Listen to the article.

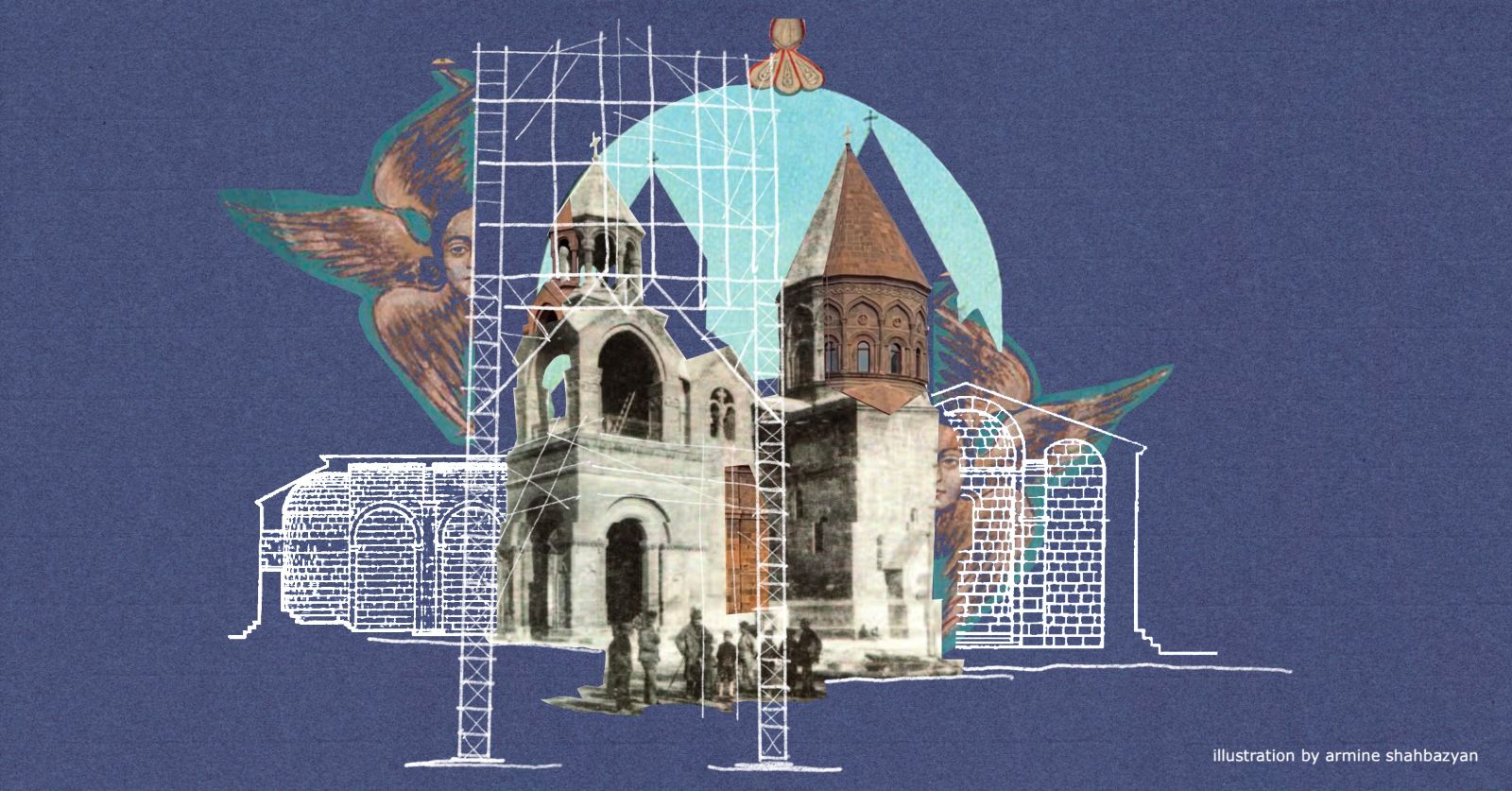

After almost seven years of intensive restoration, the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, considered to be the oldest cathedral in the world, was reconsecrated and finally opened its doors to the faithful last September.

The seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church is considered one of the exceptional monuments of universal significance, and is included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. According to tradition, Saint Gregory the Illuminator had a vision in which Christ descended from heaven and indicated the site where the cathedral should be built. Following this vision, Gregory, together with King Trdat III, founded the Etchmiadzin Cathedral in 303 AD, shortly after the adoption of Christianity as the state religion in 301 AD. While the cathedral has undergone various renovations over the centuries, the most extensive restoration took place in the 1620s under the leadership of Catholicos Movses of Tatev. The structure that stands today largely reflects that 17th-century reconstruction.

Amiran Badishyan, the chief architect overseeing the restoration of the Mother Cathedral, recalls that there were initially no plans for a full-scale renovation. His Holiness Catholicos Karekin II had simply instructed specialists to remove vegetation growing on the cathedral’s roof. What began as a routine maintenance task, however, soon uncovered much deeper structural issues.

“It became clear that the entire structure—inside and out, from the foundations to the cross atop the dome, from the eastern bell tower to the western—required serious reinforcement and restoration,” says Badishyan. He remembers that in 2015, while the interior walls were being cleaned in preparation for the Pope’s visit, they discovered dangerous cracks hidden beneath the murals.

“In fact, it all began in 2012,” he explains, “when, at the Catholicos’s instruction, we were to carry out minor cosmetic repairs to the roof areas, where vegetation had overgrown. There was even an apricot tree sprouting from the dome of one of the bell towers. That’s when I realized the roofs needed complete renovation.”

According to Badishyan, the restoration project of the Mother Cathedral was approved by both the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports and UNESCO. The extensive undertaking, which spanned 12 years, was carried out in two key phases: the first focused on research, analysis and planning; the second on the actual construction and restoration work.

The research phase brought together some of Armenia’s leading experts, including architects, engineers, material scientists and stone specialists, and also involved an assessment by the country’s National Seismic Protection Service. Their investigations uncovered numerous issues related to the physical condition of the cathedral, many of which had remained hidden for decades.

Reflecting on the cathedral’s previous condition, Badishyan explains that during their investigations, they uncovered what he describes as a “bandage” of murals and plaster covering a fractured structural framework; damage that was not visible from below.

“In one section, after we removed the mural and then the layer of plaster from the arch, a large stone simply fell to the ground,” he recalls. “It had been held in place solely by the plaster. Later, we found similar instances elsewhere, which posed serious structural risks.”

Experts determined that the main materials needed for the restoration had to be imported from Italy. Restoration protocols require that new materials be compatible with the originals; for instance, if a historic wall was built using stone and lime mortar, then the restoration must also use lime-based binding materials. However, such materials are not available in Armenia, or in many other countries, necessitating their import from Italy. Additional essential restoration materials were also sourced from there.

Despite the absence of certain materials locally, Badishyan emphasizes that Armenia has significant restoration capacity, spanning the full process, from research and design to hands-on execution.

The cross atop the cathedral’s dome was replaced with a new bronze replica, identical in style and dimensions to the original. According to Badishyan, the previous cross, installed in the 17th century, was constructed from thin brass plates and had severely deteriorated over time. It has since been preserved and is now displayed in the cathedral’s museum.

“None of this work was easy; we were working with a 1700-year-old temple,” Badishyan reflects. He describes the project as an unprecedented achievement in Armenia’s restoration history, and states confidently that, barring extraordinary circumstances, the cathedral has been reinforced so thoroughly that it may well endure for eternity.

The Legacy of Four Generations of Hovnatanyans

The cathedral of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin is also renowned for its rich collection of murals, created by some of the most prominent Armenian painters of their time. Among them were four generations of the Hovnatanyan family, whose contributions helped elevate Armenian fine art to a new level. Preserving their work was a key priority during the recent restoration.

In the 1710s, the celebrated artist Naghash Hovnatanyan (Hovnatan) was invited to Etchmiadzin to adorn the cathedral’s interior. He was later joined by his sons, Hakob and Harutyun Hovnatanyan, who worked alongside him to depict sacred figures, including Saints Gayane and Hripsime. In 1778, Hakob’s son, Hovnatan, continued the family legacy by restoring and enriching the murals painted by his distinguished grandfather.

The fourth-generation artist, Mkrtum Hovnatanyan, Hakob’s grandson, was a gifted portraitist. A series of his portraits of Armenian kings are preserved in the Pontifical Residence of the Mother See. He also decorated the main hall of the residence, leaving a lasting mark on the spiritual and artistic heritage of the site.

Bishop Mushegh Babayan, Director of the Administrative and Economic Department of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, notes that following the restoration, the cathedral’s colors have regained their original brilliance, closely resembling the hues originally applied by the Hovnatanyan muralists.

“This beauty had long been hidden beneath layers of soot and candle smoke accumulated over centuries. It has now been revealed thanks to the expertise of our restoration masters,” the bishop says.

As part of the restoration, specialists from the Mural Restoration Research Center had to carefully remove sections of the 18th-century murals to assess their condition and ensure their preservation.

“To avoid damaging the artwork, it was decided to dismantle the murals in areas where structural reinforcement was necessary, specifically around the four main columns and 12 arches of the cathedral,” explains Arzhanik Hovhannisyan, the project’s lead mural restoration specialist. “After meticulous restoration, the murals were returned to their original locations.”

In total, the cathedral’s murals cover an area of 2,400 square meters. Approximately 630 square meters were carefully removed, restored, and reinstalled. An additional 60 square meters, comprising 123 mural fragments, were archived for conservation.

“It’s an unprecedented undertaking in terms of scale,” says Hovhannisyan. “While the technique is internationally recognized, it’s not something that can be implemented just anywhere. We underwent specialized training to carry it out.”

During the dismantling process, the team also uncovered mural fragments that predate the Hovnatanyan period.

“Earlier layers of murals emerged from beneath certain sections,” Hovhannisyan explains. “However, we couldn’t reinstall them in their original places, as doing so might have disrupted the overall visual harmony. These fragments will instead be exhibited in the museum.”

To preserve the restored murals, a new ventilation system was installed, which specialists hope will protect the interior from humidity. Smoke and soot will also no longer pose a threat as an adjacent hall is being constructed where visitors can light candles, keeping the interior atmosphere stable.

The restoration was carried out without any state funding. A nationwide fundraising campaign had initially been planned, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 Artsakh War, Catholicos Karekin II decided against it. Instead, the project was made possible through the generous contributions of around ten principal benefactors. In recognition of their support, the Catholicos awarded them the high distinction of the “Holy Etchmiadzin” Order of the Armenian Apostolic Church, as well as the honorary title “Daughter of Holy Etchmiadzin” and the Patriarchal Order.

Holy Chrism: A Seal of Identity

On the eve of the Mother Cathedral’s reopening, the scent of newly prepared holy chrism (myrrh) once again filled the air from the Open Altar of Saint Trdat. The mixture, prepared in a 180-liter silver cauldron, included olive oil, balsam, extracts from more than 40 fragrant flowers and incenses, aromatic roots, chrism blessed in Antelias, and remnants of previously consecrated chrism. The process was accompanied by traditional prayers and blessings.

While several cauldrons are preserved at the Mother See, the one used for this preparation, a silver vessel made in Moscow, has been in service since 1895. It was donated to Holy Etchmiadzin by Nor Nakhichevan merchant Agha Gaspar Harutyunyan Karapetoghyan. The first chrism prepared in it was blessed by Catholicos Khrimyan Hayrik that same year.

The Armenian Catholicos blesses the chrism using three sacred relics of the Church: the Holy Cross, the Holy Lance, and the Right Hand of Saint Gregory the Illuminator.

Only the Catholicos of All Armenians holds the authority to bless the holy chrism, a sacred ritual that takes place roughly every five to seven years. With the latest ceremony in 2024, Catholicos Karekin II has now presided over four such blessings. This most recent one came after a nine-year hiatus—delayed first by the 2020 Artsakh War and later by the fall of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023 and the forced displacement of its Armenian population.

Since Armenia’s independence, the tradition of assigning symbolic names to each chrism blessing has taken root. The 1991 ceremony was dubbed the “Independence Chrism,” followed by the “Renaissance Chrism” in 1996, the “1700th Anniversary Chrism” in 2001, and the “Victory Chrism” in 2015. The 2024 blessing and the subsequent reconsecration of the Mother Cathedral both carry the theme: “Seal of Identity.”

During the chrism blessing, Catholicos Karekin II once again urged the international community and sister churches to take concrete steps against Azerbaijan’s expansionist policies and growing demands. He called for the return of seized Armenian border territories, the protection of the rights of forcibly displaced Artsakh Armenians, the release of Armenian captives, and the preservation of Artsakh’s endangered Armenian cultural and spiritual heritage.

Following the ceremony, the Catholicos distributed pitchers and vials of the newly consecrated chrism to diocesan leaders. Upon their return to their respective communities, they will use it to bless water and distribute the sacred oil to the faithful across the country, allowing Armenians everywhere to partake in this rare and deeply symbolic event.

Also see

Rethinking Monument Preservation in Armenia

Armenia is developing policies to inventory, preserve, restore and promote historical monuments, recognizing their economic and cultural value. While progress aligns with sustainable development goals, significant challenges in preservation and management persist.

Read moreAppropriation of Armenian Cultural Heritage of Artsakh

The 2020 war and 2023 military operations in Artsakh have left Armenian cultural heritage vulnerable to destruction and appropriation. Azerbaijan's reclassification of Armenian sites aims to erase Armenian identity, falsify history, and legitimize territorial claims through cultural expropriation.

Read moreDestruction of Armenian Cultural Heritage of Artsakh

Azerbaijan’s systematic destruction of Artsakh's cultural heritage not only erases the unique collective identity of its people but also deals a significant blow to the entire world, destabilizing present and future prospects for peace and security in the South Caucasus.

Read moreArts & Culture

The Power and Politics of Yerevan’s Statues

Yerevan’s statues reveal shifting political ideologies and national identity, from Soviet heroes to national figures, international allies and “symbolic” women. Hovhannes Nazaretyan explores how public monuments reflect power, memory and Armenia’s evolving historical and geopolitical narratives.

Read moreDreams Against Empire: Parajanov’s Cinematic Defiance

In this poetic exploration of filmmaker Sergey Parajanov’s radical defiance against Soviet conformity, Ani Poghosyan traces how his visionary cinema, rooted in Armenian identity and artistic freedom, challenged empire, celebrated cultural memory, and outlived the system that sought to silence him.

Read morePınar Selek’s Intellectual Journey of Resistance

Taline Oundjian traces the intellectual and political journey of Pınar Selek, a Turkish feminist and anti-militarist persecuted by the state, whose work on structural violence, memory, and the Armenian genocide offers powerful insights into resistance, identity and forgotten histories.

Read more