid with her readers about her professional and personal purpose. She transports us back in time while simultaneously engaging with contemporary perspectives. If one thing is to be taken from Remnants, it is the resilience of Armenian women who survived the unimaginable past while most of the world turned a blind eye. The book is not only a tribute to the tattooed women, but also to those who dedicated themselves to their rescue. As Semerdjian put it, “I would just hope that people walk away with a viewpoint that our community was extraordinarily kind. People opened their doors. You realize that there were a lot of people making great sacrifices.”

Book Reviews on

EVN Report

Can Armenia Be Independent?

In a voluminous collection of texts, historian and former diplomat Jirair Libaridian examines the reasons behind the moral, military and intellectual defeat of the Armenian elite in the context of three issues: the contemporary history of the Republic of Armenia, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and Armenian-Turkish relations.

Read moreThe Rise and Fall of the Hunchak Party

For the first time, a book in English traces the history of the Social Democrat Hunchak Party, which has been largely overlooked in Armenian historiography.

Read moreRe-reading Philip Marsden’s “The Crossing Place: A Journey Among the Armenians”

Philip Marsden’s “The Crossing Place: A Journey Among the Armenians” is atmospheric, gripping and revelatory. It delves into the seemingly exclusive club of a nation at the meeting point of cultures, writes Naneh Hovhannisyan.

Read moreWhen More is Less: Love and Cement in Revolutionary Yerevan

Christopher Atamian reviews “The Structure is Rotten, Comrade,” a new graphic novel by Viken Berberian and Yann Kebbi.

Read moreThe Eternal Magic of Mariam Petrosyan’s Gray House

Translated into several languages, Mariam Petrosyan’s epic novel “The Gray House” has enchanted readers across the world. In this first book review, Lilit Margaryan speaks with the elusive Petrosyan about her life and the life of a novel that took 18 years to write.

Read moreEVN Media Festival

The EVN Media Festival, in collaboration with Mirzoyan Library Foundation, will be bringing together photographers, editors, gallerists and different media organizations as part of the 2024 Media Festival Portfolio Review program. One-on-one sessions will help photographers articulate their voice and curate their visual language. The work presented for review will also be available for public viewing as part of an ad hoc exhibition for the duration of the day, linking talent to opportunity.

This book was tremendous. Very balanced and not filled with what can sometimes be considered emotional angst.