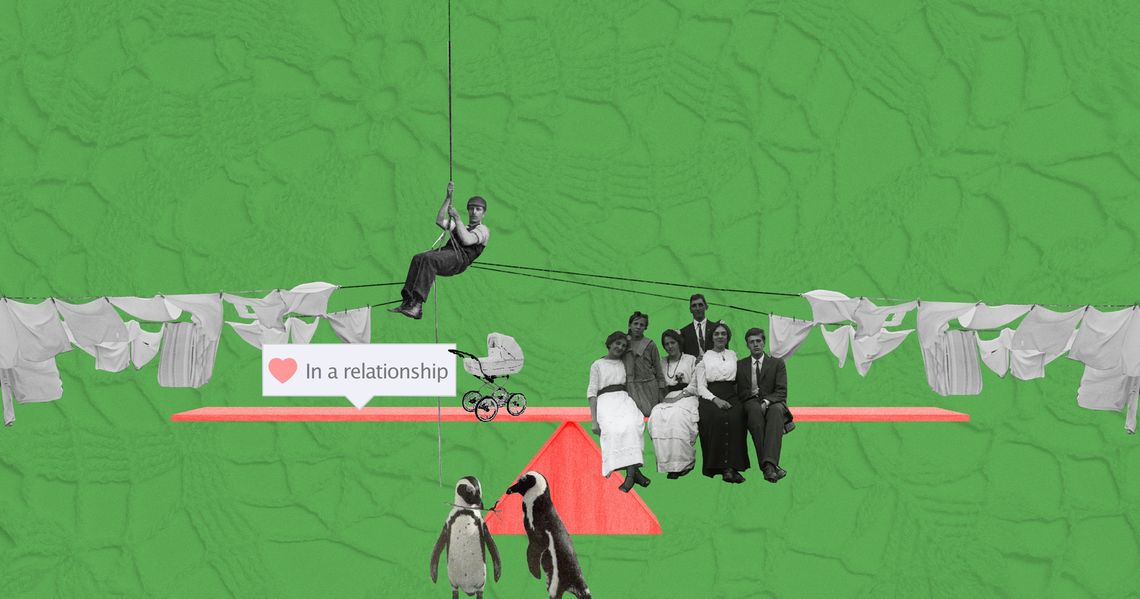

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

When Armenians think of a wedding, probably the first thing that comes to mind is the backdrop of a church. The Armenian Apostolic Church carries a special status in Armenia’s Constitution. However, it may be surprising to learn that the process to “register” a wedding, i.e. to have the marriage legally recognized by the State, is completely separate from the church ceremony. In American movies, you might hear a priest say, “By the power vested in me… I now pronounce you man and wife.” In Armenia, there is no such power vested in priests. Likely a legacy of Armenia’s atheist Soviet past, only a civil servant can legally register a marriage, a process known in Armenian as zags (though the term is originally a Russian abbreviation for “civil registration”). For a number of different reasons, couples may never follow through with the civil registration after having their religious ceremony. Under Armenian Family Law, however, such unions are not legally recognized, and that can lead to a lot of headaches down the road. In some cases, it can even curtail basic human rights.

With changes in modern perceptions of the institution of the family, the public discourse on the traditional Armenian family, the protection and perpetuation of the family institution, increasing the role of women in society and consequently the status of women in the family, and changes in perceptions regarding children’s rights, a number of issues have arisen in Family Law that need clarification. What changes are families experiencing in the modern era? How are these changes reflected in family legal relations? What new legal regulations are emerging in international and domestic legislation that contribute to the modernization of the family institution?

The Historical Perspective

A brief historical overview and analysis of the modern legal field can help form an understanding of some of the issues and challenges that the modern family and Family Law face.

Reflecting on the concept of family and the developmental phases of that institution, let us point out that scientific thought has always been focused on observations of the phases of family and marital relationships. From the Ancient World to the present day, the family institution has been studied by anthropologists, sociologists, historians and legal scholars.

According to historian Johann Jacob Bachofen,[1] and subsequently anthropologist and social theorist Lewis Henry Morgan,[2] the “family institution” has gone through the following phases of development:

- Consanguine family (free relations between relatives)

- Inter-tribal marriages involving group relationships, in which only one parent was known for certain—the mother. This was the period of matriarchy.

- Marriage between couples, but without cohabitation, in open relationships and with volitional duration.

- A patriarchal family, where the male position was dominant, including the marriage of one man with several women.

- And finally the monogamous family—the marriage of a single couple with a long-term relationship.

In his work “The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State”, Friedrich Engels (who co-authored The Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx) describes the evolution of the “family institute”, dividing it into three main stages:

- Savagery—group marriage

- Barbarism—pairing marriage

- Civilization—monogamous marriage

According to Engels, the monogamous marriage was the first form of the family to be based not on natural but on economic conditions—on the victory of private property over spontaneously-formed communal property. The husband dominated the family, and the children’s parentage was (theoretically) confirmed.

Philosophical, legal and sociological thought has also tried to formulate the essence of marriage. An in-depth approach to the issue is conditioned by how marriage is perceived, and thus which branch of law Family Law belongs to.

Unlike post-Soviet countries, Western European countries consider Family Law as a sub-branch of Civil Law. This approach is conditioned by the fact that, in Western European countries, marriage is considered a civil-legal transaction—the same as a contract—between a man and a woman. The direction in which Family Law in the Republic of Armenia will develop is conditioned by the perception of the essence of marriage. Scholarly circles recognize three concepts regarding Family Law:

- Marriage as a sacrament

- Marriage as a contract

- Marriage as a special institution

Marriage as a Sacrament

Marriage was considered a sacrament during the era of religious law. Family relations were under the jurisdiction of the church, and marriage had a spiritual divine sacrament. Medieval Armenian jurisprudential thought also considered marriage to be a divine institution. It was regulated by canon law, as well as by Mkhitar Gosh’s Lawcode (Datastanagirk). According to Armenian law, the necessary conditions for marriage were:

- Monogamy

- Marital maturity

- Mutual marital consent

- Parental consent

- No close blood relationship

- Belonging to the same faith

Spouses also assumed mutual rights and responsibilities, such as respect, loyalty, not spreading gossip about each other, and running the home together. There was a division of labor within the family.

In case of divorce, the man had the right to divorce the woman on three grounds:

1. Her infidelity

2. Leprosy, spotting, being possessed, scurvy

3. Witchcraft and sometimes in cases of infertility

The woman had the right to divorce her husband on six grounds, in cases of:

1. Infidelity

2. Wizardry

3. Impotence

4. Bestiality

5. Violence against the wife

6. Robbery

Thus, violence against women has clearly been condemned in Armenian Family Law and has long since been a basis for divorce.

Marriage as a Contract

Marriage as a contractual approach originated in Ancient Rome. In Roman law, all forms of marriage were considered civil transactions. The concept of the marriage contract gained new momentum when the civil act of marriage was separated from religious law, and the norms of civil law began to apply to marital relationships.

The French Constitution of 1791 established that marriage was a civil transaction, after which this approach was incorporated into the French Civil Code. Marriage came to be regarded as a civil contract and was enshrined in the civil concepts of a number of European countries.

Marriage as a Special Institution

Proponents of the “marriage is a special institution” theory see contractual elements in marriage, but refuse to accept it as merely a contract. According to this, marriage is a status, not an obligation nor an ordinary property contract; it is an agreement to enter into a special type of relationship. Thus, in the modern legal understanding of Armenia, marriage is considered not a sub-branch of Civil Law, but a type of family-legal contract. One of the main principles of current family legislation in the Republic of Armenia is that only marriages registered in civil registry offices are legally recognized. Only a marriage registered in strict accordance with the law creates rights and obligations foreseen by law for the spouses. However, “de-facto marriages” (pastatsi in Armenian, where a religious ceremony was held but never registered with the State) are not uncommon in Armenia. They are especially relevant from the viewpoint of Armenian Family Law and the perspectives that form the basis for the development and improvement of family legislation. At first glance, legislative regulation of these issues is not easy, but it is inevitable. The issue of legal protection of de-facto marriage and partnerships remains unresolved by the Family Code, especially in the domain of domestic violence, as women’s rights are often the ones that are violated. In marriages not registered in accordance with the law, women are often deprived of property and other rights—which has the characteristics of economic violence—as well as subjected to other forms of domestic violence—psychological, sexual and physical. Armenia does not recognize the equivalent of a “common law” marriage that was never legally registered.

Of course, the sphere of family relations is one of those sensitive areas, where the extremely delicate aspects of personal life are most touched upon, where the personal prevails over property, and their content is shrouded in the moral perceptions that prevail in society. The driving forces for the development of these relations are the interconnected interests of the individual, society and the state, which is why a balanced combination of public and private principles is required in regulating them. From this point of view, the state’s manifestation of legal indifference to de-facto marriages allows for certain restrictions, and in some cases violations, of women’s and children’s rights. In order to avoid these challenges, it is necessary to provide legal protection through legislation.

—————–

[1] Bachofen, J.J. ′Mother Right′. Vols. 1-5. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 2003-2008.

[2] Morgan, L.G. Ancient Society, 1877.

Who Benefits From Comfortable Workplace Environments for Mothers and Babies?

Having a designated nursing room at the workplace and flexible working conditions help working mothers to continue breastfeeding after returning to work, keeping the emotional bond between mother and baby uninterrupted․

Read moreMarriage Law and Culture: Ottoman Armenians and Women’s Efforts for Reform

Although Armenian women did not directly participate in the public discourse on the family structure and institution of marriage during the 19th to early 20th centuries in the Ottoman Empire, they articulated their concerns against gender inequalities through the voices of the fictional characters they created in their writings.

Read moreSee What’s New

House of Horror

In this “True But Not Real Story” the Verdyans are unperturbed that the house they are buying is known to be possessed by ghosts and evil spirits.

Read moreBaku Threatens Yerevan With “Peace Treaty”

Developments after the 2020 Artsakh War reveal that Azerbaijan has no intention to work toward regional peace and stability. Together with Turkey, Baku aims to change the regional structure at the expense of Armenia’s security interests and needs.

Read moreThe Aliyev Regime’s Frustration and Hubris

The Aliyev regime is profoundly frustrated, writes Nerses Kopalyan, however, this frustration is an inherent byproduct of Baku’s illusions of grandeur and the awkward hubris that has consumed Ilham Aliyev.

Read more