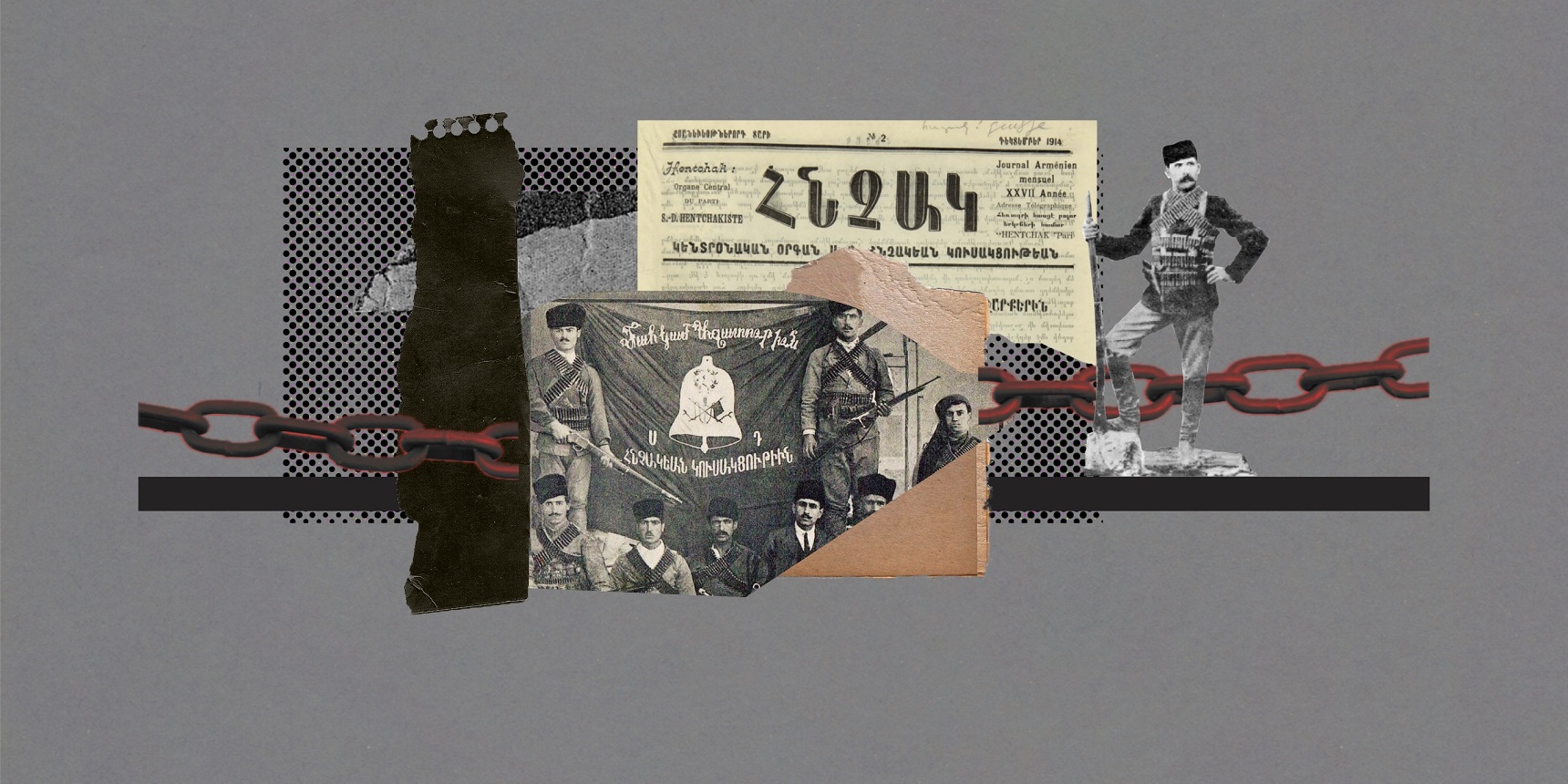

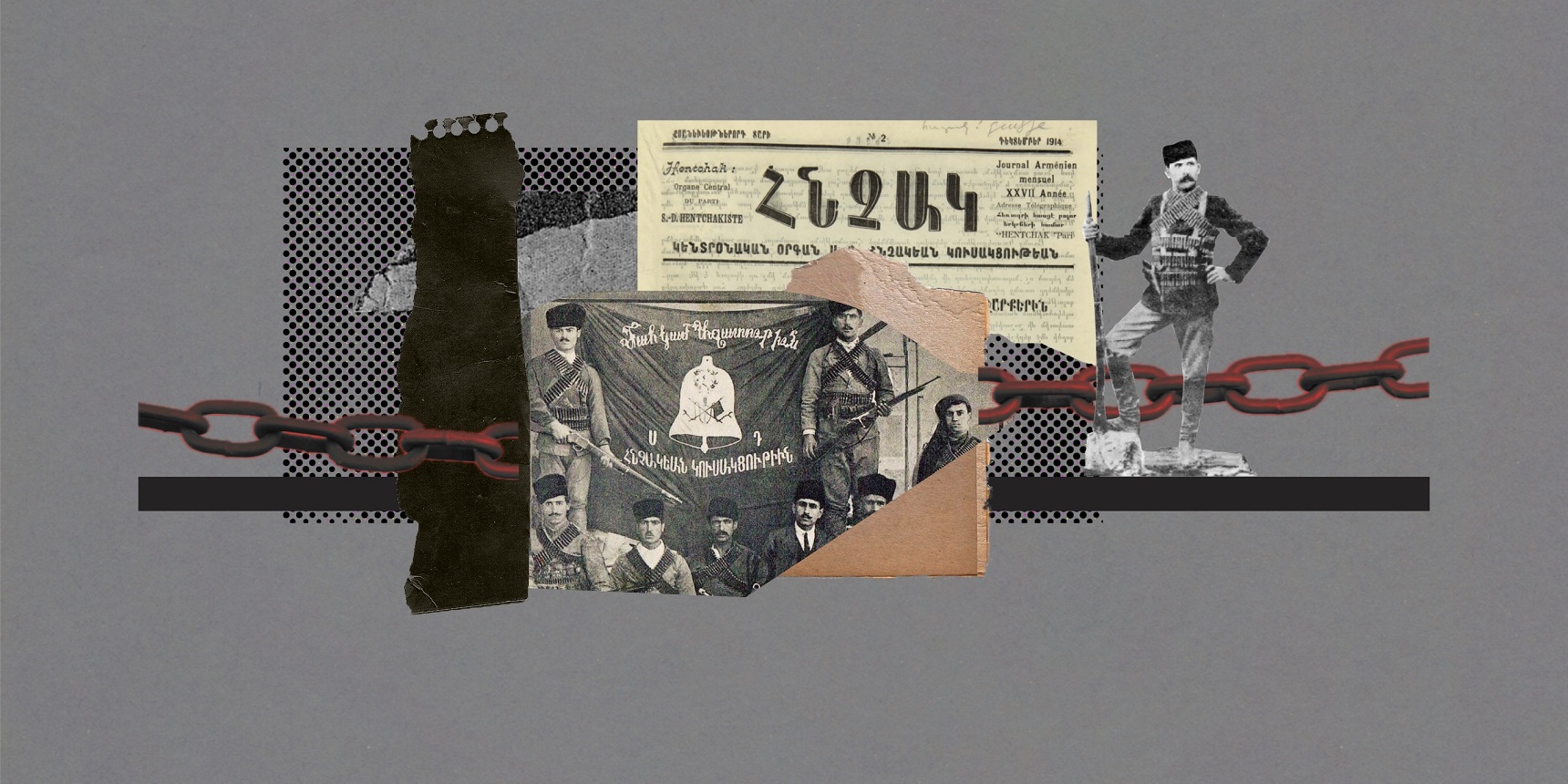

A large red flag flies from a deserted balcony on the second floor of a building on Abovyan Street in the heart of Yerevan. Few passers-by can identify the banner of the oldest Armenian political party still in operation, which has only a handful of active members remaining, both in the diaspora and in Armenia.

To address this lack of awareness and indifference, a collective work was recently published in English, “The Armenian Social Democrat Hunchakian Party: Politics, Ideology and Transnational History”.[1] The book brings together a variety of contributions that trace the unique history of this century-old party, and drawing on new research, sheds light on the history of the Hunchak Social Democrat Party, a major Armenian revolutionary party that operated in the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Persia and throughout the diaspora.

Between Marxism and Nationalism

Divided into several sections, the book covers the origins, ideology and regional history of the Hunchak party. It situates the party’s history within the debates surrounding socialism, populism and nationalism in the 19th and 20th centuries. The book reveals that the Hunchak party was not just an Armenian party, but also had an internationalist Marxist vision. The researchers in this volume draw on their expertise in a wide range of histories and languages, including Russian, Turkish, Persian and Spanish, to trace the emergence and role of this influential party. They explore its break with the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) Dashnaktsutyun, its experiences during the Armenian genocide, and its involvement in the formation of the first Armenian Republic and Soviet Armenia.

In 1887, a group of Armenian students from Russia convened in Geneva, a hotbed of revolutionaries within the Russian Empire. They were led by Avedis Nazarbekian, a Marxist student, and his companion Maro Vardanian, an activist and member of a Russian populist organization. This newly formed revolutionary group broke away from the moderate program of the Armenakan nationalist party, which was led by Mkrtich Portukalian, the editor-in-chief of the Marseille-based newspaper Armenia. Instead, they advocated for a unique combination of radical nationalism and internationalist Marxism mixed with Russian populism.

The Hunchak party stood out for its revolutionary activism. This is evident from its early military actions, such as the demonstration on July 27, 1890 in the KumKapi district of Istanbul, which aimed to draw the attention of European chancelleries to the plight of the Armenians. The party also led the Sasun rebellion of August 1894 against nomadic Kurdish tribes and Turkish tax collectors, the Zeïtun rebellion of 1895, attacks on the Armenian bourgeoisie and snitches employed by the Ottoman police.

Tumultuous Relations With ARF-Dashnaktsutyun

The Siamese twins of the Armenian revolutionary movement, Hunchaks and Dashnaks, have evolved along two parallel paths. The Hunchaks, who are anti-oligarchic but not anti-clerical, had a clear understanding of the objectives of the leaders of the Union and Progress Committee (CUP). Unlike their Dashnak comrades, they never trusted the Young Turks and avoided cooperating with them. The Hunchaks, who advocated for an autonomous Armenia, worked closely with other friendly Ottoman organizations. They showed solidarity with Greek, Arab, and Balkan nationalist parties, including Neguib Azouri, an influential figure in the Arab emancipation movement, who always included Armenian demands in his program.

The Hunchaks had reservations about the Young Turks’ coup in 1908, which restored the Ottoman constitution of 1876. Their concerns were further confirmed by the Adana massacres in 1909. During the 1913 party congress in Constanta, Romania, the Hunchak leaders pledged to fight the CUP, convinced of their genocidal intentions. They were unable to prevent the genocide, and their efforts were limited to a desperate self-defense in Cappadocia and Cilicia. Prominent Hunchak figures like Hampartsum Boyadjian (alias Murad of Bitlis) and Matteos Sarkissian (alias Paramaz) are remembered as heroes of the party and the nation.

Present in misfortune, the party played a notable role in helping Armenian refugees who were fleeing Cilicia. This was made possible by its well-established transnational network in the Americas. While the Hunchak party played a limited role in the establishment and political life of the first Republic of Armenia (1918-1920), which was governed by the ARF-Dashnaktsutyun, it demonstrated uncommon pragmatism and statesmanship by refraining from boycotting the Dashnak leaders’ efforts to rebuild the country. However, this unity would not withstand Sovietization and the creation of a Soviet Armenia, which the party saw as the fulfillment of its program formulated 38 years earlier.

Blindly loyal to Soviet Armenia, which it eventually merged into (both Avedis Nazarbekian and Maro Vardanian died in the Soviet Union as Communist Party members), and also loyal to the Holy See of Etchmiadzin over the Cilician See of Antelias, the Hunchak party established itself in the diaspora, with strong roots in Syria, Lebanon, Egypt and Argentina. But it was unable to withstand the wave of repatriation to the proletarian paradise of 1947. This paved the way for the ARF to gain influence in diaspora communities.

After the dark days of the Cold War, the Hunchak party united with the ARF and the Ramgavar party in Lebanon around the slogan of “positive neutrality” during the Lebanese civil war, and later in 1988, in opposition to the Armenian independence movement advocated by the Karabakh Committee. They were convinced that an independent Armenia could not live in peace alongside Turkey.

During the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, two Hunchak battalions (Paramaz and Jirayr Mourad) bravely participated in the fighting. But having missed the opportunity for independence and being too outdated to aspire to become a mass party, the Hunchak party was unable to modernize and adapt to the complex challenges of the young state, especially in a neoliberal and non-violent Armenia. Consequently, its decline is seen by some as inevitable.

What remains is the memory of those forgotten figures such as Paramaz and Stepan Sabah Gulian, the author of the great text of Armenian political thought, entitled “The Responsibles” [published between 1916 and 1974 in Armenian].

To avoid falling into the trap of folklore and victimization, the leaders of this century-old political party are faced with the responsibility of transforming themselves or stepping aside to allow young talent to develop a meaningful vision.

Footnote:

[1] Bedross Der Matossian (Editor) “The Armenian Social Democrat Hunchakian Party: Politics, Ideology and Transnational History”, I.B. Tauris, Londres, 296 pages.

Recently published

Aliyev Appears Open to Peace, Yet Prepares for Another Conflict

President Ilham Aliyev consistently delivered speeches full of hateful rhetoric directed at the Armenian people as the blockade of Artsakh was ongoing and even after the ethnic cleansing of the Armenians. Tatevik Hayrapetyan provides a compilation of some of Aliyev’s statements from the past year.

Read moreA Call for Political Transparency and Accountability

In a recent interview, Armenia’s Prime Minister made a number of revelatory remarks challenging Armenia’s long-standing narrative on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue. Davit Khachatryan takes a closer look.

Read moreWhat’s Next for Armenia’s Foreign and Security Policy? Part II

Since the restoration of its independence in 1991, Armenia has sought to maintain a balance of power in the region. However, maintaining this balance became challenging starting from the early years. Sossi Tatikyan presents an overview and analysis of Armenia’s foreign and security policies spanning three decades.

Read moreIran’s Experimental Policies in the South Caucasus

Relations between Azerbaijan and Iran deteriorated following the 2020 Artsakh War. Did the visit of Iran’s Foreign Minister to Baku in July 2023 succeed in resolving existing differences? Or should ongoing tensions between Baku and Tehran be anticipated?

Read more

One can argue that the worst legacy of the Armenian political parties was their continuation in the diaspora after the 1920 fall of the first Armenian Republic. They fragmented the diaspora for decades and could never realize their irrelevance as political entities in their respective host countries. Now compared that to the jewish diaspora which did not coalesce around multiple political identities but rather a religious and cultural one which kept them united for centuries. The result being that even after the formation of the state of Israel, no party was jockeying for power in the new republic and they supported the state of Israel as one voice which continues to this day. In contrast, the ARF tried to implement their decades old ideology in the 2nd republic of Armenia which further created a fragmented diaspora that could not become relevant in the new Armenian reality.

The ARF never seems to have gotten over their loss of power in 1920 in Armenia and has acted as if it is a “government in exile” since then. It got its wish to get back into government by being a junior partner to the Kocharyan and Sargsyan regimes from 1998 to 2018. How did that work out ? The economic, diplomatic and military decline of Armenia occurred mainly during that period. When the ARF speaks today against Pashinyan, it is not clear what is their motivation; getting back into power or genuine concern about the state of Armenia? There is a conflict of interest which causes needless divisions. I agree that there should be no political parties outside Armenia. Instead the focus should be on the survival and building up of a quasi religious and cultural entity called the Armenian nation which has a strong sense of its identity rooted in its language and history. I am not absolving nor defending the Pashinyan government from its own mistakes and misrule, but at least they are subject to an (imperfect) democratic process. If the people don’t agree , they can be voted out. The government and diaspora should be working closely together to defend Armenia in its time of existential peril.